INVITE EVERY OUTSIDERS TO DISCUSS THE FILM THAT ATTEMPTS TO PRESENT AN ‘OUTSIDER’ PERSPECTIVE IN THE BRUTALIST

TEXT: TIWAT KLEAWPATINON

PHOTO COURTESY OF A24

(For Thai, press here)

The momentum behind The Brutalist (2024) shows no signs of waning. The latest offering from the rising indie powerhouse A24 has swept up accolades, earning 10 Academy Award nominations and securing three wins—Best Actor, Best Cinematography, and Best Original Score. Despite its formidable 3-hour-and-35-minute runtime, which includes a 15-minute intermission, the film is a striking cinematic experience. It deftly straddles the line between art-house introspection—laden with singular, thought-provoking symbolism—and grand-scale spectacle, its sweeping camerawork and evocative score lending it a rare, immersive power.

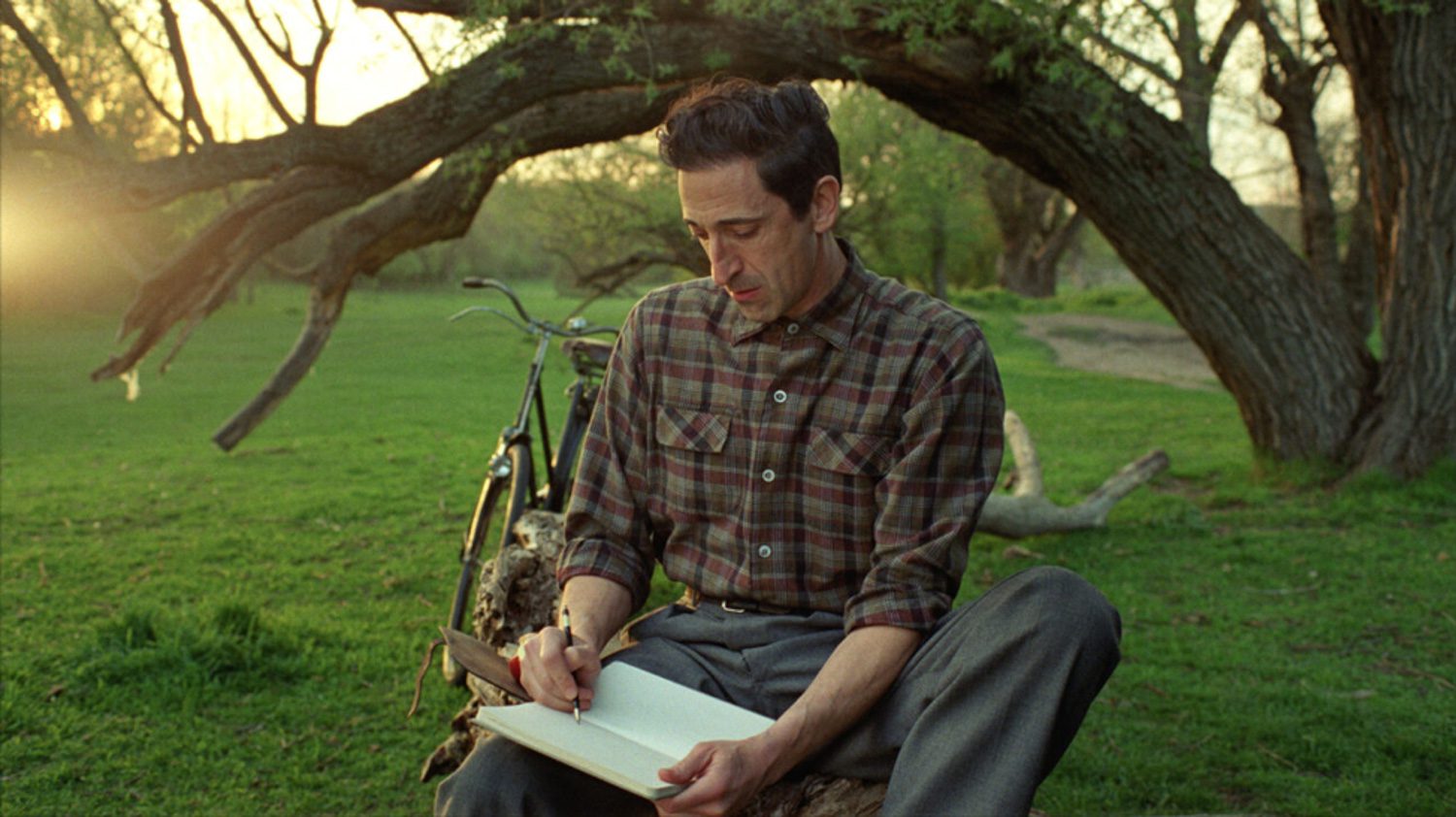

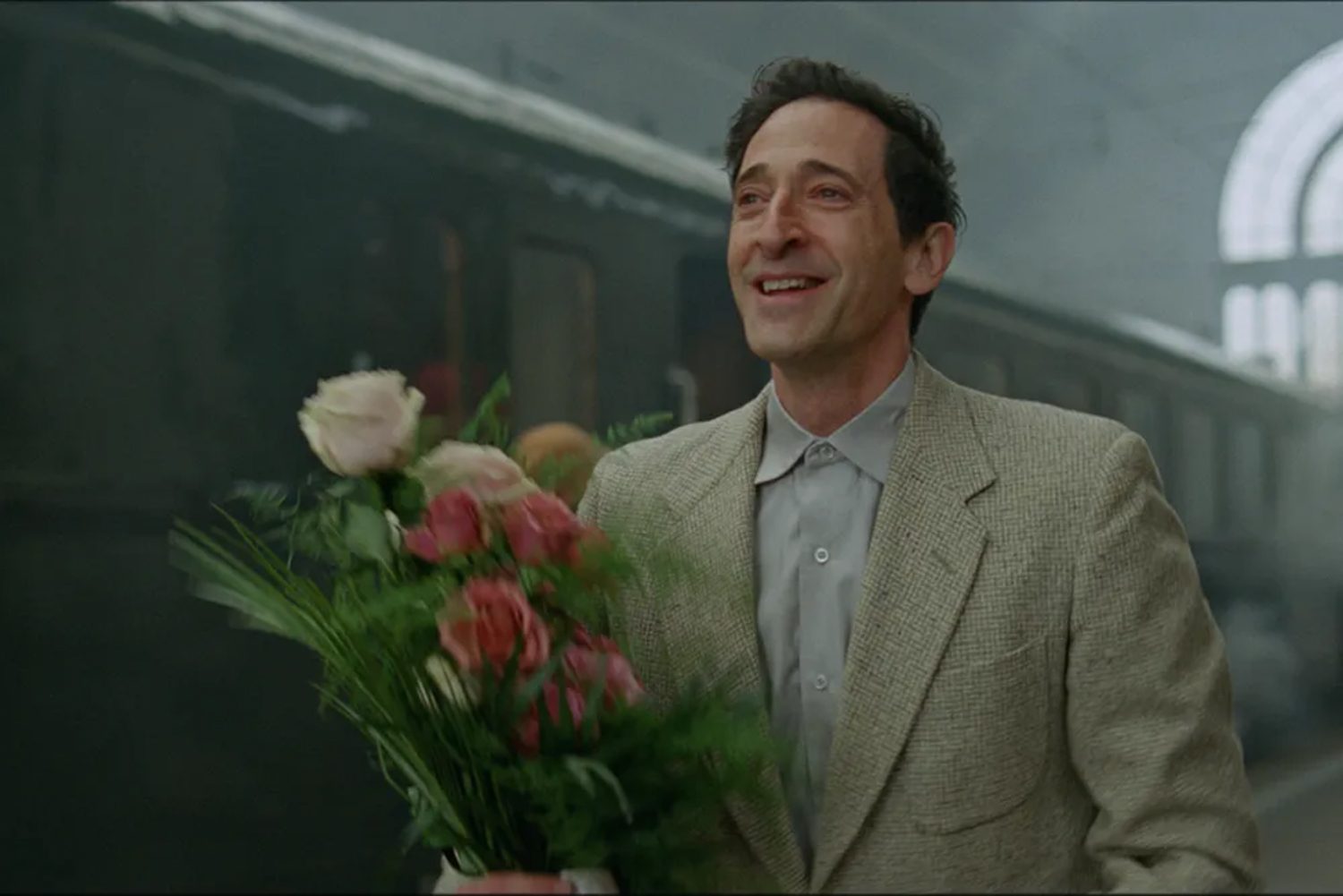

At its center is the Hungarian-Jewish architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp who, in the aftermath of World War II, immigrates to the United States in pursuit of a new life. His journey, however, is one of exile as much as aspiration since he was forced to leave behind his family, including his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), without knowing whether they had survived.

At its core, the film presents the perspective of an outsider struggling to carve out a place in America, driven by a belief in the American Dream, in the promise of opportunity, and in the ideals of a free world. Yet reality proves far more unforgiving. The United States of the 1950s remains deeply entrenched in systemic discrimination and racial prejudice. No matter how esteemed László Tóth’s architectural work had been in Europe, in America, he finds himself in a constant battle—not merely to be recognized for his talent but to transcend the label of ‘Jewish architect’ in a society that resists his presence. With relentless perseverance, he is forced to prove himself time and time again.

What sets Tóth apart from an ordinary immigrant, in our view, is that despite the relentless struggle to survive in America, he never loses his sense of self. He remains steadfast in his principles and beliefs, which are expressed unmistakably through his words, actions, and architectural work—deeply rooted in the ethos of Brutalism.

A brief note on Brutalist architecture: In the aftermath of World War II, as cities lay in ruins and entire neighborhoods were reduced to rubble, the urgency of urban reconstruction demanded speed and efficiency. Brutalism emerged from architects’ efforts to strip buildings down to their essence, eliminating all unnecessary ornamentation. The resulting structures were raw, unembellished, and often monolithic, with exposed concrete—an inexpensive, practical material—serving as the dominant medium. Brutalist buildings became a subject of intense debate: some lauded them as strikingly modern and forward-thinking, while others dismissed them as hulking, unsightly monstrosities that blighted the urban landscape.

Tóth’s unwavering commitment to his vision often put him at odds with his peers and the communities in which he worked. He faced persistent criticism, yet he never wavered in his convictions. In stark contrast stood his cousin, Attila, who readily conformed to societal expectations—changing his name, his religion, and whatever else was necessary to assimilate.

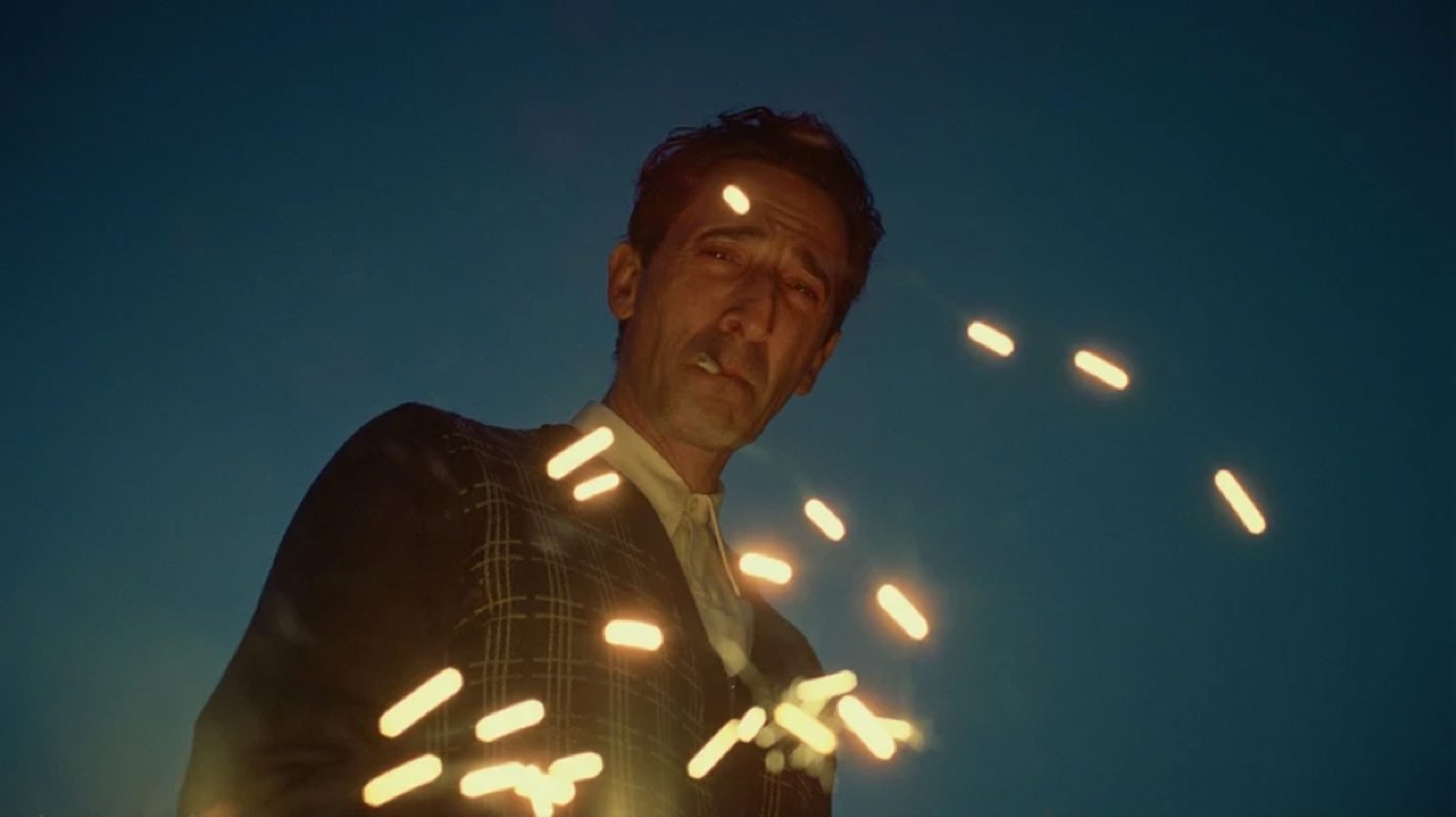

For us, this is the most compelling aspect of the film—the struggle not only against society and the surrounding culture but also against oneself in an effort to preserve the very core of one’s identity. It mirrors the architecture Tóth designs. Even with the backing of his patron, Harrison Lee Van Buren (played by Guy Pearce), Tóth remains locked in an ongoing internal battle. At what point does one compromise? The thin line between being obstinate and staying true to oneself is never entirely clear on the path of creation.

Beyond its thought-provoking narrative, The Brutalist also delivers one of Adrien Brody’s finest performances—a true masterclass not to be missed. The film’s production design is nothing short of breathtaking, particularly for those who appreciate architecture, with its striking Brutalist structures, exquisite cinematography, and an evocative score—both of which have been rightfully recognized with Academy Awards.

Finally, we can’t help but recall what director Brady Corbet said upon accepting the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Drama: “I was told that this film was un-distributable. I was told that no one would come out and see it. I was told the film wouldn’t work. But in the end, it worked.” It may sound like a familiar refrain, but in many ways, it echoes Tóth himself—an architect unwavering in his vision, standing firm until his work speaks for itself, just as this film ultimately has.