FROM THE DELICACY OF DETAIL IN BAMBOO TO THE VITALITY OF CREATING AN URBAN STRUCTURE, art4d SPOKE WITH VO TRONG NGHIA ABOUT HIS AIM TO EXPLORE EVERY POSSIBLE WAY TO GO BEYOND THE EXISTING STANDARDS

What have you learned from studying architecture in Japan?

Vo Trong Nghia: I went to Japan in 1996 and lived there for 10 years. My architectural education started in Japan, so my approach toward architectural practice and ideas were influenced by Japanese education a lot — or better say, it came entirely from the education in Japan. I was lucky. I began my studies at the National Institute of Technology Ishikawa College (Ishikawa Kosen), which has a very strict discipline. The college seems like a school in the middle of the woods. It is located in a small town with a very good environment.

As for the university life, I entered Nagoya Institute of Technology (Meikodai) and met Professor Shigeru Wakayama, who is a very talented architect and instructor. What he did was not only to teach me how to think, but also to allow me to think and work freely. Later on, when I got into the Graduate School of the University of Tokyo (Todai), I was again allowed to do whatever I wanted. Professor Hiroshi Naito talked to me only about once every six months. Once he said, “you’d better study building structure again.” Such a big ‘assignment’ came once in a while; then I had to study really hard for six months to understand it.

“Wearing a white shirt used to be a rule for everyone in the office but not anymore. We created that rule because we wanted to create a professional atmosphere, but we don’t need that rule anymore.”

VTN: At the beginning of my studies, Naito-san once said, “The mountain you’ve made is bigger than anyone’s in the class, but it won’t get any higher. You have to topple it and restart making again from its foundation. The foundation must be wide and deep, so that you can build your mountain as high as you want.” He compared metaphorically my architectural skills to the mountain. Afterwards, I began to study building structure and also fluid dynamics.

He once came with a list of architects featured on Japanese architectural magazines Shinkenchiku and Jyutakutokushu and said, “There are hundreds or thousands of architects in Japan who are able to build all these beautiful works. In Japan, if you only can build beautiful works, you won’t go any further. If you want to go beyond the horizon, you have to be cultivated and knowledgeable.”

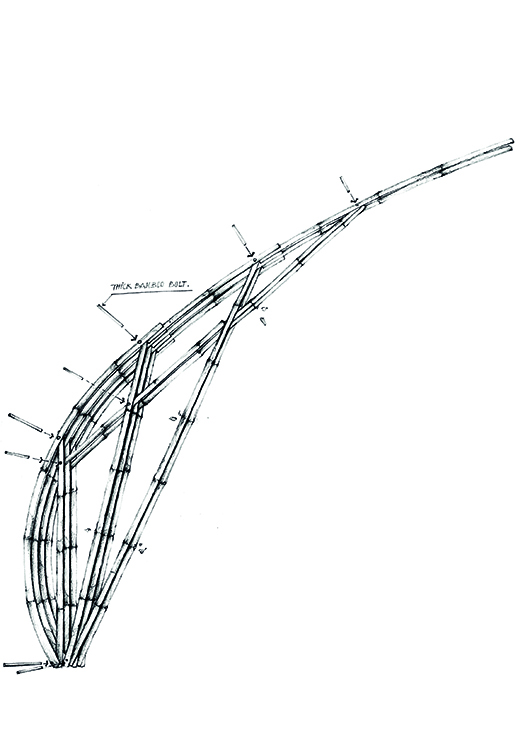

Sketches for Wind and Water Bar, Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

After you graduated, why didn’t you continue your practice in Japan?

VTN: I cannot work all night without sleep. I can keep focusing on my work in the right time but I can’t stand deprivation of sleep. Japanese architects sometimes start meetings at midnight, right? It’s just too much.

KOSUKE NISHIJIMA: Only that?

VTN: Yes. (All laugh) That’s why I don’t introduce such a way of working into my office. My office starts working early in the morning and I focus on my work for 8 hours. After I call it a day and leave the office, it depends on each staff, whether they will continue working or not — most of them clock out around 7-8 PM. We work seriously with great concentration and then take a rest.__

Sketches for Wind and Water Bar, Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

With your eyes used to Japan, how did you see Ho Chi Minh City after coming back?

VTN: I thought that there was great opportunity, and a great chance to start making something here. It seemed that a lot of things were waiting to be done. On the other hand, the city was quite messy and lacking of trees.

KN: Did you find it necessary to recover greenery in the city right after coming back from Japan?

VTN: Yes. I was born and raised in a rural area in Vietnam that has plenty of trees, a beautiful river and a wonderful environment all around. When I was a student of Kosen in Japan, I was still living in an excellent environment. That’s why I feel uncomfortable living without trees and have tried to use trees to bring greenery back into the city since the beginning.

The air pollution is also one of the main problems. People in the city seem to be gloomier year after year. Before I went to Japan, the speed of life in a Vietnamese city such as Hanoi was pretty slow; everybody enjoyed a slow living, riding their bicycles together slowly during the winter. It was fantastic! However, such a romantic atmosphere no longer seems to exist. Now, everyone rides a motorcycle and the traffic is extremely heavy.

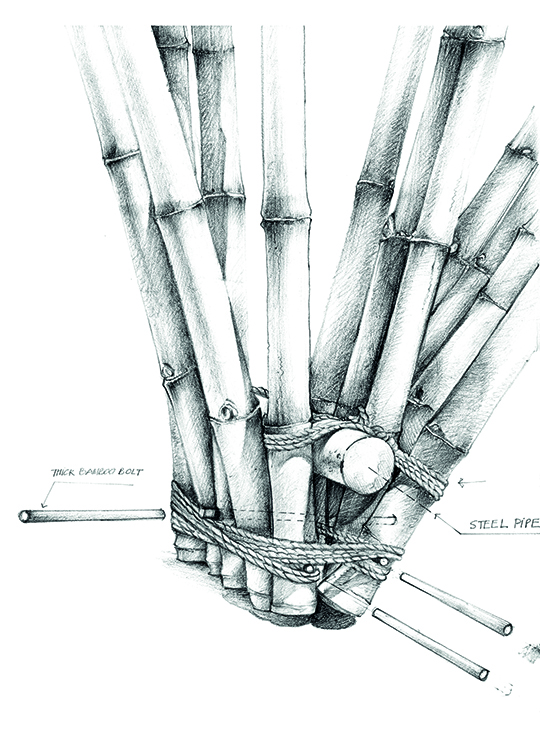

One of their earliest experiences with bamboo, WNW Cafe’s spacious wide span is supported by a beautifully flexible bamboo structure that has been processed by traditional methods such as soaking in mud and smoking. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

KN: Now it seems like everyone is striving to be the first.

VTN: There are lots of people out there calling for more development; but for me, such development has caused people to live with increasingly more difficulties.

How did you arrive at bamboo?

VTN: When I first came back to Vietnam, bamboo cost just 0.50 US dollars. I got the idea that we must try to do something with this good and low-cost material. Coincidentally, I was working on a project called Wind and Water Cafe. I used around 7,000 pieces of bamboo which cost only 3,500 US dollars. I was amazed that this price could achieve an entire coffee shop.

KN: I’m wondering, when did you think of using bamboo for your project? Did you already have the idea when you were in Japan?

VTN: Yes. When I was in Japan, I took up bamboo as a part of my thesis. I knew that it was inexpensive but I didn’t known before that bamboo could be this good and this low-cost.

In order to maximize the wind, the shape and the layout of the cafe have been studied carefully through CFD analysis. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

When we went to visit your works, we felt a special quality in the way that you used an organic material like bamboo systematically.

VTN: I don’t want to work with bamboo perfunctorily. I don’t want to make it like a handicraft because it would be harder to ensure the maintenance of such kind of thing. I don’t call it sustainable even though it has been mentioned a lot when people talk about sustainability. I think it is wasteful if we cannot fix the gradually eroding quality after 10 to 15 years. That’s why I try to make bamboo into a unit so as to control the quality of the structure and to allow for it to be more easily maintained. For me, bamboo has to be used in this way.

When I was in Japan, I was involved in a project in Kanazawa to build what was the tallest wooden structure in Japan at that time. While doing the project, I was always thinking about how to transport wood from the production area to Kanazawa and how to assemble it quickly as well. So, when I started to work with bamboo, I tried to adopt the way that I worked with wood by creating a unit and duplicating it.

Without using any metal fixtures, 48 prefabricated units of a 10M tall and 15M wide bamboo arch were bound together with rope. This is their first experiment with systemized bamboo construction. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

Your office is very international but you still use a local approach as well. How do you manage and create a system in your office?

VTN: For me, to create the system is very important. We discuss with all partners, Nishijima-san, Sawa-san and Niwa-san, about how to make the system in a better way. I’d say, creating architecture, even a single project, is quite difficult, but it’s still easier when compared to creating a system.

There are many things to consider in a project: Who’s going to be accountable? How long will it take to complete? How can we achieve the desirable level of quality? We must control all of those things. I had no experience working for an architectural firm before. We also try to borrow from the power of meditation to get through all problems.

What we are currently trying to do is to establish a system to control working hours in each project and an accounting system that won’t make us go into the red. In order to achieve this, I’ve moved to the accounting room so that I can control and manage everything there. Actually, I just moved my desk yesterday.

Located in the middle of an artificial pond, the Bar is naturally ventilated by the air cooled by the surrounding water. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

What about the construction? How do you manage it?

VTN: We worked very hard for that. Latterly, our construction sites are very neat and in good order, almost like in Japan.

How?

VTN: Site cleaning is the first thing; we add another budget for cleaning and uniforms to a regular contract. Without paying, they would never listen to us.

KN: Vietnamese construction workers sometimes use a helmet as we use a bucket. They wear flip-flops at the construction site, which is quite dangerous and inefficient.

VTN: For bamboo works, I used to hire those hooligans from my hometown in the countryside. When I went back there some years ago, I saw the painful plight there and it worried and caused me to imagine that the youngsters in the countryside were going to die. That’s why, little by little, I’ve hired them as bamboo workers for us.

However, it didn’t work well. They started to snitch our stuff from construction sites. Recently, I’ve just dismissed the team. After that, I found workers from another place, and later, I called my old folks from the village back to join the team but just only three people at a time, and they have to join a meditation camp before starting work again.

This project is special in terms of the construction method. Not using fabricated bamboo units, these 24M-diameter-domes are woven like traditional baskets due to the special conditions of the location. For Nghia, this is a ‘fusion of traditional folk art and contemporary architecture.’ Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

You also sent the construction workers to the meditation camp?

VTN: Yes, I went to the last course together with them. We had to meditate for 10 hours every day throughout the course, and we are not allowed to go anywhere. When we returned from the camp, the workers told me that they wanted to go back to the camp again.

I was amazed that all these guys had come this far. Recently we introduced a clear order of working at our construction site. The workers start working from 7 AM to 9 AM and a 20-minute break will follow. Then, they continue the work for another 2 hours before lunch. The quality of the work has improved a lot thanks to the new system.

The first prototype for a low-income house built with a lightweight steel frame and bamboo. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

Can you tell us about the low cost house series?

VTN: The project is so deep. Nishijima-san has been in charge of that project since the beginning. We’ve failed again and again, especially in terms of the price. We’ve almost reached 2,000 US dollars for a 30-square-meter house, but it is still too expensive. It should be 1,500 USD for 30 square meters or 1,000 USD for 20 square meters, otherwise it could not work. For the assembly, we’ve become experts already and it takes only 3 hours to complete the frame structure. Our purpose with the design is that any builders can build the house with the same quality. However, it may need 2 or 3 years more to accomplish all targets. There are so many issues to be solved. For example, the one made of concrete (S House 2) was designed very well, but each piece of concrete was too heavy that even our tough workers felt difficulty to work with it. This means, ordinary people could never build it by themselves. After we realized that, we designed the next version from scratch, but we had confidence this time — everything was perfect — with lightweight components and an easy assembling system; though we were still stuck on the price.

For us, this project is the biggest and the most important project in the company. We have put great effort and energy into it.

The second prototype was built from precast concrete with Nipa Palm Panels to increase durability and affordability. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

What are you going to do with it after you accomplish all the targets?

Once we can make it, we will start mass production and sell the house all over the world — especially in places with a high demand that suffer from natural disasters or wars. For those places, nothing could be better than this – the house that could be built in 3 hours. And it is durable too. Oh yes, I only appreciate things that could last long!

KN: Our low cost house project is distinctive in terms of longevity. IKEA has designed an extremely economical house for refugee camps but it can be used for only 2-3 years. What we are trying to do is to create a house that can last for 30 years. The most difficult part of the project is to think about how we can reduce the cost until getting closer to IKEA.

The third prototype combines the successful elements of the first and second prototypes and by adding a slender steel lattice to the lightweight steel frame, the rigidity of the house was increased allowing for a minimization of the quantity of steel required. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

Could you share with us more about the term ‘longevity’ from your point of view?

VTN: I’m thinking that it is almost a crime to build fragile architecture that doesn’t last long. For example, if a pavilion is designed to be demolished within a year or so, then it doesn’t need to be durable. However, we should not build architecture that will collapse within 2-5 years. All of those works are created by architects who imagine architecture to be ‘interesting.’ A lot of architects tend to use the word ‘interesting’ to achieve something they like, however, it’s not my taste. The longevity is one of the most fundamental factors of a sustainable architecture, isn’t it?

KN: You once told me about a story from your elementary school age, and it could explain the issue a lot. Nghia was born in a countryside where the school looked like a shanty. And it was always blown away by big storms.

VTN: And then we had no class for three months. (All laugh)

KN: And it happened every single year. That’s how fragility of building became taboo to you, right?

VTN: Yes, I hate it. Just a few days ago, we were discussing about how to enhance the strength of our bamboo structure.

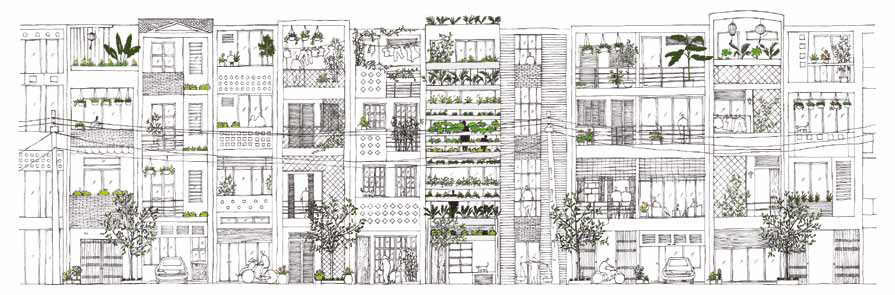

Stacking green elevation which depicts their vision: ‘Visible greenery is profitable not only for its owners and residents but also for the community, inspiring and encouraging people in cities to install more greenery onto their buildings.’ Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

KN: This issue often brings conflict to the construction site. Contractors usually have different opinions about the strength of structure from us. For example, usual concrete columns or slabs in Vietnam are extremely thin compared with our standard. They seem to have their own standard but we don’t agree with it. We ask double or triple more than that. The trouble is that they never understand why we want to do that. Actually, we do not understand it clearly either. We can’t simply compare it with Japanese standards due to the different climate and environment. Our criteria comes almost from an instinct.

VTN: For the bamboo structure, we should say that it is kind of our instinct. But for the concrete, we make it strong by experience. I’ve seen works of Kunio Maekawa, Fumihiko Maki and Togo Murano, and I think that they are so good; so good that there seems to be no need for maintenance at all. I want to keep my projects without any claim for my whole life. (All laugh)

KN: What is different from Japan is that we can’t immediately believe the calculation that we receive from engineers because it has been calculated with the current Vietnamese standards. And such standards would change sooner or later. When we consider whether a structure can last for another 20 or 50 years, we can’t simply count on the current standard.

Future perspectives show their vision: Building should be transformed into house greenery.’ Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

While the city keeps changing more and more, we feel that something like a market or a periodic vendor seems to be one of the most distinctive characteristics of Asia. In terms of the city, what do you think about this change?

VTN: Right now, we are working on the ‘House for Trees’ project. After we finish the first project, we were thinking that even a tiny house could work as a small garden in a big city. I’m delighted to see that there are lots of Vietnamese architects who have started working on green buildings.

KN: Nghia has an infrastructural way of thinking, I think. He wants not only to be an ‘architect,’ but also to be a person who creates a kind of foundation of the city, meaning he is creating an urban structure or a skeleton of the city but not just a periodic movement. He has a strong attachment to something strong and stable and I was influenced by such attitude a lot.

Following the project name, this house is literally a prototypical house to return green space into the cites. Image © Vo Trong Nghia Architects

VTN: The residential buildings in Vietnamese cities are normally so dense that there is no ground to have greenery any more. Our goal is to have more green space for trees in the building, let’s say at least 200-300% of the land. For instance, if there is a 100-square-meter plot, we try to stuff a 200- to 300-square-meter green space into the building. Today’s Vietnamese architects also share this kind of slogan — more natural trees, more natural light, more natural ventilation. This starts to become a standard little by little, and I think that is fantastic.

So what do you think your next step will be?

VTN: I’ve recently been writing letters to the government. I’m trying to encourage them to hurriedly create laws and regulations such as: “if you want to build a building of this size, you must have this much green space.”

And Nishijima-san, what have you learned the most from this office?

KN: I learned a lot. One should be the real earnest attitude with which to make architecture, in order to create architecture that works properly and can be maintained with good performance. I also learned how to set up a system in the office. And… smiling. I learned a lot from the way Nghia communicates with clients.

VTN: That’s very important. It’s a matter of tolerance because there are various types of clients we have to communicate with. Meditation must help for this. It teaches you about tolerance and patience.

Kosuke Nishijima and Vo Trong Nghia

INTERVIEW BY: B SIDES

www.votrongnghia.com