THIS TIME OF VIEWS BY KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE AND JENCHIEH HUNG LOOKS TOWARD PUBLIC UTILITY BUILDING PROJECTS FROM NODE ARCHITECTURE & URBANISM WHICH RAISES AN IMPORTANT QUESTION ‘HOW CAN ARCHITECTURE MOBILIZE A CITY?’

TEXT: KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE AND JENCHIEH HUNG

PHOTO: NODE ARCHITECTURE & URBANISM EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

In the past recent years, those who have been following news and updates from China would probably be familiar with ‘One Belt One Road.’ This global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government aims to connect China to other members of the global community, particularly countries in Asia, the Middle East and Europe, through a massive network of land and water transportation infrastructures. The new route will be reminiscent of Silk Road, the historic route established by the Han Dynasty 200 years B.C. This developmental plan has not only brought about a wave of awareness and enthusiasm in national and provincial policy making, but towns and cities have also begun to adjust their policies to be in conjunction with the new initiative. While China’s infrastructure development has been ongoing for well over 30 years, with urban developmental strategies initiated in the country’s major leading cities that have important national economic, political and social impact; Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Tianjin; the process is now expanding to other less prominent cities nationwide as preparation for future urban expansion.

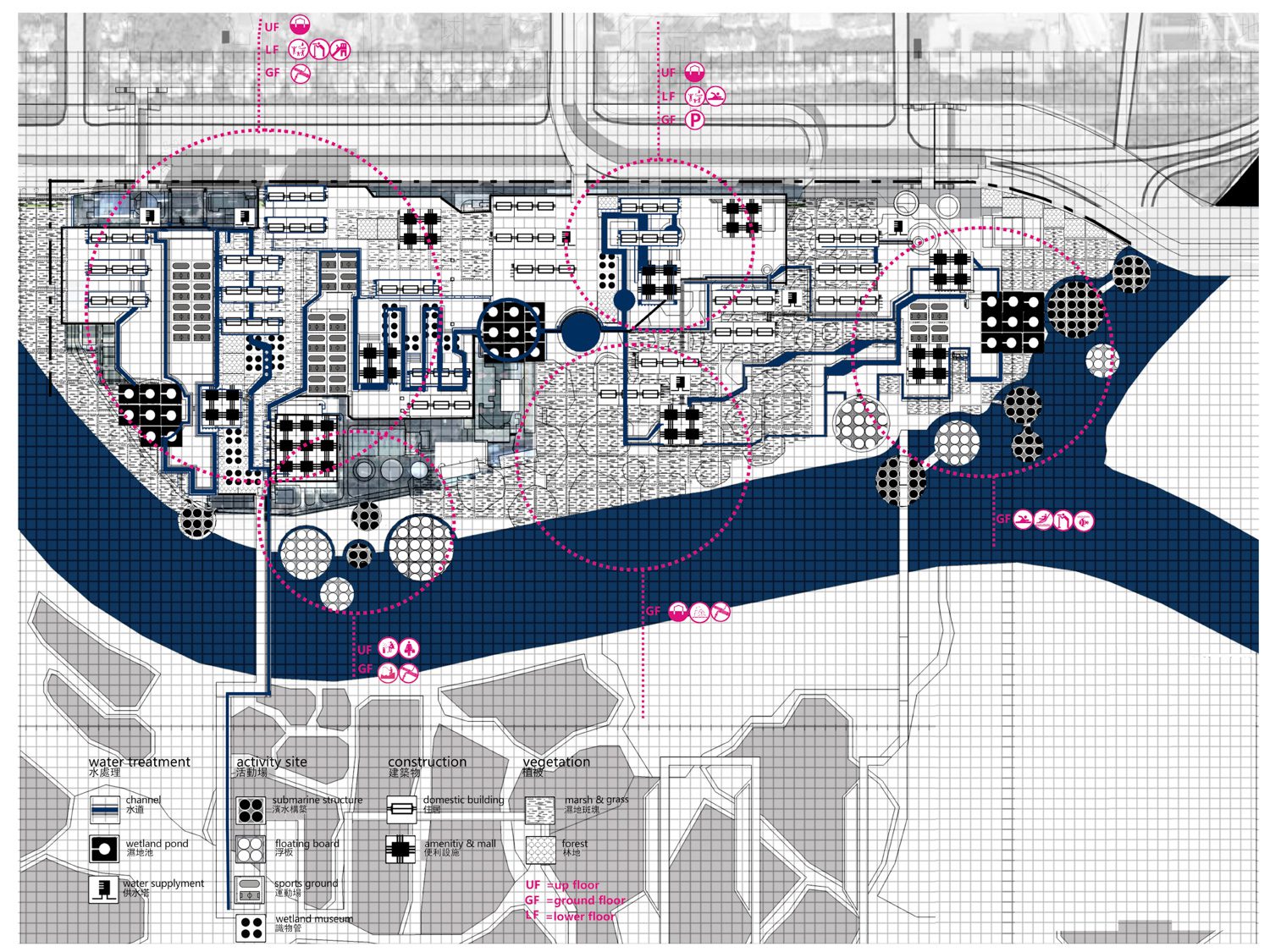

The master plan of one of NODE’s research on initiating a new water cycle in Shenzhen. The new cycle relies less on water sources and water distribution network, but more on water treatment and recycled waste through the reformed circular system designed to create a new and more sustainable way of life on a local scale, which eventually led to the birth of the idea of common infrastructure of the Inter-Infrastructure: Water Urbanis project l Photo courtesy of NODE

Nansha, the fastest growing port in Southern China in a suburban district of Guangzhou is one of the five major cities of the country’s southern region, and serves as one of the examples of development that started from zero. Nansha has evolved to its current status as one of the most prominent ports with significant influences on the country’s economic progresses as well as its reputation as a famous local travelling destination. In 1994, Doreen Heng Liu, a Guangzhou-born architect, graduated with a master’s degree from UC Berkeley, the United States, and decided to return to her hometown following an invitation from a Hong Kong real estate developer who asked her to help develop a 22 square kilometer land into Nansha’s new business district. Doreen, who had just started her practice as a professional architect for only a few years, was blown away by the request to design and construction of several major buildings in the city she was asked to be a part of, among them were Nansha Science Museum and Guangzhou Nansha World Trade Center Tower. However, throughout almost the entire decade of working, Doreen came to realize that the architectural creations she designed were creating a new city with no spirit of an actual city. The spaces surrounding those built structures were not contextually related to the urban characteristics of Nansha. In 2004, Doreen opened her own practice, Node Architecture & Urbanism. The word NODE originated from Nansha Original Design or NO Design in Nansha and Hong Kong with an important question of ‘how can architecture propel a city’s urban context?’ She went back to the United States to pursue answers to this question at Harvard Graduate School of Design and received her Ph.D. in design before coming back to China and relocating her firm Shenzhen in 2009, where she continues her practice until today.

Doreen Heng Liu’s profile picture l Photo courtesy of NODE

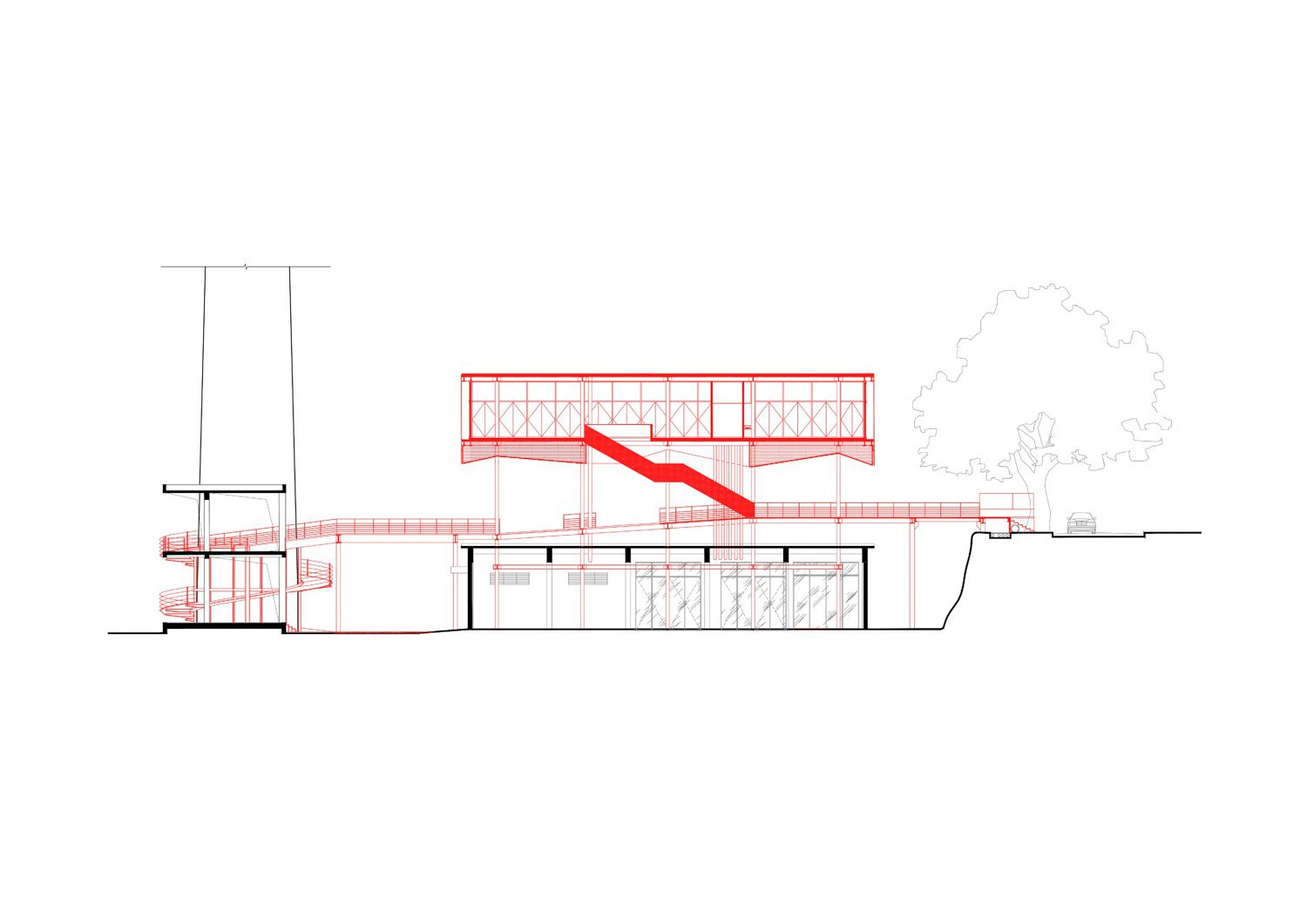

Doreen’s determination to find the possible answers and balance between architecture and cities has resulted in NODE’s body of work to bring a new wave of critical thinking toward buildings and infrastructures in China, which used to exist merely to serve and function as a part of the public utility systems, disconnecting themselves from people despite their existence as a part of cities’ urban contexts. Her work has transformed these structures and spaces into learning spaces, which have ended up bringing new and incredible values to the built structures, making them truly significant and meaningful components of the cities of which they are a part. One of the examples is Shenzhen Yong-chong River Sluice, an urban infrastructure whose existence had never been associated with aesthetics and beauty before. Most people perceive this type of structure as unattractive and boring, even though their significance and contribution to the city’s public utility system are acknowledged. The challenge of the design lies in the conditions, which require the design to turn the river sluice into something that can bring memorable experiences to its visitors, as well as a lively spirit to the city. The design was developed under the condition that the sluice must maintain the balance of the Yang-chong River’s water level. Meanwhile, the built structure has to function as a bridge that connects the two sides of the river. Doreen worked with the engineering team to maximize the efficiency and performance of the sluice’s system using height to determine the functionalities of the bridge and the door. Not only that, elements of architectural design were devised to present the actual mechanism used to operate the sluice into an exhibition. The red steel walkway of the bridge follows the structure of the system work, allowing visitors to explore the zigzag route and experience how the mechanism is operated from the bridge’s level all the way to the upper part of the equipment. From the area where public access would normally be prohibited to a sluice that is now a travelling and recreational destination and observation point for the city’s locals and visitors, the design has managed to create an infrastructure that no longer isolates itself from the city.

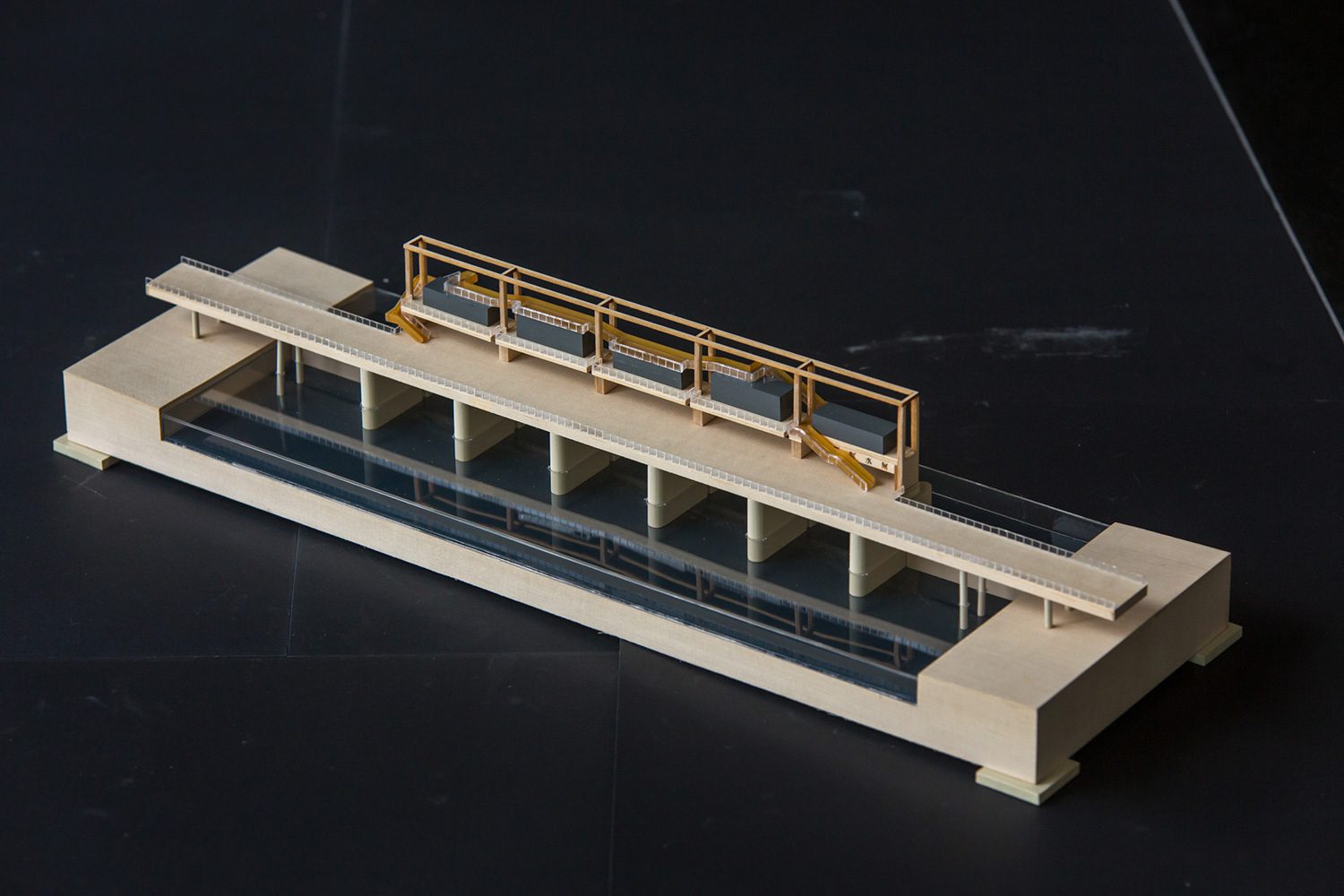

A model simulating the overview of Shenzhen Yong-chong River Sluice l Photo courtesy of NODE

The red steel walkway of the bridge follows the structure of the system work, allowing visitors to explore the zigzag route and experience how the mechanism is operated from the bridge’s level all the way to the upper part of the equipment l Photo courtesy of NODE

The red steel walkway of the bridge follows the structure of the system work, allowing visitors to explore the zigzag route and experience how the mechanism is operated from the bridge’s level all the way to the upper part of the equipment l Photo courtesy of NODE

China’s incredible economic advancement gave rise to the growing number of industrial plants in the country, consequently causing the water quality of rivers to deteriorate. The Pingshan Terrace: The Design of Pingshan River Water Purification Station – Public Infrastructure project located toward the northeast of Shenzhen is home to a water manufacturing station, which occupies the massive 100,000 square meter land. The project is one of the evident demonstrations of an aesthetically designed public utility infrastructure. When Doreen was assigned to oversee the design, the infrastructure of the underground clean water production had already completed its construction. The project’s owner, however, wished for the project to have a public space that would accommodate recreational activities of people in the area, corresponding with the urban planning policies that aim to elevate the significance of the area’s waterfront lands.

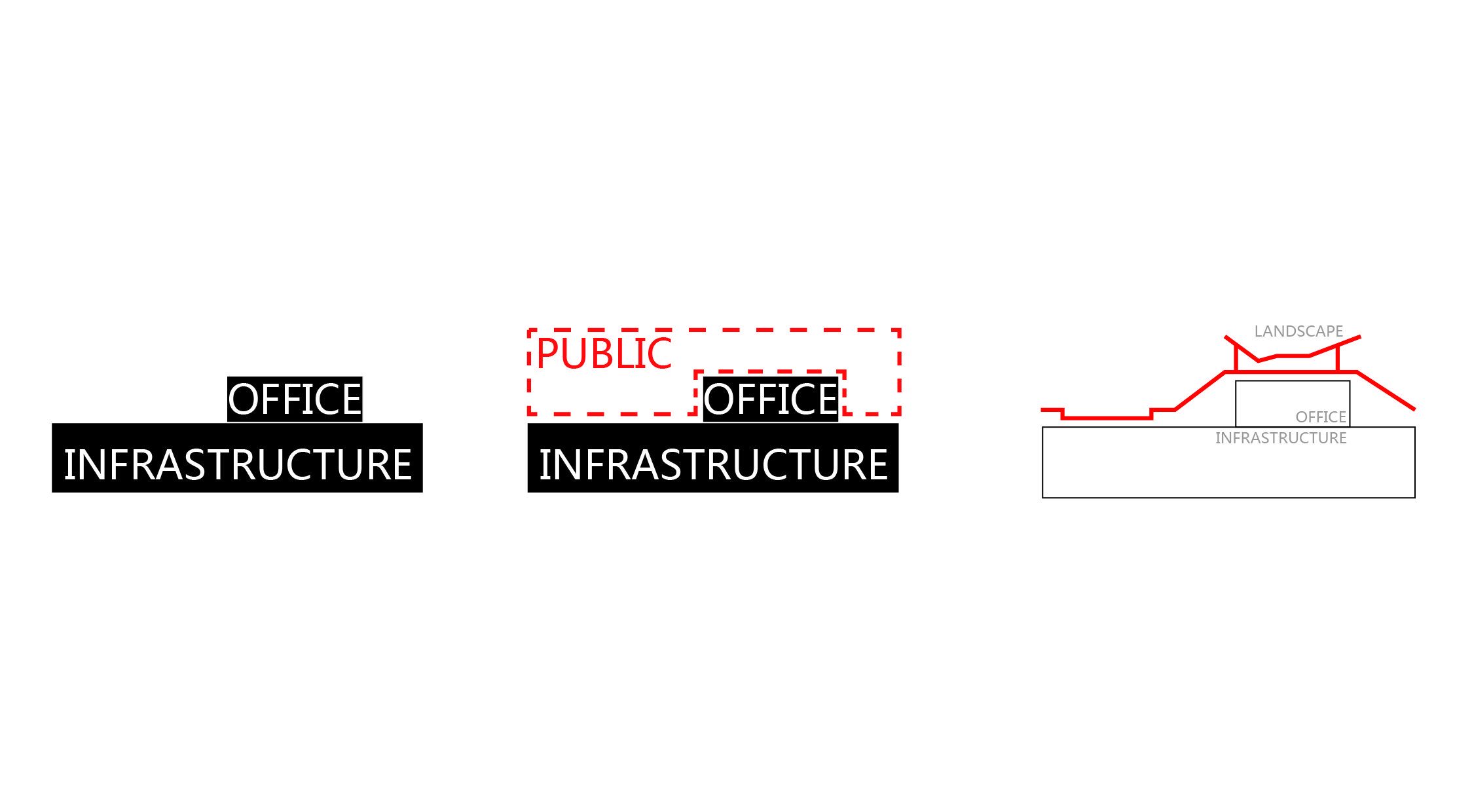

A diagram displaying the relationship between public spaces and public utility system’s functional spaces

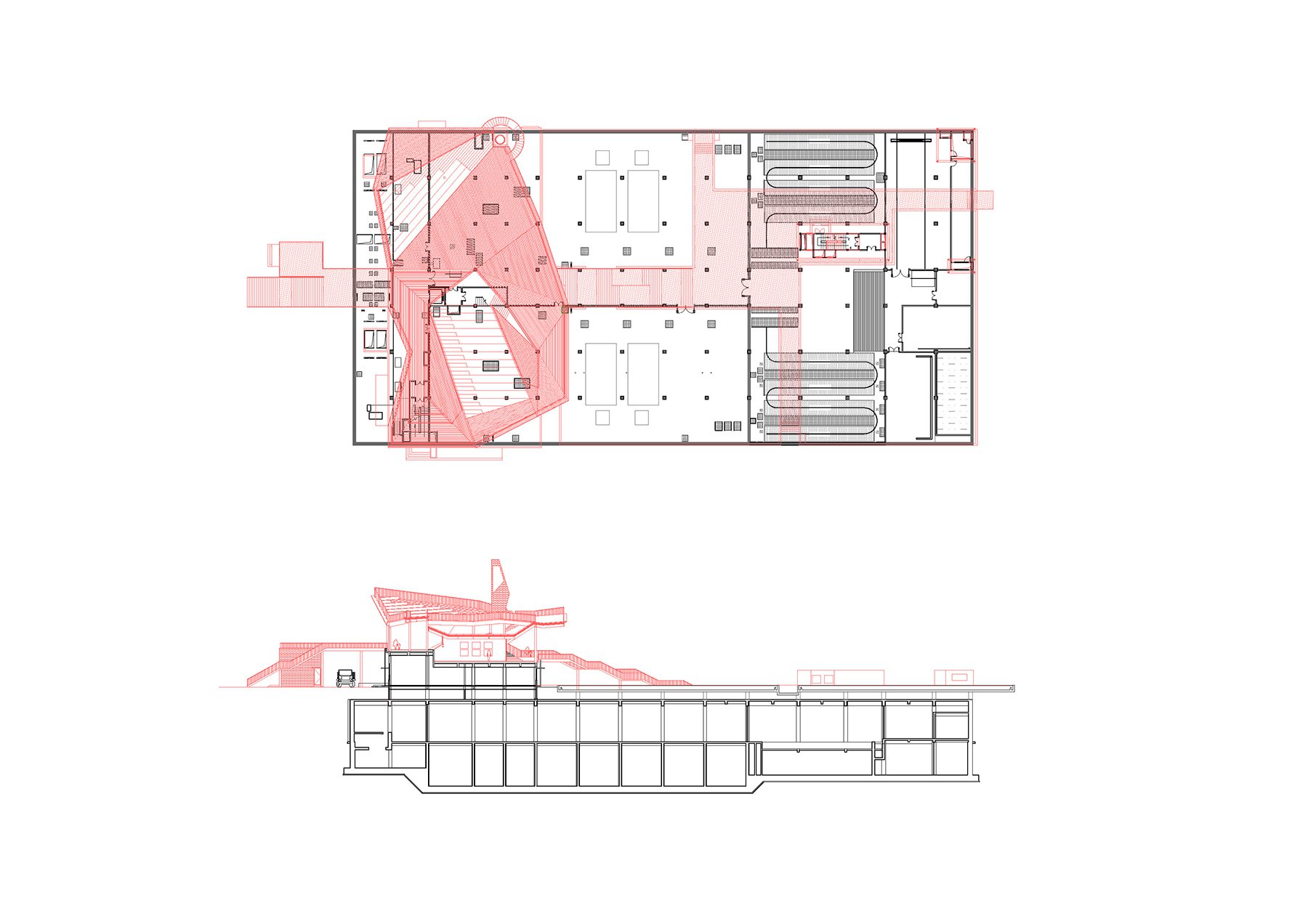

Floor plan and section displaying the public space with the red line, while the black line indicates the public utility system’s functional spaces

The design Doreen came up with for the project further develops the concept of the Shenzhen Yong-chong River Sluice, based on the same principle of ‘connecting nature to a city and bringing users and viewers new experiences.’ The building’s layout plan is straightforwardly expressed through the formulated axis of the public walkways connecting the north and south part. The walkway rests and leads visitors all the way up to the higher terrace, encompassing the roof of the office building on the second floor. In this particular area, viewers are able to see the entire process where waste water is treated before it gets released into Ping San River. The circulation leads visitors to gradually walk past the roof of the control room, and into the activity ground on the third floor. Another requirement of the engineering system of waste water treatment is the installation of multiple ventilation shafts to eliminate the smell. Each shaft needs to be at least 15 meters above ground level. Designing the system work that blends into the building’s architectural appearance means creating the kind of aesthetic that integrates architectural and engineering elements. The ventilation shafts are designed into something that looks like an artistic sculpture with spiral staircase crawling up and around the structure, offering an alternative to how the space can be explored and experienced. The connectivity between the vast three-dimensional plain, which connects the city to nature, ends up creating a new landscape for the river, and a recreational and learning space for the city. Meanwhile, the management of the public utility system underneath the plain maintains its efficiency and safety as it always has been.

The public walkways connecting the north and south part, resting and leading visitors all the way up to the higher terrace and encompassing the roof of the office building’s second floor l Photo: Zhang Chao

The activity ground designed to be a recreational and learning space for the visitors of the public utility system to experience l Photo: Zhang Chao

In addition to her role as a professional architect, Doreen is also a tenured professor and appointed distinguished professor at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning of Shenzhen University. She also taught at several world’s leading universities such as Chinese University of Hong Kong, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich and the University of California, Berkeley. Doreen has been selected to curate many editions of Urbanism and Architecture Bi-City Biennale; UABB hosted by Hong Kong and Shenzhen. With her design approach that highlights the revival of urban spaces, infrastructures and public spaces, Doreen’s architectural trajectory can be seen through a great number of projects she has completed, some of which aren’t even infrastructure projects. One of them is The Floating Entrance and The Warehouse at one of the main venues of UABB. The work proposes an alternative intended to facilitate a connection between old and new structures within the context of the city, with people’s accumulated experiences and perceptions of public spaces being a complementary factor.

Photographs and sections of The Floating Entrance and The Warehouse showing the integrated elements of old and new structures l Photo courtesy of NODE

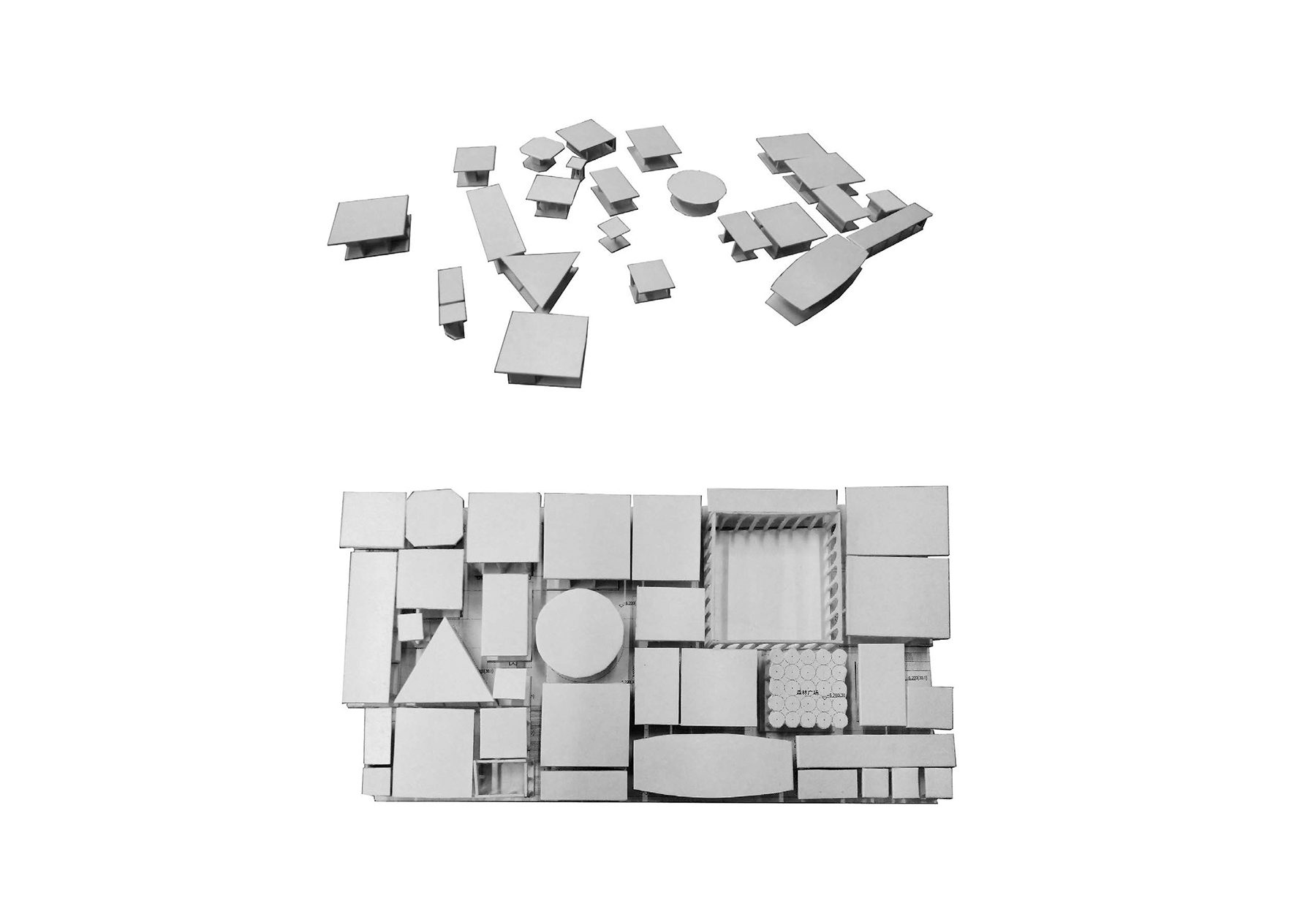

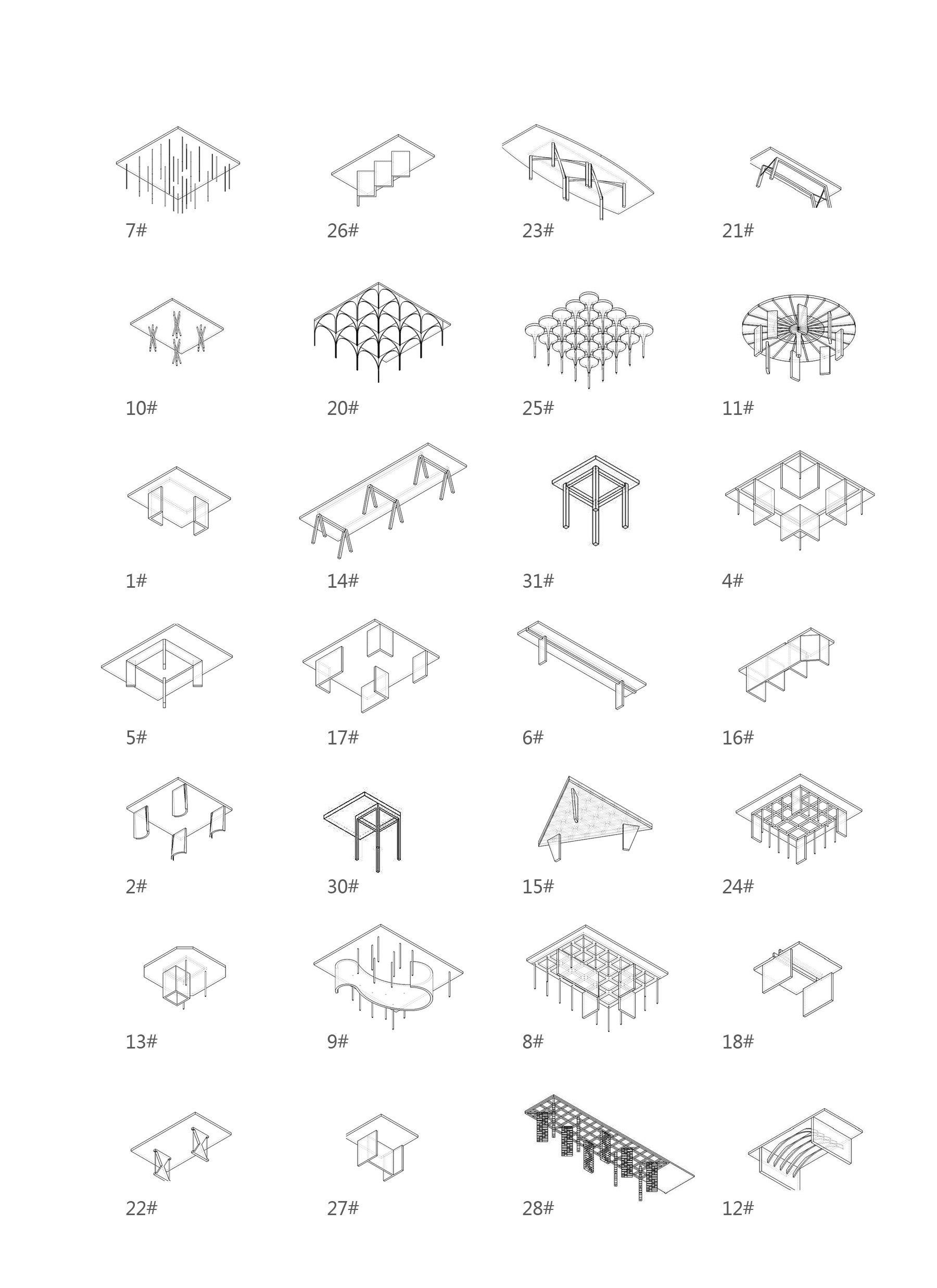

Table-Landscape: Plot B4 is a project where Doreen collaborated with one of China’s real-estate giant, Vanke, for an experimental development of an underground 7,000 square meter plot of land to create a creative office community with the project’s ground level preserved for a green public park. What’s difficult about the project is how the design needed to incorporate natural light and ventilation into the underground building. The design concept from the mind of an urban architect such as Doreen ended up dividing the entire space into 31 sections, each made of assembled frameworks of tables whose unified flat top becomes a home to a vast green space. Underneath the structure, each of the zones is varied by different functionalities while the spaces between the tables become the areas that welcome light and enhance ventilation.

The model displaying the layout of the Table-Landscape project, which is developed from the idea of putting tables together to create a smoothly connected surface despite the varying components of the structures underneath l Photo: NODE

A photograph of the building’s layout illustrating the green space at ground level, and the negative spac-es created as a result, causing the incorporation of natural light and ventilation of the underground level to be possible l Photo: Zhang Chao

A photograph showing the negative spaces created by an assembly of tables with different frameworks and structures, which ends up creating functional spaces with diverse spatial characteristics, including the effects of light and shadow cast on the surfaces of the underground floor l Photo: Zhang Chao

A diagram displaying the components of the 31 tables that are put together l Photo courtesy of NODE

Looking back at Nansha, the place that kicks off Doreen’s architectural expedition, from a practically empty city to what is it now with the government’s recognition in its importance, and pushing it to become a free trade zone that will serve as the economic gate for Guangdong province of southeast China. The city will help connect the Chinese waters to the global community, following the One Belt One Road initiative. When the development of infrastructure takes place at a provincial and then national level, ensuing are the promotion of cultural awareness and appreciation among the population with the aim to create citizens who are more culturally educated. The attempt is evident through the mushrooming of cultural buildings and projects since the year 2000 onward. Currently, China is home to over 5,000 buildings of this nature, as museums find their ways to small towns across the country. The development and opening of the country has caused architecture in China to evolve to the extreme, whether they are residential, office, retail, cultural projects or other types of buildings. Through this time period of dramatic advancement, infrastructural facilities were neglected and viewed as uninteresting works of architecture. Doreen’s works under the name NODE, in the past 18 years of its practice, have revived and reimagine pf these particular kind of structures into complete works of architecture that are more meaningful to cities and people. It would be very exciting to see this kind of thinking and approach become a trajectory and driving force being the design of infrastructure facilities in China and countries around the world. If that were the case, we would get to see these boring structures being transformed into something much more colorful and alive, bringing a wonderful spirit to a city, and fulfilling their role as a work of architecture, with integrity.