THE PROPELLER GROUP OF HO CHI MINH CITY ARE TAKING ON CHICAGO, AS THE FIRST COLLECTIVE AND ARTISTS WORKING IN ASIA TO BE SELECTED FOR THE MCA’S ‘ASCENDANT ARTIST’ SERIES.

art4d caught up with the Ho Chi Minh City-based collective to learn about how mechanisms such as advertising, ritual and metaphor come into play within their practice.

I understand that, working in HCMC, your decision to register the Propeller Group as an advertising company brought with it the increased ability to access channels you were interested in utilizing within your practice.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen – As soon as I graduated from Cal Arts I decided to move to Vietnam to work on some projects and started working on a film project with Phunam about the first generation of graffiti artists in Vietnam. We soon enough found out that at that time, it was very difficult to shoot in public without getting the proper permissions. We would get questioned by the police and they would threaten to confiscate our equipment, which back then was bigger that it is now, so we started talking and thought why not just get the proper permissions to become a film studio? We found out that it was actually very easy to set ourselves up as an advertising company and get even more access to the public advertising space. So that was when we started to register the project as a company, as an advertising company.

Your recent work, ‘Television Commercial for Communism’ is one example of how you explore the character of advertising, mass media and dissemination strategies in your work. The piece calls upon what you describe as Capitalism’s most influential byproduct [advertising] to rebrand its former political opponent – Communism.

TAN: The initial idea was to represent the last five remaining communist countries in the world and have them hire the top advertising agencies to rebrand Communism. Because of our work in the industry here, we knew a few advertising companies and we reached out to TBWA, they had just set up shop in Vietnam maybe no more than 5 years ago and they are renowned for working on the Apple adverts and for big brands like Gatorade and Nissan. So we reached out to them and they agreed, surprisingly enough. For us, the process was going to be the most important thing, them trying to figure out and reconfigure this ideology and process it through the mechanism of advertising.

[read more = “Read more” less = “Read less”]

Matt Lucero: I had never been to a Communist country before coming to Vietnam, so I had these ideas of what that was like, and pretty much those ideas are filtered through the media, film and history. I thought that it was this socialist ideal, this utopian society where Capitalism doesn’t exist in the way that it exists in the United States. It is a different sort of system, right? Coming here and being greeted by the propaganda imagery and the stuff that I was expecting and then going to the center of the city and seeing Chanel and Louis Vuitton and all these global brands; I was kind of surprised but I guess it wasn’t so surprising either. One of the interesting things is this coexisting that happens between the global marketplace, global capitalism and the systematic framework of politics here, which is Communist, and how they operate together. What was interesting was hearing this advertising company think about what they are doing here – how they are operating, what it means to operate here and what the ideology means in both senses, for advertising and for Communism. A large part of the dialog they were having was in trying to figure out what Communism meant today. They ended up pointing to the Wikipedia definition, which is sort of the most general definition, as the starting point and then the campaign grew from there. It was a pretty good demographic of people in the agency that were represented. There was a Chinese-American, a Vietnamese-America, a Vietnamese national, an Indonesian, and an Indian so it was a fairly wide and young generation coming to this and they all had different perspectives. One person’s perspective is different because of how they experienced things in their country, and then they come here and it shifts a little more. We recorded their brainstorming sessions, known in the advertising world as tissue sessions. Ultimately, it was this world that a young girl is traversing in and she is having these experiences with different groups of people. In these interactions, a smile is exchanged between them and she gathers all these smiles, in a way they become a sort of currency. At the end of the day, there is a large gathering and she distributes this collection of smiles. Everybody comes together and forms a symbol for the new flag of Communism.

TAN: The process that the creative team at the advertising agency engages in, that is what we were interested in, so our idea was to document every kind of tissue session that they had and we ended up with a five channel video installation that runs about 5, 6 hours. The roundtable situation was something that was an important element because most brainstorming happens around a roundtable in the advertising field and we documented with five cameras from the outside of the table shooting in. When we show it, we show it kind of inversed where people can enter inside of the five projections so that you are in a way inverting that process, that brainstorming process and that roundtable process and it also looks like the star which we were interested in as a play on the visual.

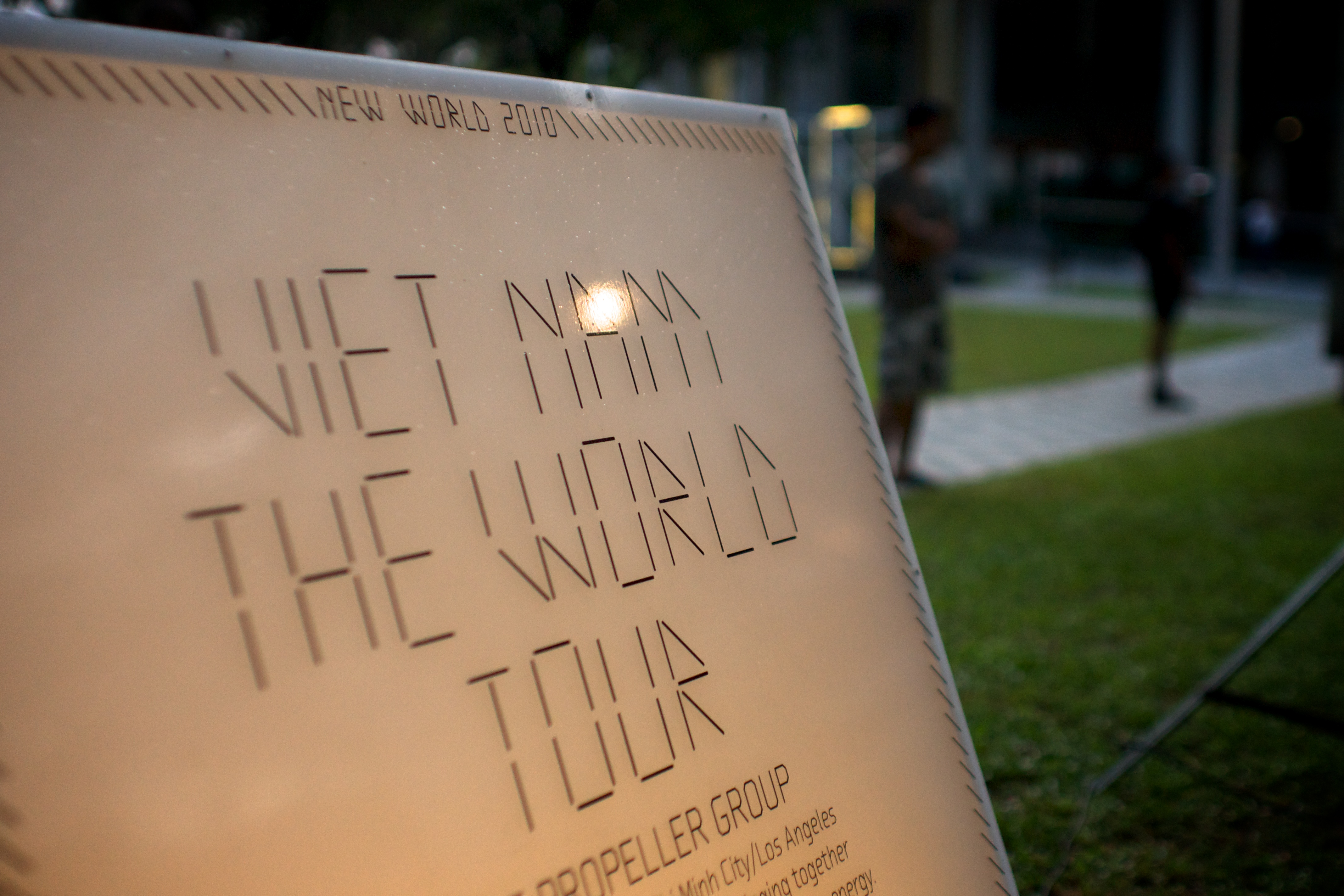

Your project, Viet Nam the World Tour also explores artistic practice as envisioned through marketing tactics and ‘nation-branding’ or rather an ‘anti-nation-branding campaign’?

ML: Yeah, at the time that project started we were really interested in nation branding and what advertising agencies were currently doing to rebrand nations. I think around that time Australia had hired Saatchi and Saatchi to rebrand Australia. So they redesigned the boomerang and they had this whole series of visual campaigns about the diverse population of Australia. When one thinks about Vietnam, especially for me growing up in the US, a lot of media, films and news footage comes to mind, which is largely based around the conflict here, the American war here in Vietnam. When you do a Google search, a lot of that history still comes up and is still present. So it is moving towards this idea of the online archive and Google as an image archive. When you search it and what comes up, what you see and what you find, we were interacting with that archive with this project and it was a way for us to interject and try to change the archive in a way or alter it, maybe even for a moment, so that when you search for Vietnam something else would come up and hopefully, maybe, it was Viet Nam the World Tour. Some kid doing graffiti or breakdancing or expressing themselves in a completely unexpected way, and I say unexpected from my perspective of growing up in the US and doing those searches and finding that sort of generic referential media from the past. Looking forward into what the future representation of a nation could be, through this archive.

TAN: We were really interested in Vietnam as a nation brand not only because we were based out of Vietnam, but because historically Vietnam has become the most mediatized nation brand in history. So we thought that would be the challenge, to kind of balance out that national identity that was created through all the media that was generated by the press during the war with our new media. We all grew up doing graffiti and dealing with public space and advertising, how advertising colonizes public space. When we started to think about this project, we were really interested in thinking about the Internet as a new kind of public space.

ML: For Viet Nam the World Tour we had a series of brand ambassadors that we were working with. Some of which are really popular online and they have millions of followers, so it was interesting thinking of it from a branding, advertising perspective. If you think of El Mac, who is a graffiti artist in LA who has millions of followers and does murals all around the world, we have him go to different places and he does his thing and then he writes ‘Viet Nam the World Tour’ on his mural. So, when his followers see that it points back to our archive and there is this questioning that happens, as a viewer and as a fan, that is a little skewed.

Phunam: A little of an interruption.

ML: It peaks a little bit of curiosity. What does that mean? Why is he writing that? Is that a crew? Is he Vietnamese? There is an important questioning that happens.

I think that in a lot of your works you kind of hint or set it up for the viewer to follow their own trajectory without too commandingly dictating where they should arrive.

TAN: Ultimately, we don’t want to be didactic in our work, and we don’t want to tell you what to think. We want to create a project that opens up space for thought, for questioning and for people to be critical in their own space. That is something that we think about all the time and when we are discussing projects. We always challenge each other to develop projects that do that. It helps to have three people thinking about whether or not the project is too one-dimensional or not.

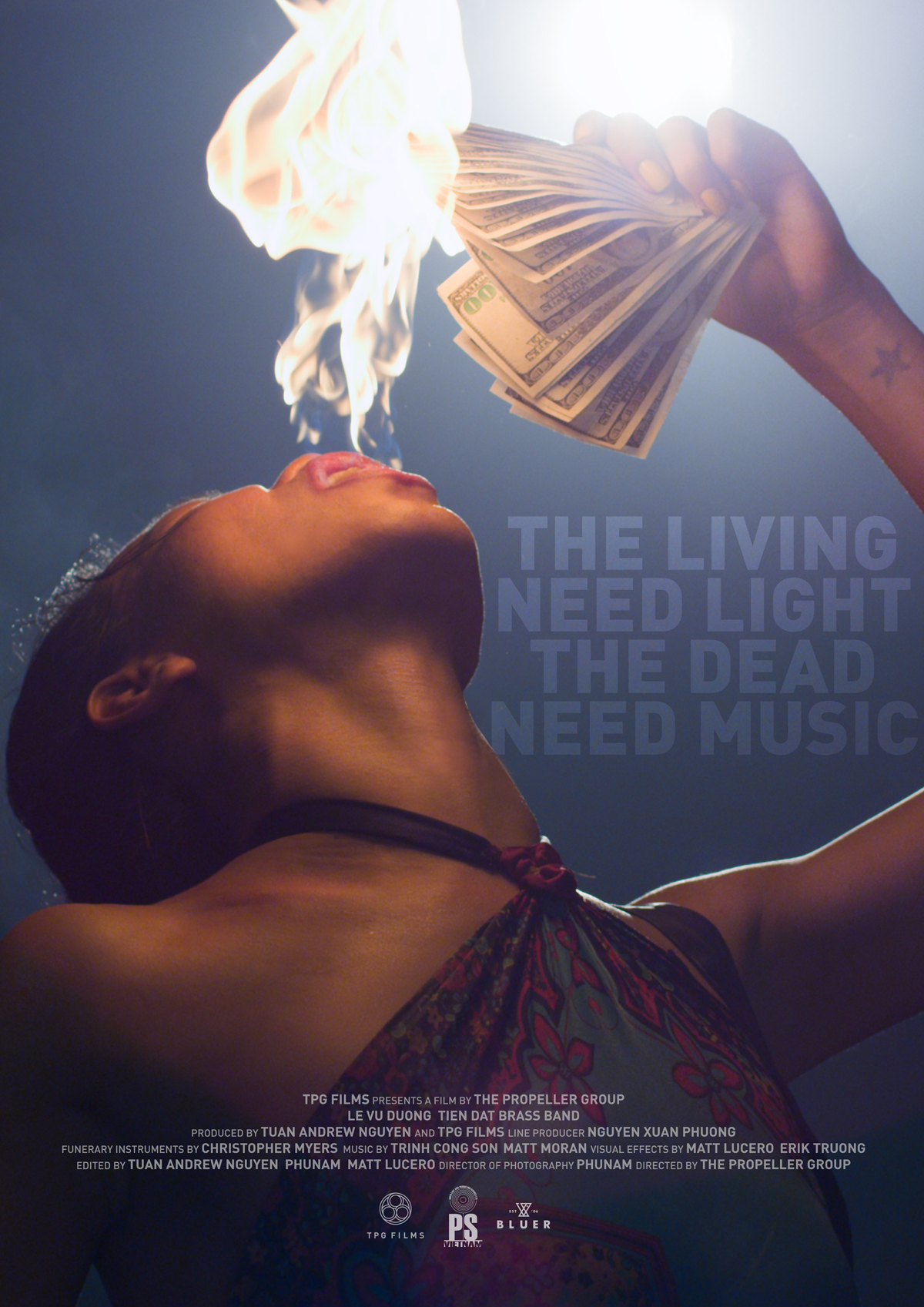

Your recent video work, The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music is a good example of such; the film is a part documentary/ part re-enactment of traditional funeral processions in Vietnam?

TAN: It has a lot to do with going beyond and that is how I kind of read it. If you look at some of the rituals and the performances that happen during these funerary processions, it is almost as if they are going face-to-face with death – people swallowing swords and dealing with poisonous snakes. It is less like upholding a certain memory but more like the living having to deal with the idea of death and the dead having already dealt with that process, so it is more for the living than figuring out what death means, and I think for us all there was something very poetic in that.

The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music, Image © The Propeller Group

ML: The first time that you see a funerary celebration here it is pretty amazing. Traffic stops and people watch, it is part spectacle, part honor, part of what can you do to provide a memory? These performances get pretty wild and the best memory that you can have are these crazy spectacles because you are never going to forget that and you are going to remember that person who the funeral is for. It is an honor to have that kind of spectacle happen.

TAN: We collaborated with Christopher Meyers, who is a visual artist and a writer based out of Brooklyn, New York. He was really interested in creating the instruments that you see in the film which were beyond the reality of the instruments that we typically see. We wanted to explore the different sort of metaphors that these rituals were hinting at and a lot of the funerary traditions move very easily between the real world and the other world in their performances, rituals, dress, instruments and props, so it was essential for us to merge those two things together, the documentation of these funerary traditions in Vietnam and the other world – like these very fantastical and liminal kinds of objects that could exist, somewhere else and everywhere else.

The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music, Image © The Propeller Group

You have collaborated with a lot of others as well, and are many times the catalyst of those collaborations, I imagine that this ensures new and multiple dimensions finding their way into your work.

TAN: Yes, and we collaborate with people that aren’t necessarily operating in the contemporary art world, which is helpful for us because we are really interested in that public space and how media operates in the public sector. So a lot of the people we collaborate with are people that operate in different spaces in that idea of the public. I mean Ho Chi Minh City is an interesting space to be making work in, we don’t exhibit a lot here, just because of the content of our work; we know that we wouldn’t get permission to show. I think that in the first few years that we were here making work, it was such a complicated political space, and complicated media space, that it offered us a lot of things to think about and those things seeped into our work.

The Propeller Group, Photo by Worarat Patumnakul

Could you introduce your project, ‘The AK47 vs the M16’?

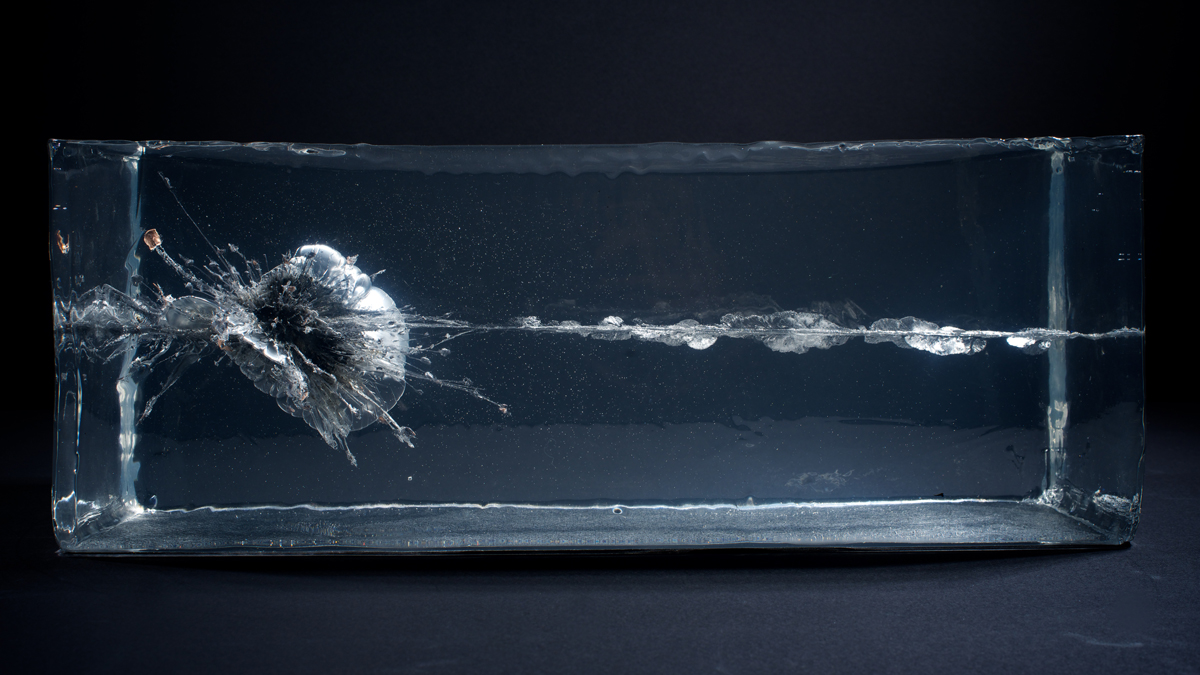

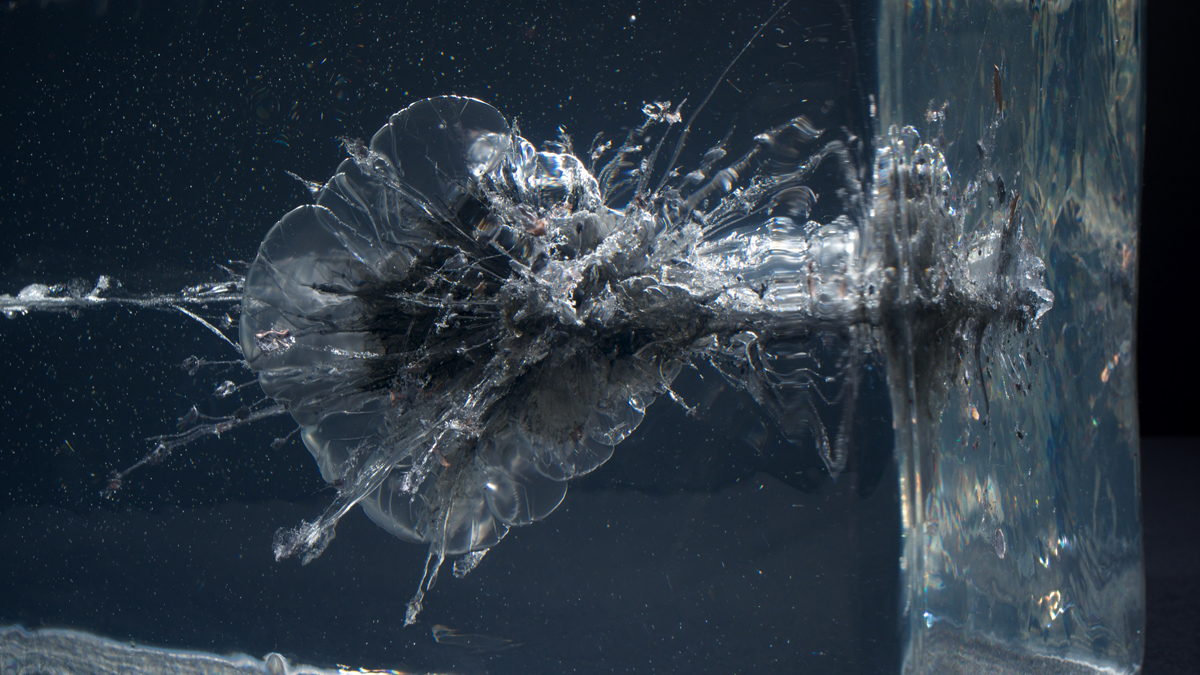

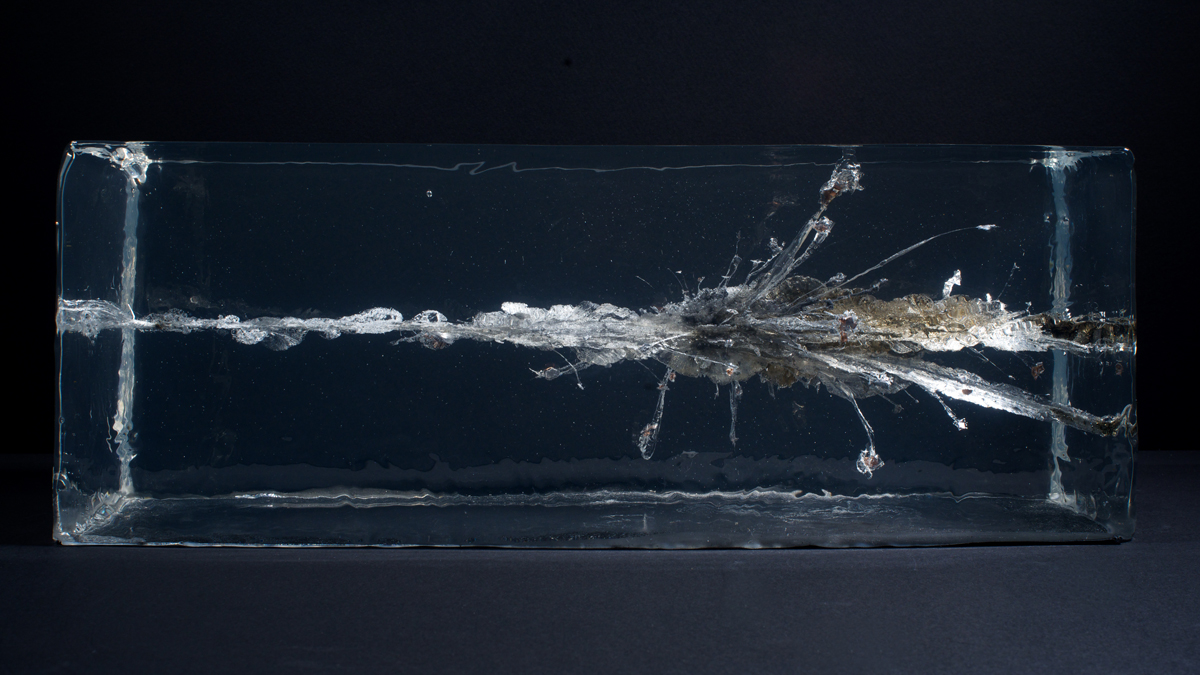

TAN: It is a work called the AK-47 vs the M16 and it is a project based on a bullet that was found on the American Civil War battlefield that collided in midair and fused. We thought that the object was really interesting and could talk about a lot of different things. Statistically, the chances of two bullets hitting in midair are one in a billion, even considering the amount of lead flying back in forth. We liked the potentiality there and wanted to play with that impossibility. We also wanted to apply to that a kind of a Cold War era concept by using two very iconic weapons that came out of the Cold War, which were the AK47 and the M16. We worked with a ballistic company to fire an AK-47 and an M16 together, to make the two bullets fuse. That was the intent, but the bullets didn’t fuse, they shattered, so we ended up shooting them into ballistics gel blocks to capture that moment of impact as it shattered.

The AKG vs the M16, Image © The Propeller Group

ML: In addition to the gel blocks that captured the collision we are also working on a film where we are looking at all of the instances where the AK-47 and the M16 have been used in media, popular films, documentaries, even YouTube videos and there is a lot – it is overwhelming. I mean just in films alone, there are thousands and thousands of instances where these guns have been used and we are digging through these archives and pulling these moments together. It is culminating into a really wild shoot out of a film that is almost like an endless battle happening. So we are re-editing this footage into one long, like 6 hour, battle scene where you will see the AK-47 and the M16 just shooting back and forth at each other.

The AKG vs the M16, Image © The Propeller Group

TAN: The AK-47 is the most widely distributed weapon in the world, over 100 million have been produced and we are thinking about how it is represented and how people interpret the violence that it’s been connected to. It is an icon that is contradicted in and of itself, as a symbol for revolution, of freedom fighters and for kicking out the colonialists, but at the same time it is a symbol for terrorism as well. So between the freedom fighter and the terrorist, it occupies a very interesting social and psychological space. The M16, I would say, represents everything American.

ML: There are these tropes that are inherent in the weapons. You see these films, the context that these weapons are used in, what character gets to use what and how they’re branded. They sort of embody that ideology and there is a lot of things to unpack.

You are going on your tenth year of collaborative practice. Where do you see your focus being driven next? Are there certain concepts, or media that you feel compelled to explore or push further?

TAN: We have been talking about ourselves as a brand. We started because we wanted to deal with issues in branding and what that means today, politically and socially. But locally, and maybe possibly in the art world, we have become a brand ourselves, so we are interested in maybe opening that up, distributing the brand to other artists or collectives to use somehow, and opening the process of collaboration up even more.

ML: I try to see the future as open, and thinking of a model that is open is interesting – a more flexible, and open collaborative model.

‘The Propeller Group’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago runs through Nov 14, 2016

[/read]

mcachicago.org

thepropellergroup.com