HAVE A LOOK AT A SERIES OF MODERN ARCHITECTURES IN SOUTH SUKHUMVIT, ALONG WITH AN OVERVIEW OF THE NEIGHBORHOOD AND THE HISTORY OF THE ARCHITECTURE IN A TOUR BY ART4D AND CREATIVE LAB BY MQDC

TEXT: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUK

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

The existence of True Digital Park and the emergence of Cloud 11 undoubtedly confirm that the southern part of Sukhumvit Road is destined to become a vital economic hub of Bangkok in the future. Simultaneously, the area, now increasingly referred to as ‘South Sukhumvit,’ is filled with an intriguing past, particularly concerning the stories revolving around modern architecture in Thailand, which is currently at a critical juncture in the face of impending changes brought about by the winds of urban development.

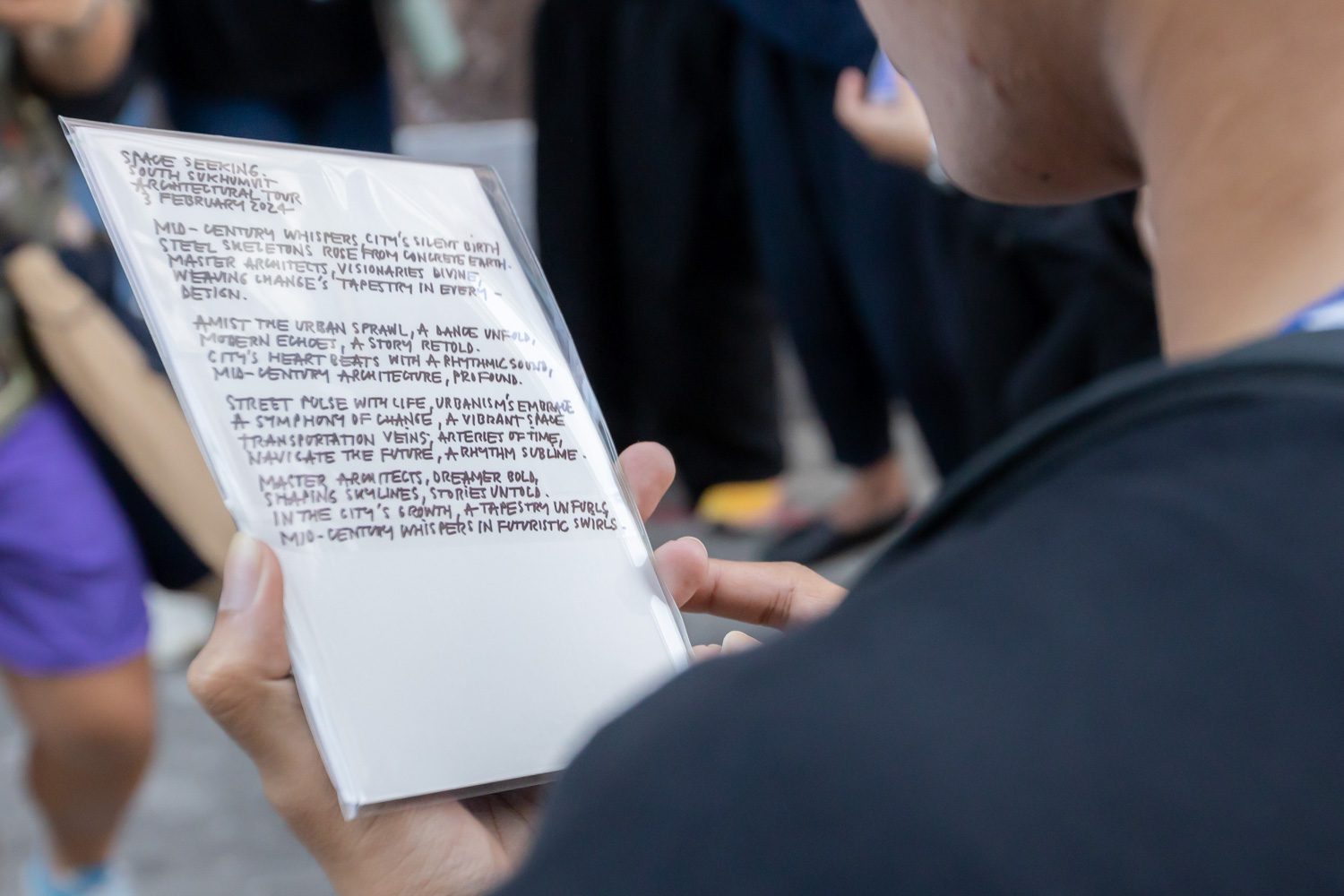

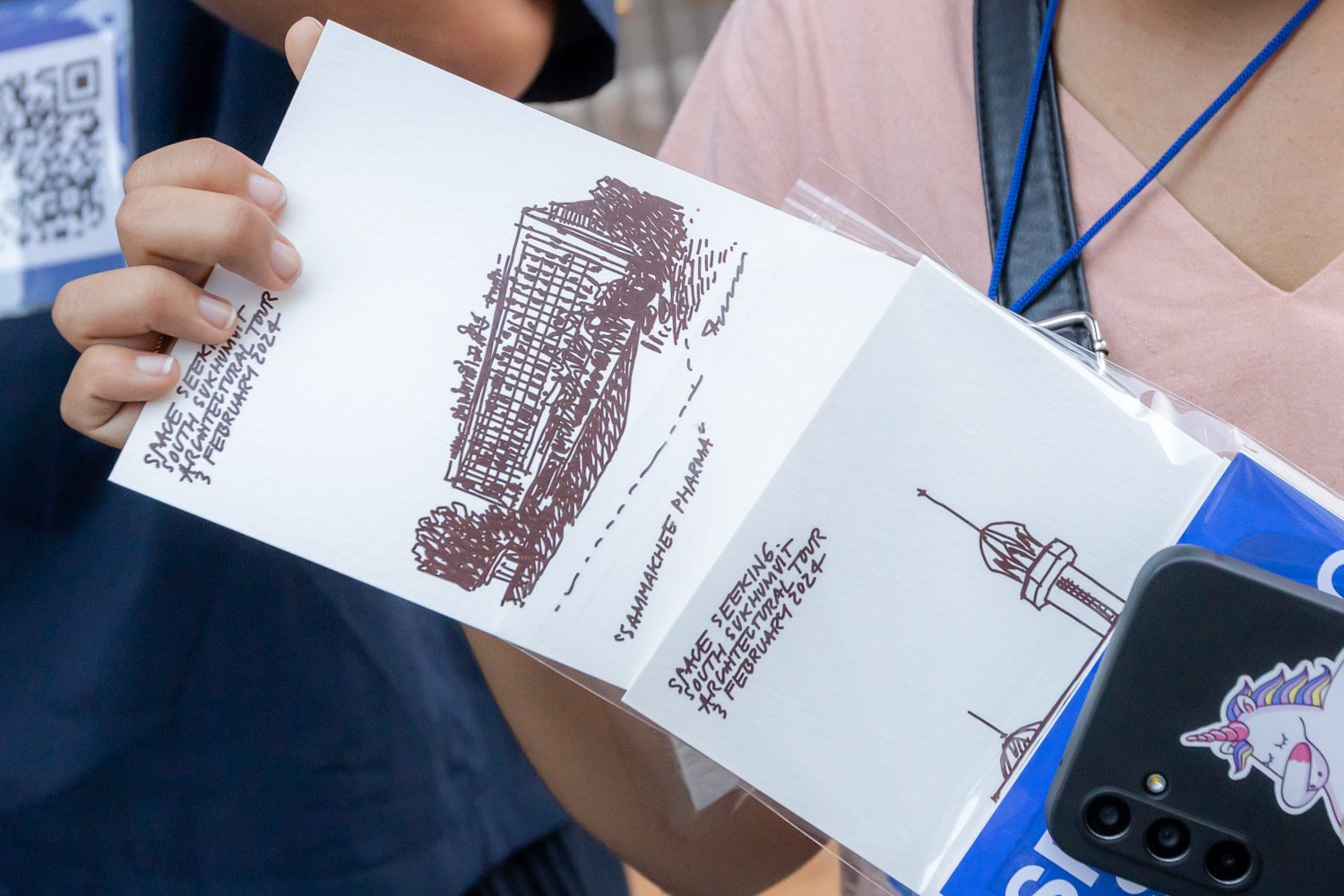

During the recent Bangkok Design Week, on February 3, art4d collaborated with Creative Lab from MQDC and Cloud 11 to organize the event ‘SPACE SEEKING – South Sukhumvit Architectural Tour.’ This project aimed to lead those interested in architecture and history on an exploration of modern architectural works in the South Sukhumvit area (covering districts from Phra Khanong to Bang Na). Weerapon Singnoi, an architectural photographer and the owner of the foto_momo page, carefully selected each and every building featured on the tour’s program. Joining the walk were speakers who are experts in the field of architecture and urban development, including Salyawate Prasertwitayakarn, an architect and founder of Atelier of Architects, along with Boonchai Tienwang, the Managing Director of Stonehenge.

Simply speaking, this project is an exploration driven by attentive consideration of the past because there is nothing more regrettable than losing a part of the past without ever knowing anything about it.

Upon the start of the tour, Salyawate and Boonchai gave a brief introduction at True Digital Park, laying the groundwork for participants to navigate the cityscape in a more engaging and knowledgeable manner. They gave a general overview of Bangkok before going into more detail about South Sukhumvit’s urban and architectural landscape. This included insights into population density, public transportation systems, green spaces, and other relevant aspects. The historical background of the area was also mentioned, encompassing the establishment of numerous pharmaceutical factories around 1967. This period marked a pivotal moment preceding the evolution of architecture in Thailand, extending from the mid-century era to the present day.

The introductory talk concluded by delving into the historical aspect and highlighting distinctive elements of modern architecture as well as prominent features of Brutalist architecture, such as façade designs and materials. The intention behind the introduction was to assist participants in connecting the past to the present, fostering a deeper understanding of the fundamental aspects associated with each of the buildings they were about to explore.

The first stop on the tour is the Phihalab Building (1960), which once served as both the office and pharmaceutical manufacturing facility for the Udomphon Company. Designed by Professor Dr. Ruangsak Kantabutra, the first Thai individual to study under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the structure stands out for its architectural efforts to adapt to Thailand’s climate. Such an endeavor is evident in the design of walkways surrounding the functional area and the incorporation of an additional façade layer on the exterior, which serves to protect against both rain and sunlight. The inner side of the façade was meticulously designed in a calculated sequence and constructed with aluminum, a rare building material at the time. This is particularly noteworthy as it distinguishes the building from others predominantly constructed from concrete.

Another distinctive feature of the building is its expansive drop-off area at the front, showcasing the waffle slab structure and highlighting the intersection of engineering prowess with aesthetic dimensions. While the tour did not delve into the interior details this time, the Phihalab Building has been periodically opened to the public, providing architectural enthusiasts with a closer look at its unique features. Collective by Cloud11, held last year, was among the events granted special access to explore this architectural gem.

Not far ahead, approximately 400 meters away, sits Kasikorn Bank’s Sukhumvit 101 Branch. What distinguishes this building is its inventive use of vertical concrete fins, strategically employed to offer shade to the upper section. The lower part of the structure, acting as the foundational support for the upper portion, showcases a distinctive column structure with branching elements that intricately interconnect. While Rangsan Torsuwan, a renowned Thai architect, designed over a hundred branches of Kasikorn Bank during that era, the vertical concrete fins on this particular branch deviate from his typical style. Both Salyawate and Boonchai speculated that this departure might be attributed to Colonel Chira Silpakanok, the architect responsible for the design of the iconic Indra Regent Hotel (1971) and Scala Cinema (1969), who had also designed a number of Kasikorn Bank branches during that specific time period.

In addition to the two previously mentioned buildings, the program also included a visit to the Union Drug Labs Building (1964), whose front façade is adorned with a large ‘Brise Soleil,’ a sun-shading screen meticulously arranged in a grid-like configuration. The route guided participants past the Pornchai Trading Building, where everyone took a brief moment to explore some of its intriguing features. Notably, the upper section of the building protrudes its façade outward, creating shaded space beneath the structure below (a reminiscence of the architecture of Boston City Hall).

However, the significance of the Phihalab Building, Kasikorn Bank’s Sukhumvit 101 Branch, and the Union Drug Labs Building goes beyond their representation of the mid-century design era in Thailand. They’re catalysts for historical dialogue reflecting the intriguing evolution from the decline of pharmaceutical companies to the enduring credibility of the banking sector, indicating the idea that the formidable physicality of architecture may not necessarily mirror the strength of these institutions, especially in an era where financial transactions predominantly take place on smartphones and the need for physical space by banks continues to dwindle.

The presence of modernist structures in the southern Sukhumvit quarter goes beyond public and commercial edifices to encompass religious places. Navigating through the extensive cluster of housing estates in Suan Laung, a neighborhood within the vicinity, the route led everyone to the Al-Kubror Mosque (1979), also known as the Grand Mosque of Kled Canal. Nestled on the bank of the Phra Khanong Canal, the mosque has been an integral part of the Al-Kubror Mosque community since the reign of King Rama I. Initially established in 1789, the mosque underwent reconstruction, and a new building was erected after more than two centuries had passed.

Diverging from the conventional architectural norms of many mosques, which often showcase dome-like structures adorned with intricate ornamental details, the Al-Kubror Mosque stands out with its simple yet visually captivating design. Glass windows with pointed arches accentuate the three-dimensional, curved concrete façade that envelops the area. These large openings encircling the prayer hall allow abundant natural light to permeate, creating a beautiful interplay of light within the mosque’s interior. The front minaret, with its subtly tapering form, harmonizes with the architectural language of the mosque. While the designer’s identity remains uncertain, the finesse demonstrated in the concrete construction, with a thickness not exceeding 10 cm, imparts an airy and graceful appearance to the entire structure. These structural details suggest that the individual behind the design must have possessed a commendable level of engineering expertise.

The final stop on the architecture tour is not too far away. Aliatisorm Mosque (1970), locally known as Mai Hua Pa Mosque, is situated along the Phra Khanong Canal. Designed by Paichit Pongpunluk who is also an architect of the Central Mosque of Thailand, the mosque boasts distinctive rectangular prism-shaped columns that spiral upward, gradually transforming into flat beams, creating an open and geometrically pointed arch structure. Inside the mosque, unique details on the circular stepped ceiling and ornamental designs on the geometrically shaped arches, adorned with brass motifs, capture attention. The dome at the center of the prayer hall features openings with inserted glass panels, allowing indirect light to illuminate the interior.

These two mosques not only preserve their beauty and adhere to religious traditions within the modern architectural context but also encourage contemplation on ‘cultural fluidity’ resulting from the advancement of public transportation systems. The connection between the two mosques, tied by people who once shared and commuted through the Phra Khanong Canal, reflects an ongoing cultural exchange that continues to this day. Architecture, in its own way, sustains this exchange, although at varying speeds and quantities, given the different capacities of long-tail boats and skytrains.

“I found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble” – Julius Caesar

The quoted text is a reference that Boonchai and Salyawate made during the conclusion of the journey. It poses questions to the participants, seeking their perceptions of the development and ongoing transformation of Bangkok. In a city with such rich history and a dynamic architectural landscape, creations of the past and present continue to evolve and contend for survival.

Although the SPACE SEEKING – South Sukhumvit Architectural Tour focused on a small area of Bangkok, such as South Sukhumvit, it serves as a case study to deepen one’s comprehension of the architecture of yesteryear. In the end, the image of the dream city one envisions resides in the values attributed to the architecture that has been created. Some may associate these values with business potential, others with historical significance, community ties, or even sheer beauty. These values, collectively shared by society members, can lead to the most straightforward answers to the earlier questions. But before getting there, a starting point may involve exploring and appreciating the values that have emerged and existed in this place over the passing course of time.