KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE AND JENCHIEH HUNG FROM HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH INTRODUCE US TO A CHINESE ARCHITECT WHOSE WORKS EMPHASIZE THE REVITALIZATION OF THE URBAN AND RURAL AREAS BY SYNTHESIZING THE CITY’S PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT AND ITS SENSE OF PLACE WITH ARCHITECTURE

TEXT: KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE & JENCHIEH HUNG

PHOTO COURTESY OF ATELIER LIU YUYANG ARCHITECTS EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Since the 2000s, China has been a destination for architects and designers from around the world in search of new opportunities and creative possibilities. Architecture practices of various origins and nationalities have been placing their bets and opening their branches in major economic cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Chengdu. Chinese architects with higher education and work experiences abroad also come back home to start their own firms, many of which are new and widely reputable. Around this time, an architect with a distinctive background traveled to China in search of his own career prospects, just like others in the field had done. Liu Yuyang is a Taiwanese architect who holds a bachelor’s degree in urban design from the University of California, San Diego and a master’s degree in architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He was a member of Rem Koolhaas’ research team and co-wrote the 2001 book ‘Great Leap Forward’, which is regarded as a landmark study on the rapid expansion of the Pearl River Delta in China, home to cities such as Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Zhuhai. With his educational background in urbanism and architecture, and interest in both the academic and professional aspect of architectural design, he was invited to teach at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and later founded Atelier Liu Yuyang Architects (ALYA) in 2004. He subsequently moved to Shanghai and has since been living and working there.

Liu Yuyang (the second person from the right), one of the members of the architecture team behind the Huangpu River East Bund Riverfront Open Space Design master plan, along with Liu Yichun of Atelier Deshaus (the third person from the right) and Rem Koolhass I Photo courtesy of ALYA

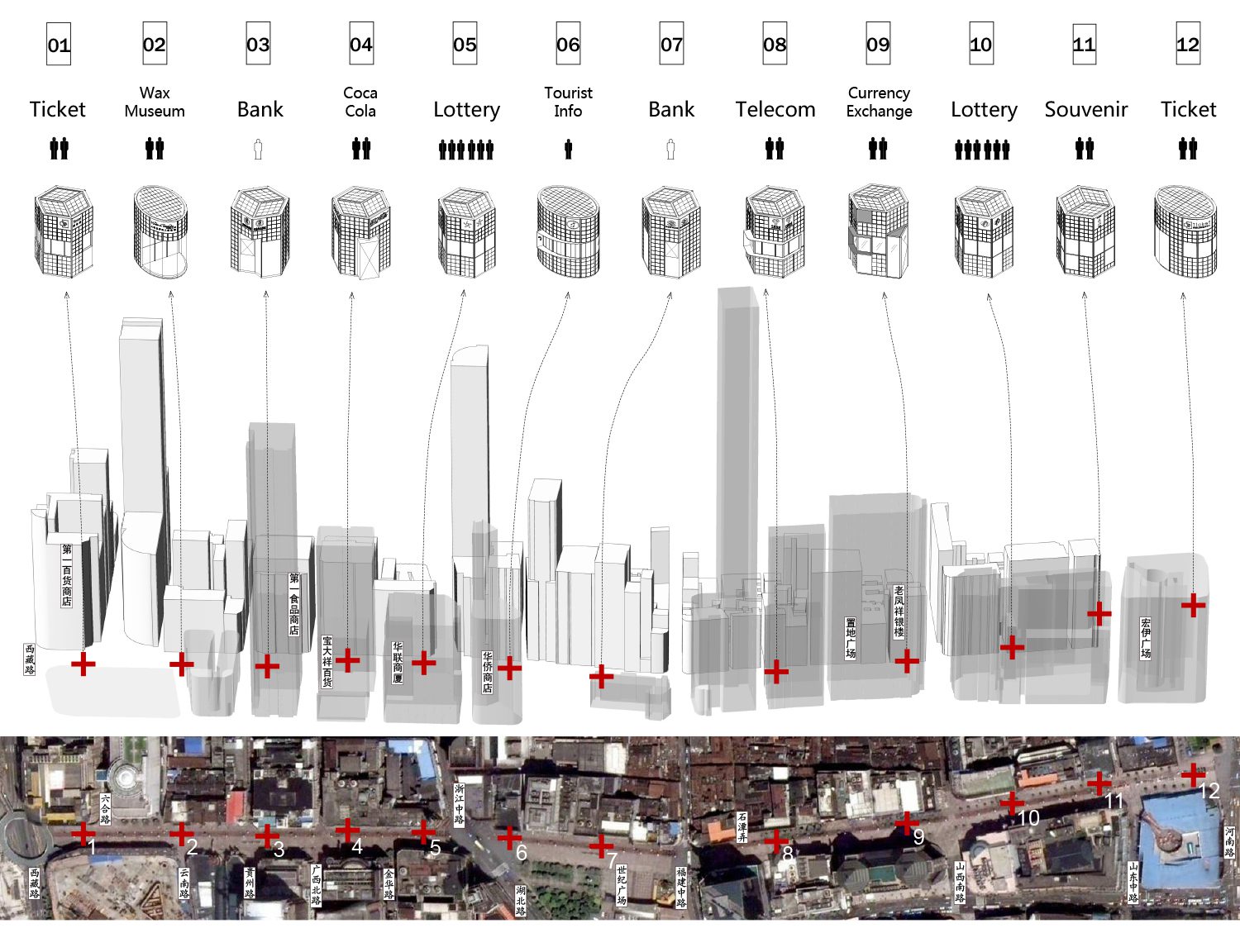

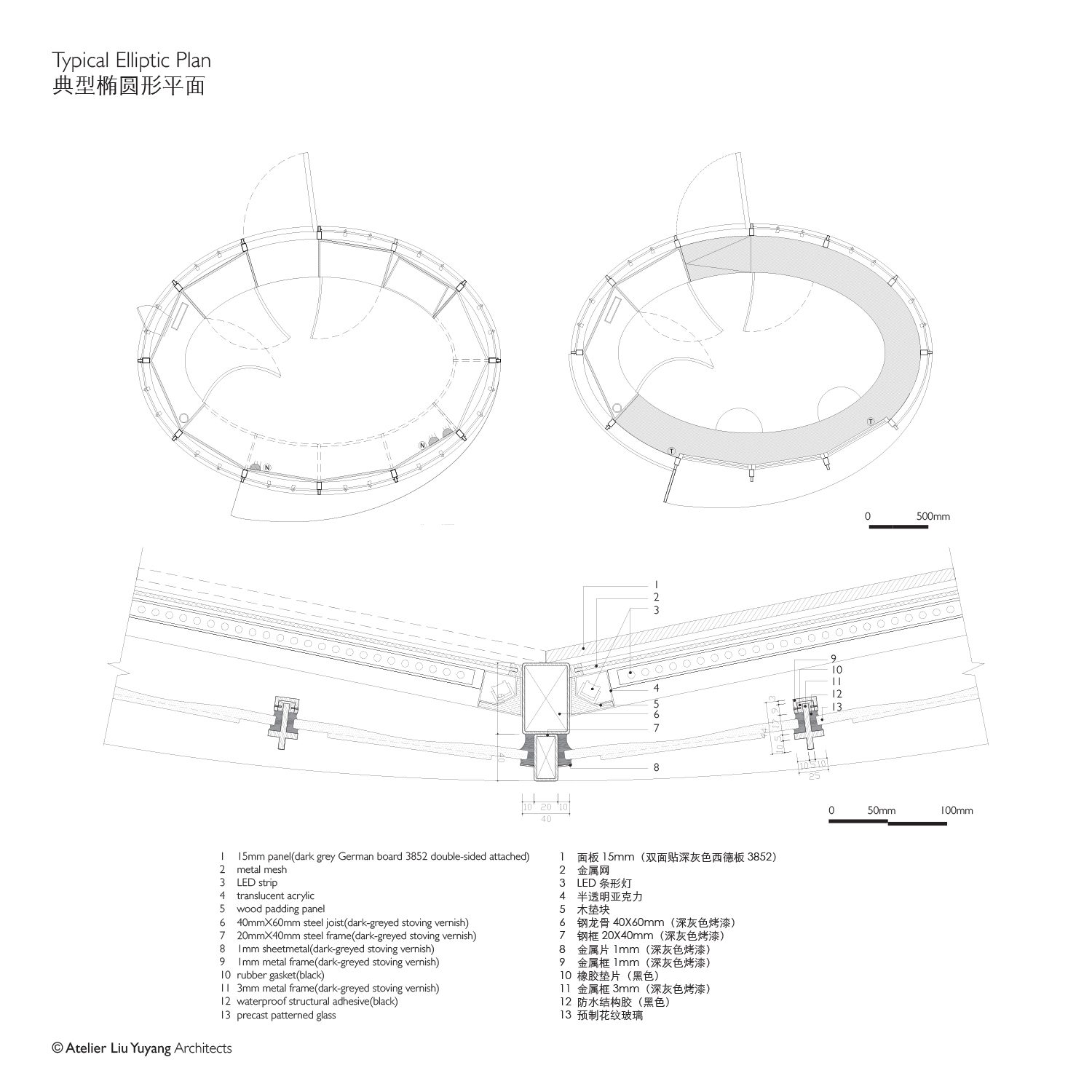

Multiple relocations have shaped Liu Yuyang’s viewpoints on the architectural profession and urban development. Through his practice, mindset and visions, he synthesizes his own architectural experimentation and the complexity of urban environments into works where every element exists within a sustainable dependency. Shanghai Nanjing Rd. Pedestrian Kiosks (2009), one of his earliest works, may be micro in scale, but it has resulted in a macro-scale of urban space reimagination. Twelve 4.5-square-meter tourist information kiosks were spaced 100 meters apart along the kilometer-long pedestrian street. Nanjing Road is one of the most visited historical sites and tourist attractions in Shanghai. Depending on the location, each kiosk is assigned with a certain purpose. Some function as a tourist information center, souvenir shop, lottery kiosk, while some house public telephone booths, ATM vestibules, and vending machines. Meanwhile, other kiosks have more commercial purposes and functions such as promoting places and products. The architect designed two different shapes for the twelve kiosks: octagonal and oval. The sizes vary according on the number of users, while the placement of the opening differs based on the location of each kiosk. Each kiosk is encased in a glass unit whose surface is adorned with a pattern depicting the splendor of Art Deco architecture built on both sides of the historical street. The solar cell panels installed on the kiosk’s roof generate the electricity necessary to illuminate the LED light, keeping the kiosk illuminated at night. After thirteen years, these kiosks serve not only as resting areas that reflect the evolution of the surrounding architecture, but also as a novel model of a distinctive urban landscape that does not burden the city with its energy usage.

The placement and program of the 12 kiosks along the 1-kilomter long Nanjing Pedestrian Road in Shanghai I Photo courtesy of ALYA

The two designs of the kiosk (oval and octagonal) encased in a glass unit whose surface is adorned with a pattern depicting the splendor of Art Deco architecture built on both sides of the historical street I Photo: Jeremy

Kiosk 6 Information I Photo: Zhonghai Shen

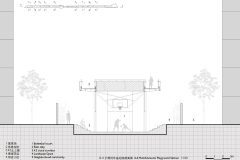

The floorplan and typical elliptic plan used for the installation of a oval kiosk

While new schemes and projects were being immensely devised and implemented in an endeavor to develop cities and urban spaces, 2011 was the year that the Chinese Government began to recognize the significance of rural development. It resulted in a shift in the country’s policy making with a greater emphasis on the revitalization of rural areas and promotion of diverse local ways of life in an effort to propose new ideas and concepts that could be developed into high cultures. The plan inevitably affected the Chinese design sector. The theme of the 2016 Venice Biennale, “Back to the Ignored Front,” was a research and compilation of the country’s long-standing traditions, exhibited alongside the question that called for serious speculation of the future of these neglected areas. It was also around this time that we began to see works of Chinese architects emerging in areas with rich natural surroundings. Some of the works were integrated to the context of locally built, old buildings. Designed by Liu Yuyang, Xingping Yunlu Resort (2015) and Yunlu Resort Yoga Pavilion & Pool (2018) are examples of the revival of rural environments. Chosen as the winner of the ARCASIA Award for Architecture’s Gold Medal in 2019, the eco, boutique resort is nestled in a town between Guilin and Yangshuo, surrounded by the picturesque landscape of the Li River.

A bird’s eye view image of the first phase of Xingping Yunlu Resort, which involves renovating five decrepit farmhouses and the newly-built restaurant and guest reception area I Photo: Shengliang Su

The restaurant and the overall surroundings I Photo: Shengliang Su

The physical model of the south elevation of the restaurant demonstrating the combined use of local and new material I Photo courtesy of ALYA

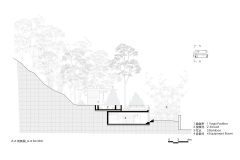

The project is divided into two phases. The first involves renovating five decrepit farmhouses and the newly-built restaurant and guest reception area. The second phase is the resort’s shared facility, which includes a yoga studio and a swimming pool. Designing a building that does not alienate itself from the local culture, including the nearby residential area and natural surroundings, landscape, and the maximum conservation of native plants, necessitates an inventive approach that combines the newness and the original characteristics of the existing built structures and environment. The yoga pavilion in phase two lies on the sloping terrain of the site while the native Sapindus plants that grew near the swimming pool are kept well protected. The 6×20 meter steel roof is supported by a robust, curved metal wall and A-shaped steel columns, while a translucent, UV-protection tarp is utilized instead of glass to create an ambiguous space where the inside and outside are indistinguishable.

A bird’s-eye view image of the phase two of Resort Yoga Pavilion & Pool, showing the communal facility with a yoga pavilion and a swimming pool I Photo: Fangfang Tian

Meanwhile, the revitalization of degraded and desolate rural regions was happening alongside these private projects. The Riverfront Aite Park project (2015), the Huangpu River East Bund Riverfront Open Space Design (2018), and the Caoyang Centennial Park (2020) designed by Liu Yuyang are three outstanding examples of how the urban renewal of cities can be achieved through design and how architectural elements work to synthesize a city’s physical environment. The Riverfront Aite Park was formerly a wasteland with piles of construction debris from the construction of buildings, which were included into the masterplan for the development of a 3.1-acre riverside landscape. The site is situated between a residential area and a factory zone in the Xiating district, a northern Shanghai suburb. Transportation costs were incurred to remove wastes from the site. The architect opted for a simpler, yet highly effective approach by utilizing Gabion Walls to store the construction debris. These 5-meter-tall walls create a unique feature for the park, while also serving as an interesting and concrete reminder to the community about the significance of environmental conservation.

The revamped landscape around the park’s entrance I Photo: Siyu Zhu

The sketches proposing ideas and methods of using Gabion Wall to manage the wastes

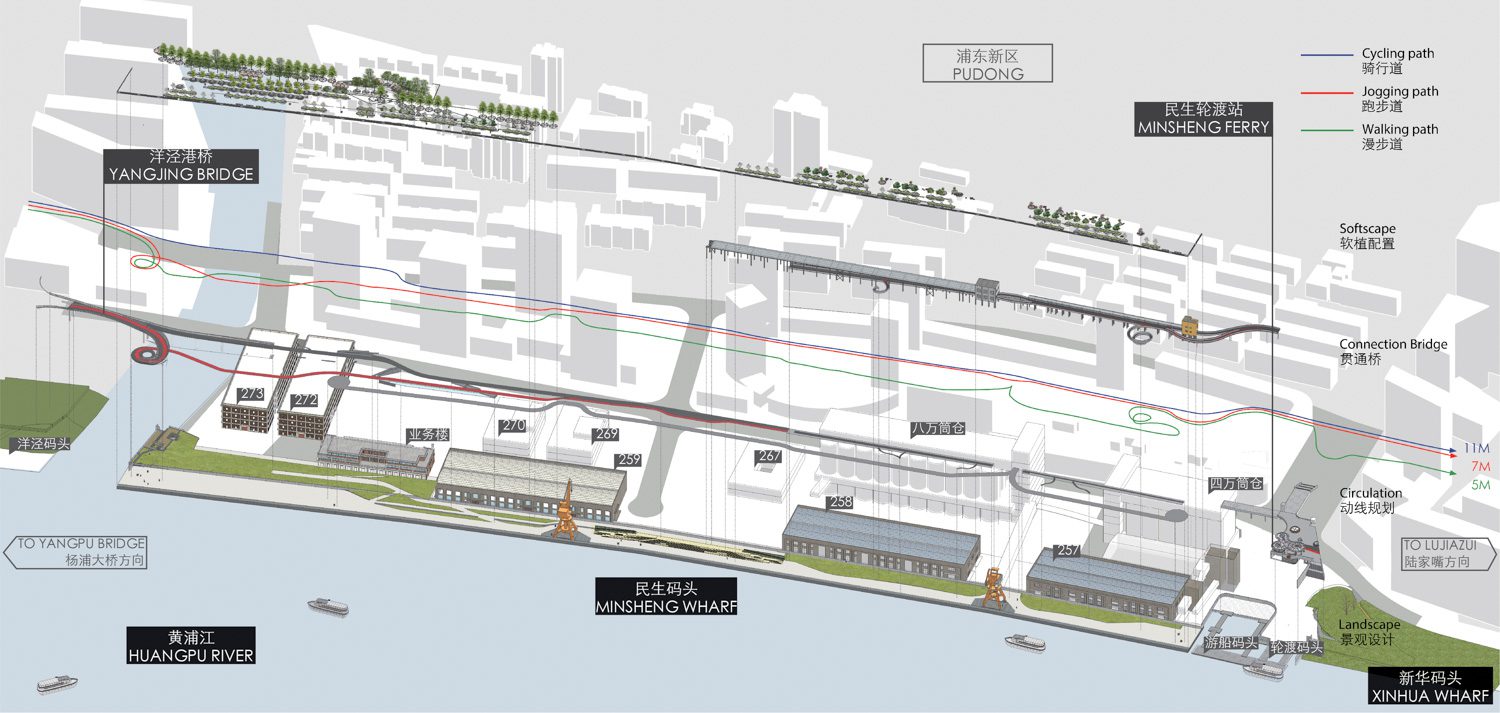

The Huangpu River East Bund Riverfront Open Space Design is the rehabilitation of the waterfront landscape by Huangpu River, one of Shanghai’s major rivers that divides the city’s western and eastern sections. The project is part of a plan to transform the industrial area to the east of the city, which was once occupied by enormous processing plants, into a vast public space for the city’s residents and visitors. Using the ‘coexistence between the modern and ancient landscapes’ approach, the development of the areas on both sides of the river resulted in the successful preservation of remains of the previous industrial spirit. The height of the flood defense walls hampered the design. The architect proceeded by examining different segments of the site, before carrying out detailed analysis to determine the heights and levels of green ramps, pathways, steps, and activity grounds. In the meantime, new spaces are being added to accommodate activities such as cycling, jogging, and walking, in accordance with the masterplan’s goal for the space to function as a hub of “art + daily life + activities,” which aims to contribute to a greater completion and continuity of the city’s urban fabric.

Aerial photograph of the redesigned landscape of the Huangpu River East Bund Riverfront project, illustrating the integration of new elements into the existing space I Photo: Fangfang Tian

Exploded axonometric depicting the re-connection of different activities and areas at various levels

The spatial relationship of the site designed to be a hub of ‘art + daily life + activities’ I Photo: Fangfang Tian

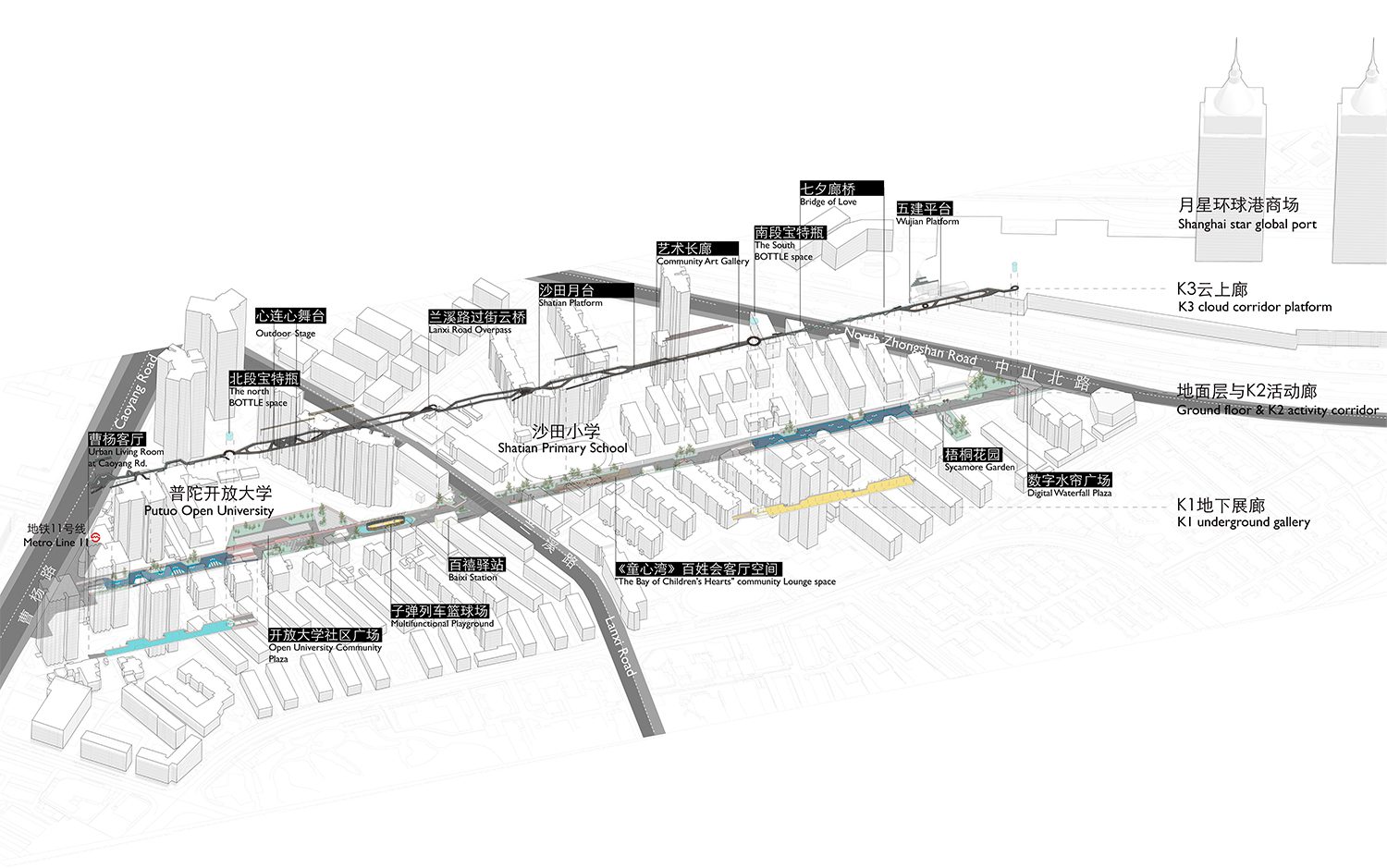

Another intriguing example of spatial development, typically observed in developing nations where infrastructures end up separating cities, becomes a new component in which cities are through design. Caoyang Centennial Park is located in Putuo district, to the northwest of Shanghai, in the one-kilometer-long, 10-15-meter-wide former railway site. In the preceding two decades, the area had been transformed into an outdoor market before it was closed in 2019 due to the pandemic. The district office intended to convert the land into a new public park that can be accessed on multiple ground levels, with a landscape that would connect the areas to the north and south of the park, allowing the park to become a community hub for the local neighborhood, which is home to residential areas, schools, and offices. The project was required to be finished in only one year due to scheduling constraints. Liu Yuyang proposed the concept of connecting the park’s neighboring areas via various spatial elevations. The park’s 10 zones include activity grounds, areas for recreational activities like exercise, playgrounds, and the green landscape. Steel structure was chosen due to its shorter building time. Bright vibrant colors were also chosen to add an intriguing element to the park by effectively defining levels and zones, thereby producing a new and revitalizing image that helps boost the spirit of the community.

The diagram depicting the interaction between Caoyang Centennial Park’s activities and spaces at different height levels and their surrounding context

An aerial view of Caoyang Centennial Park reveals how the design brings new activities to both sides of the road I Photo: Runzi Zhu

A photograph of the exhibition area where colors are used for the spaces at different height levels, and the fresh image and uplifting spirit the park brings to the surrounding community I Photo: Runzi Zhu

A photograph showing the relationship of spaces at different height levels I Photo: Runzi Zhu

Certainly, the revitalization of urban and rural areas in China will continue so long as design is able to improve the citizens’ quality of life and encourage the arrival and return of individuals with invigorating energy and spirits. The origin and success of Liu Yuyang’s synthesis of cities and architecture may be attributed to the forethoughts of local authorities and policy makers. As an architect and urban planner, Liu furthers his approach to urban and rural space regeneration by preserving the traces and spirit of places. His works illustrate a great compromise with local communities and the surrounding environments by integrating new, fresh images to contemporary activities and needs to create a more fulfilling future for the people. It will be fascinating to observe the regeneration of Chinese cities’ physical environments into a unified vision. How much this new image of ideal cities reflects the roots from which cities have evolved will depend heavily on the strategies and abilities of architects and urban planners to preserve the meaningful remnants and create cities of the future that still allow the younger generation to learn about their past, and how they have grown and evolved.