OBSERVATION AND NEGOTIATION AT THE CULTURAL SHORELINE. A SHIFTING APPROACH TOWARD DESIGN AND PRESERVATION IN RAPIDLY CHANGING HO CHI MINH CITY, art4d TALKS WITH HTA + PIZZINI ARCHITECTS.

We would like to ask you first about your relationship with the city.

HOANH TRAN: I was born in Saigon and I left Vietnam at the end of the war so I lived in America most of my life. I came back to Saigon almost 20 years ago so I have been practicing in Saigon for almost two decades.

ARCHIE PIZZINI: I grew up in America, I am from Texas and my ancestors came from Mexico. I have known Hoanh for a long time. I came here about 10 years ago at the time the current office was formed.

In Situ, The City, Image © Archie Pizzini

Let’s talk about the exhibition ‘In Situ.’ We’ve read that it was part of your PHD dissertation defense? Congratulations.

AP: Yes. Thank you. While we did do two separate PHDs, the exhibition was a PHD exhibition for both of us. A lot of it was the photos I have been taking since I arrived here in 2005. I started taking them because here was so different from America and it was just so interesting, so exciting, so dense and so alive. Through the PHD process I began to understand more and more that it has a lot to do with the scale of the city and the scale at which things happen.

In Situ, The City, Image © Archie Pizzini

HT: Perhaps the show could be understood simply this way, Archie’s photographs on the wall are basically his observations of the city. It is the current Saigon with all of the daily life being acted out and captured by his camera. The installation is a collaboration between Archie and myself. We showed the layers of Ho Chi Minh City through time, through history, through all of the events that happened in the last few hundred years in the city. Conceptually, it is about how we see our city and the way that mostly I see the city.

In Situ exhibition, Image © Archie Pizzini

HT: This city is really viewed best when you look at it as an accumulation. An accumulation of all of the layers. 300 years old is really not that old, and the physical remains of the city are actually only 150 to 180 years old, but you still can see the physical layers, the cultural layers, and all sorts of other layers on top of each other. Coincidentally the show was done inside this gallery space, which we designed, which works out really well for us because the focus of the gallery is to make people observe, right? As architects we push people to look at the city by emphasizing these windows looking out the back and the front to the city. Then the photographs on the wall are that city, so it is all connected.

Galerie Quynh Entry, Image © Archie Pizzini

Galerie Quynh Courtyard View, Image © Archie Pizzini

AP: For me, sociologically when I look at the city, I see a sort of a dichotomy in the world between two different cultures. I see a globalizing culture, which is very much about large scale, about corporations and about control, and I see a small scale which is still the old school, individual-based Vietnam. It could be summed up in the statistic (by the World Bank) that in 2011, 65.4% of Vietnam’s population that was employed was self-employed, and for the same year in America, it was 6.8%. So it is a difference in scale and it is supported by a difference in the scale of the architecture.

You see an old building like this one that we’re in, and you see all these little itty-bitty bite-sized chunks that could be taken over by a local person and when you go to a large mall it is all corporations, it has to be. There is this sort of thing and I call it, in my PHD, a cultural shoreline. You see a lot of very large corporations across the street while here in the back you see the small scale and right in the middle of both is this contemporary art space, this is where contemporary art is supposed to illuminate, to make sense of, to interpret the situation. This cultural confrontation may be one of the most important conditions in the world today.

In Situ, Ca Phe May Bay, Image © Archie Pizzini

HT: What we were trying to do was to show two different ways to look at cities, one is from the sidewalk and one is from an airplane. I think a healthy way to look at cities utilizes both ways. If you look only from the sidewalk, you might miss something but if you are only looking from the airplane you miss a lot because of the details you cannot see. We see a lot of the big master plans being made in countries that have a very globalized lifestyle. And perhaps the people who are actually designing the city assume that the lifestyle is going to be exactly like their lifestyle and in reality it couldn’t be more different. A lot of it has to do with the need to observe before you design and I think that need is neglected a lot because there are certain assumptions made.

AP: And what you find out when you observe all of this is that the sociological texture of the city, which is very small scale, the economic texture, which is very small scale and the urban texture which is very small scale, all support each other and are all enmeshed, you destroy one and you destroy them all.

In Situ, Ca Phe May Bay, Image © Archie Pizzini

In 2008 you talked in your lecture about the people’s lifestyle attitude that tends to be influenced by marketing. That was 7-8 years ago. How do you see the change since then?

AP: My feeling is that change is happening very fast but there is also a rush to change happening as well. Our main point was made with our opening statement: “Vietnam already works.” When I arrived here I felt like most of the young architects that worked for us had a feeling that their country was somehow not working and not up to speed and needed to be improved by the West. But what was fruitful was this understanding that Vietnam was already working, it was just working in a way that perhaps people don’t understand and perhaps people don’t give Vietnam credit for.

And it is efficient in a lot of ways that surpass that of the West. So that was our main realization and that has been building up to the PHD where I gathered more information and more understanding about the underlying systems. For example, there is a system for collecting newspapers off of transpacific flights. These newspapers will be re-sold and not really in an organized manner. This is not some giant organization, this was people who were grabbing discarded things and saying “I can do something with this” and somebody else was like “Oh I will take it and I can do that.” Or If you look around you will see people driving around with these big blue barrels strapped to the backs of motorcycles and what they are doing is that they are collecting uneaten soup, soup from the noodle shops, and they take that and they use it to feed the pigs. This sort of thing is what I’m talking about.

Hoanh and Archie’s office, Image © Archie Pizzini

AP: You see that nobody made the decision to do these things – let’s figure out a way for Vietnam to recycle soup, no – it just happened. It was probably more like, “Don’t throw that soup away, I can do something with it!” and then this system gathered. The thing about Vietnam is that the whole texture is so small scale that it supports these small-scale interventions. When you get into another place like the place where I came from, it is harder to be small scale. Even in architectural practice. For instance, I had been working for large corporations in America and there were all these standardized windows you had to work with because if you didn’t you were going to blow the budget. Then I got here and we were laying out some building and I asked Hoanh, “How big are windows here?” and he said, “Any size you want.” And I thought, “Yes! I am in the right place!”

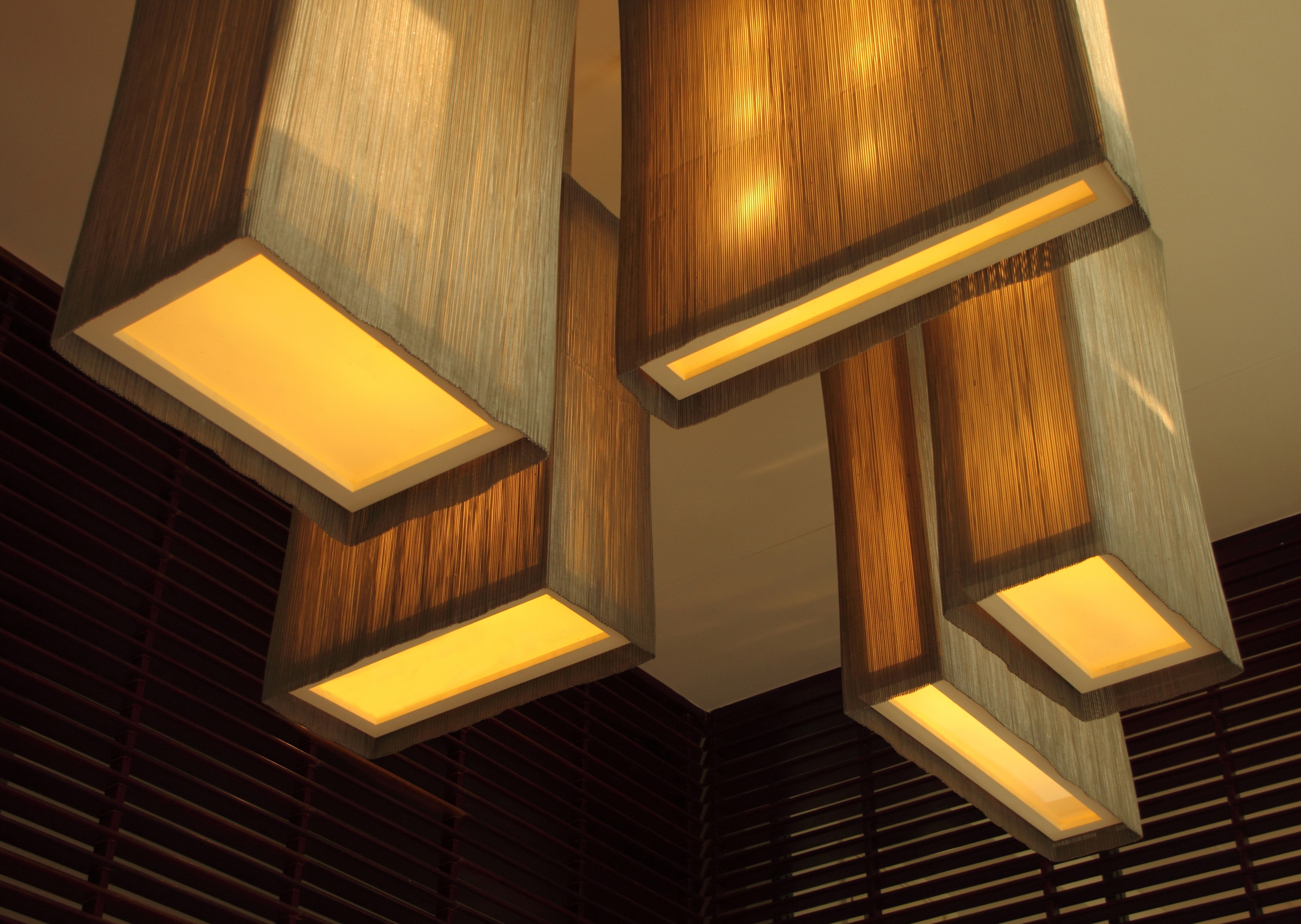

Avalon light mockup, Image © Archie Pizzini

Like you’ve said, normally the way of construction is changing towards standardization. Do you think there are any other possibilities?

HT: I think that we can accommodate both. I think that a lot of cities have been able to accommodate both ways. What we feel we are obliged to do is to call attention to what is already here. As Archie mentioned about the scale of operation, and we mentioned about the availability of all the resources, which are the material and the human resources, all of that contributes and makes this place work. I think there is always a sort of a shift back. For instance, some cities destroyed a lot of their texture and now they are trying to figure out a way to somehow synthesize it back. The idea is that if you can preserve enough of it we don’t have to go all the way through the cycle. We can keep some of it and find a way to make a more mature city, one that can take advantage of both sides.

Just to be able to identify, a lot of our works are not catered toward nostalgia, we don’t have that kind of attitude. I was talking about how cities accumulate and we are not trying to stop the process, we are very realistic about the fact that it will have to change, but we don’t want the city to be grown through development drastically to the point that everything that has happened and accumulated until now is replaced and we will be starting with a new layer.

Underlying System, Image © Archie Pizzini

AP: My research was called Observation & Negotiation at the Cultural Shoreline. A cultural shoreline is what I described to you earlier and the negotiation is finding how to practice in a situation like that. How can you take from everything that is there? How do you figure out what is advantageous and how do you make a determination of what is useful? What needs to be valued a little bit more than it is? And how can all of that be brought together in practice?

In Situ, Lost, Image © Archie Pizzini

In Asia, the markets for example, are tightly connected with the flow of space and time. How do you see this kind of phenomena? How does it work here in Vietnam? And do you think it will change?

AP: What I see in the more purely Vietnamese parts of the city is that there is a difference in the conception of public space. Public space is truly public. Incidentally this idea that the street is public space was actually worldwide until very recently. Erik Harms (the Yale anthropologist) talks about it and he has a wonderful quote where he says, that until recently, the best indication that you were anywhere of any importance in Vietnam was when the traffic stopped moving. And the feeling was that the street was actually for something different than transporting things through it. Its primary purpose was to serve as public space and then incidentally, people were also transporting things through it.

There was some interesting research just done about a change in that understanding in America that happened in the 1920s when the cars came in and the car industry actually orchestrated a campaign to change the understanding of how streets were used. When I first saw all the public space being used when I came here in 2000, it almost seemed like a gift that the government would let people use public space because they didn’t have anything else to give the people. “Because we are not a rich country, we are going to let you use public space and that is our gift to you.” At the time I thought that if that was the dynamic that was actually happening, it was a very good way of helping the people simply by not doing anything.

In Situ, Journey to the Present Rasquachismo, Image © Archie Pizzini

HT: I met someone recently, Marco Kusumawijaya from Jakarta, who was trying to differentiate the word public space from community space. Basically, community space is the real space that you are allowed to be in. But a lot of public spaces, for example in Jakarta, are off limits to the people. So those are public space because they are called public space specifically, but that is not community space, that is just merely a public space. He’s actually making a really big point and community space is where you are entitled because it is your right to go in there. A lot of the public space here in Saigon… I have been chased away a lot by security guards for resting in an urban park managed by a private company. Similar to Hong Kong. If you sit down it is ok – if you lean 45 degrees, a security guard will come and say “You can’t rest here.”

AP: I think that our coming to an understanding of the possibilities within the city and within this culture has greatly influenced the practice. For me personally, that has actually evolved. When I first got here we were doing a project, Avalon, which was almost the first realization and it was like ‘whoa there is something here that we can exploit and discover and try to see how far we can take it.’ Then, around 2007, we did our own office, HTA+pizzini atelier, where we just went a little crazy with all the stuff that we found that we could do and improvising details and everything else. And I have to say that it was like being almost drunk on the possibilities. The subject matter of that project was the possibilities of making. But once we got to this project, Galerie Quynh, the subject matter is actually the city. The making is in the service of producing a project that has the city as subject matter. One of the wonderful things that I find about Vietnam is that the idea of making has changed its role in the way that it participates in the projects. And now it is just part of us, it is part of our ability and research and practice.

In Situ, The City, Image © Archie Pizzini

What is the role of research in your architectural practice?

AP:I think that our coming to an understanding of the possibilities within the city and within this culture has greatly influenced the practice. For me personally, that has actually evolved. When I first got here we were doing a project, Avalon, which was almost the first realization and it was like ‘whoa there is something here that we can exploit and discover and try to see how far we can take it.’ Then, around 2007, we did our own office, HTA+pizzini atelier, where we just went a little crazy with all the stuff that we found that we could do and improvising details and everything else. And I have to say that it was like being almost drunk on the possibilities. The subject matter of that project was the possibilities of making. But once we got to this project, Galerie Quynh, the subject matter is actually the city. The making is in the service of producing a project that has the city as subject matter. One of the wonderful things that I find about Vietnam is that the idea of making has changed its role in the way that it participates in the projects. And now it is just part of us, it is part of our ability and research and practice.

HT: Earlier when I practiced, I had been thinking very much with an architecturally intuitive way of doing the work but after the research I started to fear that if I knew too much about what I do it might affect the way that I am doing things. I think it is a good thing but it is challenging because in the earlier days I was a lot more intuitive. Now I start thinking and sometimes I fear that I think too much.

AP: It’s not a problem for me, I have always thought too much! I think research and practice should come hand in hand and the more we do, probably the more comfortable I will feel about it.

HT: I think that somehow, I have to deal with it on a personal level to kind of try and reconcile but we have to do that.

In Situ, The City, Image © Archie Pizzini

And how do you see the future of HCMC?

HT: I recognize the good design that comes from Singapore, from Bangkok and from Jakarta, I think that HCMC is not really there yet. I also think a lot of people are still convinced that the West is the best and that new is better than the old but I think that is changing and a lot of the younger generation now are more aware. So I think a lot of it is due to exposure to the good stuff that is happening around. We are not having a manifesto or anything. We do things in a very small way but it is possible to make the best out of these very little things and if many of us do that, we will get there. If the younger architects are doing that and even the younger architects are doing that and build the city, there is still time.

AP: That being said doesn’t mean that there isn’t that risk, because the developers are moving very quickly too. But it’s probably normal. One of the things we have had to deal with more and more here, practicing in HCMC, is coming up against this idea of temporality. About how short lived everything is. In 2010 we realized that five of our best projects (we had only been in existence for five years) had already had a full life span and been demolished. It was like, ‘wait a minute…’ you know? So that sort of gets to the idea of temporality and how quickly things change and we had to accept that and then even incorporate it into our work. The other thing about understanding the temporality of things is coming to this understanding that no problem is ever solved forever.

In Situ, Journey to the Present Rasquachismo, Image © Archie Pizzini

HT: As architects we are trained to solve problems but you really can’t solve a problem forever. You fix it, you come to a good place, you create a solution and years later you have to do something different; you have to revisit the situations.

AP: When I got here in 2005 I think the median age was 25, and it is about 29 now and it has been going up but it is a factor because people in their 20s adapt very quickly and can change their understanding very quickly. It is a real factor in how things develop here in Vietnam and in HCMC. It could be a good factor or not but in this case I think that in a lot of ways it is spurring an embrace of new ideas. So there is reason for perhaps feeling like a new understanding is to come.

Archie Pizzini and Hoanh Tran, Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan