THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK, AN ART EXHIBITION BY PRATCHAYA PHINTHONG AT BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY, RAISES A QUESTION OF ‘HOW MUCH TIME ONE SHOULD SPEND IN AN EXHIBITION SPACE’ AFTER WALKING INSIDE THE EXHIBITION ROOM THAT LOOKS ALMOST EMPTY

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For English, please scroll down)

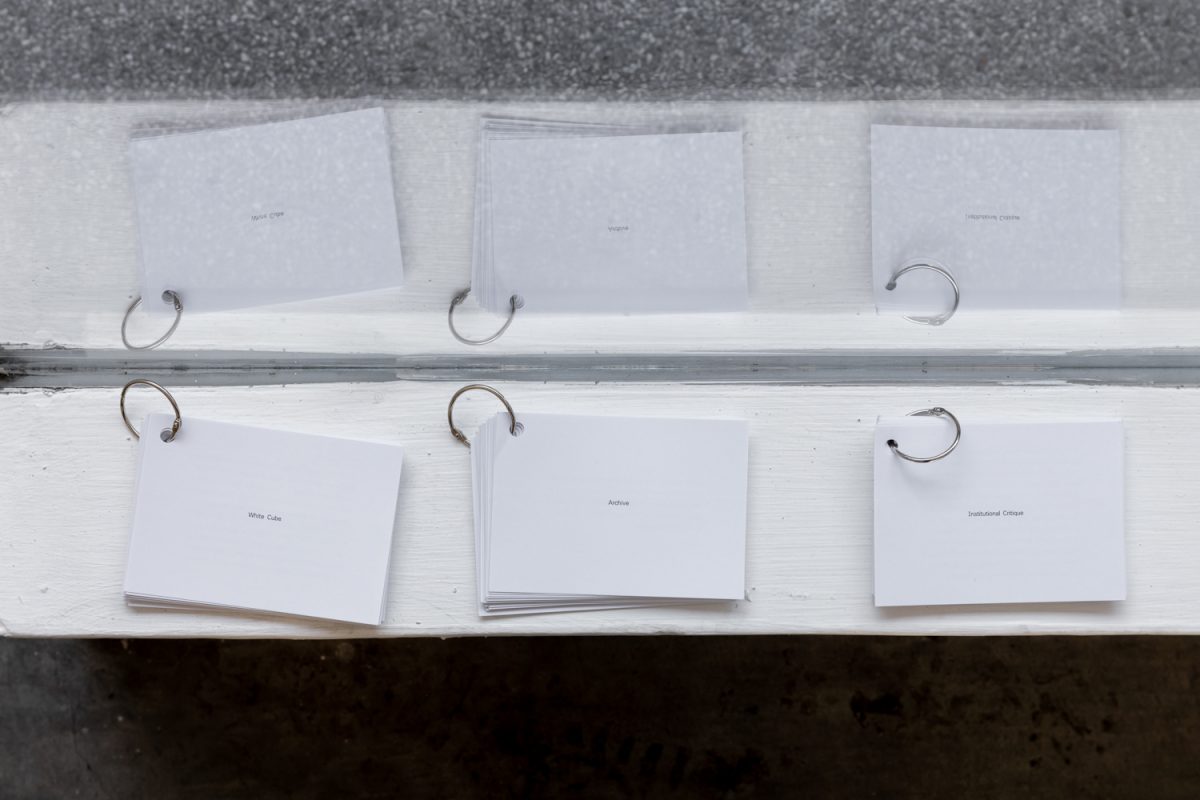

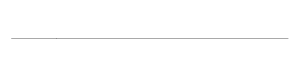

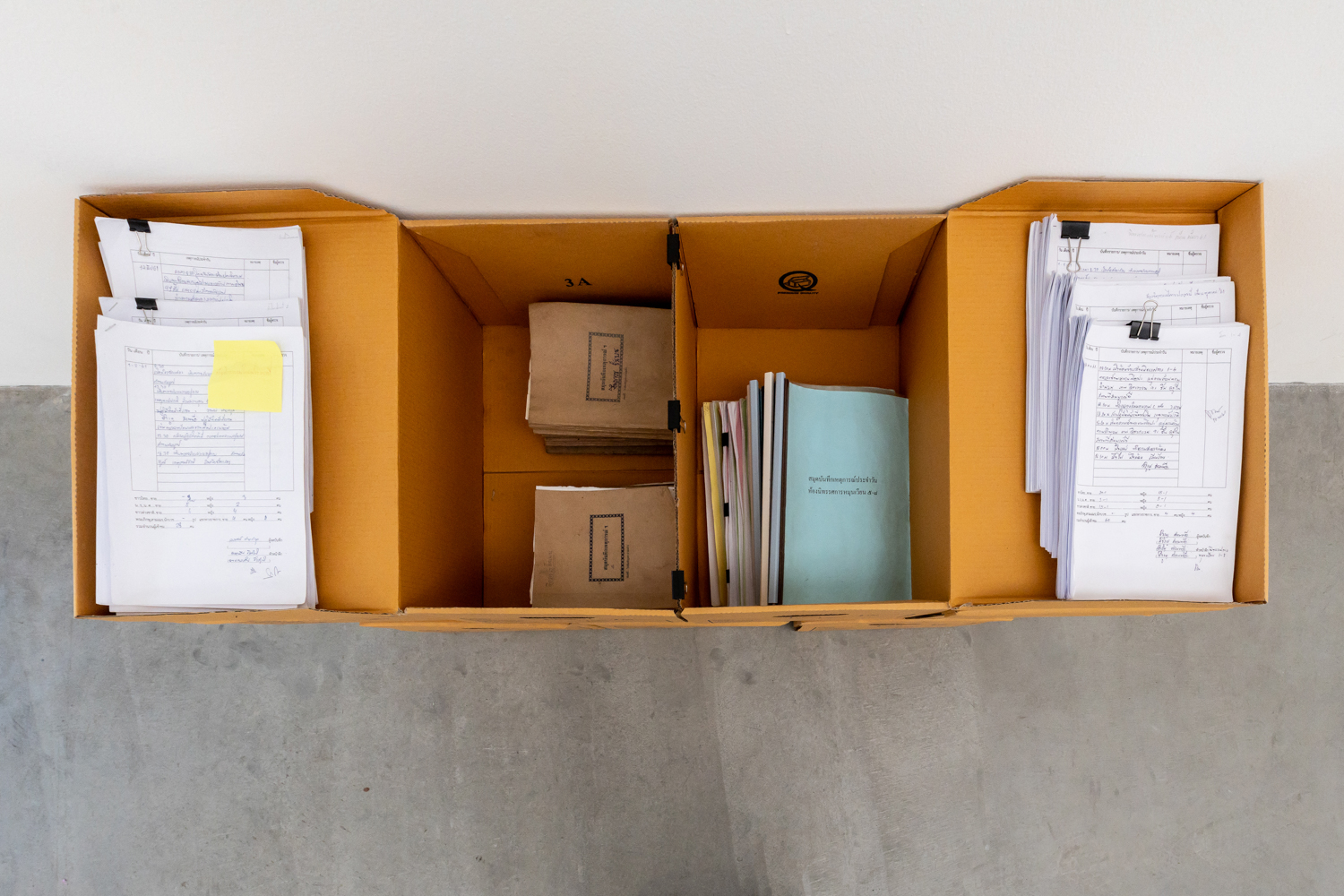

ห้องนิทรรศการเรียบร้อยกว่าที่คิด ผนังแกลเลอรี่ถูกปล่อยให้ว่าง (?) เราเดินออกมาจากห้องนิทรรศการหลักเพื่อมองเข้าไปในห้องนิทรรศการย่อยเผื่อว่าจะมีอะไรติดอยู่บนฝาผนังหรือไม่ –กลายเป็นออฟฟิศของแกลเลอรี่ไปแล้ว กลับมาสังเกตห้องนิทรรศการหลักอีกครั้ง บนพื้นห้องมีไม้กั้นล้อรถวางอยู่เป็นระเบียบราวกับพื้นที่จอดรถของ 123 Parking กินเข้ามาในพื้นที่เแกลเลอรี่ ความผิดปกติอีกอย่างคือประตูปลายห้องนิทรรศการถูกเปิดออกเป็นครั้งแรก หันหลังกลับมาเราเจอเข้ากับกล่องลังบรรจุสมุดบันทึกเหตุการณ์ประจำวันของพิพิธภัณฑ์สถานแห่งชาติ หอศิลป และบัตรคำศัพท์ที่วางอยู่ต่ำกว่าระดับสายตาใกล้กับประตูทางเข้า บัตรคำที่ว่านี้น่าจะเป็น text ชิ้นเดียวในห้องนิทรรศการที่อ่านได้ ประกอบไปด้วยคำว่า Archive, Deconstruction, Found object, Institutional Critique, Performativity, Readymade และ White Cube แต่มันก็ไม่ใช่ artist statement แบบที่นิทรรศการมีกันทั่วไปอยู่ดี

ศิลปิน (ปรัชญา พิณทอง) และ ธนาวิ โชติประดิษฐ คิวเรเตอร์ของนิทรรศการ จงใจตัดคำอธิบายออกไปจากห้อง ด้วยการผลักไปไว้ในวันสุดท้ายของนิทรรศการ (27 มกราคม) ที่จะเป็นวันเปิดตัวสูจิบัตรนิทรรศการและกิจกรรม artist talk มี text อีกชุดที่เกิดขึ้นนอกห้องนิทรรศการนั่นคือ “ลาก-เส้น-ต่อ-จุด” กิจกรรมที่นักศึกษาคณะโบราณคดีและนักเขียนศิลปินรุ่นใหม่จำนวน 5 คน จะเดินทางย้อนรอยประวัติศาสตร์ของหอศิลป์ในไทย เริ่มจาก พิพิธภัณฑ์สถานแห่งชาติ หอศิลป (หอศิลป์ เจ้าฟ้า) – หอศิลป พีระศรี จนถึง BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY ก่อนจะร่วมกันเขียนบทความขึ้นมาเพื่อประกอบเข้ากับบทความของคิวเรเตอร์ที่จะตีพิมพ์ในสูจิบัตร นอกจากนี้ยังมีกิจกรรมชวนอ่านจัดควบคู่กันไปถึง 2 ครั้ง อย่าง “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Jacques Derrida, 1995/1996)” โดย ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.เกษม เพ็ญภินันท์ สำหรับผู้สนใจทั่วไป หรือ “An Archival Impulse (Hal Foster, 2004)” โดย ดร.สายัณห์ แดงกลม ที่ผู้เข้าร่วมจะต้องอ่านบทความมาจากบ้าน เขียนเหตุผลว่าทำไมถึงอยากเข้าร่วมเพื่อผ่านการคัดเลือกเข้าร่วมกิจกรรม กิจกรรมทั้งหมดนี้เกิดขึ้นเพื่อกระตุ้นให้เกิด “บทสนทนา” ขึ้นในหมู่ผู้ชมเองก่อนจะฟังมุมมองของผู้สร้าง การกำหนดวิธีการชมงานแบบไม่ให้อ่าน text ยังแนะให้เห็นระนาบอื่นๆ ของการ “อ่าน” ซึ่งไม่ได้ไปลงอีหรอบของการอ่านภาพตามวลี “เสพศิลปะ” ที่ถูกใช้กับการดื่มด่ำลงลึกไปกับเส้นสีฝีแปรง อารมณ์ สายตาของ figure ในภาพ สิ่งนี้ที่ทำให้นิทรรศการนี้น่าสนใจ เพราะสิ่งที่พึงอ่านเป็นอย่างแรกนั้นคือเจตนาของศิลปินที่จงใจสร้างความว่างเปล่าขึ้นมาต่างหาก

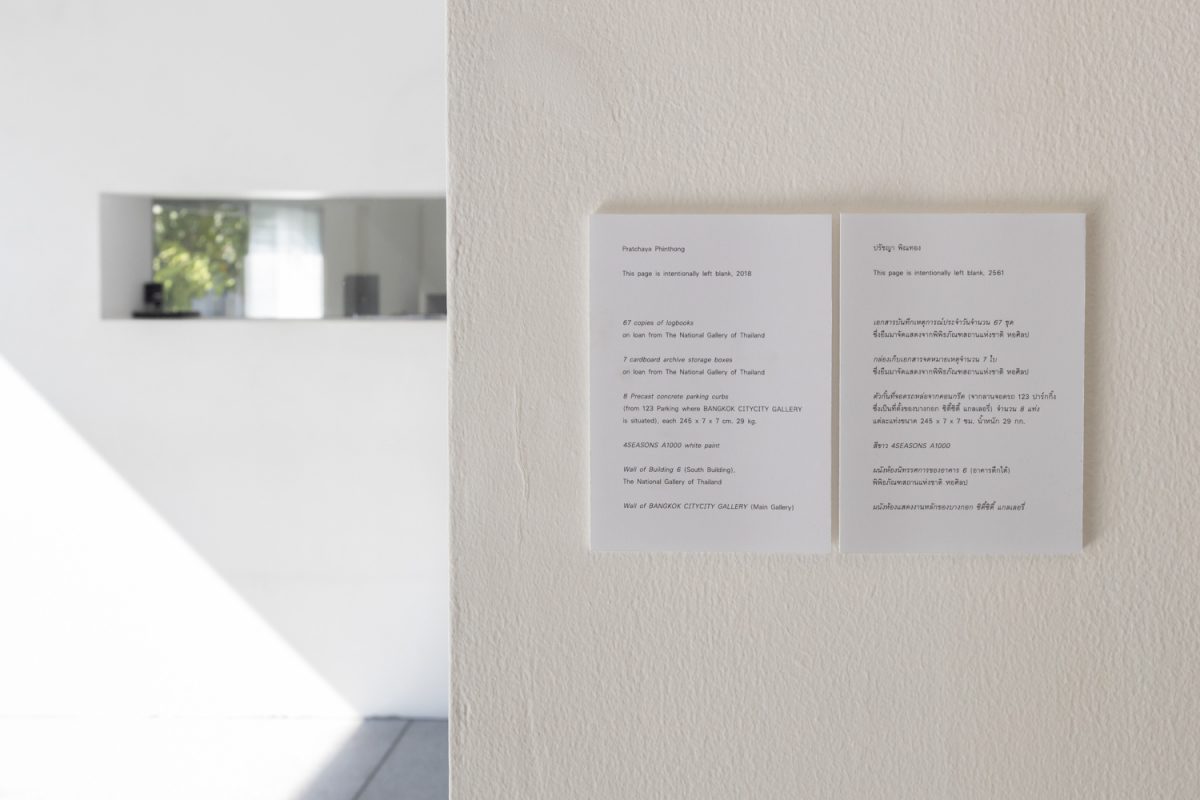

“Poster นิทรรศการมันเป็นเหมือน soft invitation ที่กระตุ้นให้คนมองความว่างเปล่า ว่าจริงๆ แล้วมันมีอะไรบนนั้นบ้าง รอยพับ สีขาว เส้นตรง เงาของสีและแสง สิ่งที่น่าสนใจคือเราจะเห็นการมีอยู่ของพื้นที่ว่างเปล่าได้อย่างไร?” การมองเห็นพื้นที่ว่างเปล่าเหมือนจะเป็นไอเดียที่สำคัญของนิทรรศการนี้ แต่พื้นที่ว่างเปล่าที่ว่านี้จะแสดงตัวออกมาภายใต้เงื่อนไขบางอย่างเท่านั้น ปรัชญาเล่าถึงวิธีการสร้างพื้นที่ว่างบนหน้ากระดาษด้วยการใช้ประโยค “หน้านี้จงใจให้ว่าง” ในอุตสาหกรรมการพิมพ์ว่า แปลกดีที่พื้นที่ว่างเปล่าจะถูกอ่านว่าว่างเปล่ามันจำเป็นต้องพึ่งพาการปรากฏขึ้นของบางสิ่งที่ช่วยระบุว่ามันว่างเปล่าพร้อมๆ กับทำลายความว่างเปล่าไปพร้อมๆ กัน กับนิทรรศการนี้ การสังเกตเห็นป้ายชื่อผลงานคือเงื่อนไขที่ว่า ส่วนรายละเอียดที่ต่างไปจากการใช้ประโยค (หน้านี้จงใจให้ว่าง) มากำกับคือ มันไม่ได้ปะทะสายตาคนตั้งแต่แรก ไซส์มาตรฐานของป้ายแคปชั่นปล่อยให้ผู้ชมตะลึงกับความว่างเปล่าของผนังอยู่พักหนึ่งก่อนจะค่อยๆ เผยตัวออกมาจากผนัง และชื่อผลงาน 4SEASONS A1000 ก็มายืนยันว่าจริงๆ แล้วในความว่างเปล่าที่เราเห็นนั้นไม่ได้ว่างเปล่าแต่คือผนังสีเบอร์เดียวกันกับที่ใช้ทาที่พิพิธภัณฑ์สถานแห่งชาติ หอศิลป

โพสต์แนะนำศิลปินของ BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY เรียกปรัชญาว่าเป็นนักเล่นแร่แปรธาตุตัวยงที่มีกระบวนการทางศิลปะที่แทบจะมองไม่เห็นได้ด้วยตา แต่อีกบทบาทที่เราคิดว่าปรัชญาทำได้อย่างแนบเนียนครั้งนี้คือการสร้างสถานการณ์ ที่ทำให้หลายๆ สิ่งที่ไม่ได้เกี่ยวข้องกันกลับมารวมอยู่ในที่เดียวได้อย่าง (ดู) สมเหตุสมผล

“มันมีหลายดีกรีของการทาสี จะเล่าให้มันธรรมดาก็ได้ จะเล่าให้มัน delicate เลยก็ได้ สีขาวเป็นสารัตถะของสิ่งเหล่านี้ทั้งหมด เราใช้มันเพื่อผลักระยะให้ไกลขึ้น เพื่อจะเน้นย้ำให้วัตถุหรือไอเดียกระโดดออกมาจากพื้นหลังนั้น White Cube มันเป็นแค่การขังแสงเพื่อให้เกิดพื้นที่ให้เกิดเงื่อนไขอะไรบางอย่าง” สีขาวของปรัชญากลายมาเป็นไฮเปอร์ลิงก์เชื่อมไปถึงศัพท์ทางประวัติศาสตร์ศิลปะคำว่า White Cube บนบัตรคำศัพท์ของคิวเรเตอร์ ที่สืบย้อนกลับไปไกลได้ถึงการสถาปนาอำนาจในการกำหนดขอบเขตพื้นที่ศิลปะที่เกิดขึ้นตั้งแต่ศตวรรษที่ 20 ในโลกตะวันตก ไล่มาถึงพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ หอศิลป และห้องนิทรรศการของ BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY นอกจากนั้น การจัดแสดงสีขาวในฐานะงานศิลปะโดยตั้งใจไม่ให้ถูกมองเห็นอยู่พักหนึ่งยังทำให้เราเห็นนิสัยการทำงานศิลปะของปรัชญา นั่นคือการเล่นกับความคาดหวังของผู้ชมนั่นคือการปรากฏตัวของวัตถุ

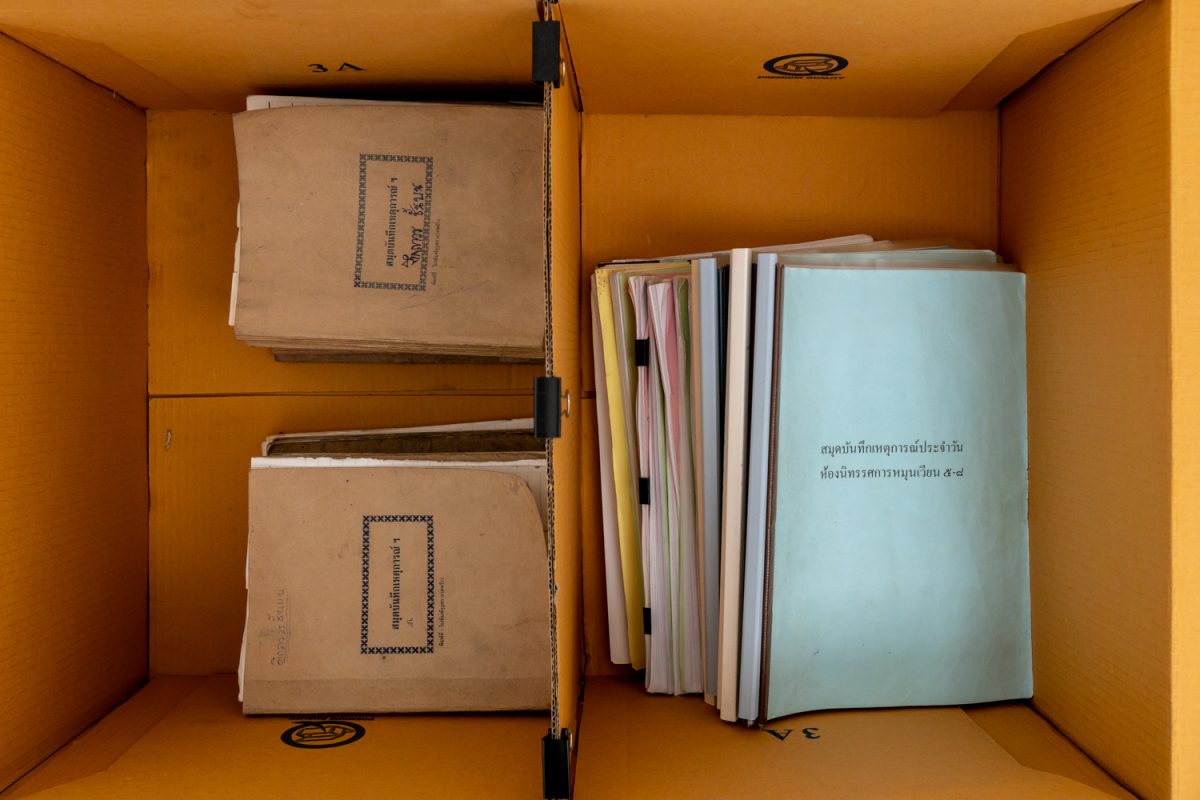

ตรงนี้เองที่คำถามของคิวเรเตอร์ที่ลอยอยู่ในอากาศว่า “อะไรทำให้ศิลปะเป็นศิลปะ” กลับเข้ามา ตอนที่ศิลปินและคิวเรเตอร์ดำเนินการขอยืมสมุดบันทึกมาจัดแสดง คงเป็นครั้งแรกที่สมุดบันทึกเหล่านี้ถูกนับว่าเป็น “วัตถุจัดแสดง” ตามที่ระบุในใบยืม – คืนวัตถุจัดแสดงของพิพิธภัณฑ์ เช่นกันกับปฏิกิริยาของเจ้าหน้าที่ดูงุนงง สับสน ปนระแวงว่าทั้งศิลปินและคิวเรเตอร์จะเอาของเหล่านี้ไปทำอะไรกันแน่ ที่ยืนยันถึงความสำคัญของสมุดบันทึกเหล่านี้ในฐานะบันทึกรายงานประจำวันที่สามารถตรวจสอบสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นในหอศิลป์ย้อนกลับไปได้ถึงปี พ.ศ. 2534 “ซึ่งมันย้อนแย้งมาก เพราะก่อนหน้านั้นหอศิลป์ เจ้าฟ้าไม่เคยจัดเก็บมันอย่างจริงจัง บันทึกกองนี้เหมือนกับพี่ๆ ที่นั่งอยู่ตามมุมต่างๆ ในห้องจัดแสดงพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ คือพวกเขาเหล่านั้นคือตัวละครสำคัญที่ทำให้พิพิธภัณฑ์เดินต่อไปได้ แต่กลับไม่ค่อยได้เครดิตเท่าไหร่นัก” ธนาวิบอกกับ art4d

“เราเจอมันครั้งแรกตอนปี 2009 แล้วก็รู้สึกว่าบันทึกนี้ที่มีการบันทึกซ้ำๆ กันทุกวันนั้นมีส่วนร่วมในทุกๆ ช่วงเวลากับสิ่งอื่นๆ ในพิพิธภัณฑ์ที่มีความสำคัญระดับชาติ แต่กลับไม่เคยถูกมองเห็นความสำคัญเท่าไหร่” ปรัชญาเล่าถึงกระบวนการทำงานของเขาที่ตั้งใจทำงานศิลปะโดยการ “หยิบยืมสิ่งที่มีอยู่แล้วมาสร้างประกอบคำขึ้นมาใหม่” เพื่อ “เปลี่ยนสถานะของมันจากที่ไม่ถูกมองเห็น ให้ถูกมองเห็น และถูกเวลาพิจารณามากขึ้นกว่าที่เคย” ซึ่งเป็นเหตุผลที่อยู่เบื้องหลังการหยิบเอาไม้กั้นล้อรถมาจัดแสดงร่วมในครั้งนี้ โพสต์แนะนำศิลปินของ BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY เรียกปรัชญาว่าเป็นนักเล่นแร่แปรธาตุตัวยงที่มีกระบวนการทางศิลปะที่แทบจะมองไม่เห็นได้ด้วยตา แต่อีกบทบาทที่เราคิดว่าปรัชญาทำได้อย่างแนบเนียนครั้งนี้คือการสร้างสถานการณ์ ที่ทำให้หลายๆ สิ่งที่ไม่ได้เกี่ยวข้องกันกลับมารวมอยู่ในที่เดียวได้อย่าง (ดู) สมเหตุสมผล

สถานการณ์ที่ชื่อของพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ หอศิลป กับ BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY ถูกเอ่ยขึ้นมาพร้อมกัน ทำให้เรามองเห็นแรงงานล่องหนในระบบแกลเลอรี่เอกชนกับหอศิลป์ของรัฐพร้อมๆ กัน (นี่คงเป็นเหตุผลหนึ่งของการเปลี่ยนให้ห้องนิทรรศการย่อยของ BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY เป็นออฟฟิศ) และการนำสมุดบันทึกประจำวันมาจัดแสดงให้ถูกเปิดอ่าน ก็เป็นโอกาสให้เรามองทะลุ text ไปเห็นคนจดบันทึกข้อความเหล่านั้น กลุ่มคนที่อยู่เบื้องหลังการดำเนินงานของหอศิลป์ หรือกระทั่งนำไปสู่การสังเกตถึงปัญหาของคำว่า “ภัณฑารักษ์” ในพิพิธภัณฑ์ของรัฐ กับ “คิวเรเตอร์” ตัวละครหลักในโลกของศิลปะร่วมสมัย ในขณะที่อาชีพ “ภัณฑารักษ์” ยังมีปัญหากับการขยับขยายบทบาทของตัวเองไปมากกว่าการเป็น “ผู้ดูแลรักษา” สมบัติของชาติ และการผูกติดอยู่กับการทำงานรับใช้ภาครัฐ ไปสู่การทำงานที่มีความอิสระทางความคิด (หรือกระทั่งการวิพากษ์) เทียบเท่ากับบทบาทของคิวเรเตอร์ในโลกศิลปะร่วมสมัย คำว่าคิวเรเตอร์ในปัจจุบันก็เริ่มแพร่หลายจนกระทั่งใครๆ ก็เป็นคิวเรเตอร์ได้ หรือกล่าวอีกนัยหนึ่งคือ ความแพร่หลายทำให้บทบาทของคิวเรเตอร์ถูกลดทอนจนเหลือแต่ความสามารถในการ “เลือก” แต่ไปไม่ถึงการผลิตองค์ความรู้ทางวิชาการด้านประวัติศาสตร์ศิลปะ เห็นได้มากในปัจจุบันที่จะทำอีเวนต์อะไรทีก็เรียกว่า “นิทรรศการ” และการคัดเลือกอะไรๆ ก็เรียกว่าเป็นการ “คิวเรต” ไปเสียหมด

ก่อนที่ Institutional Critique คำอีกคำในบัตรคำจะลอยเข้ามาในหัวเรา (เป็นอีกครั้งที่เสียงของคิวเรเตอร์เข้ามากำกับทิศทางการรับชมงาน) เป็นข้อสรุปของนิทรรศการ มีอีกทางแยกหนึ่งที่น่าสนใจจะแวะไปคิดคือวิธีการใช้ Found object ในนิทรรศการนี้ การหยิบยืมวัตถุมาจัดแสดงของปรัชญามีวิธีการที่น่าสนใจ ที่เห็นได้ชัดที่สุดคือ สี สมุดบันทึกประจำวัน ไม้กั้นล้อ ในนิทรรศการนี้ไม่ได้ผ่านพิธีกรรมการตั้งชื่อให้สิ่งนั้นเปลี่ยนไปเป็นอย่างอื่นที่มันไม่ได้เป็น แต่ปรัชญารักษาตัวตนของมันไว้อย่างครบถ้วน Found object ในครั้งนี้จึงไม่ได้กลายมาเป็นงานศิลปะ แต่เป็นเหมือนกับ “ยานพาหนะให้คนมานั่ง ที่ไม่จำเป็นต้องเดินทางไปตามความคิดของคนสร้างงาน งานศิลปะในมุมมองหนึ่งก็คงเป็นยานพาหนะให้เราออกจากสิ่งที่เราเห็นอยู่ ให้มีภาพอื่นที่ซ้อนขึ้นมา” ปรัชญา บอกกับ art4d ว่า มุมมองของเราต่อสิ่งเหล่านั้นจะเปลี่ยนไป ไม่ว่าจะเปลี่ยนไปตลอดกาลหรือแค่ในช่วงเวลาหนึ่ง หรืออาจจะไม่ได้เปลี่ยนไปเลยก็ได้ขึ้นอยู่กับเราอีกทีหนึ่ง

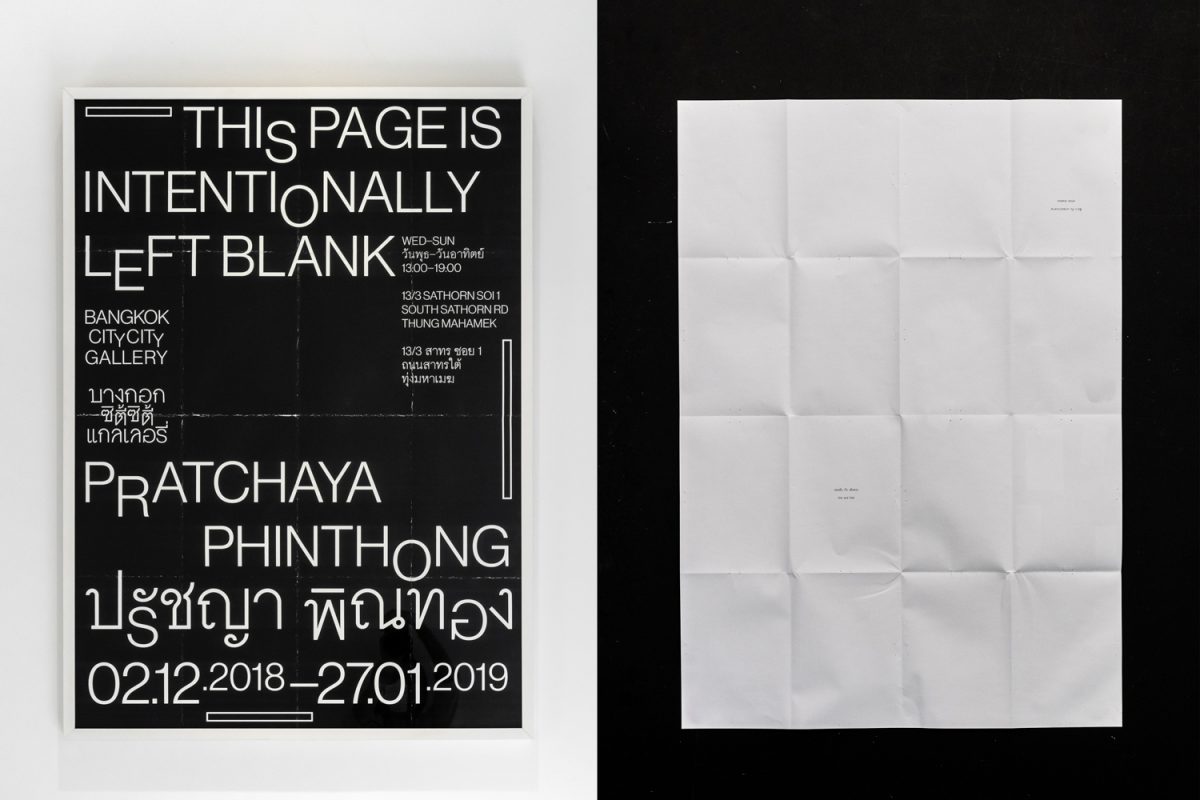

ท้ายที่สุดภาพถ่ายและบทความที่ตีพิมพ์ตามสื่อต่างๆ ก็จะกลายมาเป็น archive ของนิทรรศการนี้ ความที่ทุกๆ อย่างในห้องนิทรรศการจะถูกนำไปเก็บเข้าที่เดิมทั้งหมด บทความและภาพถ่ายเหล่านี้จะเป็นสิ่งเดียวที่ยืนยันการมีตัวตนอยู่ในช่วงระยะหนึ่งของนิทรรศการ สิ่งเดียวที่น่าจะใกล้เคียงกับการเป็นงานศิลปะอาจจะเป็นโปสเตอร์นิทรรศการที่ปรัชญาส่งให้กับผู้ชม (บางคน) ในนั้นมันมีทั้งมูลค่าเชิงเศรษฐกิจที่จับต้องได้ (แสตมป์จำนวน 30 – 40 บาท) น้ำหนัก 0.0060 – 0.00064 กรัม (น้ำหนักของความว่างเปล่าไม่เท่ากัน?) และมูลค่าที่ผันแปรไปตาม “ชื่อผู้รับ”

The entire space is unexpectedly tidy. The walls are left blank (?). Walking out of the main exhibition space, we look into the small exhibition room thinking that there might be something to see there, but it is just the gallery’s office space. We walk back to the main room and notice a floor with a pole as if the boom barrier of 123 Parking nearby was expanding its territory. Then another unusual thing happens. The door at the end of the exhibition room is opened for the first time. We turn back and find a box whose insides are a bunch of daily journals of the National Museum, the National Gallery and word cards, all placed below the eye level near the entrance door. The cards, which are probably the only text material of the exhibition, write words such as Archive, Deconstruction, Found object, Institutional Critique, Performativity, Readymade and White Cube but they are not exactly the kind of artist statement you have seen in any other exhibitions.

The absence of captions and descriptions is what both Pratchaya Phinthong, the artist and Thanavi Chotpradit, the exhibition’s curator, intended to create. These details are set to be released on the last day of the exhibition (27th January), which is also the designated date for the debut of the exhibition’s pamphlet as well as the artist talk activity. Another set of texts is created outside of the exhibition room and referred to as ‘Tracing the Dots,’ an activity in which students of Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University and five writers/artists retrace the history of art museums in Thailand starting off from the National Gallery of Thailand and Bhirasri Institute of Modern Art to BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY. From the activity, everyone is asked to write a collection of articles, which are later published in the pamphlet alongside the essay written by the exhibition’s curator. Two reading sessions took place during the almost two-month duration of the exhibition. The first one had Assistant Professor Dr. Kasem Phenpinant hosting the “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Jacques Derrida, 1995/1996)” reading, which was open to the general public. “An Archival Impulse (Hal Foster, 2004)” by Dr. Sayan Daengklom, however, required participants to read an article beforehand and write down the reasons why they wished to attend the activity. These side activities were held to stimulate ‘conversations’ among viewers before actually experiencing the artist’s perspective. The curatorial direction that eliminates the use of text suggests other possible planes of the way ‘reading’ can be done, which in this case, doesn’t fall into the ‘art viewing’ norms where one examines the details of brushstrokes or emotions expressed through the eyes of a figure in a particular painting. That is what makes this exhibition interesting simply because the first thing we are meant to read is the artist’s intention to create a state of emptiness.

“The exhibition’s poster is like a soft invitation that gets people to look at the emptiness and to see what is actually on the poster, whether that be creases, the color white, straight lines or shadows of colors and light. What’s interesting is how can one notice the existence of a blank space?” Seeing a blank space seems to be the core idea of the exhibition, but such space can only reveal itself under certain conditions. Phinthong explains the creation of a blank space on a page of paper with the phrase ‘this page is intentionally left blank’ commonly used in the publishing industry. He finds it strange that in order for a blank space to be read as blank, it has to rely on the existence of something that both validates and eliminates the emptiness at the same time. With this exhibition, the viewers’ ability to notice the label of the artwork is one of the conditions. The details of the label are deviated from what the phrase (This page is intentionally left blank) is dictating with the way it is designed to not have direct contact with the viewers’ eyes. The standard size of the label allows viewers to be subsumed by the blankness of the wall before it gradually reveals its existence. The title 4SEASONS A1000 confirms that the emptiness one sees isn’t actually empty and that the wall is actually painted using the same color as the walls of the National Gallery of Thailand.

ONE OF BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY’S POSTS INTRODUCES PHINTHONG AS A MASTERFUL ALCHEMIST WHOSE ARTISTIC PROCESS IS ALMOST INVISIBLE. BUT THERE IS ANOTHER ROLE OF THE ARTIST, WHICH IS THE WAY HE ADEPTLY ORCHESTRATES A SITUATION THAT PUT TOGETHER ALL THE SEEMINGLY IRRELEVANT THINGS INTO ONE PLACE AND WITH SUCH A RATIONALE BEHIND THEM

“There are several degrees of painting. It can be told as an ordinary method or elaborated as this very delicate process. White is the essence of all these objects and we use it to push the boundary further, to emphasize an object or idea to visually jump out from the background. White Cube is just an imprisonment of light to create a space and conditions.” Phinthong uses white as a hyperlink that references a term in art history known as White Cube. The jargon, which is found on the curator’s word card, can be traced back to the foundation of power that was first used to determine artistic boundaries back in the early 20th Century in the West and later picked up by local institutions such as the National Gallery of Thailand and eventually the exhibition space of BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY. Additionally, the exhibition of white color as a work of art and the intention for it to be unrecognized at first illustrates Phinthong s artistic approach from the way his work plays with the audience’s expectations, which in this case, is the physical presence of an art object.

This is where the lingering question first asked by the exhibition’s curator makes its way back into our head. “What makes art, Art?” The logbooks are recognized as ‘exhibition objects’ probably for the first time when the artist and curator begin the process of borrowing them for the show. Such status is indicated in the paper submitted for the National Gallery of Thailand approval for the lending and returning of the logbooks. Confused, unsure and somewhat cautious are the reactions of the officers responsible for the logbooks, presumably for not knowing exactly what the artist and the curator would do with them. It is somewhat confirmation of how significant these logbooks are as daily documentation of everything that has been going on in the National Gallery of Thailand all the way back to 1991. “It’s an irony because both the National Gallery of Thailand have never really paid attention to these logbooks or the way they are kept before. These documents represent the people who sit in different corners of the National Museum and the National Gallery of Thailand and how important their role is in these institutions’ operations while rarely being given the credit they deserve,” said Chotpradit to art4d.

“We came across them for the first time in 2009 and felt that the logbooks, which are documented on a daily basis, actually share their existence with many other historical artifact. And all the while, these documents are rarely recognized.” Phinthong talks about the working process, in which he intends to create art by “borrowing what’s already there to form new meanings” to ‘transform its neglected status into something that will receive more consideration.” These ideas and intents are behind the use of a car stoppers as a part of the installation. One of BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY’s posts introduces Phinthong as a masterful alchemist whose artistic process is almost invisible. But there is another role of the artist, which is the way he adeptly orchestrates a situation that put together all the seemingly irrelevant things into one place and with such a rationale behind them.

The situation where the names the National Gallery of Thailand and BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY are mentioned at the same time enables us viewers to acknowledge the invisible forces within the systems that propel the private and state-run galleries (and perhaps one of the reasons why BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY’s small exhibition room is turned into an office). Exhibiting these logbooks and allowing them to be opened and read is a chance for one to look through the text and see the people who wrote them. It goes so far as to make an observation of the problematic issue over the term ‘curator’ in the Thai’s state-run museums and the ‘curators’ who have become a key figure in the world of Contemporary Art. While curators (in state-run museum) still face the dilemma of not being able to expand their role into something more than a ‘caretaker’ of national treasures or someone who works to serve the state, their freedom of expression (or even the freedom to criticize) should be deliberated to be equal to that of curators in the contemporary art world. The truth of the matter is, the title curator has been so widely used that we have reached a point where anybody can be a curator. In a way, the more popular the term becomes, the role of curators is lessened to the ability to ‘choose’ but not be able to produce substantial academic knowledge in the realm of art history. Such a tendency can be seen in emerging social events that are referred to as ‘exhibitions’ and the use of the term ‘curate’ with practically every type of selection or organization process.

Before ‘Institutional Critique,’ another word on one of the cards, finds its way into our brain (marking another occasion where the curator’s voice directs the viewing experience) and serves somewhat as the conclusion, there is another interesting crossroad for viewers to take and contemplate the use of found objects in this exhibition. There is something interesting in the way Phinthong borrows the exhibited objects and the most obvious observation is the fact that the color, the journals and boom barrier displayed in the exhibition have not really been through the renaming process. Nothing is given new meanings or statuses that will turn them into something they are not. Phinthong keeps the identity of these objects intact. In this exhibition, Found objects are not transformed into art but more of ‘vehicles that transport people into directions that do not necessarily have to be the same as the ones provided by the artist or curator. Art, in a sense, is a vehicle that takes us away from what we usually experience and to see new images that are created.” Phinthong tells art4d that our perception towards these things will change. It might take forever, or a certain period of time or it may not change at all, depending on our own take as a viewer.

Ultimately, the photographs and articles that have been published in different media outlets will become an archive of the exhibition itself. Once all the objects are returned to their places of origin, only the written works and photographs can confirm its temporary existence. The only thing that is the closest to being considered an artwork from the exhibition is its posters, which Phinthong managed to have delivered to some members of the audience. Carried with them are tangible economic values, from the prices of postal stamps (THB 30-40) varied by the 0.0060-0.00064 gram weight of the posters (unequal weights of emptiness?), to the value attached to the ‘names of the recipients.’