THE “ANONYMOUS SIGNS” IN BANGKOK, WHICH IS LED TO THE OBSERVATION THAT THE CRACKS OF TIME WE FIND IN A MUSEUM CAN ALSO BE FOUND IN AN URBAN SPACE AS WELL

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

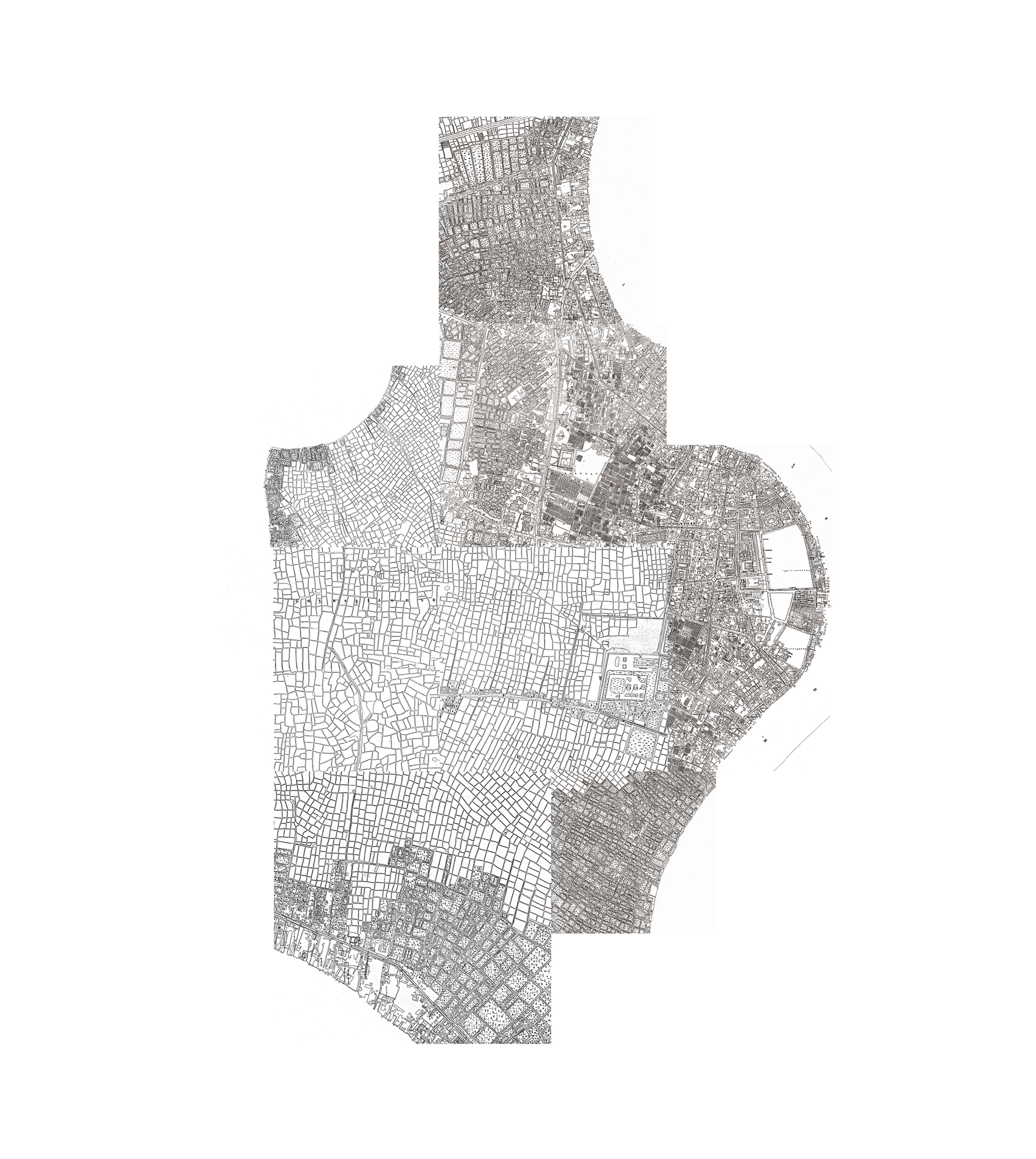

ILLUSTRATION BY WASAWAT DECHAPIROM, THE REARRANGEMENT OF 1887 MAPS OF BANGKOK

(For English, please scroll down)

ในบรรดาป้ายทั้งหมดบนท้องถนนในกรุงเทพมหานคร ผมอยากเขียนถึงป้ายชนิดหนึ่งที่ไม่จำเป็นต้องมองก็ได้ มันไม่มีฟังก์ชั่นกับการใช้ชีวิตประจำวัน ไม่ได้มีส่วนร่วมในการนำทางคนไปสู่จุดหมายปลายทาง และไม่มีไฟส่องให้อ่านตอนกลางคืน ป้ายที่ว่านี้มีสีน้ำตาล ขนาดใหญ่พอจะใส่ข้อมูลภาษาไทย – อังกฤษไว้หน้าเดียวกัน ข้อมูลบนป้ายบอกเล่าประวัติศาสตร์การก่อตั้งของสถานที่อย่าง วัดวาอารามหลวง วัง ถนน สะพานเก่า หรือชุมชนโบราณ ผมยังสืบไม่พบว่าป้ายนี้เกิดขึ้นจากโครงการของผู้ว่า กทม. คนไหน กระทั่งมีชื่อเรียกอย่างเป็นทางการว่าอะไร แต่เดาได้คร่าวๆ ว่ามันคงมีจุดประสงค์ในด้านการเผยแพร่ความรู้ทางประวัติศาสตร์ และคัดแยกพื้นที่ประวัติศาสตร์ออกจากพื้นที่ทั่วไปในเมือง ผมจะขอตั้งชื่อป้ายดังกล่าวในบทความนี้ว่า “ป้ายนิรนาม”

ในบทความ Of Other Spaces: Utopia and Heterotopias (1967) นักคิดผู้บุกเบิกกระแสโครงสร้างนิยม Michel Foucault เสนอวิธีการอ่านพื้นที่ต่างๆ ไว้อย่างน่าสนใจ โดยเฉพาะมุมมองการรับรู้ที่เขามีต่อพื้นที่ซึ่งไปไกลมากกว่าการนิยามตามกิจกรรมที่เกิดขึ้น อย่างเช่น พื้นที่การเดินทาง – ถนน สถานีรถไฟ หรือพื้นที่ส่วนตัว กึ่งปิดกึ่งเปิด เช่น บ้าน ห้องพักในโรงแรม Foucault เสนอแนวคิด Heterotopia พร้อมกับคำอธิบายที่ค่อนข้างเปิดกว้างไว้ว่า หาก Utopia หมายถึงพื้นที่ที่ทุกๆ อย่างสมบูรณ์ Dystopia คือพื้นที่แห่งความแหว่งวิ่น Heterotopia นั้นก็คือพื้นที่ที่อยู่ “ระหว่าง” และยกตัวอย่าง รายชื่อพื้นที่ที่เข้าข่ายการเป็น Heterotopia ไว้จำนวนหนึ่ง (โรงพยาบาลบ้า โรงแรม ป่าช้า ฯลฯ) Heterotopia ถูกอ้างถึงอยู่อย่างสม่ำเสมอ ไม่ว่าจะในหมู่นักวิชาการด้านปรัชญาและนักทฤษฎีเมือง

Foucault พูดถึงพื้นที่พิพิธภัณฑ์ไว้ว่าการรวบรวมสิ่งของหลายชนิดจากหลากศตวรรษ และการจัดแสดงในพื้นที่ปิดทำให้ “เวลา” ภายในพื้นที่ไม่หยุดนิ่ง มีลำดับเวลาแตกต่างจากพื้นที่ภายนอก และมี sense of place ต่างไปจากพื้นที่อื่นๆ ผมคิดว่าความจริงข้อนี้ไม่ได้เปลี่ยนไปจากเดิมมากนัก (ถึงแม้ Foucault จะพูดเอาไว้เมื่อกว่า 50 ปีก่อน) ทุกคนเคยไปพิพิธภัณฑ์ และหลายคนก็คงเคยรู้สึกว่าการเดินจากห้องหนึ่งไปอีกห้องในพิพิธภัณฑ์ให้อารมณ์คล้ายกับการเดินผ่านทางลัดที่พาเรากระโดดข้ามเวลาจากยุคหนึ่งไปอีกยุคหนึ่ง ปฏิเสธไม่ได้ว่านอกจากการจัดการของภัณฑารักษ์ วัตถุเป็นปัจจัยสำคัญที่ส่งผลต่อพื้นที่และการรับรู้พื้นที่เช่นกัน และหากยึดตามตรรกะแบบที่ Foucault เสนอ พื้นที่เมืองก็คงไม่ต่างอะไรกับพื้นที่ในพิพิธภัณฑ์ เพราะมันเองก็เช่นกันที่เป็นภาชนะรวบรวมสถาปัตยกรรม วัตถุ คน กิจกรรม และเหตุการณ์ จากหลายยุคหลายสมัยไว้ในที่เดียว

ผมคิดว่ากับพื้นที่เมืองเอง หน้าที่ตรงนี้คงหนีไม่พ้นรัฐ พื้นที่สาธารณะในกรุงเทพฯ แทบทั้งหมดเกิดขึ้นโดยรัฐทั้งสิ้น ย้อนกลับไปดูในประวัติศาสตร์ การตัดถนนครั้งแรกทำขึ้นในช่วงรัชกาลที่ 4 ตามการร้องขอของชาวตะวันตกภายใต้เงื่อนไขสิทธิสภาพนอกอาณาเขต การตัดถนนรอบวังหลวงมีไว้เพื่อกั้นพื้นที่ระหว่างพื้นที่ไพร่กับกษัตริย์และป้องกันอัคคีภัย การตัดถนนเส้นต่อๆ มา ที่ขยายตัวไปทางเหนือและทางตะวันออกของกรุงเทพฯ เกิดขึ้นมาเพื่อเชื่อมต่อเส้นทางระหว่างวังสู่วัง ส่วนถนนที่เอกชนเป็นคนตัด ก็มักดำเนินการโดยกลุ่มชนชั้นนำที่ใกล้ชิดกับผู้ปกครอง ที่ตัดขึ้นมาเพื่อแบ่งขายเอกชนเจ้าอื่นเก็งกำาไรพื้นที่ ส่วนพื้นที่สาธารณะจริงๆ ที่เรามีอยู่ตอนนี้ ก็เรียกได้ว่าไม่ใช่พื้นที่ที่สามารถทำกิจกรรมแสดงออกอะไรได้มากเสียเท่าไหร่ เพราะหากประวัติศาสตร์เรื่องไหนที่มีประชาชนเป็นตัวละครหลัก ถ้าใครตามข่าวช่วง 2-3 ปี นี้ ก็คงจะทราบกันดีว่า หมุดหมายทางประวัติศาสตร์ประชาธิปไตย (หลายแห่ง) ของเราทยอยถูกถอดถอน และบางแห่งก็แทนที่ด้วยเทศกาลส่งเสริมความเป็นไทยแบบเปลือกๆ ที่เกิดขึ้นมารับกับกระแสละครไทยย้อนยุค

การควบคุมเรื่องราวของพื้นที่โดยภาครัฐยังมีอีกหลายรูปแบบ อย่างไรก็ตาม ถึงเวลาแล้วที่จะกลับมายังประเด็นหลักของเรา “ป้ายนิรนาม” ที่กล่าวถึงข้างต้นโดยมีทุนรอนบางอย่าง ป้ายนิรนามน่าจะเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของกระบวนการควบคุมความทรงจำของพื้นที่ ให้เรื่องราวที่ไหลกลับมายังปัจจุบันเป็นเรื่องชุดที่ทางการต้องการ แต่ป้ายนี้ทำงานต่างออกไป ผมคิดว่าสาเหตุที่มันไม่เข้าพวกกับป้ายตามแหล่งโบราณสถาน (ลองนึกถึงภาพจังหวัดพระนครศรีอยุธยาประกอบ) มีอยู่ 2 ข้อใหญ่ๆ หนึ่งคือ มันไม่ได้ตั้งอยู่หน้าพื้นที่ทางประวัติศาสตร์ที่มีภาพลักษณ์ในแบบฉบับของพื้นที่ทางประวัติศาสตร์มากพอจนเราเองจะสามารถรับรู้ถึงความสำคัญทางประวัติศาสตร์ของมันได้ก็ต้องอาศัยเนื้อความของป้ายข้างต้นนั้นต่างหาก ป้ายที่ว่านี้จึงไม่ใช่คำบรรยาย “ประกอบ” หรือคำอธิบาย “เพิ่มเติม” ให้แก่ภาพ ถ้าให้นึกว่ามันเหมือนกับอะไร ผมคิดว่าคงเหมือนกับป้ายคำบรรยายของเศษจานแตกๆ หักๆ อันหนึ่งในพิพิธภัณฑ์ ที่สำหรับคนที่ไม่เข้าใจเรื่องการอ่านร่องรอยที่อยู่นอกเหนือการสื่อสารด้วยข้อความภาษา หากไม่ได้ป้ายมาบอกก็คงไม่รู้ว่ามันเป็นโบราณวัตถุ

ช่วงขณะสั้นๆ นั้นเอง เป็นจังหวะที่เราจะเจอเข้ากับ “เวลา” ก่อนที่จะถูกนิยามให้เป็นประวัติศาสตร์

กลับมาที่ข้อสอง ป้ายที่ว่านี้ไม่ได้ตั้งประจำอยู่กับแค่พื้นที่เชิงสัญลักษณ์ อาคาร หรือสถานที่ที่อยู่ในการรับรู้ของคนทั่วไป แต่ตั้งอยู่เงียบๆ ทั่วกรุงเทพฯ โดยไม่ได้มีตรรกะการวางตำแหน่งที่ชัดเจนมากพอให้เดาได้ว่าต้องเดินไปตรงไหนจึงจะพบ ครั้งหนึ่งผมพบป้ายประเภทนี้ ตรงเชิงสะพานหน้าตาธรรมดาแห่งหนึ่ง ข้างๆ ท่าเรือสะพานผ่านฟ้าลีลาศ (ย้ำว่าไม่ใช่สะพานผ่านฟ้าลีลาศ) ก่อนจะพบว่าลวดลายปูนปั้นตรงราวกันตกของสะพานที่ผมเดินผ่านอยู่บ่อยๆ นั้นมีที่มามาจากเหตุการณ์สวรรคตของรัชกาลที่ 5 ผมเดินย้อนกลับไปดูอีกครั้งและพบรูปปั้นผู้หญิงอุ้มเด็กร่ำไห้ตามที่ป้ายเขียนไว้จริงๆ นั่นเป็นครั้งแรกที่ผมเห็นการมีตัวตนของเธอ

อ่านบทความฉบับเต็มได้ใน art4d No.266

Illustration by Wasawat Dechapirom, the rearrangement of 1887 Maps of Bangkok

Of all the signs in the streets of Bangkok, there is one particular type of signs that I would like to talk about. There’s no need for us to look at them. They do not have any specific function in our everyday life. They don’t contribute anything to providing people’s directions. They are not given any light for better visibility at night. These signs are brown in color. They’re big enough to fit a portion of both Thai and English text. They contain information about the histories behind establishments of temples, castles, ancient communities, streets, historic brides, etc. I haven’t really found the origin of the signs and under which administration of Bangkok governor or project they were conceived. I don’t even know the proper term used to call them. My wild guess is that they are intended to provide and promote information about the city’s historic site, consequentially separating these areas from other parts of the city’s fabric. For this article, they will be referred to as the anonymous signs.

In his essay, Of Other Spaces: Utopia and Heterotopias (1967), the pioneering thinking of Structuralism movement, Michel Foucault interestingly proposes ways spaces can be read. With his perception and take on physical spaces, which are not defined by activities they are used for or recognized by (traveling space-streets/train stations, private or semi private spaces such as homes and hotel rooms), Foucault proposes the concept of Heterotopia with a rather broad explanation. If Utopia were to be the place where everything was perfect and Dystopia was the opposite of it, Heterotopia would be the space in between. Foucault created a list of spaces that can be categorized as Heterotopia (mental institute, hotel, cemetery, etc.), while the term itself has been frequently cited by academics and scholars of philosophy as well as urban theorists.

Foucault defines museum as a collection of artifacts from different centuries, which are exhibited in a closed space, allowing the ‘time’ within the space to constantly move in a different order from the outside world. Museum possesses a different sense of place. To me, this is the fact that hasn’t changed much (Foucault wrote this 50 years ago). I assume that everyone used to go to a museum at least once, and many must have felt that walking from room to room inside of a museum’s space is a similar experience to taking a detour from one particular era to another. It’s undeniable that apart from the curatorial approach, exhibited objects play significant effects on the space and the way it is experienced. If we were to take what Foucault proposed as the logic, urban space isn’t really that much different from a museum space for it, too, is a large container holding architecture, objects, people, activities and incidents from various time periods all within its physical boundary.

For urban spaces, the role and responsibility over the way they are curated inevitably belongs to the state. Almost all public spaces in Bangkok are conceived by the state. Looking back into the history of the city, the first street was constructed during the reign of King Rama IV, following the demand of and extraterritorial rights of the citizens of western nations residing in the country at the time. The roads built around the Grand Palace served as a barrier that separated the court’s territory from that of the commoners, and prevented damages in the case of fire. The road construction continued towards the north and east of the city, mainly to connect the King’s palaces together. The road construction carried out by the private sector was mostly funded by the elites with close ties with the ruling class. The lucrative opportunity that ensued includes escalating land price; the benefits that had been shared among other private operators. The actual public spaces the people have in their hands rarely serve as spaces that offer much freedom in terms of the activities that are allowed to take place. For those who have been following the news would know that every story of every place in the history where the people are the protagonist, especially places that embody the milestones in the history of democracy in this country, have been torn down, erased and in some cases, replaced by the superficial display of cultural values inspired by a popular soap opera.

The state’s control over public space comes in many shapes and forms Nevertheless, it’s time we come back to the main topic of our discussion, the ‘anonymous signs.’ The signs, with certain assets of their own, are possibly a part of the process created to control memories of a space. The stories make their ways back to the present time are the set of narratives selected and allowed by the state. But these signs work differently. There are two major reasons why I think these signs do not fit in all that well with the signs at these ancient remains (imagine the ancient temples of Historic City of Ayutthaya). Firstly, the signs are not located in front of historical places, which contain a clear enough image of the kind of historical place we know of or are familiar with. We know of their historical significances from those signs. This makes the signs something more than just captions or additional descriptions. If I were to think about what they remind me of, it would be the caption of a broken piece of utensil in a museum. For those who do not have the knowledge in the traces and details of the object, the text is the only explanation that allows them to recognize and understand the displayed item as an archeological find.

IT IS DURING THIS BRIEF PERIOD OF TIME

THAT ONE COMES ACROSS WITH ‘TIME’

BEFORE IT IS DEFINED AS A PART OF HISTORY

The fact that the signs are not presented only in the symbolic spaces, buildings or places that can be recognized by the general public, but standing silently across Bangkok, there isn’t any logically planed pattern that allows us to speculate where can such signs be found. I once stumbled across this type of sign at a normal looking bridge near Phan Fa Lilat boat station (the bridge isn’t Phan Fa Lilat bridge), which led me to discover that the origin of the ornamental details of the concrete work of the balusters of the bridge I walk pass all the time is actually the passing of King Rama V. I walked back to the bridge and saw the details of the sculpture of a woman carrying a baby in her arms, crying, just like it’s said in the sign. I recognized her existence for the first time.

Read the full article in art4d No.266