ART4D SPEAKS TO ANON CHAWALAWAN, A FOUNDER OF THE MUSEUM OF POPULAR HISTORY WHO RECORDS A POLITICAL MOVEMENT OUTSIDE THE MAINSTREAM NARRATIVE BY COLLECTING OBJECTS THAT SEEMS RATHER CONVENTIONAL BUT ARE PACKED WITH THE ENDEAVOUR OF ORDINARY PEOPLE

TEXT: PRATCHAYAPOL LERTWICHA

PHOTO COURTESY OF KINJAI CONTEMPORARY except as noted

(For Thai, press here)

These past recent years is a period where Thailand has been seeing a rise in political interest from its citizens’. mobdatathailand.org, the website that has surveyed and followed all the ‘mobs’ in Thailand reveals that in 2021 alone, there have been 1,516 protests in 70 provinces.

While the seismic effects generated by these movements are still very much palpable, stories behind these demonstrations vary and can disappear overtime without proper documentation.

To keep these stories from being forgotten and disappearing from the history, Anon Chawalawan decided to start a project call Museum of Popular History. This is a museum with no rooms, no building but it is based mainly on the Facebook page and website of the same name where collections of objects and memories from past and present demonstrations are kept and displayed. The history it is documenting reminds us to never forget what we, as a country, have been through.

After its large-scale, debut exhibition at Kinjai Contemporary in March of 2022, we had a chance to talk with Anon in hopes of knowing more about the Museum of Popular History he founded and its first ever exhibition. Through our conversation, we learn about his belief that has driven him to bring this project to life.

Our dialogue took place in a noiseless room, filled with sounds of the battles of the people, uttered from the objects Anon has saved over the years.

art4d: What is the origin of the Museum of Popular History?

Anon Chawalawan: I majored in history when I was in college and I saw how history of politics I studied revolves around iconic figures; the rulers whether it be the kings and the elites. When the country transitioned into the new political system, you were taught about prime ministers and the military figures so you ended up only knowing this specific group of people, and what they did.

Then I started to wonder about the history of the common people and why it was never documented properly. The National Museum or museums in all the provinces in this country talk about cultures, food, ways of life but never exhibits anything surrounding the political aspect of local communities and people.

Anon Chawalawan l Photo: Pratchayapol Lertwicha

art4d: What do you mean by political aspect?

AC: I mean political movements of people in a certain area or locality, their involvement in politics because rulers and all these so-called important figures could not have taken this country anywhere without the people, the labor force and so on.

Take Khon Kaen, for example, during the The Boworadet rebellion purge, the public prosecutors there played a significant role in this particular part of the history. There were on a plane that landed near Sanam Luang to warn the People’s Party that there was a rebellion happening. But this story is nowhere to be found in Khon Kaen’s provincial museum even though it’s the type of story that is directly related to the history and politics of the country, and on a large scale as well.

art4d: That’s how you got the idea for the Museum of Popular History.

AC: Yes. Like if ten years from now, the government finally passed the same-sex marriage bill and there was no documentation about it, we would never know that, before the bill was passed, the feminist groups had to go through countless protests and activities, or what their campaigns were. So I had this idea that we should archive these movements and what they have done so that stories of the normal people can be included in the history of this country.

art4d: Why do you choose to document these movements through collected objects?

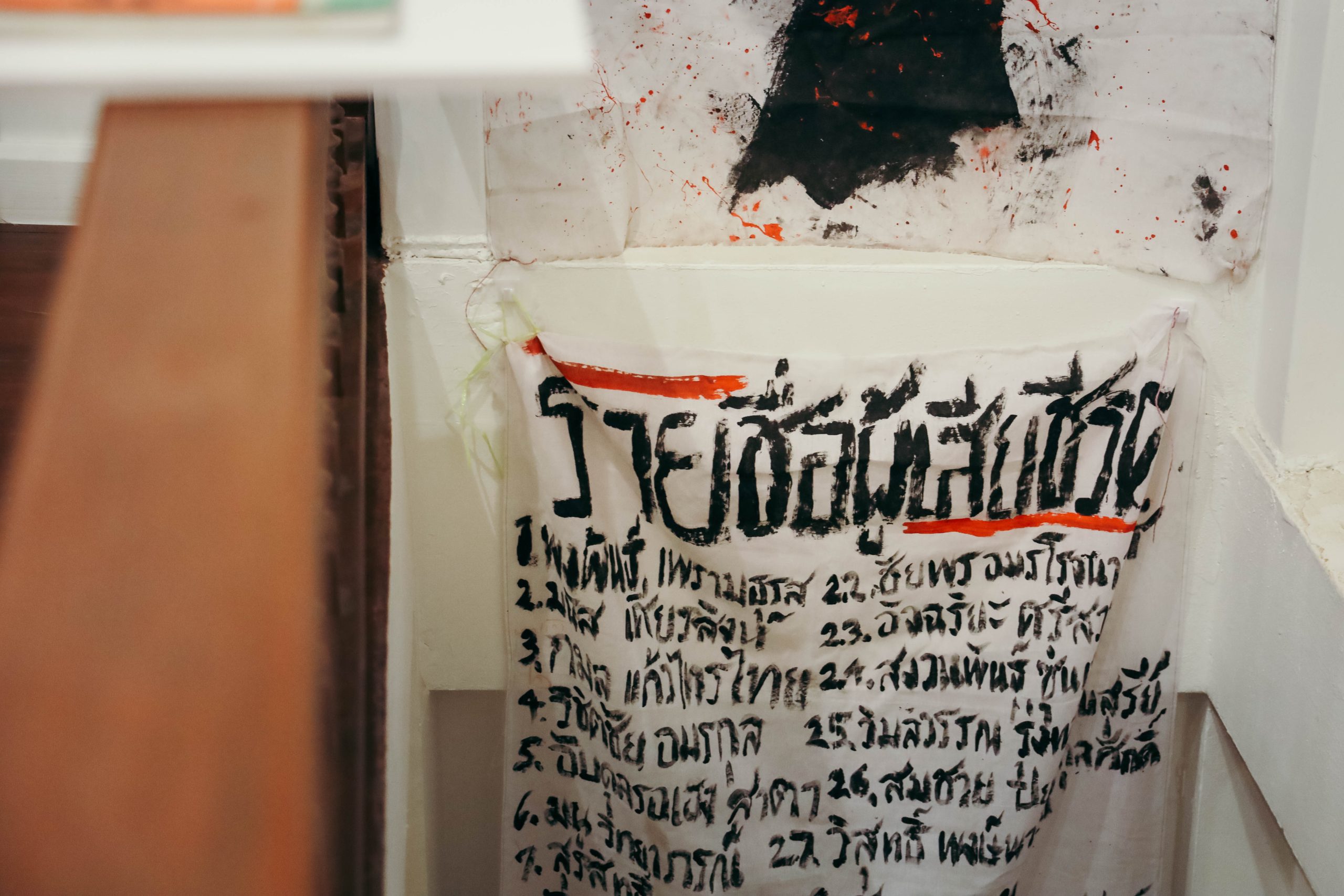

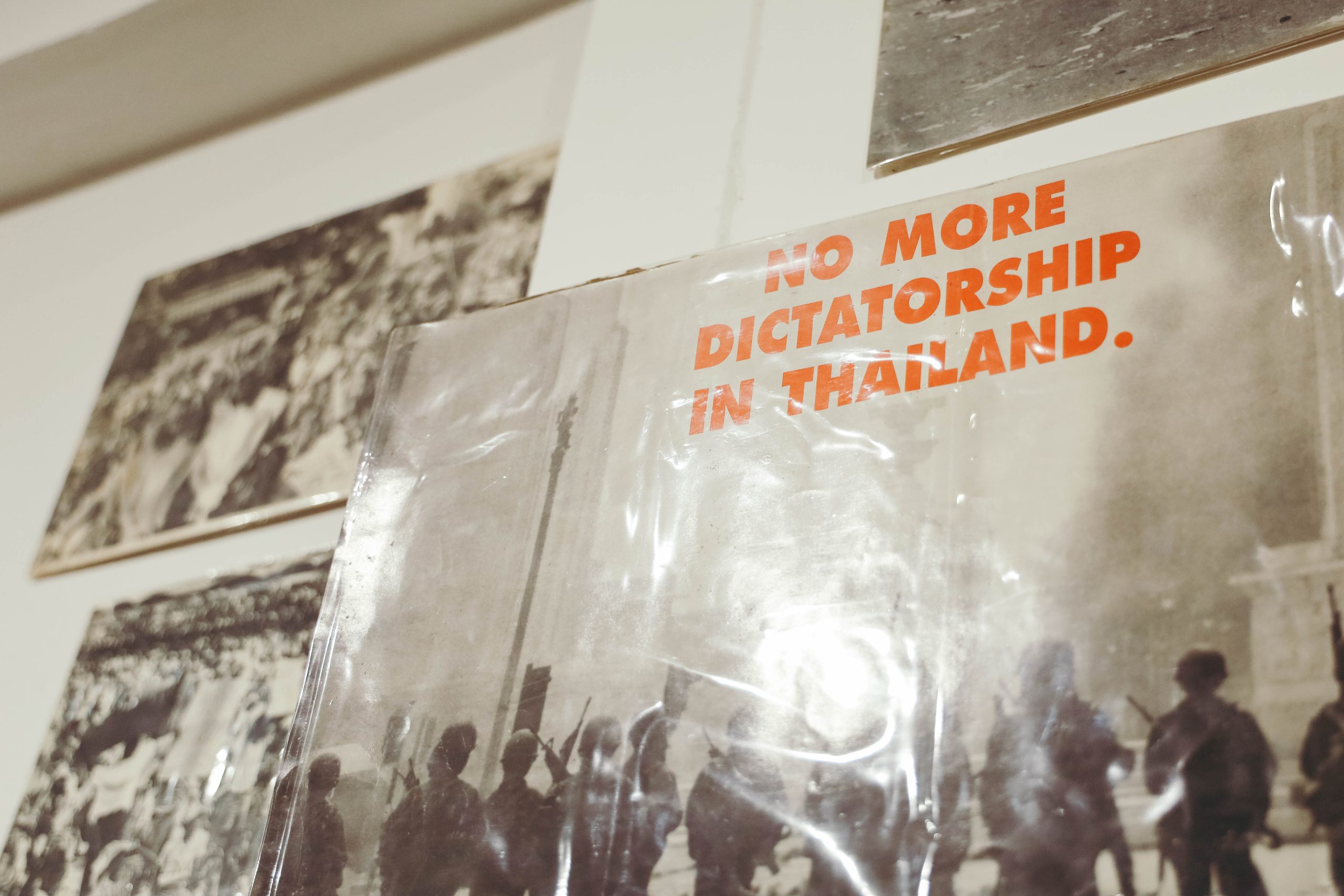

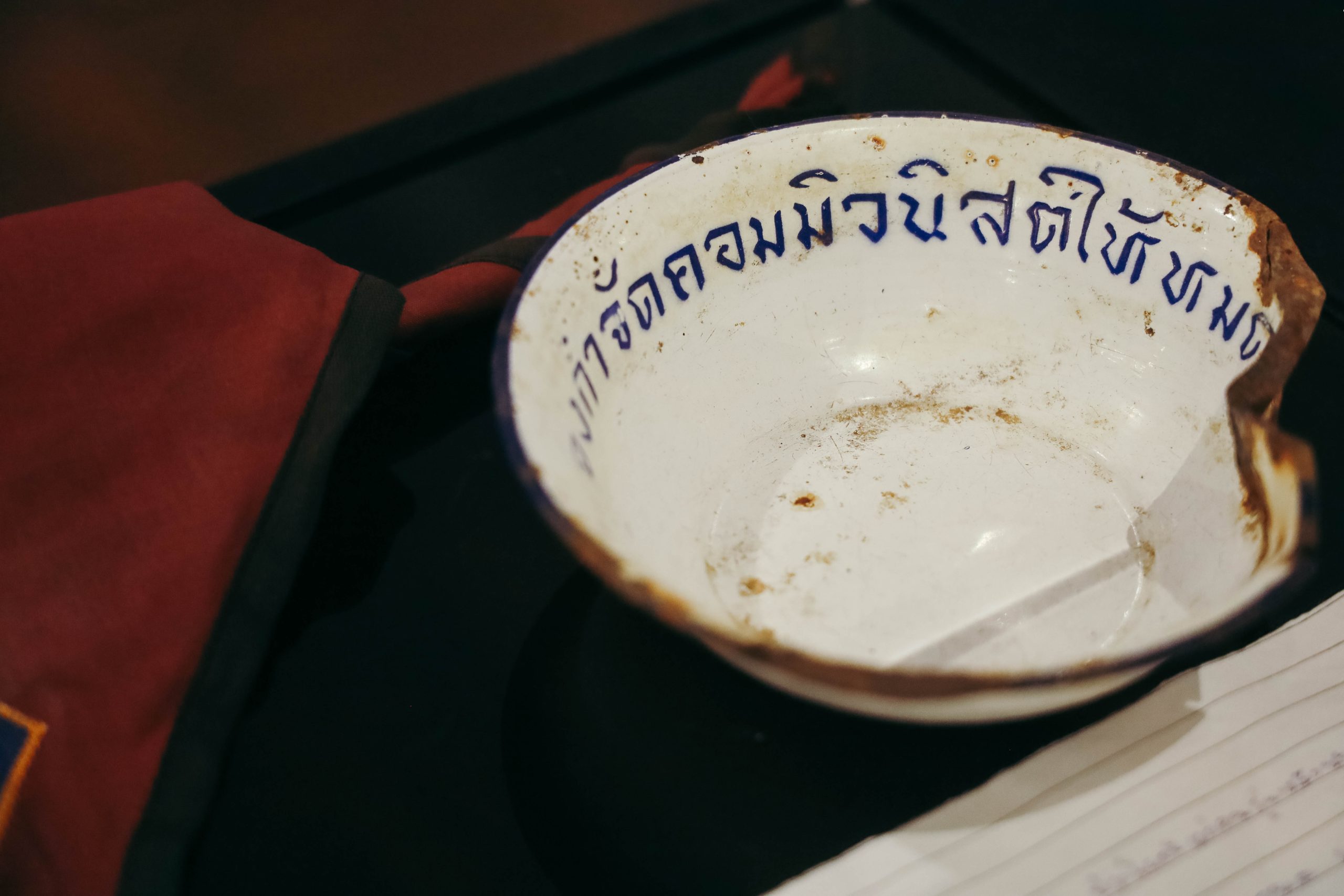

AC: Because objects and artifacts are a part of a movement. They were filled with people’s emotions and sentiments. For example, the sign that has ‘If we had good politics, my mom would have a washing machine’ written on it or something along that line, what this sign does is it documents the mindset of people in this particular time period that they don’t look at politics as something that’s irrelevant to their lives. They don’t agree with the belief that politics is an adult matter and that they have to wait until they’re grown-ups to be politically active or express their political views. It isn’t like that at all. If the political situation is bad, their quality of life will never improve. This is what the people in power have been trying to deny. They’ll say, you’re a kid, you should focus on your studies. Study hard and you’ll have a good life. But the reality is you studied hard, you even got a student loan but you end up working a job that pays you 15,000 baht a month.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

People in these movements tend to look at these objects as what they are, for example, to them, a sign is just a sign. But imagine the day when the issue they are advocating becomes successful, these signs will become a part of history and if we don’t keep it, it will disappear.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

Or if you think about old newspapers, the issues that were published during the 2010 protests, when they were released, we didn’t give them any value. You might use them to wipe a window or something but right now, those newspapers are incredibly valuable. You can’t get them anymore.

art4d: How long have you been collecting these items?

AC: I have been collecting for a long time but I started collecting seriously in 2018 after the We Walk march in Khon Kaen. I saw this white canvas that they prepared as a part of the activity. So people would dip their feet in colors and walked on the canvas. I saw that and I thought to myself that I wanted to keep it. I didn’t say anything at the time. I thought I’d ask them later. But that never happened because nobody knew where that canvas was. Activists are all about moving toward the future but I recognize the importance of collecting. That’s when I started to collect things seriously. My skin is thick now. If I see something interesting, I’ll ask right away.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

art4d: Where did you get these items most of the time?

AC: I bought some of the items like t-shirts but some of the old t-shirts were given to me. I have had people contacting me through the Museum’s Facebook page and telling me “I have these things, do you want them?” If I told them that ‘yes I’m interested,’ they would mail them to me. But I usually buy most of the items. I do get funding from international institutes to buy these items. I did an internship with International Institute of Social History, an organization from the Netherlands and they, too, were collecting items from different movements and protests in Thailand so I helped them with that. I created an archive for the items and recorded the shipping details.

art4d: What are your criteria in terms of what you collect?

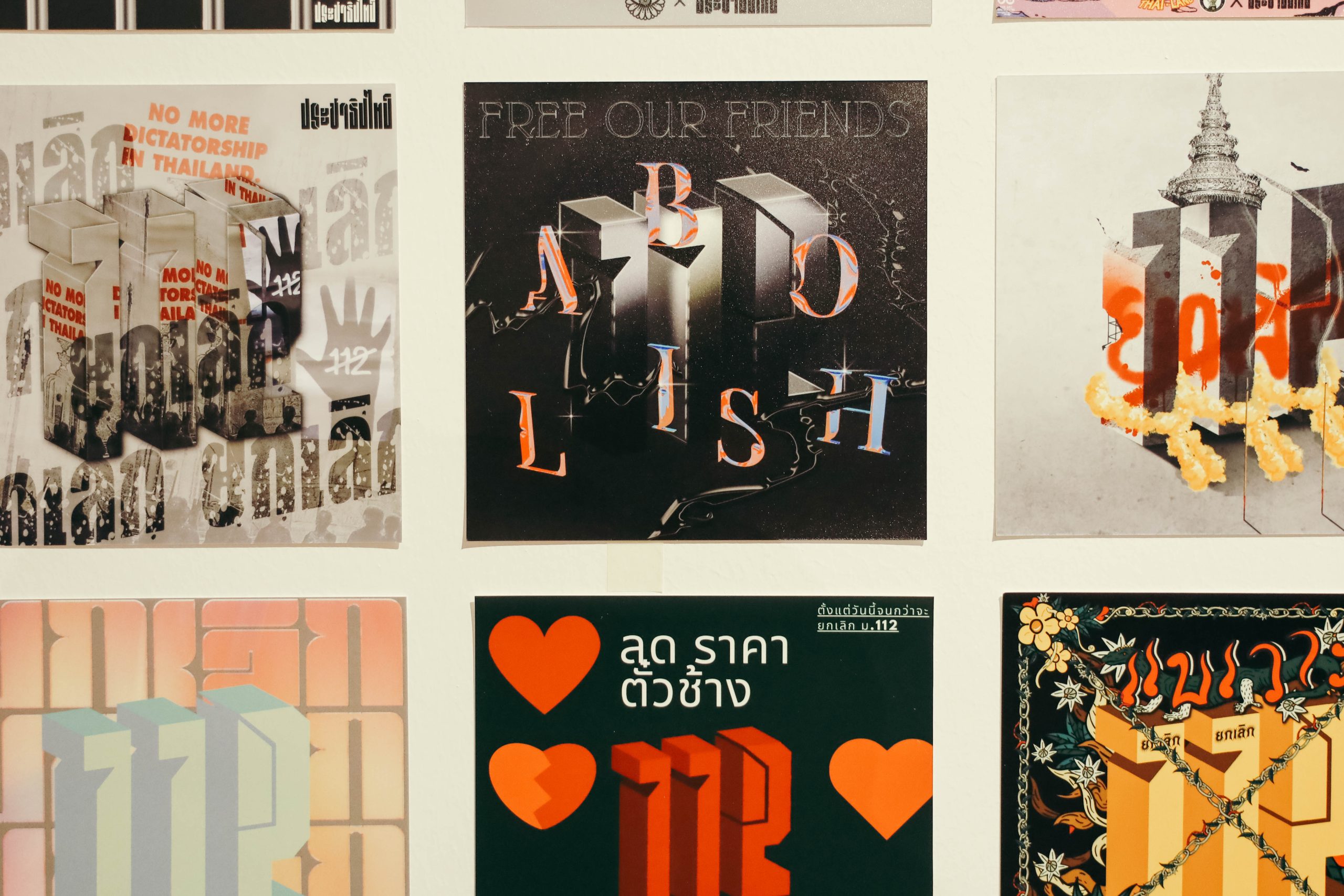

AC: I look at how an item is related to a significant historical event. Sometimes it’s my own judgment whether I find this particular item cool or interesting. But I try to collect items from every political movement no matter what side they represent. You can’t know the full story of the red shirt movement if you don’t know the history of the PDRC. These movements, whether you love or hate them, impact each other. They wouldn’t exist without the other. You cannot talk about one group of people’s story without the story of its counter movement.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

art4d: What were the obstacles that you have had to deal with so far?

AC: This isn’t my full time job. I do this in my free time, when I’m not working so it’s hard to manage. This project only involves myself and the other person assisting me but we have to do a lot of things. We have to photograph the items, archive them, put the information on the website and Facebook page, and then we have to contact and communicate with a lot of people. But it proves that every job, every position is valuable. Big organizations may not acknowledge the importance of administrative officers or messengers but everything is interconnected so if someone is missing, the impact has chain reactions.

Take the Museum of Popular History exhibition at Kinjai Contemporary for example; if we didn’t have the gallery team helping us, we’d be doomed because there were limitations regarding the budget, personnel and so on. But the gallery team helped us tremendously with the exhibition as well as the activities we organized as a part of the event.

art4d: Now that you mentioned the exhibition, would you mind telling us a bit more about it, how did it come about?

AC: The exhibition is like this imagination we have for the museum, what it would look like, the appearance, the character, in the flesh, in the real world. We were racking our brains with the gallery team about the theme. The initial date for the exhibition was actually supposed to be earlier this year and we came up with this super grand name, ‘New Year Revolution’, which was actually inspired by a wrestling event (laugh). We wanted to convey the exhibition as this event that would gather the significant political phenomena that occurred in Thailand. But the gallery team said that the items speak about a lot of issues so we really didn’t need a theme. They mentioned how we could just tell the story of the museum, if it were to have its own physical space and building.

The exhibition space is divided into different zones, following different political incidents that took place. The room on the second floor exhibits only t-shirts, with each corner displaying a number of incidents. But if you look closely, you can see that the incidents are actually connected. The October 6th incident and Sergeant New is fundamentally the same thing. They’re both about violence and brutality. We saw that picture where that man was hung at Sanam Luang and on the other side of the room, you see the bloody t-shirt that belonged to sergeant New. That’s how parts of history are connected. These items are telling us that we are in this cycle. When you finished looking at the exhibition, you would think to yourself, shouldn’t we have escaped this vicious cycle by now?

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

art4d: What’s special about this exhibition?

AC: This is the biggest exhibition I have ever done. We used to organize small exhibitions here and there and had galleries borrowing our items for their exhibitions.

The contents of this exhibition will always be up to date, because new items will be added continuously. Sometimes I would come across something new or people would send me things. That means that this collection isn’t a complete history, and it’s still very much alive.

It’s kind of depressing in a way. Why? Because it’s the kind of thing that we wish was already in the past. We are still debating about equality, how to vote, about putting people in jail. We have been debating for far too long. If this exhibition is still contemporaneous, it means that we’re still trapped in this damn cycle. I feel like I want this to be the past already so that today we can finally talk about something else and look back at these things and incidents as these horrible lessons that had happened and will never be repeated again.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

art4d: What’s the significance of organizing an online exhibition when people can look things up on the Internet?

AC: My thought is that by being able to see the real thing, the learning experience will be much more effective and compelling. Scrolling through the screen and seeing the real thing is totally different. It’s like seeing the real Mona Lisa at the Louvre is nothing like the image you see on the screen of your smartphone because the real thing is right before your eyes, so the experience is never going to be the same.

Viewers can touch some of the items in this exhibition, and there are certain items where I have to put up the ‘Do not touch’ sign. Tactility is a more fulfilling experience for sure compared to when you’re allowed to only look at something. But there are items that are really fragile and delicate so I have to cover them up, like books that can just easily fall apart from just a simple touch.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary

art4d: Have you ever dreamed of how you want the Museum of Popular History to be in the future?

AC: Dream? I’ve dreamed of having a small gallery, similar to Kinjai, which is the venue of the exhibition. I want it to be a space for a permanent exhibition, and it can host other exhibitions under different themes. I want it to have a space that can put together activities for everyone to participate. But it won’t happen within these five or ten years because I don’t have the money or the resources at the moment.

Museums are rich people’s business. It’s either that or it’s government funded. And even if you have the government support, they do expect something in return and it doesn’t have to be money or profit. For the state, museums function like a socialization tool. But the problem about my museum is that the state may see no good in supporting us because they gain nothing from it. But I think in the end, the state mustn’t forget that its citizens aren’t just living their own lives. They are a part of the force that will move this country forward and make this country a great country. If you say our country is already great, but that greatness comes from all the working ants who perform their roles and do their jobs. That, you can never forget.

Photo courtesy of Kinjai Contemporary