TO REALLY SEE THE BIG PICTURE, WE MAY HAVE TO RETRACE THE ROUTE OF THE FIRST WAVE OF IRANIAN CINEMA THAT FOUND ITS WAY INTO THE WORLD’S CINEMATIC MAP BACK IN THE 90S THROUGH ITS MOST SIGNIFICANT CHARACTERS — CHILDREN.

On July 4th, 2016, Iran and the world lost one of its greatest and legendary filmmakers, Abbas Kiarostami who at the age of 76, passed away from cancer. He was one of the most prominent film directors during the late 1980s and the early 1990s. His contributions put the Iranian film industry on the international map while his powerful cinematic language continues to influence generations of Iranian filmmakers. And while the country’s film industry has found some new sources of content and presentational approaches (such as horror, sci-fi and thrillers) one cannot deny that the connects Iran to the world of the cinema. To really see the big picture, we may have to retrace the route of the first wave of Iranian cinema that found its way into the world’s cinematic map back in the 90s through its most significant characters — children.

Most of the internationally famous Iranian films produced during the 80s and 90s were full of stories about children. From ‘Where is the Friend’s Home?’ (1987) to the featuring of children during the Iraq-Iran War in ‘Bashu, The Little Stranger’ (1989), or a friendship that takes place in a dire rural area of Iran amidst language differences in ‘Dance of Dust’ (1992), a girl looking to buy a goldfish in ‘The White Balloon’ (1995), a teenager with no knowledge of history in ‘A Moment of Innocence’ (1996) and two underprivileged siblings who couldn’t afford shoes to go to school in ‘Children of Heaven’ (1997) or a girl imprisoned in her own home for her father’s fear for the outside world in ‘The Apple’ (1998), there are countless noteworthy examples. Compared to other genres of movies from Iran, these particular types of films are only a part of the industry that produces films from many diverse categories; but, from the eyes of outsiders, is also the genre that represents the first era of Iranian cinema. But why is that? What we can do to find out is go back and look at the evolution of the overall history of the Iranian cinema, both pre and post-Islamic Revolution.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran became an Islamic republic with a legal code based on Islamic or Sharia law. One of the things the postrevolution government did was to demolish the secular norms of the old system under the reign of the Pahlavi Dynasty that had ruled the country since 1921. The Pahlavi Dynasty favored western modernity and glorified pre-Islam Persian culture, viewing the religion as an obsolete tradition. In the eyes of the religious leader, film was one of the symbols of the decay and deterioration of the West. Before and after the revolution, the burning and destruction of over 180 cinemas nationwide was a symbol of opposition against the Pahlavi Regime with only 256 cinematic venues remaining after the end of the revolution.

But even with the new government in power, the medium was not entirely banned from the country for while Khomeini, the revolution’s leader viewed film as a source of deterioration, he and other religious leaders also believed that the medium could benefit the nation if used wisely. The government, therefore, chose to use film as a tool in their attempt to bring cinema under the domination of the state ideology and subject it to a process of Islamization despite the fact that there was never such a thing as an Islamic cinema.

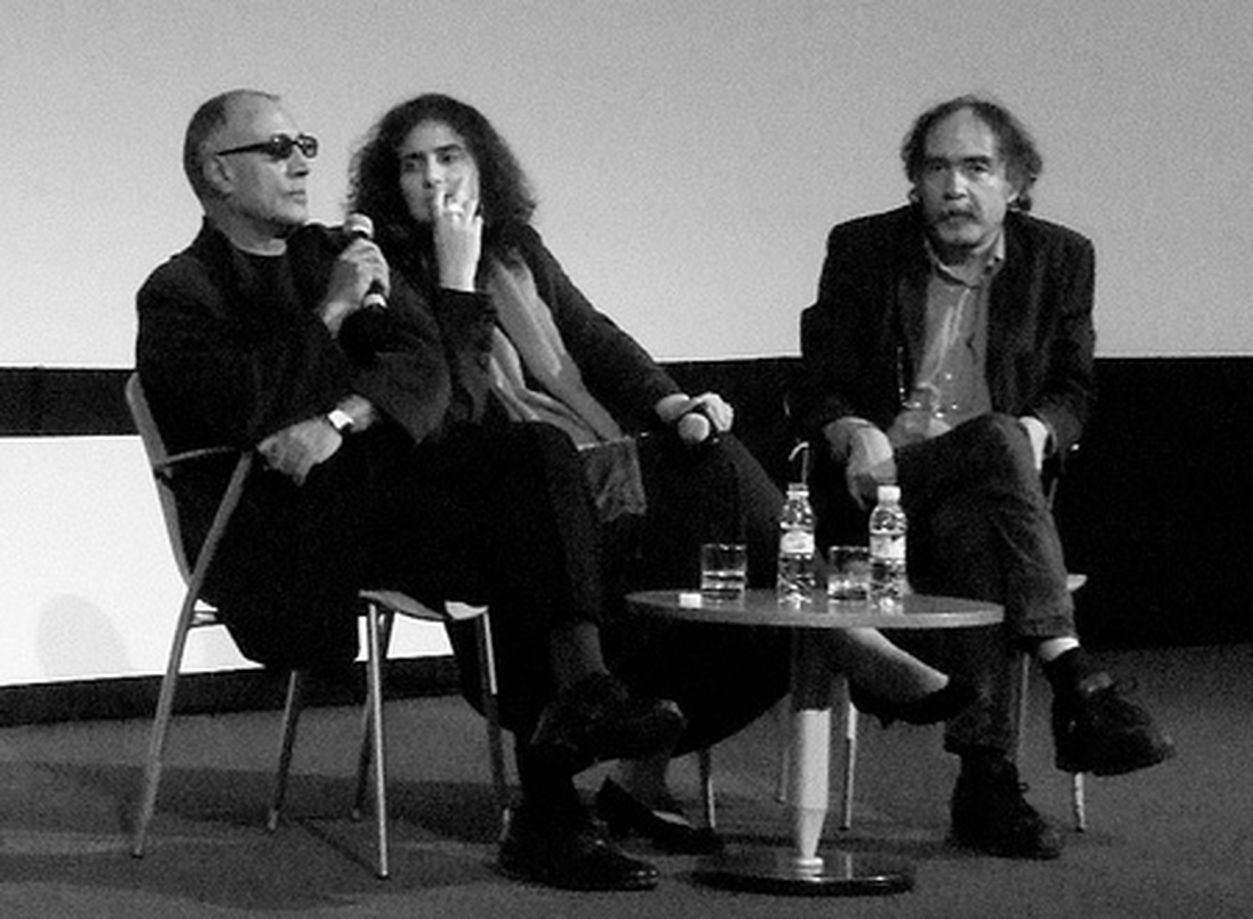

Abbas Kiarostami, Paulo Branco at Estoril Film Festival 2010 © Miguel Teixeira

During the 1980s, the government controlled the content of films, from the screenwriting stage all the way to the screening. Filmmakers therefore had a hard time telling the stories of their country with several rules and regulations limiting their freedom. The male characters were prohibited from wearing short-sleeved shirts unless they were bad guys while female characters could never wear make up. Close-ups on female characters’ faces were not allowed and they were required to cover their entire body with a burka even in scenes where the characters were at home with their family members. Women were not supposed to walk or move their bodies too much for they could be viewed as a source of arousal. As a result, the women in Iranian films often stood or sat still while the male characters led the stories. From 1980 to 1988, during the period when Iran was in a war with Iraq, the subject matter of the films produced revolved around war, the glorification of religious teachings (not to value money) or the opposition directed toward the old system and Pahlavi Regime. The films from this particular period were primarily propaganda films promoting both religious and nationalistic beliefs of the new ruling regime with repetitive plots, ridiculously flat characters and restlessly inserted teachings. Simply speaking, the content of Iranian films during the 1980s was highly propagandized and politicized.

The end of the war was followed by less strict control and censorship measures due to the government’s satisfaction in the already deep-rooted Islamic beliefs in the society, granting filmmakers more creative freedom in 1989. The post-war period was also the time when Iran was starting to adjust itself to the western world and cinema was seen as an important tool for doing so. As a representation of innocence, children in Iranian films were able to do what the adult characters couldn’t, whether it be singing, expressing their feelings or participating in behaviors and actions such as simply strolling down the street because children didn’t have jobs or responsibilities. But, it was through their journeys that international audiences were able to explore the urban and rural Iran. The innocent spirit created a new perception for the country that has always been perceived as a land of radical Muslims. The less dramatic plots allowed for filmmakers to be less worried about storytelling and more focused on the contemporary social climate while the use of amateur child actors further contributed to the realistic quality of the films. The cinematic creations coming out during this particular period contain several attributes of poetic realism as children characters symbolized the new beginnings of the country that was free from all extreme political movements. They are not aware of the effects of war and the revolution, but somewhat the victims of these incidents’ tragic fallouts. They were not a part of any of it and did not possess any political beliefs that could be targeted by the state’s censorship mechanisms (regardless of the filmmakers’ own political beliefs).

There is one significant difference between the Iran cinema’s realism and neorealism in its films from that of other countries that highlights the reflection of social issues. Iranian filmmakers utilize highly diversified cinematic languages, from long-takes playing with the space both inside and outside of the frame to editing that simplifies the rationality of the plot and causes the films to be more poetic in their search for reality as opposed to the straightforward approach to storytelling that most documentaries favor. Kiarostami’s prominent recognition in the international arena is derived from such a poetic and universal language. It comes as no surprise that he was able to continue producing works in his cinematic style in Europe and Japan during the latter years of his life. But that isn’t always the footsteps other filmmakers follow in. Children might be the key to the new cinematic landscape of Iran, but, naturally, they grow up. Some filmmakers choose to discuss other social and political issues such as women’s rights, minorities, social classes, freedom of expression and so on, while the attempt to hide their messages behind the children is no longer.

Abbas Kiarostami-Murcia ©Pedro J Pacheco

TEXT: RATCHAPOOM BOONBUNCHACHOKE

The Apple (1998) a film by Samira Makhmalbaf

The Apple (1998) a film by Samira Makhmalbaf