A CELEBRATION OF SYDNEY SCHOOL’S ARCHITECTURE IN THE HEART OF BANGKOK, ART4D’S FIRST ARCHITECTURE REVISIT EXPLORES BANGKOK’S AUSTRALIAN EMBASSY WHICH HAS BEEN IN SERVICE FOR MORE THAN 40 YEARS, BEFORE MOVING TO ITS NEW LOCATION.

During the 1960s, the Australian architectural community saw the birth of a new movement of young generation architects known as the ‘Sydney School.’ It has been said that the word originates from a traveling exhibition that circulated a good number of museums in Australia named ‘15 Houses by Sydney Architect’ (1961) that had Bruce Robertson as its curator. It’s not an easy task to specifically explain what ‘Sydney School’ really is but there is a number of architectural academics who have tried to describe certain common natures of this group of architects, from the use of design language that is not only universal but also follows the concept of modern architecture to the great consideration given to the site’s climatic conditions and contexts and people’s ways of life as well as the use of local materials. It also shies away from the nationalistic architecture and the use of built structures to express nationalist values with a straightforward use of conventional architectural attributes. The concept had driven the movement to rise as one of the most recognized architectural styles of Modern Australian Architecture in the latter half of the 20th Century.

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

AUSTRALIA WAS ONE OF THE COUNTRIES WHOSE ADOPTION OF ‘NEW BRUTALISM’ HAD BECOME THE KEY ELEMENT

Ken Woolley (1933-2015) is one of the key figures of the ‘Sydney School’ movement. After graduating in architecture from the University of Sydney in 1955, his outstanding academic performance earned him a scholarship from the university. With this scholarship, Woolley traveled overseas and was exposed to the architecture of different worlds. In 1956, he secured a position at Chamberlin Powell and Bon in England (which was working on some highly interesting projects such as the Barbican Estate). It was there that he became more interested in and engaged with the ‘New Brutalism.’ The tenet was becoming highly interested in the young generation architects of the time with its role as one of the conceptual foundations of works from the Post-War Architecture era. More importantly, before the movement made its way to other parts of the world, Australia was one of the countries whose adoption of ‘New Brutalism’ had become the key element leading to the ramification of the idea that eventually gave birth to idiosyncratic movements such as the ‘Sydney School.’

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

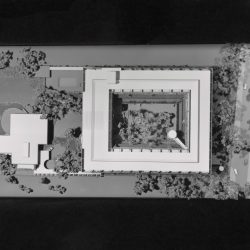

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo courtesy of Weerapol Singnoi

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

After gaining his professional experience in England, Woolley returned home to Australia where he co-founded the architecture firm, Ancher, Mortlock and Woolley. He began working on architectural projects from the 1960s on and his works and company gradually garnered recognition and reputation. In 1973, the Australian Government assigned Woolley the task of designing the Australian Embassy building (1973-1978) in Bangkok with revered Thai architect, M.L. Tridhosyuth Devakul serving as the consultant.

From the point of view of the project’s consultant, M.L. Tridhosyuth recalled the collaboration with Woolley describing that, “stylistically, the building was conceived from a design concept that aims to express the identity and elements of Thai Architecture.” He invited Woolley to see Suan Pakkad Palace’s unique architecture that includes the architectural program where the ground floor is surrounded by the waterway of the garden pond. After collecting all the needed information, the two began the development of the design together back in Sydney. The finalized design was, therefore, conceived from the amalgamation of the two cultures, consequentially materializing into the shape and form of a building with an elevated floor surrounded by a connected waterway reminiscent of Bangkok’s waterways. In the meantime, the built geographical condition accentuates the presence of the architecture as an island surrounded by an aquatic mass, similar to the continent of Australia.

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

THE FLOORPLAN BEARS A FUNCTIONAL SPACE THAT EXTENDS IN PHYSICAL CORRESPONDENCE WITH THE ASCENDING HEIGHT OF THE ARCHITECTURAL MASS

If we were to consider the Australian Embassy building with Sydney School’s architectural style, what the embassy’s architecture reflects are all the distinctive architectural features found in works coming out of the movement. Some examples include the creation of a new environment that corresponds with the work’s physical and cultural contexts. Ken Woolley decided to use a large pond to connect all the spaces, from the chancery and main office space to the massive garden. The consideration for the climatic conditions of the site resulted in the design of the south-facing large sun protection panel. The floor plan bears a functional space that extends in physical correspondence with the ascending height of the architectural mass. What the design offers are more shaded areas and the exterior, which is protected from the heat of the sun. The freestanding columns are reminiscent of the key characteristics of traditional Thailand while the enclosed floor plan resulted in the conception of a large open-air courtyard. The area at the center grants greater heat ventilation and allows for the presence of natural light. The use of locally available materials such as the yellow ceramic tiles, which bear similar details to the ceramic roof tiles used in the construction of the roof, as the exterior shell renders a distinctive appearance to the building. With the universality of the work’s architectural language, many elements of the building remind us of Woolley’s design language. The use of freestanding columns and details of extended eaves that help to protect the exterior shell from the heat recall the architecture of Petit & Sevitt House (1962-1978) and its sloped program with the presence of trees around the courtyard’s walkway. The area at the center is an element that can be found in projects such as The Penthouse (1965-1968) while the emphasis of the core of the cylindrical stairway, the partially undulating walks and concrete sun-protection panels as well as extended floor that corresponds with the height of each story and use of local tiles are reminders of Wentworth Student Union Building, Sydney University (1968-1972).

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

In 2014, one year before Woolley passed away, he gave an interview about sustainability and how the concept was far from new, especially with the comparative interpretation with the preexisting concept of New Brutalism. The notion didn’t interest him much for Woolley believed that if all the variations are straightforwardly and truthfully treated, the work would be, in itself, sensible, and to him, that is sustainability.

From the day of its first operation in 1979 to the day when the building reached its 38th birthday, the surrounding context has changed from unoccupied pieces of land to a highly urbanized area with high-rise buildings constructed around the embassy’s perimeter. Like most buildings, there comes a time to assess how a structure best serves the operations and people it houses, and sadly after considering the current and future needs of the Australian Embassy’s work, a decision to re-build the chancery at Wireless Road was made. The new chancery is planned to be up and running in a couple of months. The year 2017 will bid farewell to the iconic Australian Embassy building before the land will be sold with new possibilities for new developments to take place in the future.

If Woolley’s embassy building was conceived from his perception and interpretation of the site’s surrounding context, its departure that has time and changes as its cause seems reasonable in its own way. Perhaps it is like what Ken Woolley once said, ‘if it’s sensible, it’s likely to be sustainable.’

* The years in the brackets refer to the starting and completion dates of the project.

Australian Embassy, Bangkok, Photo courtesy of Weerapol Singnoi

TEXT: WICHIT HORYINGSAWAD

www.kenwoolley.com.au