SUMANATSYA VOHARN WALKS US THROUGH ‘WHICH ONE?,’ THE LATEST EXHIBITION HELD AT TCDC CHIANG MAI THAT KICKED OFF DURING THE CHIANG MAI DESIGN WEEK 2019, AND GIVES US HER VIEW ON THE VALUE OF EVERYDAY OBJECTS WE USUALLY FIND AT THE LOCAL MARKET

TEXT: SUMANATSYA VOHARN

PHOTO COURTESY OF TCDC CHIANG MAI

(For Thai, press here)

The issue revolving around our instinct to critically question and discuss the definition of locality and the inspirations behind creativity begins with the conversation that opens the exhibition. It is seen through the point of view of Chatpong Chuenrudeemol, architect and founder of CHAT architects who is currently working on his personal research, BANGKOK BASTARDS, and Professor Nussara Tiengkate, the former social welfare worker who has spent that past 20 years of her life developing local handicrafts in Chiang Mai as an expert in local crafts and textile.

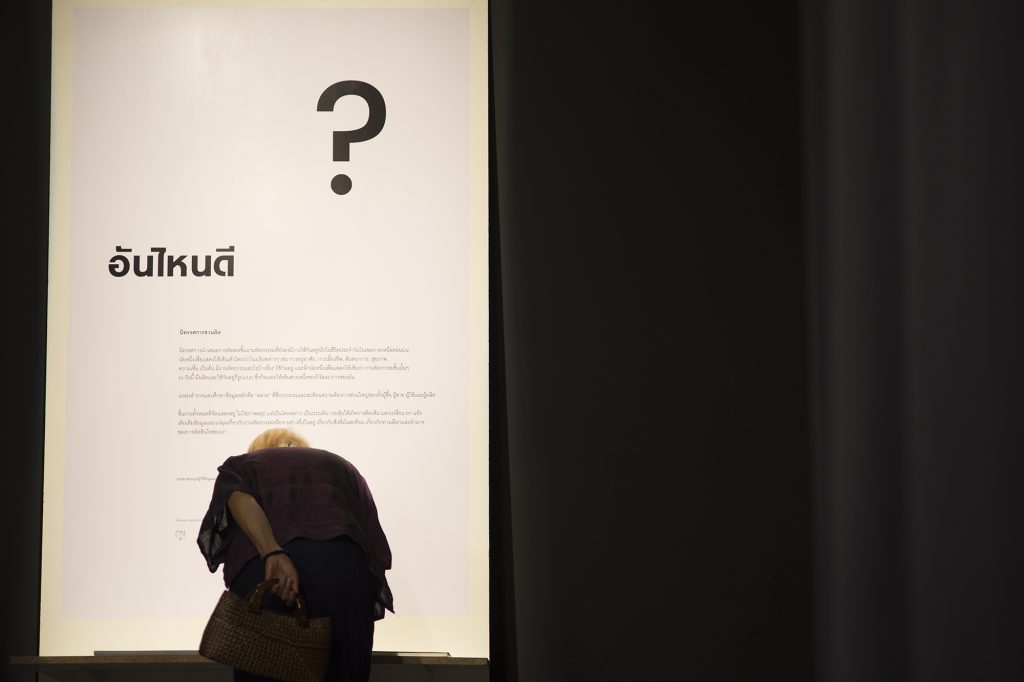

The large door with many question marks on it at the front entrance of TCDC Chiang Mai stimulates viewers’ curiosity and anticipation of what they are about to see before actually entering the exhibition space. The one-meter wide walkway is partitioned with a large black curtain as viewers must make a decision to enter either through the left or the right entry. A green plastic doormat with the word welcome on it is placed in front of the left entrance, while the right entrance has a familiar-looking doormat made out of coconut fiber.

As we passed through one of the entrances, we came across different local household objects such as a chicken coop, sticky rice containers of various sizes, animal traps, tools invented and used by local handymen as so on. Showcased on large display islands, each of the objects were presented with a distinctively visible price tag and a poetic description written in both Thai and the local language. Written in long and short dialogues, these descriptions makes one wonder about the back stories behind each of the items that were being exhibited as the curator took us back to revisit the connections between the buyers, sellers, creators, and users of such articles, inviting but not dictating viewers to think about the societal and living conditions of the people back in time when the journey of finding these items took place.

In places outside of Thailand, most design-related exhibitions that showcase special aspects of everyday life objects are often curated either by curators or designers whose definitions of ‘ordinariness’ are proposed for viewers to contemplate in greater detail. Some of the examples are ‘Super Normal’ and ‘The Hard Life’ that has Jasper Morrison as the curator, as well as ‘The Boundary Between Kogei and Design’ which is curated by Naoto Fukasawa, leading viewers to ponder the evolution of everyday objects, from handicraft items to design creations.

For Thailand, such curatorial approaches are often employed mostly by folk museums such as Ja Thawee Folk Museum, which recounts Phitsanulok’s local way of life through a rather straightforward presentation. This is often the case mainly because of the norm and perception where spaces in museums or exhibitions are preserved only for the objects of certain social statuses. For this exhibition, Sarngsan na Soonthorn takes a different approach by curating the objects with the concept of a ‘market’.

This explains the plastic price tags which are hung from the displayed items. The exhibition’s narrative intertwines these objects to the actual commercial activities of local markets in the northern part of Thailand. In other words, the objects are linked to the historical spaces that are still quite active with several superimposed dimensions of local beliefs, cultures, traditions, recreational activities, living aesthetics and so on. The first and key question of the exhibition, ‘which one is good?’, leads to the comparison between the two exhibited objects or more, which share similar functionalities yet bear certain different details. Other curiosities from viewers ensue, asking other possible aspects of what is ‘good’—how is it good? Who is it good for? Who makes them? Who uses them? Who are the ones that make decisions about which object is good and which isn’t?

While the exhibition doesn’t provide any answers to these questions, the curator does present a clever way to take viewers back to the root from which ideas and processes of these craft products originated. Divided into three stages, the first stage looked into the origin of crafts as a result of human’s survival instinct that led to an attempt to come up with solutions to overcome limitations. The second stage revolved around the aspect of comfort, expression of social status and appreciation in the aesthetics of the created objects. The third stage is the contemplation of objects using one’s personal anecdotes, wisdom, and the nature’s ultimate truth.

If what today’s society prioritizes is the development of local craft products to showcase styles, techniques, and commercial materiality, the exhibition may have opened a new door for one to alternatively look back into the origin of these objects as a result of human’s attempt to survive, the existence and changes of the objects that continue to ensue. It can ultimately end up bringing about many more open-ended questions from various points of view that will nurture plenty more processes of design thinking to come. It will also allow viewers of diverse backgrounds to take part in the search for the subjects and issues that will potentially emerge. Eventually, they will be able to look back at ordinary objects and the mechanism of ideas behind their genesis whose contribution to new developments are just as significant as the finished and seemingly ready-made products we usually see before our eyes.

The exhibition opens from 26th November 2019 to 1st March 2020.