KHAO YAI PRIVATE MEDITATION CENTRE, SITUATED IN EXPANSIVE FORESTED TERRAIN OF KHAO YAI, WAS EMERGED FROM THE QUESTION ‘ HOW TRADITIONAL THAI ARCHITECTURE COULD HARMONIZE WITH THE UNIVERSAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ARCHITECTURE ’

TEXT: KORRAKOT LORDKAM

PHOTO: W WORKSPACE EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

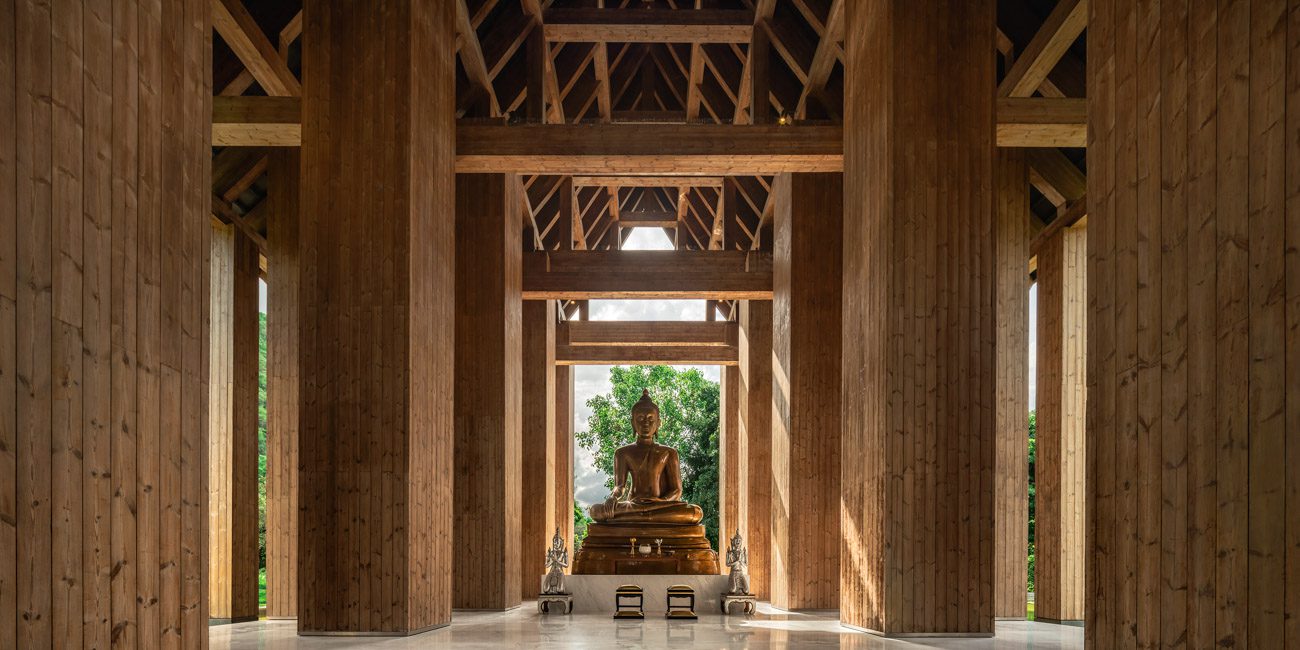

For a considerable period of time, Khao Yai’s expansive forested terrain has served as a popular destination for holidaymakers. However, it has also emerged as a prominent site for spiritual rejuvenation and religious pursuits, owing to the presence of numerous Buddhist monasteries and statues. The private meditation center that has DBALP (Duangrit Bunnag Architect Limited) behind its architectural design is one notable example. A tranquil meditation space tucked away in the midst of nature complements the project’s meticulously designed main hall, which is home to a magnificent Buddha statue. In addition to its architectural significance, this place holds immense religious value, following the intention of the family that is the owner of the project. Furthermore, its presence exemplifies the long-standing presence of Buddhism in Thailand with a contemporary architectural language.

This private practice is the personal establishment of a business professional and his extended family. The owner’s profound faith in Buddhism inspired the idea of creating a private space for dharma practice and religious activities, which eventually evolved into the design and construction of the private meditation center.

Initially, all completed buildings would be divided into different zones, such as the religious activity zone, the monk cells housing the monks, and the visitor accommodation zone. The first zone consists of the main hall, which houses a huge Buddha statue. Here, an outdoor courtyard is placed in the center, connected to and divided into other additional facilities, such as a library and a communal meditation room, which are located on the other side of the same building, with the cafeteria located on the opposite wing. All of these functional spaces are built separately from the zone where the ten monk cells are located. The cells are constructed around a newly excavated pond that serves as a basin during heavy rains.

Cafeteria Building

Cells for monks

A huge ground that is home to lodgings for dharma practitioners and visitors is situated further away, and divided into two female and male buildings, each with a capacity to accommodate up to 20 to 30 people. The project’s architect, Duangrit Bunnag, explained that everything was realized under the concept that built structures would seamlessly nestle into the lush landscape of a wonderful array of trees and plants. Meanwhile, the buildings’ exteriors are kept simple as boxy structures with flat roofs, in line with modern architectural ideals, with no need for further elements that might otherwise overwhelm the overall architectural language.

Dharma practitioners and visitors’ lodge

The box-shaped buildings exhibited a distinct architectural design that differed noticeably from the main hall, which played a major role in the overall project. The architect provided an interesting explanation regarding the design concept of the building.

“The primary goal of this project is to construct the main hall while deviating from the traditional Thai architectural style in its design. I sought to explore a fresh perspective on Thai architecture, unburdened by traditional constraints. My aim was to create a religious building that could be perceived, comprehended, and appreciated as such while also incorporating a universally appealing architectural language.”

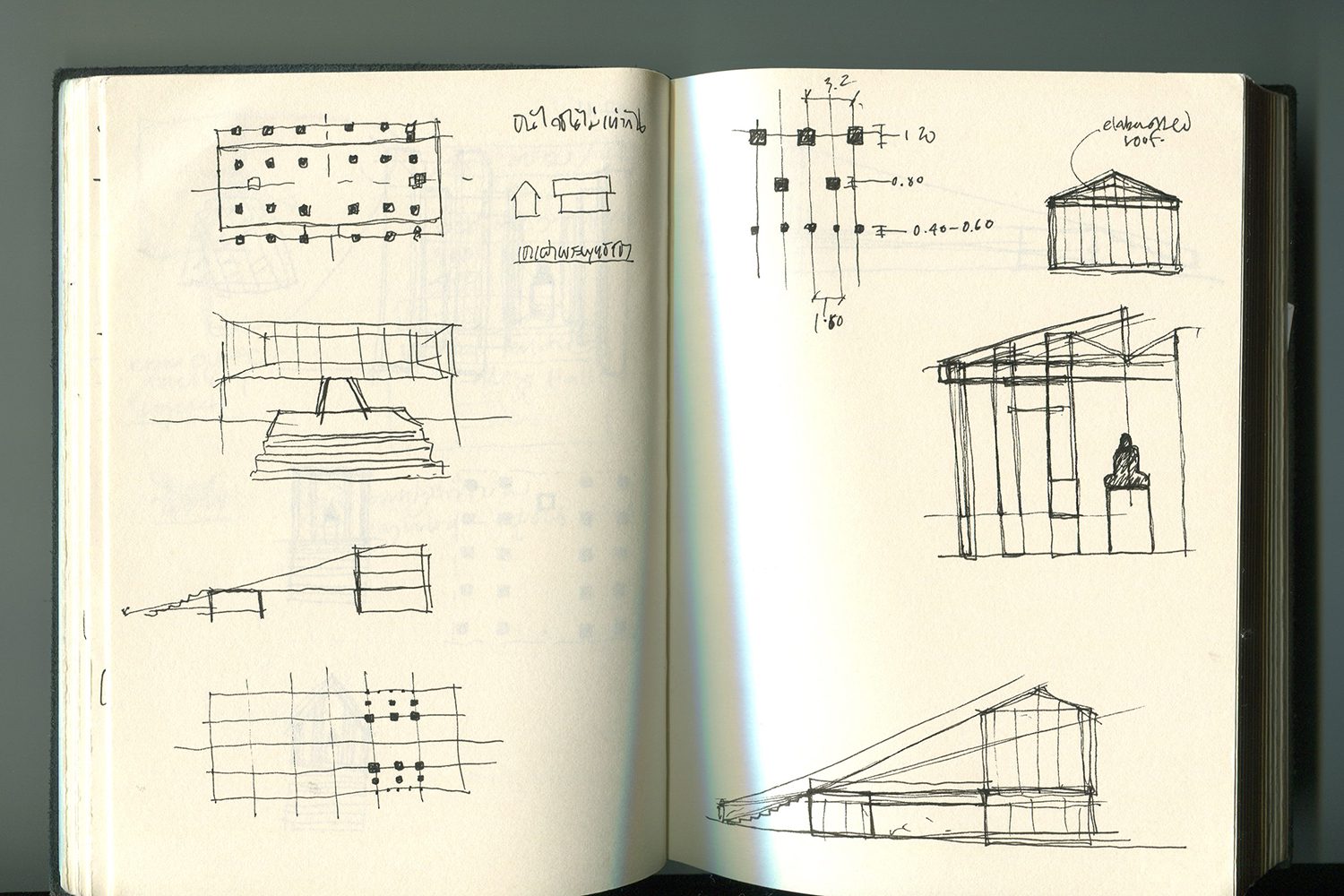

Duangrit mentioned that he discovered an approach to this novel style of religious architecture during his visit to Borobudur, a renowned Mahayana Buddhist temple and UNESCO World Heritage Site situated in Indonesia. The temple is adorned with inverted bell-shaped perforated stone stupas, which greatly enhance the site’s architectural grandeur and leave a lasting impression on visitors. Among these stupas, the details of their diamond-shaped perforations are particularly striking, further adding to the remarkable and powerful presence of the temple. Duangrit drew a comparison between the physical attributes of the stupas, where both openness and enclosure coexist, and the characteristics of glass. In his perspective, the convergence of perforation, openness, and enclosure represents an architectural attribute that bears resemblance to the transformative qualities of glass materials. This concept is something he intends to incorporate into the design of the religious structures for this particular project.

The main hall, which the architect designed with the intention of utilizing the aforementioned architectural language, houses a large principal Buddha statue. The initial design of the building was intended to incorporate the sizes, proportions, layout, and height of the main halls found in traditional Thai temples. As a result, the overall aesthetic closely resembles that of the main halls found in traditional Thai monasteries, something many individuals would find familiar. The design incorporates traditional architectural elements, such as a prominent gable roof and how a building can only be accessed through its two narrow sides rather than from all directions.

One notable feature that sets the design apart from typical main halls in Thai temples is the deliberate omission of walls and the utilization of columns to establish spatial enclosure. The design of the column is derived from the concept that was inspired by Borobudur. To provide additional clarification, the architect has designed the building in such a way that it consists of three rows of columns that overlap with one another. The intentional arrangement of the columns in alternating and overlapping positions at the outermost, middle, and innermost parts is intended to create a perspective in which all the columns collectively produce a visual effect reminiscent of the perforated stupas of Borobudur. The design replaces the walls’ complete enclosure with an openness with a sense of transparency similar to that offered by glass. It can be stated that the design has resulted in the creation of what the architect described as a “glass wall without real glass.”

Furthermore, the architect’s intention was to expose and articulate the intersecting structural elements by means of the open ceiling, thereby showcasing the way in which the superimposed structural members are interconnected. The entire structure is constructed using steel and covered with Swedish pine wood, 100% of which was sourced from Sweden’s sustainably managed forests. Furthermore, the wood underwent a manufacturing process that improved its long-term durability. The use of wood to encase the structural elements not only demonstrates the architect’s intention to incorporate environmentally friendly and responsibly sourced materials but also imparts a welcoming and friendly aesthetic to the building in general.

Despite the considerable size of the main hall, the design of the architecture aims to create a sense of relatability and accessibility, reflecting the architect’s vision for this specific religious structure.

“The main hall holds great personal significance for me as it has provided me with a valuable opportunity to delve deeper into the realm of Thai architecture, including works that are quintessential examples of Thai architecture. This experience allowed me to explore ways in which traditions can be in harmony with the universal characteristics of architecture. I sought to understand how elements that are inherently Thai can seamlessly integrate with the broader characteristics of architecture, going beyond mere superficial imitation. The objective of this main hall is to ensure that individuals won’t feel intimidated by its architectural design. Certainly, I wanted the building to embody the magnificence and refinement characteristic of religious structures constructed upon traditional principles and beliefs. However, I also aimed for it to exude an atmosphere of intimacy and humility—a space that individuals can connect with and approach easily, despite its remarkable presence.”

Photo courtesy of Duangrit Bunnag Architect Limited

Duangrit further recounted how the project provided him with an opportunity to delve into traditional Thai architecture and Buddhist philosophy, subjects he is personally interested in and have had a profound impact on his life. In the end, he compared the approach he adopted to design this unconventional piece of Thai architecture to a religious encounter. According to Duangrit, both architecture and Buddhism are vast bodies of knowledge that can be explored from various perspectives without being confined to a single method.

“To me, Buddhism encompasses an expansive and profound philosophical realm that can be approached from various angles. The architectural structures that I have designed for this particular project embody principles of balance, simplicity, grace, and tranquility. Upon entering the main hall, individuals will experience the serene and profound spiritual experience that is characteristic of Buddhism. While there is nothing excessively thrilling or extravagant about it, this is my personal interpretation of Buddhism, as seen through the lens of my own beliefs and perspectives. With this work, I, too, approached only a particular aspect of Buddhism, and this project is certainly not the definitive interpretation of the religion as a whole,” concluded Duangrit.