NOT ONLY WORKING ON DRAWINGS OR 3D MODELS, BUT CHAING MAI-BASED STUDIO, SHER MAKER ALSO CONCEIVES ARCHITECTURE THROUGH MATERIAL EXPERIMENTATION, UNDERSTANDING OF CLIENT AND CONTEXT, AND COLLABORATION WITH LOCAL CRAFTSMEN

TEXT: PICHAPOHN SINGNIMITTRAKUL

INTERVIEW: KARJVIT RIRERMVANICH AND PAPHOP KERDSUP

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHER MAKER

(For Thai, press here)

Sher Maker is a Chiang Mai-based design studio with projects that are now gaining international recognition, especially the design of their own workspace that was recently awarded Interiors Project of The Year from Dezeen Awards 2021. art4d talks with Patcharada Inplang, one of the co-founders about how Sher Maker has been connecting the dots between Chiang Mai, local artisans, builders and their very much practice-oriented design process; the elements that have collectively contributed to the evolution of their quintessential body of work we’ve seen in the past 2-3 years.

Thongchai Chansamak (Left) and Patcharada Inplang (Right)

art4d: Why Chiang Mai?

Patcharada Inplang: We look at two things. The first is our innate connection with nature, which essentially led us to ask ourselves this simple, fundamental question that if we could choose what type of city would we want to live in, what would it be like?. Thongchai Chansamak or Oat (another co-founder), and I weren’t born in Bangkok and we’ve never really wanted to live in a big city. We wish to be close to nature. It may sound very idealistic but we believe that the space we surround ourselves in has significant impacts on how we think and work. It’s important, at least to us. We also think that Chiang Mai is a city with a great potential to be this haven for creative professionals. It’s the city that has the right environment for a design practitioner because it has its own cultural background and it has always welcomed small, non-Bangkok based studios to experiment and perform ideas they find interesting. I think its mainly these two factors why we chose Chiang Mai as our base.

art4d: Looking back to when you first graduated, what was happening before you decided to relocate to Chiang Mai?

PI: Oat went to Chiang Mai University, studying architecture while my background includes having my own crafts brand with the production and studio based in Chiang Mai. After I graduated, I worked with Studiomake for two years and that really gave me an opportunity to gain experiences working in the design studio that really focuses on the practice and creating aspects of design. It was one of the most eye-opening experiences in my life. It was the period when I was a student entering the practice fields, and there was a lot to learn. I later decided to move back to Chiang Mai, which I consider to be an entirely new starting point of our professional career, literally from square one, because neither of us were Chiang Mai natives but are people who chose to live and work here.

Sher Maker Studio

Sher Maker Studio

art4d: What was it like in the beginning, setting up your studio in Chiang Mai?

PI: During the first two years, we were working on projects just like any other design studios would normally do. But because of the fact that we both thought that our architectural ideation and language wasn’t all figured out, it was pretty much a period of trial and error, so it took us a lot of mental and physical effort to finish a project. There was also a period where we stopped working, and during this gap year, we were working out what we actually wanted to do, and contemplating how we want to live and work. We didn’t work on any designing any houses or buildings at the time, until we were asked by our friend to help renovate a hotel, which led us to meet a team of builders who become the people we have been working with until now, as Sher Maker.

The project that we consider to be the actual first step for Sher Maker and this team of builders is the Lan Din project. I remember it being very challenging because not only was it the first project we got to really work together with them, but the design was also finalized with a steel structure and our builder team worked predominantly with wood, they’re carpenters. So it was the first time we got to experiment all these different methods with the team. And it was very collaborative. Whenever each of us encountered a problem, we would discuss, work things out, and find solutions together, one problem at a time.

Lan Din Project

Lan Din Project

art4d: Have the builders always been a part of the design since the first project?

PI: With Lan Din, there was barely anything you would find in a normal design process. It was very close to becoming a full-on self-built architecture. I remember talking to the client about the steel frame and structural design and beauty wasn’t even mentioned (laugh). We just talked about how it would be constructed. It was purely a case of working under financial limitations and discussing how much things would cost us if we built them, and how they would financially burden the project’s owner. We talked about the materials’ geometric and economic orders, and how much time we would have to finish everything without causing the builders to suffer a loss, and about things that were happening right in front of us and how they would turn out. It was the first time we discussed a project without using any preliminary design. It was also us trying to observe expectations and outcomes of the building through this type of work process.

art4d: What can your team of builders do?

PI: Pretty much anything. But they have their own sub-contractors who work in their own ways; for example, they have different teams responsible for steel structures, partition walls, wet works, or other general structural works. All these things are under the supervision of the man we call uncle. But he isn’t a contractor but more like the head builder and he’s the one taking briefs from us, and we would discuss things we want to experiment on. He isn’t on our payroll or anything. We think of these people as the building team who contribute as a part of Sher Maker so to speak, because our contributions to each project are practically equal.

The North uses the word ‘Sala’ for skilled builders or artisans who’re a master in their crafts. Carpenters here are called ‘Sala’, it’s sort of like the term used to honor their skills. But we simply call him uncle. There’s no need for unnecessary flattery between us (laugh).

Personally, I think the people who are makers and builders should be honored and that honor should be something the design industry normalizes. It isn’t like you inspect a construction site and you treat them differently from how you would normally treat your clients. I frankly find that kind of discrimination disgusting. These makers and builders are the people who turn ideas and rendered images into reality with their own hands. I think we need to respect and appreciate everyone equally.

art4d: If the process is about practice-oriented design where design is materialized through actual practice, where do design-related decisions, especially in the aspect of architecture, lie in the entire process?

PI: It’s always been a part of the process since the very beginning. One of the observations we’ve made from this approach to design is collaborative decision making. So, before any decisions are made, we choose to explain it to people from different disciplines and practices, creating a mutual understanding first. Our methodology unifies the entire process from designing to construction into one narrative. So, when we talk to a client or the builders, it’s the same story that everyone can immediately understand. The story isn’t divided into interior or exterior, or structure, or walls. Everything has to be perceived and understood as one unified story. It sounds like a risky method but it is our method that we want to try out. Normally, it’s possible because it’s the contract that combines design and construction together, so the process by itself requires us to make an extra effort managing the construction aspect of it, in addition to design.

PTT Saraphi Project

PTT Saraphi Project

art4d: If that is the case, is the process still applicable if it isn’t used with a project you oversaw the construction yourself?

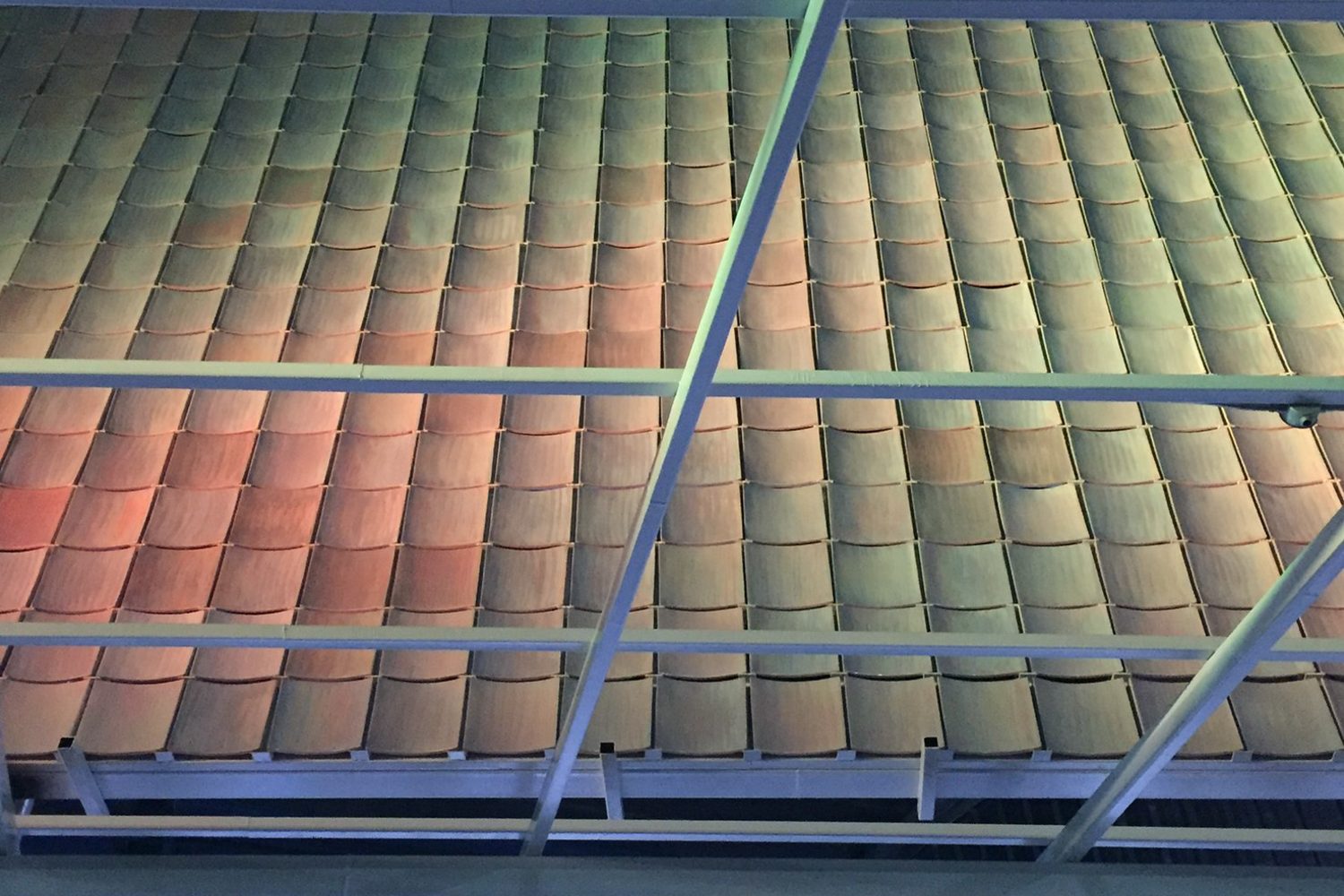

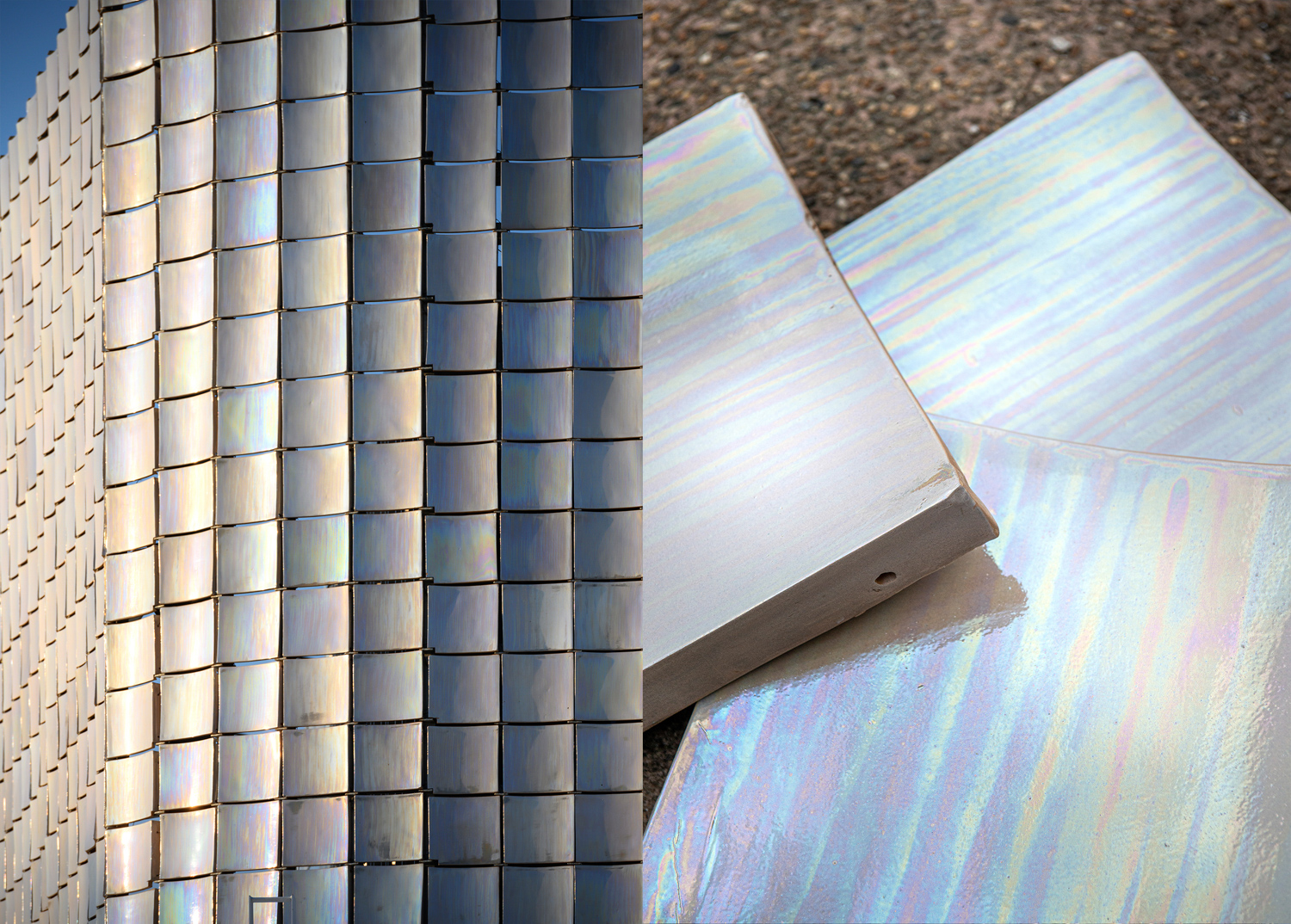

PI: There are a lot of projects whose construction wasn’t carried out by us, especially the ones that are not in Chiang Mai. Some are situated in other provinces such as Surat Thani, or large-scale projects such as the one we did for PTT, which also didn’t use our contractor. But if they’re small to medium scale projects, we try to handle the construction ourselves, because by nature, they’re more fun. But if you’re talking about the design process, it’s the same method. We usually design a material mock-up from the early stage of the design. For example, with some of the projects where we were interested in using Chiang Mai earth as the material for the ceramic components, or the study of the colors and all these different experiments, the experimentation is carried out from the beginning. If it was a project where we didn’t oversee the construction, we’ve discovered that it is our homework to find a way to treat the design of, for example, a house whether it’s the construction methods, materials or architectural language, as this one unified story. We have to allow our clients to be a part of the decision making process, which is a very normal approach that every design practitioner should do. It has nothing to do with working exclusively with our team of builders to achieve the outcome that we have.

PTT Saraphi Project

Another thing is we choose to discuss things based on the fundamental properties of the materials so that a project’s owner can understand the spatial experiences of their project, even just roughly. We may present some isometric or SketchUp renderings with actual materials we use with the mock-ups when we talk to them. For example, if we were asked to design a facade, we would go in with a mock up. This will be one of the things we include in the design process, offering clients a rough but tangible image of how the design could look like, how the facade would envelope the building and the overall feeling it would bring.

I think one of the main issues in design-related communication is creating a mutual understanding while not spoiling your clients. By spoiling, I mean we don’t comply with the owner’s every desire. We want them to understand the process of how a building is born, and that is a kind of collective experience humans can have. For better or worse, we should stick together, learn together, not pay money in exchange for a service and call it a day. If that’s what you want, it will be easier to buy a house from a housing estate project. Also, by spoiling, I mean revealing everything about the building to the owner even before the construction even takes place, like presenting them with realistic renderings of everything to the point where they know and are familiar with every part of the design. We would avoid that if we could and if a project allowed us to because that’s a loss of a sense of discovery and the excitement of building and having something, including the gradual growth the client would get to experience with the architecture. It’s like revealing the end of a movie because you’re afraid to confront new things and new possibilities in life. And we don’t want to do that type of work and we don’t want our clients to have that type of experience. I think architecture is a creation you experience. It isn’t just a residential product. And I think the thought process is a part of all these things.

PTT Saraphi Project

art4d: It’s like the design process the studio uses automatically impacts how materials are developed?

PI: Most of the time, we tend to think about that since the first scheme, what to use and so on. If it’s a dense wall a client wants, we will think about what material is going to be used, and what will the final outcome look like, and we will talk to the client right then and there. We won’t pull options from SketchUp and play around with different possible ideas of using them. We want to get the job done from the beginning, and we don’t like doing a collage where we present all these luxurious, expensive materials. That kind of approach is limiting and it’s an insult to the client.

Wood and Mountain Project

Wood and Mountain Project

art4d: How do you communicate the mood and tone, which is something we find to be a very strong commonality of your projects, to your clients?

PI: Our understanding is that architecture is something that will be created and exist in any part of the world. So when the mood and tone is very abstract, our approach is to talk to a client, asking them about their opinions on the site. Even with rendered images, if they don’t end up understanding the site and space, we might not be able to reach a mutual understanding or we could end up seeing things differently. We don’t tell our clients how good a site is going to turn out, or how beautiful or bright a space is going to be. We’ve never tried to be highly persuasive with our clients but we try to get them to understand their own spaces. If at the end, they told us they couldn’t imagine what the work would look like, because it was too abstract, we could try telling them to think about certain things. We’ll talk to them; think with them until we all reach that point of mutual understanding. Talking with clients this way isn’t a one-way communication but an invitation to form a narrative together through the environment and context surrounding the site.

Khiankhai Home

Khiankhai Home

We used to question what a good design actually is. I’m not saying what we’re doing is something that can defined as a good design. We’re still far from that and we still have more training and learning to do. But from my current perspective, a design practitioner needs to have the human qualities, and they’re not about morality or something along that line. Being a designer with human nature is having the ability to pick up on things that are related to people’s lives, psyches, senses and empathy, and connect them to humans’ experiences through design. I think these qualities are what differentiate a human being from a Pinterest algorithm. With architecture, if you’re able to understand the surrounding conditions and atmosphere, and use them as an element in your work, people who experience your work or the space you create can sense that there’s something special in it.

Khiankhai Home

art4d: We understand that the scale of projects you’re working on have gotten bigger and employing more staff can mean that you’re less hands-on with each project, does that change your material practice in some ways?

PI: That’s an interesting question. We’ve had a chance to talk to a number of architects in Chiang Mai about how they run their offices, both the front and the back of house operations. We do understand that having more staff working for us can contribute to certain changes in our design, causing it to be different from what it used to be, because we’re leaning towards the design service or the more business side of the practice. At the moment, we plan for our office to have a limited number of staff and we pick projects based on our interests, which includes the scale of the work as well. Even though we’ll have to hire more people according to the bigger scale of projects we’ll work on, at the moment, we want to remain the same. It’s really been our intention to work this way, with a team that is very agile, and the balance that allows us to have a healthy personal life, hobbies, to read books we want to read, and to travel, so that we can really live our lives. So, we are currently keeping the studio at this size and we only work on projects we’re really interested in doing.

art4d: Back to the city you live and work in, what is the current scenario of the architecture and design industry in Chiang Mai, from your perspective?

PI: I think Chiang Mai is home to a large number of alternative studios, whether they’re architecture studios or makers from various disciplines. It’s the city whose residents, at least a good number of them, are very obsessed and passionate about their interests. We want to see more potentials from these people who are doing all these different things they are so incredibly passionate about. We see ourselves as global citizens. Whenever we work or study about something, we always wear the lens of a world citizen who lives in a local area. This sets the standard for our works, making them a part of the world, instead of just this small community, making money from locals but never being a driving force for or acknowledging other little people in the way that can nurture the kind of environment that will collectively benefit the design community in general. We get frustrated when we see governmental organizations hand out superficial, perfunctory support to design-related projects, wasting away our tax money when they actually have the money and the power that could have made things better a long time ago.

art4d: What about Bangkok?

PI: Bangkok is a good city. If you really think about it. What other countries in the world have this much centralized development of public transportation system in one city while people living in that city still have to avoid tripping over some manholes or pipelines on pavements. I’m envious. While living in Chiang Mai, if I have to go somewhere, driving my own car is the only option. That’s why I’m saying that Bangkok is a good city. But it will be better if the city allows the young generation citizens to rise above this environment that does nothing but diminish their hopes and dreams. Good luck, though.