‘CURVES’ PLAY A PROMINENT PART IN OSCAR NIEMEYER’S BODY OF WORKS, INCLUDING THIS PROJECT WHICH IS HIS FINAL ONE. EXPLORE THE IDEA BEHIND THE DESIGN AND HIS IDEA OF THE CURVE WHICH IS ONE OF HIS MOST INFLUENTIAL IDEA IN THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE

TEXT: WICHIT HORYINGSAWAD

PHOTO: STÉPHANE ABOUDARAM / WE ARE CONTENT(S) EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

“I am not attracted to straight angles or to the straight line, hard and inflexible, created by man. I am attracted to free-flowing, sensual curves. The curves that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman. Curves make up the entire universe, the curved universe of Einstein.” – The Curves of Time

In the final years of his life, Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) often began several of his interviews with the above statement. It is actually an excerpt from the introduction of his autobiography, The Curves of Time (2000) written to document his memories on people, places and life stories of those he had come across, including his practice of architecture. It appears that ‘curves’ play a pivotal part in the architecture he had attempted and been able to create. For Niemeyer, architecture is conceived from each architect’s imagination and desire to create things that have never been done before. He rarely discussed architectural theories with anyone believing that with each architectural creation and the conceptualization behind it are an architect’s individual creative ability and aesthetic visions. To him, beauty holds more weight than function and other aspects of architecture.

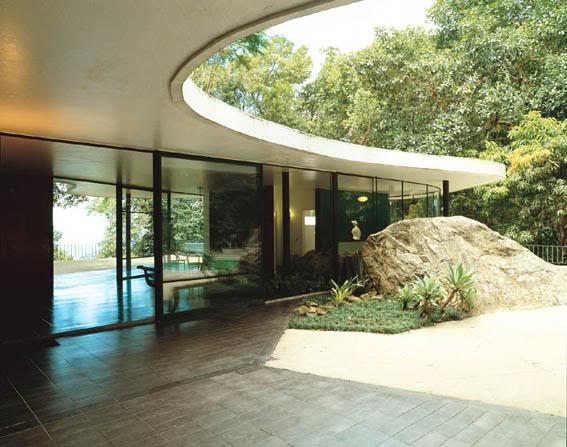

Casa das Canoas (1953) I Photo courtesy of Fundação Oscar Niemeyer

In 1953 Max Bill (1908-1994), another architect in the same generation as Niemeyer, wrote an essay piece after being invited to Brazil. The work documents the contents of his lecture at The University of São Paulo. Titled, Architect, Architecture and Society (1953), this particular piece of writing critiques works of modern architecture in Brazil and how they were more focused on physical forms and individuality rather than social issues or architecture’s role to contribute to the improvement of human welfare. Max Bill expressed his belief that such an issue is crucial to modern architecture of the western world, and that architects should work to serve this aspect of a society.

For Oscar Niemeyer, despite being on the left and supporting political movements of Brazil’s leftist political parties, architecture bears little to no association with politics (the belief sounds contradicting if we were to consider how the building of the ‘New Brazil’ image was largely attributed by the architectural development of the new capital, Brasilia (1960). To him, politics is about revolution, initiatives and movements that take place in the form of street protests.

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

In the booklet published as a part of Oscar Niemeyer: A Legend of Modernism (2003), Niemeyer wrote a short article titled, My Architecture (2003), where he divided the history of his own architectural body of works into five eras. ‘Pampulha’ is the first era where he deliberately went against sharp corners and boxy shapes, which were the products of Modern Architecture’s rationalization. He became interested in curves and the use of concrete to its fullest potential in the eras he referred to as ‘From Pampulha to Brasilia’ and ‘Brasilia.’ ‘Work Overseas’ and ‘Bew Building’ are defined as the time periods when he started to invest his interest in structural engineering techniques and technologies. Examining his works in all the eras, curves had always been a prominent commonality in his work and practice.

This year, the latest pavilion of Château La Coste, which is considered the last building Oscar Niemeyer has sketched (before his passing in 2012), finally completed its construction after over a 11 -year-long design and construction process. The building is a new pavilion sitting in the middle of a vineyard, surrounded by works of world-renowned architects from Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano, Tadao Ando, Kengo Kuma Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel, all the way to leading artists such as Chard Serra, Tom Shannon, Ai Weiwei, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Louise Bourgeois. The works were built and installed on different parts of the land where Château La Coste is sited.

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

The design process of the work began with Jair Velera, the architect who worked alongside Oscar Neimeyer for decades, travelling to Château La Coste in 2010 to choose the location of the pavilion. He returned and discussed with Oscar Neimeyer at their office and developed 4-5 editions of the sketches for Paddy Mckillen, the project’s founder to choose from. Velera visited Neimeyer at his studio on the Copacabana beach of Rio de Janeiro in 2011 where the now late architect explained the idea behind the building’s architectural form, which was inspired by the female form; a source of inspiration for several of his other works.

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

Niemeyer pavilion at Château La Coste l Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram / We Are Content(s)

The pavilion’s architectural characteristics consist of an enclosed cylindrical form whose interior houses an eighty-seat auditorium. The structure connects to a glass house building with a series of curved walls built with a number of columns constructed along the walls. The simplicity of the structure reminds us of Niemeyer’s early works from the Pampulha era such as Casa Do Baile (1943) and the architect’s own residence, Casa das Canoas (1953). The cylindrical form links to the curved part of the building with a row of columns visible behind the serpentine glass walls. Such an attribute resembles the round columns of the corridor of Casa do Baile, which cuts through the garden with a view of the lake and joins with the cafeteria. The building’s glass walls toward the north is designed into a curved form that clashes with the solid, enclosed shape of the white cylindrical building where the auditorium is housed. The protruding roof structure extends from the glass walls at the swimming pool, creating a separated rhythm between the walls and the curved mass of the roof – a wonderful throwback to what he did with Casa das Canoas.

Casa do Baile (1943) I Photo: Gabriel Fernandes

Casa das Canoas (1953) I Photo courtesy of Fundação Oscar Niemeyer

Casa das Canoas (1953) I Photo: Julian Weyer

Compared to Oscar Niemeyer’s past works, the pavilion may not be one of the most fascinating pieces from his architectural portfolio, especially if Château La Coste’s characteristic as a commercially driven cultural project were to be considered. Niemeyer’s long and consistent architectural career that was influenced if not rooted in his left-wing political belief had built a body of work that is full of museums, memorial structures, university and institution buildings. While it wasn’t that often to see him work on a project of this nature, the work can be deemed as a notable chapter in the history of architecture, not to mention how it’s the last work of one of the most prominent architects with a long-established and revered lifework.

Chateau la Coste - Provence - France

Chateau la Coste - Provence - France