THIS 165-METRE-LONG CHILDREN’S HOME IN NORTHERN THAILAND CONFIRMS THAT DESIGN FOR A SOCIAL CAUSE CAN HAVE AMBITION MUCH GREATER THAN AN ARCHITECTURE LAB OR CHARITY

It has been said that only 10% of buildings in the world have been designed by architects. One of the main reasons for this is probably the fact that less than 10% of the population can actually afford hiring architects. The debate over the role and responsibility of an architect in society has been going on for decades. It is rather unfair to make any quick judgment, considering how architects only do what their clients wish. After all, architects are not investors. As a community architect, to design a decent, functional building is already a challenging task. In the meantime, on the other side of the spectrum, architects are still obsessed by the desire to render creative and functional control when it comes to design. This is probably why they feel somewhat hurt every time someone hangs a sarong in the minimal bathroom they attentively devise. Nevertheless, it is always delightful to see stories of community architecture as an emerging trend in the media. What should be further discussed are under what concepts these community architecture projects are conceived, what are the processes and to which level their architectural values should be categorized? In this case, Dhammagiri Children Home sets a good example of how architects and designers can take a professional approach toward socially driven work instead of treating it as an act of kindness. As Alejandro Aravena, the Pritzker Prize laureate once said, any given community project deserves ‘professional quality, not professional charity.’

BOTH THE HEIGHT AND SHAPE OF THE BUILDING ARE DESIGNED TO BE IN HARMONY WITH THE EMBRACING ENVIRONMENT

Dhammagiri Children Home was founded by the Dhammagiri Foundation and is the ‘home’ to over 60 underprivileged children aged 7 to 18 years old with different ethnic backgrounds such as Karen, Mong, Tai Yai, Leesor and Muser. Some of the kids are orphans and some come from families of poverty or insufficient fundamental needs. Dhammagiri Children Home is a design collaboration that has Ng Sek San, the prolific Malaysian landscape architect and founder of Seksan Design, as the designer. He worked with his fellows from different disciplines such as the architect Chris Wong, graphic designer Joseph Foo of 3nity Design, photographer David Lok and Tan Yew Leong, a filmmaker. The story behind the establishment of the foundation is just as interesting as the architecture. It all began with Malaysian Buddhist monk Ajahn Cagino, the former award-winning photographer, and his journey into the forest areas of northern Thailand where he came across people in the minority tribes and personally experienced the people’s struggles, especially the children’s lack of educational opportunities. Several families put their children under the monks and Ajahn Cagino’s supervision. This later led to the idea of building a proper home for the children. Ajahn Cagino’s first step toward fulfilling such intention was to ask for support and collaboration from his designer friends. An exhibition of photography was organized out of the attempt to raise funding, which eventually brought together the money for the establishment of the foundation and the purchase of the 7.9 acre piece of land that Dhammagiri Children Home would be built upon.

DERIVED FROM IMPERFECTION, THE BEAUTY OF THE ARCHITECTURE BECOMES MORE COMPLETE WITH THE CHILDREN MOVING AROUND, DOING THEIR DAILY ROUTINES

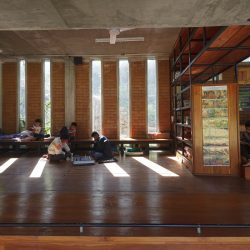

Reinforced concrete columns and beams were used for the building’s structure while the wall was simply constructed with bricks in order for the local artisans to be able to easily maneuver the work. The children under the care of the foundation helped out during the construction process, forming a sense of pride and connection with the place. The molding of flat slabs for the roof structure and ceiling uses Fak (strips of split bamboo), which left a beautiful natural pattern on the concrete surface. The children are familiar with this local material for it is used in the construction of their own houses. The floor plan properly divides the space with girls’ and boys’ bedrooms being separated and located at different wings of the building. Each sleeping area consists of bamboo bunk beds and a studying desk set at the end for the kids to do their homework on.

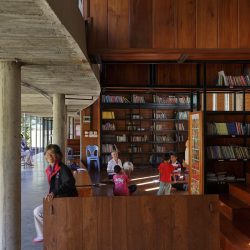

The space is flexibly partitioned by yellow curtains, which are similar in tone to the color of a monk’s robe. Pita Pawaro, the Chairman of the Sub-committee told us that the choice of the color was made to symbolically bring the children closer to dharma and the Buddha’s teachings. Next to the sleeping areas on both wings are communal bathrooms and lockers. The two wings themselves are linked together by the cafeteria adjacent to the kitchen at the back as well as a library (co-designed by the School of Architecture and Design, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi), a multifunctional area for praying and a computer room. The rooftop of the building is used for planting edible vegetables that the children take turns in shifts to care for. The children also tend to the paddy field set at the front of the building and, when the season comes, the children’s parents help with the harvest and cooking of meals.

NIGHTTIME AT DHAMMAGIRI AS GIRLS AND BOYS ARE HEADING TO BED IN SEPERATE WINGS OF THE BUILDING

At Dhammagiri Children Home, the harmony lies not only between the architecture and its surrounding environment and location but also the children’s natural way of life. The morning starts with the wonderful sound of the creek and the children waking up to their daily routine, which includes cleaning up the place, praying and meditation at the multifunctional area. They then hurry to take a shower, get dressed and board the bus to school. The home becomes quiet and peaceful again, filled with nothing but the sound of nature. At nearly five o’clock, the rascals are back to fill the house with their wonderful energy again. Some play football at the front of the building, some climb up to the rooftop, many work on the assigned chores be they laundry, sweeping, watering plants, cooking or etc. The minimal concrete building feels alive and vibrant with all the evening activities going on everyday in different parts of the compound. The raw and imperfect beauty looks even more attractive and ‘complete,’ with the presence of young spirits who do not seem to feel intimidated by the building’s simplistic space because it is their ‘home,’ the place where they can be safe and run free.

Dhammagiri Children Home is an architecture that is derived and driven by kindness, the wish and hope for a better world and a better society. Smart, humble, respectful to humanity and beautifully harmonious with nature and its surrounding environment, the architecture has enabled humans to be closer to dharma and nature. It allows for people to see that architects and designers can change their roles, from waiting for an investor to handle the financial side of a project and being a passive agent to becoming a strong active agent. By achieving that, underprivileged children are being given more opportunities and choices. The design and fundraising teams carry out their social projects by shying away from all the real-life dramas. They do not use the direness of people’s lives as a chance to carry out mindless architectural experiments. They attempt to exercise their creativity within the context that is limited with conditions, but at the same time, require a great deal of creative ability to come up with the most suitable solutions. Dhammagiri Children Home offers a chance for outsiders to finally learn that social service projects do need ‘professional’ designers, because apart from their compassionate hearts, everyone works together out of great fun and friendship. Joseph Foo, one of the leaders of the project’s fundraising team concluded that “the process of establishing this foundation was filled with laughter and delicious food. All the meetings, discussions and compromises were driven by friendship, love and a desire to change the society. We had a blast!”

ว่ากันว่ามีเพียงร้อยละสิบของอาคารบนโลกนี้เท่านั้นที่ออกแบบโดยสถาปนิก เหตุผลส่วนหนึ่งเพราะมีประชากรโลกไม่ถึงร้อยละสิบที่มีเงินพอจะจ้างสถาปนิก การถกเถียงเรื่องบทบาทและหน้าที่ของของสถาปนิกต่อสังคมมีมาหลายทศวรรษ จะว่าไปก็อาจไม่ยุติธรรมนักในเมื่อสถาปนิกมีหน้าที่ออกแบบตามผู้ว่าจ้าง สถาปนิกไม่ใช่นายทุน และหากว่ากันจริงๆ การเป็นสถาปนิกเพื่อสังคมนั้น แค่ออกแบบอาคารสักหลังให้ใช้สอยได้ดีก็ยากเย็นเหลือเกินแล้ว ในขณะเดียวกัน ทางฟากหนึ่งของงานออกแบบ สถาปนิกยังคงหมกมุ่นกับการออกแบบเพื่อการควบคุม สถาปนิกจึงเจ็บปวดทุกครั้งที่เห็นผ้าขาวม้าแขวนอยู่ในห้องน้ำสไตล์มินิมอลที่เขาออกแบบไว้ ส่วนอีกฟากหนึ่ง นับเป็นเรื่องน่ายินดีที่กระแสของการทำงานออกแบบเพื่อสังคมของสถาปนิกเริ่มมีให้เห็นในสื่อบ่อยขึ้น แต่สิ่งที่ต้องพูดคุยกันต่อไปคือ งานสถาปัตยกรรมเพื่อสังคมเหล่านั้นถูกทำขึ้นโดยยืนอยู่บนแนวคิดแบบไหน? มีกระบวนการอย่างไร? และมีคุณค่าทางสถาปัตยกรรมในระดับใด? ในกรณีนี้ โครงการ Dhammagiri Children Home เป็นตัวอย่างที่ดีในการแสดงให้เห็นว่าสถาปนิกและนักออกแบบสามารถทำงานเพื่อสังคมได้อย่าง “มืออาชีพ” ไม่ใช่ว่าทำไปด้วยความเมตตากรุณาเท่านั้น เหมือนดังที่ Alejandro Aravena เจ้าของ Pritzker Prize ได้กล่าวไว้ว่าสถาปนิกต้องทำงานเพื่อสังคมด้วย “professional quality, not professional charity”

Dhammagiri Children Home โดยมูลนิธิธัมมคีรี คือ “บ้าน” ของเด็กด้อยโอกาสกว่า 60 คน ที่อยู่ในช่วงอายุ 7-18 ปี หลากชาติพันธุ์ ทั้งกะเหรี่ยง ม้ง ไทใหญ่ ลีซอ และมูเซอ เด็กส่วนใหญ่กำพร้า บางส่วนยากจน ไม่ก็มีครอบครัวที่ขาดแคลนปัจจัยต่างๆ โครงการ Dhammagiri Children Home ออกแบบโดย Ng Sek San ภูมิสถาปนิกชื่อดังชาวมาเลเซียผู้ก่อตั้ง Seksan Design โดยเป็นการทำงานร่วมกับเพื่อนๆจากหลากหลายสาขาวิชาชีพของเขา ได้แก่ Chris Wong สถาปนิก, Joseph Foo กราฟิกดีไซเนอร์ (จาก 3nity Design), David Lok ช่างภาพ และ Tan Yew Leong ผู้กำกับภาพยนตร์ ที่มาของการก่อตั้งมูลนิธิฯ นั้นมีความน่าสนใจไม่แพ้การออกแบบ จุดเริ่มต้นเกิดจากการที่พระอาจารย์ชาคิโน ภิกขุ พระป่าชาวมาเลเซียผู้ซึ่งสมัยเป็นฆราวาสเคยเป็นช่างภาพมือรางวัล ได้เดินธุดงค์ไปในป่า ทำให้ได้เห็นความยากลำบากของชาวเขาเผ่าต่างๆ โดยเฉพาะเด็กๆ ที่มักขาดแคลนโอกาสทางการศึกษา มีชาวเขาหลายครอบครัวที่ฝากลูกๆ ให้พระอาจารย์ชาคิโนและคณะสงฆ์ดูแล ดังนั้นความคิดเรื่องบ้านพักสำหรับเด็กๆ เหล่านี้จึงเกิดขึ้น โดยในก้าวแรกนั้น พระอาจารย์ชาคิโนได้ขอความร่วมมือจากเพื่อนๆ นักออกแบบชาวมาเลเซียจัดแสดงนิทรรศการภาพถ่ายขึ้นเพื่อระดมทุน จากการจัดงานครั้งนั้นทำให้ได้เงินเพียงพอที่จะก่อตั้งมูลนิธิ ซื้อที่ดินกว่า 20 ไร่ และก่อสร้างอาคาร Dhammagiri Children Home ขึ้น

ภายในโครงการประกอบไปด้วยส่วนที่พักอาศัย ส่วนสำนักสงฆ์ ศาลาสำหรับผู้ปฏิบัติธรรม และแลนด์สเคปที่เป็นทั้งนาข้าวและแปลงพืชผักสวนครัวต่างๆ โครงการตั้งอยู่ริมลำธารและริมเชิงเขาในแม่ฮ่องสอน หากมองจากภายนอกจะแทบไม่เห็นตัวอาคารเลย เพราะอาคารคอนกรีตเปลือยสูงชั้นเดียวหลังนี้ได้สอดแทรกและเลื้อยตัวไปอย่างแนบเนียนกับบริบทโดยรอบ อาคารยาวประมาณ 165 เมตร และกว้างประมาณ 7 เมตร เป็นโถงโล่งกว้างที่มีเสาลอยแบ่งพื้นที่สัญจรออกจากพื้นที่ใช้สอย นับเป็นอาคารที่มีความถ่อมตนต่อสภาพแวดล้อมและโอบเอาธรรมชาติรอบตัวเข้าไปเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของพื้นที่ว่างเพื่อสร้างมุมมองที่สวยงามได้อย่างพิถีพิถัน ด้วยรูปร่างของผังที่ขดเลื้อยไปตามเชิงเขาแบบอิสระทำให้มุมมองจากแต่ละมุมบริเวณชานทางเดินนั้นสวยงาม ซึ่งเราก็รับรู้ได้อย่างชัดเจนเลยว่าผู้ออกแบบไม่ได้ออกแบบจากกระดาษสองมิติ แต่ออกแบบจากการลงพื้นที่จริงและการสร้างจริงที่ยิ่งกว่าสามมิติ เพราะมีทั้งกลิ่นหอมของดินชื้นๆ กลิ่นดอกไม้ใบหญ้า รวมถึงเสียงของนกและเสียงลำธารที่ไหลเอื่อยๆ ทั้งวัน พื้นที่ภายนอกและภายในอาคารจึงมีความเชื่อมโยงกันอย่างแยบยล

โครงสร้างของอาคารเป็นเสาคานคอนกรีตเสริมเหล็ก ส่วนผนังก่ออิฐแบบเรียบง่ายเพื่อให้ช่างท้องถิ่นทำงานได้ง่าย โดยในขั้นตอนการก่อสร้างนั้น เด็กๆ ที่ได้รับการอุปถัมภ์จากมูลนิธิฯ ได้มาลงแรงช่วยกันก่อสร้างด้วย ทำให้เกิดความรู้สึกของการเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของงานที่น่าภาคภูมิใจ การหล่อหลังคาแฟลตสแลปใช้แม่แบบเป็นไม้ฟากทิ้งร่องรอยของไม้แบบไว้อย่างสวยงามและทำหน้าที่แทนฝ้าเพดาน โดยไม้ฟากนั้นเป็นวัสดุที่หาได้ง่ายในพื้นที่ อีกทั้งยังถูกใช้อย่างคุ้นชินโดยทั่วไปในบ้านพื้นถิ่นของเด็กๆ อีกด้วย ผังพื้นอาคารแบ่งพื้นที่ออกเป็นสัดส่วน ส่วนนอนของเด็กหญิงและเด็กชายถูกแยกออกจากกันโดยตั้งอยู่ตรงบริเวณปลายอาคารในแต่ละด้าน ภายในส่วนนอนประกอบด้วยเลเยอร์ของเตียงไม้ไผ่สองชั้นที่มีโต๊ะอยู่ปลายเตียงสำหรับนั่งทำการบ้านได้ คั่นปิดพื้นที่ในเลเยอร์ที่สองอย่างยืดหยุ่นด้วยผ้าม่านที่มีสีเหมือนจีวรพระอย่างตั้งใจ พระอาจารย์พิทักษ์ปวโร ประธานอนุกรรมการฯ เล่าว่าสีของผ้าม่านนั้น เพื่อเป็นสัญลักษณ์ให้เด็กๆ รู้สึกใกล้ชิดธรรมะ ถัดมาจากส่วนนอนของแต่ละฝั่งคือพื้นที่ของห้องน้ำรวมและล็อคเกอร์ เชื่อมกันตรงกลางด้วยส่วนกินข้าวรวมที่อยู่ติดกับครัวทางด้านหลัง ห้องสมุด (คณะสถาปัตยกรรมศาสตร์และการออกแบบ มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าธนบุรีมาร่วมออกแบบด้วย) พื้นที่อเนกประสงค์สำหรับสวดมนต์ไหว้พระ และห้องคอมพิวเตอร์ หลังคาของอาคารถูกใช้เป็นพื้นที่ปลูกพืชผักสวนครัว โดยเด็กๆ จะผลัดกันจัดเวรคอยรดน้ำและดูแลทุกวัน นาข้าวที่อยู่ด้านหน้าอาคารปลูกโดยเด็กๆ เช่นกัน โดยเมื่อถึงฤดูเกี่ยวข้าวผู้ปกครองของเด็กก็จะมาร่วมช่วยกันลงแขกเกี่ยวข้าวและหุงกินกัน

นอกจากอาคารจะกลมกลืนไปกับสภาพแวดล้อมและพื้นที่ตั้งเป็นอย่างมากแล้ว อาคารยังมีความเป็นอันหนึ่งอันเดียวกันกับการใช้ชีวิตตามธรรมชาติของเด็กๆ ในบ้านอีกด้วย ตั้งแต่เช้าตรู่นอกเหนือจากเสียงลำธารที่ไหลเอื่อยๆ เราจะได้ยินเสียงเด็กๆ ที่ทยอยตื่นจากส่วนนอน เดินมาทำวัตรสวดมนต์ และนั่งสมาธิกันอย่างสงบบริเวณโถงอเนกประสงค์ จากนั้นเด็กๆ จะพากันกุลีกุจอไปอาบน้ำแต่งตัวและขึ้นรถไปโรงเรียน บ้านจึงกลับมาเงียบและได้ยินแต่เสียงธรรมชาติแวดล้อมอีกครั้ง จนเกือบห้าโมงเย็น เด็กๆ กลับจากโรงเรียน อาคารจะถูกเติมเต็มด้วยเด็กๆ ที่บ้างวิ่งไปมา บ้างเล่นฟุตบอลที่เนินดินหน้าอาคารกันเป็นกลุ่ม บ้างปีนเสาขึ้นไปเล่นบนหลังคา บ้างทำงานบ้านตามเวรที่ได้รับมอบหมาย เช่น ซักผ้า กวาดบ้าน รดน้ำต้นไม้ ทำครัว อาคารคอนกรีตที่เรียบง่ายดูมีชีวิต และสีสันเมื่อเด็กๆ แทรกตัวทำกิจกรรมอยู่ในแต่ละส่วน อาคารที่มีความดิบและความสวยงามจากความไม่สมบูรณ์เป็นทุนยิ่งดูสวยและ “เต็ม” ยิ่งขึ้นด้วยเด็กๆ ที่ไม่รู้สึกถูกข่มใดๆ จากพื้นที่ว่างที่เรียบง่ายพวกเขารู้สึกว่านี่คือ “บ้าน” ที่เขาสามารถวิ่งเล่นได้อย่างอิสระ

Dhammagiri Children Home เป็นสถาปัตยกรรมที่เต็มไปด้วยไมตรีจิตที่มุ่งหวังให้โลกและสังคมดีขึ้น เป็นสถาปัตยกรรมที่ฉลาดถ่อมตัว เคารพความเป็นมนุษย์ และเป็นอันหนึ่งอันเดียวกับธรรมชาติและสภาพแวดล้อม เป็นสถาปัตยกรรมที่เอื้อ (enable) ให้มนุษย์ได้ใกล้ชิดธรรมะและธรรมชาติ เอื้อให้คนอื่นๆ ได้เห็นว่าสถาปนิกและนักออกแบบสามารถเปลี่ยนบทบาทตนเองจากผู้รอนายทุนเป็นผู้ระดมทุน หรือจาก passive agent เป็น active agent ได้ เอื้อให้เด็กที่ขาดโอกาสมีโอกาสและทางเลือกในชีวิตมากขึ้น ทีมนักออกแบบและทีมระดมทุนไม่ได้ทำงานเพื่อสังคมด้วยความดราม่าฟูมฟาย ไม่ได้ใช้พื้นที่ของความลำบากขาดแคลนของผู้คนเป็นสนามทดลองทางสถาปัตยกรรมที่ไม่เข้าท่า หากแต่พวกเขาทดลอง exercise ความคิดสร้างสรรค์ของพวกเขาในพื้นที่ที่มีเงื่อนไขของความจำกัดและในขณะเดียวกันก็เป็นพื้นที่ที่ต้องใช้ความคิดสร้างสรรค์ในการแก้ปัญหา Dhammagiri Children Home เอื้อให้คนภายนอกได้เรียนรู้ว่าการทำงานเพื่อสังคมต้องการนักออกแบบที่เป็น “มืออาชีพ” ที่นอกเหนือจากการมีใจที่เมตตากรุณาแล้วนั้น พวกเขายังทำงานร่วมกันอย่างสนุกสนานและมีไมตรีจิต Joseph Foo หนึ่งในแกนนำผู้ร่วมระดมทุนกล่าวสรุปว่า “กระบวนการสร้างมูลนิธินี้เต็มไปด้วยเสียงหัวเราะ อาหารอร่อย การประชุม การถกเถียง และการประนีประนอม มันเต็มไปด้วยมิตรภาพ ความรัก และการเปลี่ยนแปลงสังคม โดยที่พวกเราสนุกสนานกันมาก!”

TEXT : SUPITCHA TOVIVICH

PHOTO : SOOPAKORN SRISAKUL except as noted

dhammagiri.or.th