FROM PUBLIC BUILDINGS TO PRIVATE RESIDENCES, THIS art4d SPECIAL FEATURE WILL TAKE YOU TO WHERE THE ONCE-OVERLOOKED ARCHITECTURAL MOVEMENT OF THE 70S WILL UNFOLD BEFORE THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER.

During the 1960s, ‘New Brutalism’ appeared to be the key architectural discourse used to explain the architectural phenomena of the transitional period of Post-War Modernist Architecture. England, in particular, was where the long realm of modern architecture was questioned by young architects, architectural theorists and art historians. It led to changes in the Modernist Architectural movement from narrow aspects such as construction materials, which highlighted the use of local materials in an attempt to return to architectural forms that were reflections of their localities, to a broader sense where they began to realize that universality might not be able to answer all contemporary questions encompassing contexts ranging from culture to community or aspects of sociology, humanism and history (the influences from New Humanism and New Empiricism became more substantial among academics in that period). Such realization ultimately led the architectural academics to rethink and reinterpret these issues.

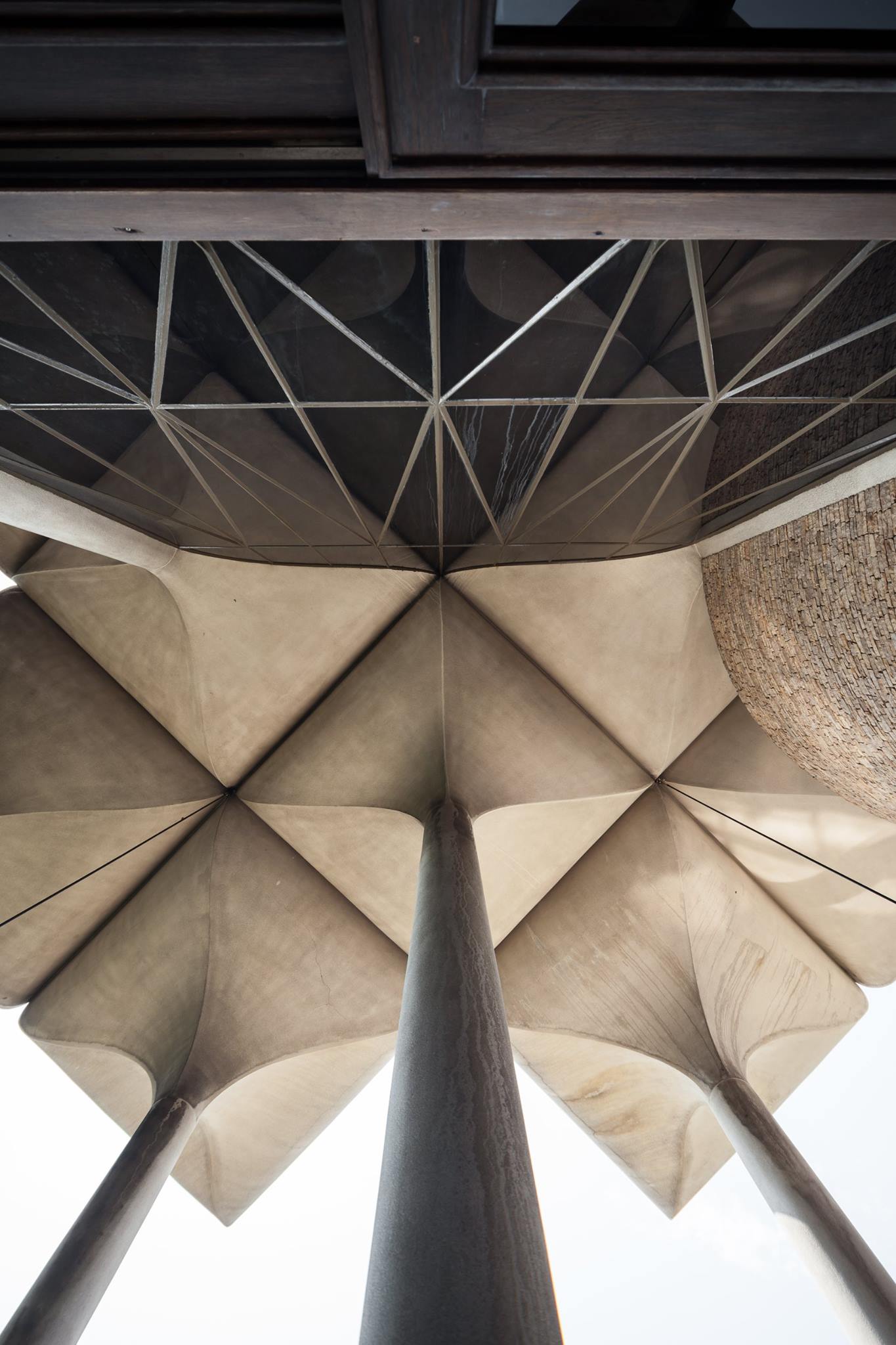

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The word “New Brutalism” (nybrutalism in Swedish) was first used in 1956 by Hans Asplund to explain the architecture of Villa Goth designed by Bengt Edman and Lennard Holm back in 1949. The house bears modernist characteristics whose construction has brickwork as the key architectural element where the design integrates raw materials with the notion of space according to modern architecture. It is where locality and nostalgic memories expressed through the use of materials found their place in architectural universality.

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Le Corbusier’s design and ideas for ‘Béton brut’ is a work where exposed concrete is utilized to express the rawness and truth of form and materials’ surfaces. His other works such as Unité d’habitation (1952) in Marseille, France and Palace of Assembly (1955) at Chandigarh, India or Maisons Jaoul (1956) in Paris, whose combined aesthetic of a curved concrete structure and brick wall made it one of the first ideas in the pioneering days of New Brutalism, have had tremendous impacts on modern architecture in later periods. In Bangkok, the emergence of New Brutalism architecture took place between the 1960s and 1970s. It was a time when the country’s development took place under American influence during the Cold War. Traditional architectural education from École des beaux-arts was questioned by new generation educators. It was a time when architecture students (those who were not the descendants of the country’s upper class) traveled abroad to pursue their studies before returning home to work as professional architects. The growth and expansion of the local economy (under America’s support) resulted in increasing demands for spaces that would accommodate new activities that the country had never seen, be they residential, religious or institutional buildings as well as modern office spaces.

The five buildings in Bangkok featured in this article encapsulate the New Brutalism mentality and can be divided into the following categories:

Apartment building – Siri Apartment (1970) (originally named ‘Kasemsan Mansion”) designed by Dan Wongprasat. Institutional building – the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office) (1972, 1987) designed by Angelo Pastore and Gianni Siciliano of Interproject in collaboration with Sittart Thachalupat, an architect from the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand. Religious building – The Foundation of Islamic Centre of Thailand (1971) designed by Paichit Pongpanluk. Residential building- Three-column House (1975) by Nitt Charusorn and Boonnumsup House by Rangsan Torsuwan. All of these buildings have concrete as the principle element with the material’s potential declared in the form of architectural creations and artisanal excellence that are intrinsically brutal and almost limitless.

Siri Apartment (1970) by Dan Wongprasat

Siri Apartment, 1970 by Dan Wongprasat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

From the original name Kasemsan Mansion to Siri Apartment, the building is now under the management of Plus Property Company Limited. Its architecture reminds many of a giant brown octopus. Some say it looks like a spaceship from a sci-fi movie or a bizarre looking household item from the 60s. The original idea behind the eccentric form of the building is basically a circle, Dan Wongprasat’s favorite shape, which appeared in many of the buildings he designed throughout his architectural career such as Ambassador Sukhumvit, Holiday Inn Silom or his own home.

Nonetheless, that is not the only reason why the architecture of Siri Apartment looks the way it does. Dan is an architect who gives high regard to climatic conditions, and his architecture is often derived from its surrounding local climate as well as the idea of tropical architecture. The building with its circular floor plan hosts a massive void that maximizes the ventilation of every floor. This very same void provides an abundant amount of natural light within each unit. Parts of the building are set back to prevent the interior from being directly exposed to sunlight, automatically creating an outdoor living area in the form of a terrace. The circular plan also grants every unit equal access to the outside view.

Siri Apartment, 1970 by Dan Wongprasat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Surrounding the plan are 12 cylindrical structures, each containing the functionality of a lift and stair core, some of which are restrooms and others kitchens. The rooftop areas of these compositions are where the water tanks are installed.

By separating the service cores from the main functional area, Siri Apartment reminds us of many of Louis Kahn’s buildings. Kahn was also Dan’s professor at the University of Pennsylvania, so this particular piece of Dan’s architectural creation could be, more or less, influenced by the aesthetics of his teacher.

Siri Apartment, 1970 by Dan Wongprasat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The exposed aggregate finish of the building’s exterior offers great durability without the need for regular repainting. Dan is the type of architect who prefers to showcase the materials’ true nature than cover them with paint, which explains why most of the buildings he designs are primarily exposed concrete architectures.

Siri Apartment, 1970 by Dan Wongprasat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The Foundation of the Islamic Centre of Thailand (1971) by Paichit Pongpanluk

The Foundation of Islamic Centre of Thailand, 1971 by Paichit Pongpanluk. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Paichit Pongpanluk designed the building being fully aware of its limited budget. He began by figuring out a way to incorporate a modular system while finding the solutions in modern architecture that could be applied to the design of the building where interesting architectural characteristics reflected contemporary construction technologies.

The result was a series of connected hexagonal plans that covered all the required functional demands and spaces. Each hexagon was designed to be 12-meters wide with a total number of 19 modules. The thin concrete shell of each module was constructed on the site with a column in the middle. The shape is reminiscent of a flower with six blooming petals while hidden in each column is a pipe used for draining rainwater from the roof.

The Foundation of Islamic Centre of Thailand, 1971 by Paichit Pongpanluk. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The continuity of the main functional spaces, which link the entire upper floor to the project’s main entrance, is one of the priorities of the design. Paichit situated a big hall in the middle of the program to function as the interface of the spaces created for male and female members of the congregation. These spaces are where religious activities and ceremonies take place and can accommodate approximately 5,000 people. It is located to the left and is designed to be in spatial unison with the hexagonal-shaped meeting room, which can host a maximum of 25 attendees (and 20 observers).

A pair of stair cores connects the ground floor, the hall on the upper floor and the area that female members use for their religious activities on the mezzanine into one continual flow. The ground floor houses a large meeting room with a maximum capacity of 1,000 people, the foundation’s office, a people’s library, book center (visible from the entrance hall), a broadcasting studio for radio broadcast and a function room.

The Foundation of Islamic Centre of Thailand, 1971 by Paichit Pongpanluk. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Another distinctive feature of this religious building is its Moresque (Moorish) and Arabian motifs on the walls including the beautiful presence of stain glass and carved Arabic verses from the Quran on 21 black marble slabs installed to face the Qibla direction. A small, local contractor was hired for the project while most of the workmen were members from surrounding neighborhoods whose expertise in concrete work was considered of a high quality at the time.

The Foundation of Islamic Centre of Thailand, 1971 by Paichit Pongpanluk. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office) (1972, 1987) by Angelo Pastore and Gianni Siciliano of Interproject in collaboration with Sittart Thachalupat, an architect from the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand.

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The project began as a collaboration between Interproject, a team of architects from Rome led by Angelo Pastore, Gianni Siciliano and Sittart Thachalupat, the project architect from the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand. The primary drawing took two months to be completed in Rome before it was sent to Bangkok where the design and working drawing were finalized and used for the construction.

The Head Office building of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand is comprised of five sets of circular cores. The interior space accommodates the presence of an elevator and a staircase, which serve as the vertical core that links and expands the main circulation in the horizontal axis. Sittart Thachalupat, the project architect explains the idea behind the design concept of the building, “We agreed on the use of a circular core because its perceivable cylindrical form creates an interesting gimmick and a distinctive shape. You can imagine the interior space by looking at the building’s exterior structure, which makes the design even more special while the functionalities are all there as required.” Sittart believes that a good architecture is the one whose form reflects the interior characteristics.

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Since the progress of the project was determined by the annual budget it received, the building, therefore, expanded horizontally in order for the space to be better managed during ongoing construction. The addition of the structure was completed floor by floor, from 4 to 5 to 7. From the outside, the cluster of buildings seems physically continuous and connected. The concrete laths used with the roof welcome in natural light to the communal hall and walkways on each floor. The exposed concrete and extruding beam structure were the results of the architects’ intention to exhibit the location and size of the beams as the building’s key architectural elements as well as display the material’s true nature.

The horizontal addition of the structure, which was completed in 1987, was complemented by the 15-storey high building and a parking space located to the back of the program. The central core is comprised of three sets of concrete structures, which were located to suit the physical condition of the land. Glass was used for the outer shell to embrace natural light since the orientation faces this particular side of the building towards the north. The project employed construction technology from Doka, a concrete formwork expert from Germany. For the construction of the structure of each addition, the molds were elevated to reach the required height of each floor while casting was done without having to demolish and reassemble the molds. It was the most timesaving and progressive construction method at the time.

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Head Office), 1972, 1987, Sittart Thachalupat. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

Three-Column House (1975) by Nitt Charusorn

Three Column House, 1975 by Nitt Charusorn. Photos by Tonton

The first draft Nitt Charuson proposed to the engineer and the owner of Three-Column House- Jirawudh Vanasup, was a four-column structure. After a considerable exchange of opinions, both Nit and Jirawudh agreed that such structure could obstruct the view of his parents’ house (situated on the same piece of land). The final decision was to eliminate the column that would cause such obstruction. “Let’s build a house with three columns,” was what Jirawudh said to Nit 41 years ago as he immediately began sketching the load transfer of the new structure on a piece of paper for the architect to see.

The design process was a collaborative one. The two sat down, talked and exchanged ideas as the design was developed. The project took place in 1975 before the construction started in 1976 and it was not until 1981 that the house was complete and ready for the owner to move in.

Three Column House, 1975 by Nitt Charusorn. Photos by Tonton

“I used a computer. It was a program I developed myself. I rented an IMB 360 at IBM Centre in Saladaeng and used the program that I wrote to work on the design. I remember using Fortran as the programming language, following the flow chart created by a professor from Stanford University. I think it was the first house in Thailand that used a computer for structural calculation,” recalled Jirawudh regarding the engineering method employed for the design of the house.

Three Column House, 1975 by Nitt Charusorn. Photos by Tonton

“For the concrete casting of the house’s structure, the mold was made of Tabak wood and the whole thing was put together using wedges (the mold was used for the entire construction) and the inside was clad with plywood before coating it with diesel oil. We changed the plywood after the mold was used twice. The concrete we used was CPAC ready-mix concrete from the factory.

The engineer who was overseeing the construction of the house, we called him by his nickname, ‘Hem.’ He’s Nitt’s friend. They knew each other when they were both working at EGAT and he was a real expert in concrete work. His daily rate was 300 baht, which was very expensive back then.”

Since the span of the beam structure designed to maximize load transfer is quite large, the house’s interior space naturally becomes very open and highly flexible. The second floor was originally a multi-purpose area but with two new members added to the family, the space was later readjusted to host two bedrooms.

It has been 35 years and now the empty land to the back of Three-Column House is where the construction of the children’s new house is taking place. Once the new house is finished, Jirawudh thinks that it will be time to tear down the walls of the kids’ bedrooms and turn the second floor of the Three-Column House back into the multi-purpose space it was meant to be.

Three Column House, 1975 by Nitt Charusorn. Photos by Tonton

Boonnumsup House (1979) by Rangsan Torsuwan

Boonnumsup House, 1979 by Rangsan Torsuwan. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The brief given from Boonnum Boonnumsup, the house’s owner was for a house with a spacious residential area that could accommodate guests and a little gathering. The design had to be unique, with no presence of a hip roof whatsoever.

At the particular time, Rangsan Torsuwan was working on the design of several branches of Kasikorn Bank. His work brought incredible success to the organization, which was attempting to use architecture as a tool to recreate its organizational identity. With the task being to design a house that had to be ‘unique and one of a kind,’ Rangsan did what he knew best and employed the very same architectural technique he used with the bank for the birth of Boonnumsup House.

The result was a house of a muscular and robust structure where delicate and majestic lines and details are present.

The rectangular summit of the structure gradually descends and transforms into curves before smoothly unifying into columns. Many said that the design mimics the shape of a tree, some said a wine glass, but Rangsun named his series of structural systems ‘marble.’

Boonnumsup House, 1979 by Rangsan Torsuwan. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The structural system of ‘marble’ encircles the house and serves as the key element that contributes to its unique features. The entrance hall was designed to be wide open, with a glass wall that runs from the floor to the bottom of the house’s upper structure. Another structure system was used for the interior space where normal roofing was installed to prevent future leakage. Pipes were hidden in the columns to help drain the rainwater from the roof.

Boonnumsup House, 1979 by Rangsan Torsuwan. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

The construction was handled by a contractor known as ‘Ko Ngeab’ whose great expertise in concrete work Rangsun vouched for. Several sets of molds were created using a very complicated technique and the price of wood was rather expensive. The exterior wall’s exposed aggregated finish was the work of a reputable artisan named ‘Yong.’ His passion for the craft is reflected in the work he created and the choice of materials he chose such as the imported lime concrete made of seashells he preferred over the Thai one, which was made of burnt limestone.

In Rangsun’s view, to construct this type of architecture in the contemporary time period can be incredibly challenging since it is now too hard to find a contractor of such high level of expertise.

Boonnumsup House, 1979 by Rangsan Torsuwan. Photo by Ketsiree Wongwan

TEXT: WICHIT HORYINGSAWAD