DELVE INTO THE STORY OF A THAI RESEARCHER AT THE MIT MEDIA LAB, HIS ADVENTURE IN THE LAB, AND HIS POINT OF VIEW ON AI

TEXT: NATHATAI TANGCHADAKORN

PHOTO CREDIT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

While the wildly divergent views and ongoing debates on AI (artificial intelligence) still seem like an unsettled swirl of dust, art4d spoke with Pat Pataranutaporn, a Thai student and researcher currently studying and working at the MIT Media Lab of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the world’s most prestigious science and technology research centers. Our conversation took place thanks to CREATIVE BUSINESS CONNEXT, an event hosted by the Creative Economy Agency (public organization), or CEA, to which Pat was invited as one of the speakers of the Creative Unfold forum, themed ‘VISIONAIRE: Reminisce/The Way Forward.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

To give everyone a brief introduction, Pat was born in Songkhla, a province in the south of Thailand. He is currently working as a member of Fluid Interfaces, an MIT Media Lab research group. Pat was a Junior Science Talent Project (JSTP) participant since he was in middle school and a co-founder of the Futuristic Research Group (Freak Lab) in Thailand. Pat received his bachelor’s degree from Arizona State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences prior to attending MIT, revealing that his combined interest in art and science has been a long one.

‘Making Food with the Mind : Connecting Food 3D Printer with BCI’ one of Pat’s projects before entering MIT Media Lab | Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

In this interview, art4d asked Pat about his current thoughts on the two scientific realms on which he has been conducting his research. Pat believes that AI will not replace but rather help humans, and that studying the interactions between AI and humans is equally crucial to the advancement of AI’s intelligence level. This is because the goal and purpose of AI are not to surpass the human race and leave everyone behind, but to evolve in ways that can aid and support humanity. That is why Pat’s interest lies not in AI (artificial intelligence) but more in IA (intelligence augmentation)

art4d: What’s the origin story of you working at MIT Media Lab?

Pat Pataranutaporn: It actually began when I was a kid. I’ve always loved science fiction, Doraemon, and Iron Man—those types of stories. Science, to me, seemed to be about futuristic stuff like developing a time machine and reproducing dinosaurs. I’d wonder why I hadn’t gotten the chance to study that kind of science. Why were we learning science in a classroom rather than how Nobita was learning in Doraemon? Nobita was failing school, but he got to go on all these space adventures and incredible places. It had always puzzled me why the science I was studying in class and the one depicted in movies were so dissimilar. Later, I realized that there are people undertaking futuristic scientific research like they do in movies, like at MIT’s Media Labs and other departments. They’re all doing so much cool stuff.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

I used to be fascinated by dinosaurs as a child. My parents would advise me, “If you like dinosaurs, you should study science because it will help you understand the anatomy of the creatures. But you must pay attention in art class since it is where you will learn how to draw dinosaurs.” That’s when I began to associate art with science. I’ve never thought of them as two distinct entities because, to me, they were like these two different parts that help bring dinosaurs to life.

The name Media Lab is derived from the word ‘media’ or ‘medium.’ It is the intersection of art, science, design, and engineering. I feel like it’s a perfect match in the sense that it’s doing things for the future and that it’s bringing together my interests in art and science.

art4d: Could you tell us about the research that you’re currently doing?

PP: My research group is one of Media Lab’s research labs. It’s called Fluid Interfaces. Our focus is on fluid, which has nothing to do with liquid substances or anything like that, but rather ‘fluid’ in the sense of how to enable the seamless integration of humans and technology. The group consists of 20 – 30 members, and each of us does our own research on a variety of aspects of humans and technology.

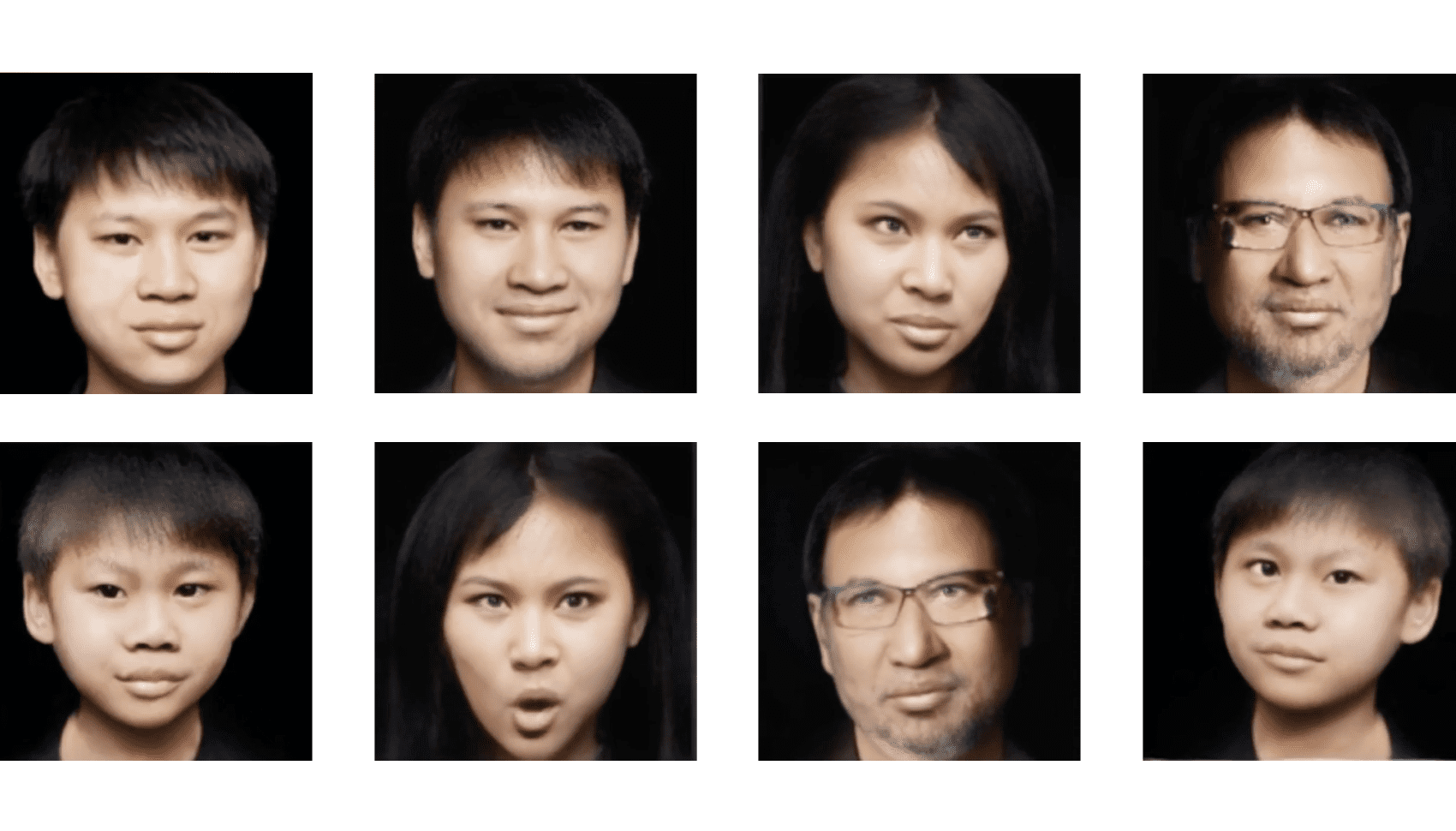

My particular area of interest is digital characters, which is essentially creating virtual beings. Many people have asked me if I’m inventing technology to replace humans, but that’s not what we’re doing. We’re developing virtual humans to help actual humans better understand and learn about themselves.

art4d: Could you offer us a few examples of previous projects done by Fluid Interfaces?

PP: Professor Pattie Maes, who runs Fluid Interfaces, has revolutionized the world with three breakthroughs. The first is the recommendation system, which came at a time when computer software was passive and had to be told what to do. Pattie pioneered the active recommendation system three years ago, and it has since evolved into the ‘recommended for you’ feature that we see today. AI can recommend information or items that we might be interested in. That was one of the innovations created by Fluid Interfaces three decades ago.

‘Wearable Lab on Body’ | Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

The second period revolved around questioning why everything had to be behind a screen or on a computer. Why couldn’t they be integrated into our lives in every dimension? As a result, wearable technologies such as smart watches and smart eyewear were introduced. Pattie’s group is considered the origin of these inventions. Many of his students go on to become executives at companies like Samsung and Apple.

Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

In its third era, the lab studies wearables, as in computers that have been placed on human bodies. The computer can determine whether or not we are getting enough sleep, for example. However, people’s behavior does not always change as a result of what computers tell us. Or how having computers inform you that you have a limited attention span might make you feel even more stressed. So this is the age of augmentation, in which technology should help us improve our ability and potential, whether by making us sleep better, concentrate better, think better, or become more creative, rather than simply providing us with more information. We’re talking about developing different aspects of human cognitive capability.

art4d: Using technology as a tool can have a detrimental impact on its users; how can you control the negative repercussions as a creator?

PP: I like this one statement made by a technology philosopher that technology is neither negative nor positive nor even neutral. It is not inherently good or evil, but rather depends on how people utilize it. At the same time, it isn’t entirely neutral because the values of users or creators are also reflected in the technology. I don’t believe that developing innovative technologies is going to automatically make our lives better. AI may deceive us if it is programmed to do so, or it may assist us in learning more effectively. In the end, it is a question of how it should be complemented or connected to humans in order to achieve such a result. That’s a significant question that most people haven’t given much thought to.

I believe that the most useful discipline for future developments will be human-AI interactions or human-computer interactions, which involve fundamental human-computer relationships. It’s not just about computer science or computer engineering; it’s also about understanding the psychology behind everything, as well as human behaviors.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

art4d: What do you think will happen if technical advancements continue without a clear and defined purpose?

PP: One issue is a departure from humanity. It may also compel humans to become or act in a certain way. It’s just that we need to build technology that enhances humanness rather than dehumanizing people. While we are developing AI to be smarter and do things that mimic human intelligence and behaviors, we are also establishing an education system that forces individuals to act or perform like robots. It’s both an intriguing and dangerous paradox, in my opinion.

art4d: What are your ideas on the development of AGI (artificial general intelligence) and when will it actually be possible?

PP: We still don’t know when it will happen or how long it will take because humans don’t have a clear definition of what AGI is. First and foremost, how do we define intelligence? The first question is whether what AI is capable of doing now, in terms of the answers it generates, is sufficient or not. Years ago, we could definitely go on Google and find the answers we were looking for. They are, at their core, comparable. Is it really intelligent? To what extent will the concept of ‘general’ have to be integrated into our minds for us to say that it is sufficient? Because these words still lack definitions, there has been no way for us to determine what is right and what isn’t. Many times, the answers to these questions are emotionally driven. For example, one can feel that this object is intelligent or anything along those lines, so it ends up being something that people are still debating over.

At the end of the day, whether AGI or non-AGI, the question we should ask is what will happen to the human race. AGI is one of the tools, and in this world, we are always discovering new technologies and entering new realms. We are developing a plethora of technologies that we rarely see or realize, such as clothing. The most profound technologies, according to computer pioneer Mark Weiser, are those that disappear. We’re still excited about AI because it’s so new, but once it’s seamlessly interwoven into our lives, that’s when it becomes truly powerful.

If you ask people today if they believe Google is very innovative, the majority will say no. We’ve seen real humans engage with AI in sci-fi movies, and it feels completely normal to us now. Think about Doraemon and how far ahead of its time it was (laugh). Doraemon is a walking chatGPT, if not better. Nobita never felt frightened by Doraemon or feared that it would rule the world or replace him, right?

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

art4d: Do you believe that the way AI is evolving will cause humans to be skeptical of it even more, aside from the copyright issues?

PP: We humans have various approaches when it comes to problem solving. We do not only have intelligence, like AI does, but also emotional intelligence and artistic intelligence, all of which are interwoven with creativity and emotions. So when we talk about AI, it’s just in the context of how we interpret human intellect. To begin with, the copyright issues are just technical problems that can be resolved by drafting the right law. For example, if an artist owns the data used to train AI, how much should they be paid? This is a technical issue that can be legally handled if discussions are carried out, and I believe we will be able to find a solution.

The important question we have to ask today is what skills humans should have if they are something that AI can do. That question has two levels to it. The first is a set of questions that arise at a certain point in time—all of the challenges that have to do with AI today. The second level is that if we assume that AI will be able to learn everything that humans can potentially learn with such great efficacy, what are the things that are truly significant to humans?

Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

To me, anything I find pleasurable—things that humans still find joy in doing—I believe we will continue to do. We have these opportunities to eat at restaurants where we know chefs are better than us at cooking, yet we still like home-cooked meals. Another advantage is that we will be able to see things from a different perspective. Instead of making art, we will find ways to explore possible innovative, novel artistic mediums that no one has ever thought of before.

Creativity is escaping the box, and AI helps us come closer to breaching that box faster because it can accelerate the speed from 0 to 100 in the span of 5 seconds. But the question is, what is beyond that box? That is the question that people in the future are going to have to ask.

art4d: What should be the starting point for a research project with the potential to create a paradigm shift?

PP: This is a critical question. We’re dealing with a lot of problems these days, aren’t we? And people are wondering why we’re not doing research on such and such topics and why we’re doing research on something so abstract that doesn’t make much sense to them. However, I believe that successful research stems from something personal to the researcher. So, in my opinion, a good research project must 1) be personal, 2) integrate interdisciplinary knowledge, and 3) tackle significant and meaningful subject matters. These factors, in my opinion, make a paradigm shift.

A lot of the time, paradigm shifts happen by chance. Many scientists throughout history have discovered something purely by coincidence, such as an apple falling on Newton’s head. So having the freedom to explore and think beyond the box is incredibly important.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

art4d: Science is logical, with causes and effects; as someone who studies both arts and science, do you believe arts are logical, and does everything need to have a definition?

PP: When I was an undergraduate, we had a class called Human Event, in which we studied literature from a different perspective. We looked at literature not as literature but as a reflection of what society was like at a specific time. It is an attempt to challenge the logic of a society or culture at a given time period, as reflected in literature. It’s an interesting way of looking at it. That class taught me that whether or not a piece of writing has logic behind it, there is generally some type of force that propels and releases those ideas. That force can be social issues, imagination, or the creator’s built-up stress. It is not necessarily logical reasoning, but it is a form of ‘logic.’

This cycle of repeated patterns can be seen throughout history. People who do not know history are cursed to repeat the same actions over and over again without understanding what is going on. There is intelligence in everything, whether it be the arts or science. If we can identify how these intelligences relate to one another, we will be able to see that there is much more to this world.

art4d: Tell us about the origins of Conversation with the Sun now that we’ve entered the artistic realm.

PP: My friendship with Nottapon Boonprakob is what led to the birth of Conversation with the Sun. His mother and my mother have a mutual friend, and there was this one time he shared an interview of mine on his social media platform, and I’d always admired his story-telling style, so we started talking and became friends.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s film, Memoria, was going to premiere at a festival at the time, and we both bought tickets to see it together. Then we went to lunch, and we would occasionally send Apichatpong stories via email. One of them was when we utilized artificial intelligence to generate a conversation between him and Salvador Dali, and he thought it was very interesting and recommended that we explore this further together and see what we can do with it. That was before the enormous popularity of ChatGPT.

AI helps make these impossible conversations possible. Apichatpong told me that one of his inspirations as a kid was to be able to see the sun. To him, the light streaming through the window was cinema—the playing with light. ‘Why don’t we try to generate a conversation between me and the sun?’ he said. And he was also curious about what an artistic creation that was devoid of the artist’s ego would be like. Would employing AI to create conversations such as this make artists less egotistical? There are a number of questions that were brought up between us during this experiment.

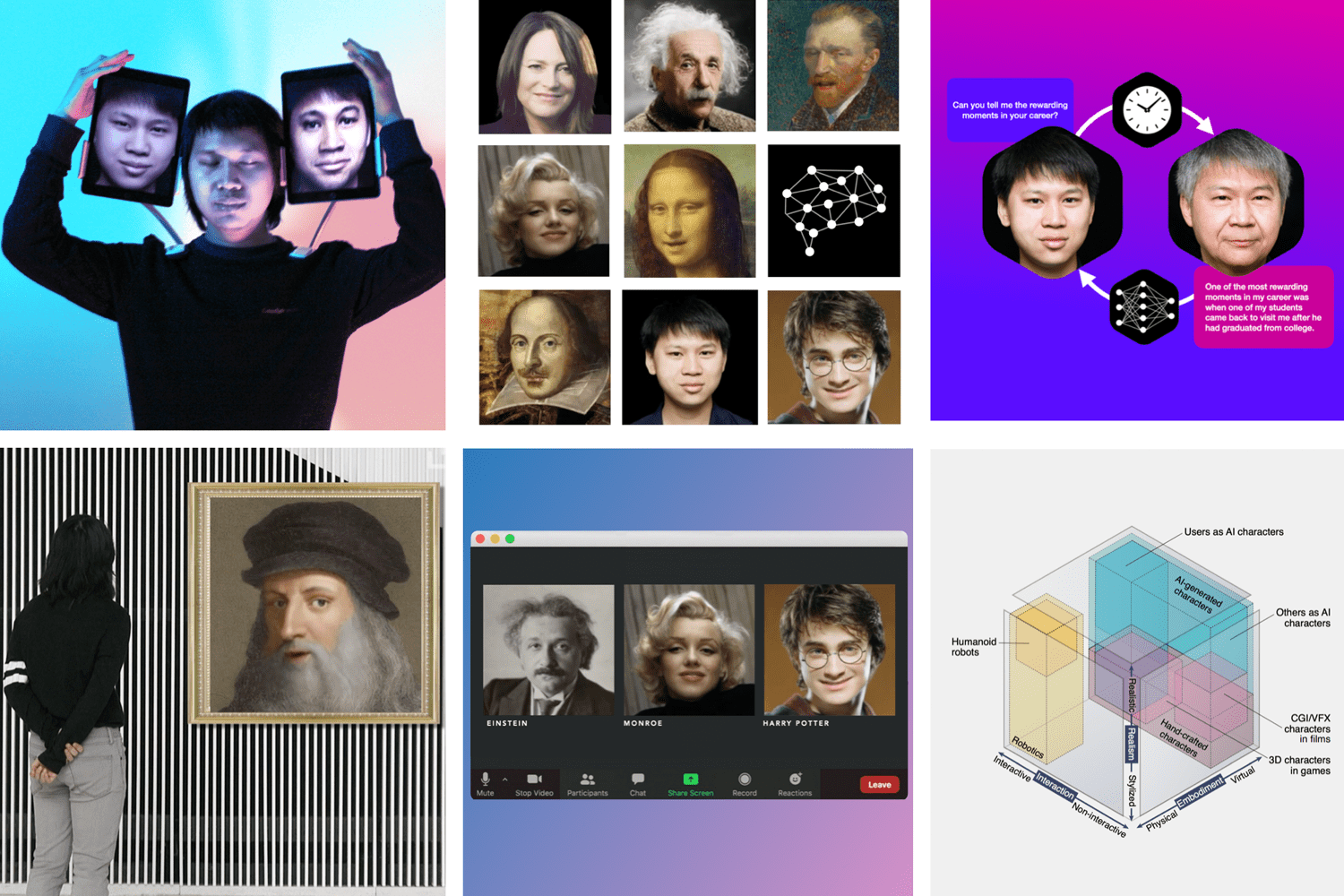

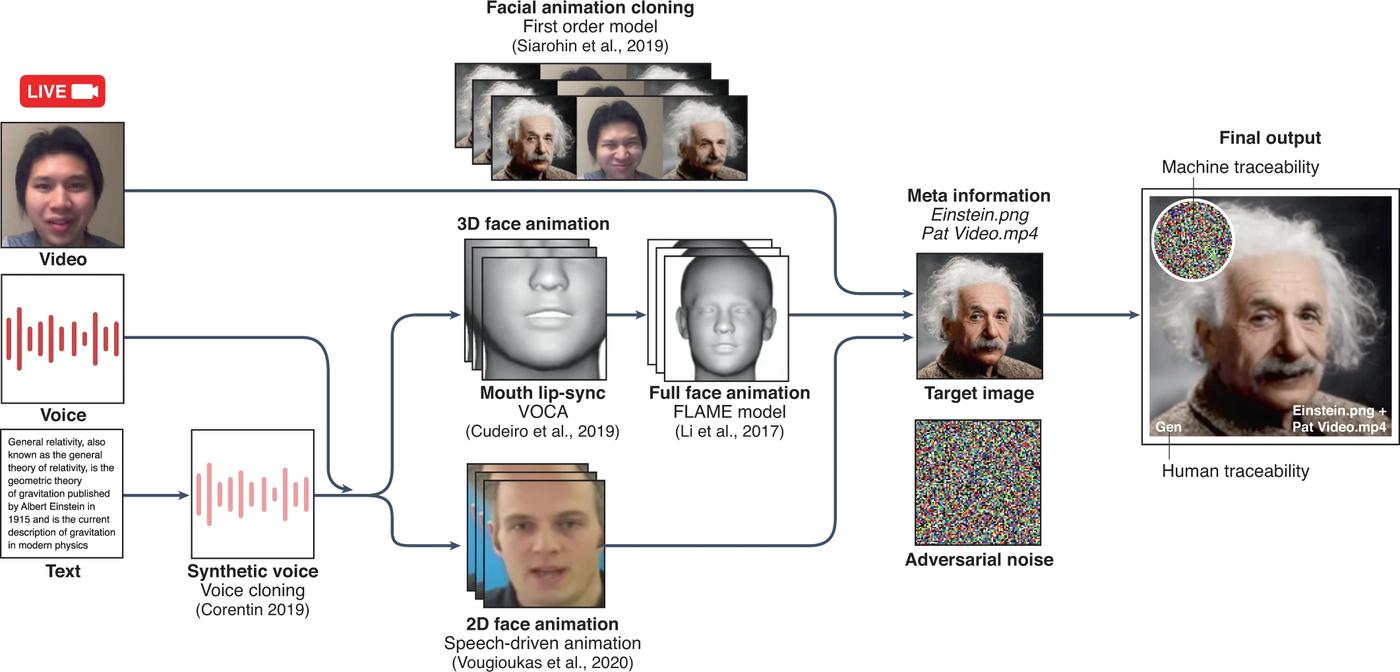

‘AI-generated Characters for Learning and Wellbeing’ | Image courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

art4d: Do you have a favorite literary genre?

PP: I like the classics. Works like The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury, Foundation, and Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton.

Science fiction, in my opinion, presents both possibilities and concerns. However, the most frightening aspects of technology are those that do not appear in science fiction. Fiction reminds us to strive to grasp certain human conditions. Nevertheless, the genuine problems with AI may not be something like the Terminator taking over the world, because if such a robot existed and acted in such a way, humans would kill it immediately (laugh). The scariest AI is the subtle AI, such as the AI that continuously feeds misinformation or fake news, inciting extremist beliefs that finally lead to people harming each other. That, in my opinion, is far more dangerous.

‘Machinoia: Machine of Multiple Me’ | Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

‘Machinoia: Machine of Multiple Me’ | Image courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

art4d: Do you have any advice for Thai students or those who want to follow in your footsteps in the future?

PP: Do not follow in my footsteps. Everyone is charting their own course. But if you like dinosaurs as much as I do, then yeah, follow me (laugh). I think the world is becoming more open with each passing year and that there is limitless potential to do something really powerful.

There are more times than one can count where people want to do something that they think is going to change the world for the better, whether it is improving the economy or making specific things smarter or faster, but they fail to consider how all of these things are interconnected. You might solve one problem while simultaneously causing another. Understanding philosophy, diverse points of view, and how everything is interwoven, I believe, is what the future world will be about. The ability to view different challenges through all kinds of stories is the most magical ability of mankind. Don’t be too extreme with anything. Try looking at things even if you don’t agree with them. Try to get to the bottom of things and figure out what’s going on. Having that ability to understand is going to be critically important in the future we’re heading towards.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

media.mit.edu/groups/fluid-interfaces

academy.cea.or.th

facebook.com/CreativitiesUnfold

Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn

Photo courtesy of Pat Pataranutaporn