CHOMCHON FUSINPAIBOON TAKES US TO EXPLORE ‘THE ROBOT BUILDING’ WHICH IS AN IMPORTANT MILESTONE FOR THE ’THIRD WORLD’ ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN TO CHALLENGE THE GLOBAL ARCHITECTURAL MOVEMENT BEFORE THE BUILDING IS TRANSFORMED

TEXT: CHOMCHON FUSINPAIBOON

PHOTO CREDIT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

The renovation of the Robot Building on South Sathorn Road was announced in late March 2023. The building now houses the headquarters of UOB Bank (Thailand) and was previously the home base of Asia Bank. Due to the release of information about the renovation of the building’s exterior and section, several groups of individuals and experts have expressed their concerns through various social media platforms about how the restoration will end up changing the appearance of the Robot Building and potentially forfeiting its iconic design.

Experts in the fields have been calling out through the media, pleading for the public’s attention to the consequences of the Robot Building changing its physical appearance. The one agreeable thing in the discussion about the significance of the Robot Building is its value as a work of architecture. One of the debates that many people have yet to resolve is whether the Robot Building is a work of “postmodern architecture” 1 or “modern architecture”2 , based on the time of its conception and architectural style. According to an open letter published recently by the International Committee for Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites, and Neighborhoods of the Modern Movement, or docomomo Thai, the Robot Building is a historical landmark that demonstrates a transition from Late Modernism to Postmodernism3. This article invites all readers to join the conversation and attempts to illustrate how the story of the Robot Building is intertwined with the roles and status of Thai architects in the global context.

The Robot Building | Photo: Beer Singnoi

It is difficult to classify the Robot Building as “postmodern architecture” or “modern architecture.” The reason for such difficulty and what makes the building historically significant and encapsulates the ‘transitioning time’ are perhaps more interesting than trying to figure out what it is or what architectural style it falls under. The design and construction of the Robot Building took place between 1983 and 1986. The building, designed by Dr. Sumet Jumsai na Ayudhya, was originally intended to be Asia Bank’s headquarters (the bank was later acquired by UOB in 2005). If we examine the period in which the Robot Building was conceived, as well as the new architectural styles and innovations that emerged during the same time period, both inside and outside of Thailand, we can draw the conclusion that the building was conceived when modernism was criticized for being boring and lacking in identity due to its emphasis on utilitarianism as the universal standard. By specifically examining the architecture of the headquarters of other major Thai banks, it was discovered that the head offices of two major banks, Kasikorn Bank and Bangkok Bank, both opened in 1981, were both modernist skyscrapers. What distinguishes the two buildings is that each architect appeared to use a different concept and approach when it came to adapting western modernist architecture to Thailand’s hot and humid tropical climate. The first structure is a boxy, glass structure, whereas the second was designed with concrete canopies as the façade4. For Asian Bank, a smaller financial institution with a younger generation of bankers as executives, the design of the new headquarters had to reflect the new era of banking, with new technologies such as computers brought in to help improve its operations and services, all while representing the bank’s unique identity. So, the question then became about which architectural style would fit and should be applied to the design of the building.

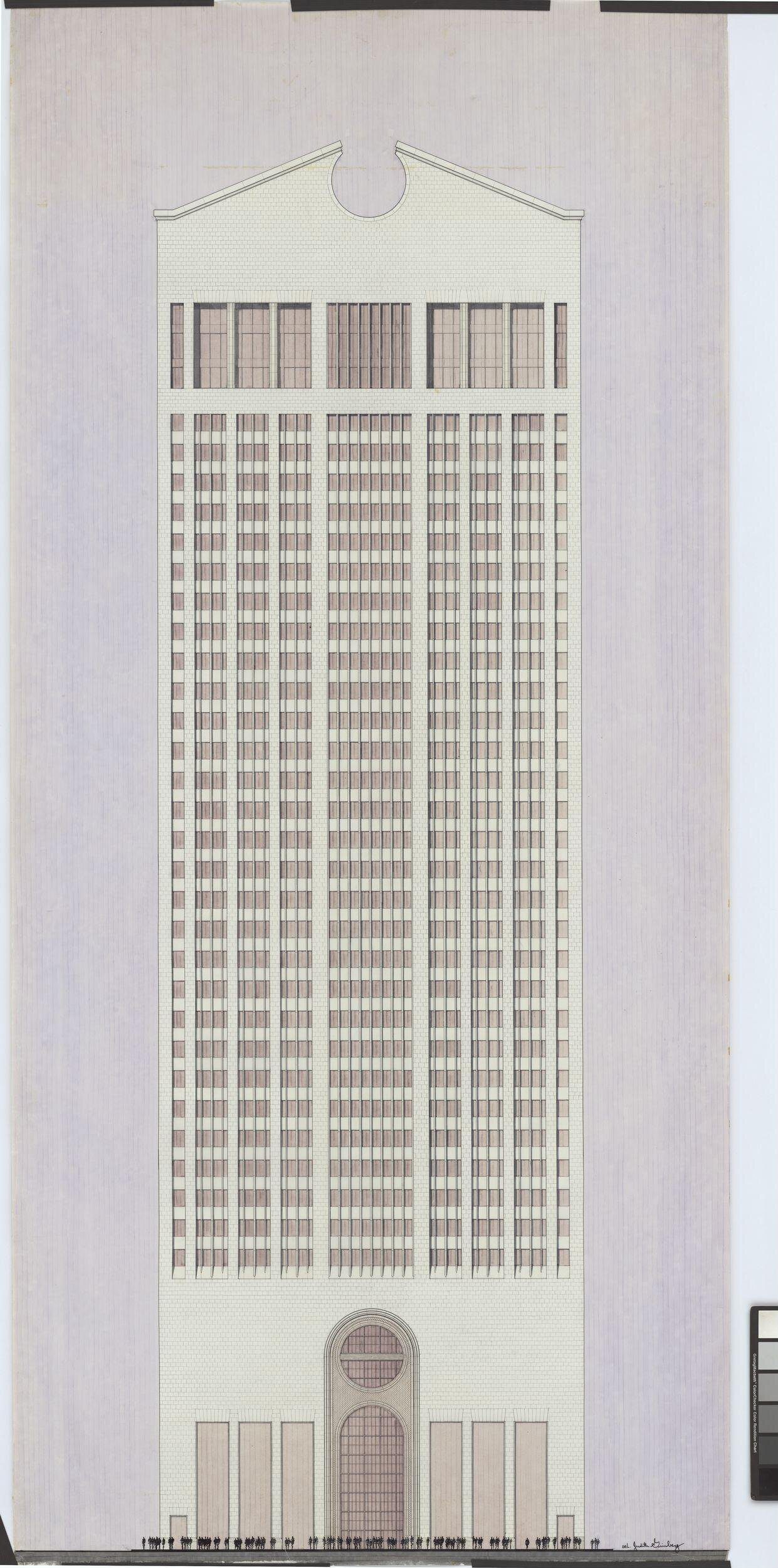

The movement that challenged modernism at the time, such as postmodernism, was clearly named after the ideology against which it reacted. The high-rise AT&T Building (1984) in New York City is one of the most prominent and globally renowned postmodern architectural creations. It was designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee, who incorporated elements of Western classical architecture, such as the use of an arch in the podium design and the pediment as the building’s crown. The design challenged the high-rise, glassy, box-shaped structures dominating the city’s skyline criticized for their monotony and overly functional designs. One of the prominent examples in Thailand is the Amarin Plaza Shopping Mall (1984), where the architect, Rangsan Torsuwan, employed elements of classical architecture, especially the ionic order of Greek architecture, to accentuate the building’s luxurious and majestic image. The design was so impactful that it enticed business owners to reserve retail spaces with a 100% down payment even before the construction had started, compared to the building’s initial design, which was Modernist and drew few to no buyers.5

A globally recognized example of Postmodern architecture, the AT&T Building (1984) whose architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee incorporated elements of Western classical architecture, from the arch applied to the Podium to the pediment as the building’s crown. | Photo courtesy of Victoria & Albert Museum, London

One of the prominent examples of Postmodern archtiecture in Thailand is Amarin Plaza Shopping Mall (1984) where the architect, Rangsan Torsuwan employed elements of classical architecture, especially the ionic order of Greek architecture to accentuate the building’s luxurious and majestic image. | Photo: Shutterstock / iFocus

It wasn’t that Modernism completely ceased to evolve at the time, but the world saw the birth of a new type of architecture known as High-tech Architecture.” The Centre Pompidou (1977) in Paris, designed by a team led by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, is an example of this architectural style, as is the HSBC Headquarter in Hong Kong (1986), designed by Fosters Associates. The main structural components and system works were pushed toward the perimeter, following the architects’ intention to create flexible and adaptable interior functional spaces. The structure, components, and building systems made their presence known with shapes and forms that demonstrated their weight-bearing and functions, while the bright, vibrant colors were those of industrial materials such as steel, etc. The glass was custom-made and prefabricated at the production facility before being assembled on-site6 . Another notable work is the Science Museum (1977), where Dr. Sumet Jumsai designed for the main conference hall’s reinforced-concrete structure to protrude 15 meters from the building to accentuate the main entrance. The main exhibition room was formed using steel trusses and curtain walls supported by steel structural frames, while several parts of HVAC systems were purposefully left exposed. All of these factors led to the museum being classified as High-tech architecture in Sir Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture (1987 edition), one of the world’s most prestigious architectural history books7 . The building is Thailand’s first modern architecture to be featured in this book.

In fact, the first time modern architectural creations from Asia were featured in this important publication was in the 1975 edition, and all of the works were from Japan. It was in its 1987 edition or 19th edition that the book began to include works from other Asian countries, such as India, Bangladesh, and Thailand8. This fact leads to the observation of how modern architecture has always been perceived as a product of the Western world, which “The Others” outside of that world adopted and applied to fit their own contexts. Such a western-centric viewpoint held that it would be difficult for modern architecture outside of Western countries to be decent, special, or innovative. The architectural projects selected were either designed by Western architects, such as the works Le Corbusier designed in India or Louis Kahn worked on in Bangladesh, or they were works that were viewed as references of Euro-centric innovative approaches, such as Dr. Sumet Jumsai’s High-tech architecture, which, at the end of the day, is still classified as ‘regional,’ or something that branched out from the ‘originals’ that were created in the west; something that was adapted to better suit the site’s limitations and contexts.

It was amidst such an architectural climate in Thailand and the world, as well as the status of architects from Thailand and Asia discussed earlier in this article, that the Robot Building was born. Because the design concept of this built structure was a question directed at and challenging the new emerging ideologies, whether it be High-tech architecture or Postmodern Classicism, the concept behind the inception of the Robot Building, therefore cannot easily be classified as Postmodern or Modern. This is possibly the first time that a Thai architect’s work has been sent out to the world’s stage, challenging world-renowned works of architecture.

The Centre Pompidou (1977) in Paris designed by a team of architects led by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers| Photo: Julien Fromentin

The HSBC Headquarter in Hong Kong (1986) designed by Fosters Associates | Photo: Wikimedia Commons / WiNG

The book Robot Bank: A Statement in Post-High-Tech9 published by Asia Bank in 1987 had Dr. Sumet Jumsai’s architecture firm handle the contents. It defined the Robot Building as a “post-high-tech” architecture for its progressive visuals that were still very much public-friendly. The author stated that such characteristics extended beyond the beauty of technology, machinery, and structure found in the High-tech architecture such as the HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong, which was completed in the same year as the Robot Building, or even the Centre Pompidou, whose construction was finished less than ten years prior.

The book also included an interview transcribed from Dr. Sumet Jumsai’s “Why the Robot” lecture at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand. The entire lecture was later published as an article in Mimar Magazine, Asia’s most prestigious architectural publication at the time, titled “Building Study: Bank of Asia, Bangkok”10 . In that article, Dr. Sumet Jumsai provided an elaborated and detailed critique of High-tech architecture, citing both the HSBC Headquarters and the Centre Pompidou and stating that while the two buildings attempted to demonstrate advanced technological progress by putting system works and structural components toward the perimeter, the construction and assembly of all these prefabricated structural parts and components still relied heavily on highly skilled and experienced workers. For Dr. Sumet Jumsai, there were certain limitations that came with the buildings’ ‘High-tech’ characteristics and genuineness and their expressions of what constituted as true High-tech architecture. When that was the case, he instead opted to communicate what High-tech conveys.

Photo: Beer Singnoi

The discussion of ‘conveyed meanings’ leads to the debate over postmodernism. The Robot Building’s form and elements hold an aspect that challenges postmodern classicism as well as other facets that demonstrate its existence as a partial product of modernism. In his ‘Why the Robot? lecture, Dr. Sumet explained the first aspect by referencing major works of postmodern classism both inside and outside of Thailand. He questioned why there couldn’t be a Robot Building if the world had already seen “the grandfather’s clock” and “the Acropolis in downtown Bangkok” (presumably referring to the AT&T Building in New York and the Amarin Plaza shopping mall, respectively). Dr. Sumet criticized Postmodern Classicism for combining various elements of the past before pasting them on a building and presenting them as something new, when there was, in fact, nothing new about it but rather a contrived attempt to recycle something that was even older than Modernism.

The comments that the Robot Building was partially a product of modernism stemmed from the utilitarian properties of many of its components, or the interior functions. Despite being expressed in abstract forms that accentuate the robot-like image of the buildings, these components, such as the bolts and caterpillar wheels, also function as windows and the canopy covering the side entrance. Not only that, but many other elements were designed to suit the hot and humid climate and provide easier maintenance, such as the opaque east-and-west-facing walls or the overhanging canopies facing north and south, which allow for easier cleaning and maintenance of glass windows. These parts contain their own functional purposes, but they also serve as the side of the robot’s body, and lines that resemble a robotic circuit.

Photo: Beer Singnoi

The aforementioned comparison made by Dr. Sumet, the architect who designed the building, between modern and postmodern classicism architecture reflects his belief that the Robot Building could be the most progressive and cutting-edge idea that the global architectural community has ever seen. The scenario of the international architectural arena at the time when an architect from a third-world country emerged with a unique design that had never been thought of or done before and criticized the works of internationally renowned Western architects was almost unprecedented. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Robot Building was the catalyst for Thai architects’ gaining global recognition11.

Dr. Sumet’s criticism of postmodern classicism and High-tech architecture did not end there. He saw the Robot Building as the first step in the evolution of architectural ideation that would continue for generations to come. Dr. Sumet went on to say in that same lecture that, while Robot Building was new and unprecedented, what he saw as even more important was that it didn’t have to be a robot and that architecture in the future could be pretty much anything that could bring a society an even better and more progressive future. Dr. Sumet, on the other hand, saw ‘robot’ as a clear representation of the relationship between man and machine and predicted that the two would become even closer in the future. When the lecture was given in the 1980s, the greatest example Dr. Sumet had seen was how one drives a car. When a person begins to learn how to drive, the car and the mechanism it is made of are foreign to human experience. However, as a driver’s skill develops and experiences are acquired over time, they are able to command their mind and body to adeptly mobilize the vehicle, as if the human body, the car, and all the mechanisms worked in unison.

Dr. Sumet went on to say that within the first half of the next century, humans and machines would be unified into one, and that in the latter half of the century, revolutionized communication would not be ‘bound by physical properties and thus limited to the speed of light, but would expand across the real and virtual worlds.’ It’s interesting that at this point in time, two decades into the new century, many of the things Dr. Sumet predicted would happen in 100 years have already happened within the span of only twenty years, not to mention how they’ve become so intertwined with architecture. AI has been developed to aid in the design and construction of various types of smart buildings, as well as to accommodate or adjust the interior environment to best suit human users’ physical conditions, needs, and preferences. Space and architecture are being created, used, and purchased in virtual worlds such as the metaverse. If we consider AI, smart technologies, and the metaverse to be parts of the architectural evolution that has continued since the birth of the Robot Building, what remains unclear or the same are their forms, given how every type of architecture can be intertwined with the aforementioned evolutions. Perhaps this is confirmation that it indeed doesn’t have to be a robot, because it can be anything.

Photo: Shutterstock / Nbeaw

Despite the fact that the architecture of the next generation could be pretty much anything, architecture is still fundamentally made up of space and form. And, returning to the issue of the search for a novel form, it is undeniable that the Robot Building was unprecedented in terms of architectural form. Dr. Sumet stated at the end of his lecture that the Robot Building was only the first step. At the end of the previous century, there was an attempt to end people’s alienation from machines, with the end goal being the vision that machines would be like friends—something we would grow accustomed to and become a part of our daily lives; something that would be on our side. This last topic led to one of the key questions written on the final page of the ‘Why the Robot?’ article.

To the question of whether the Robot Building had any Asian characteristics or not, Dr. Sumet’s response was that Asian or national identity could be an inferiority complex caused by external threats or influences. It influenced people in a particular nation to desire what they feel that they do not have, which in this case was the aforementioned Asian or national identity. Dr. Sumet, on the other hand, believed that each individual or group of people possess their own unique identity and that the attempt to understand all of these different identities should be done from an anthropological perspective, which would provide a more profound take rather than simply looking at something from its physical forms and elements, the latter of which often produces, in Dr. Sumet’s words, “the oddest pastiche imaginable.” Nonetheless, Dr. Sumet believes that the Asian identity is present in the Robot Building to some extent because it makes machines look and feel more humanized and friendly. He compared it to how Thais decorate their Tuk Tuks and long-tail boats, as well as how Filipinos adorn their Jeepneys.

Tuk Tuks | Photo: Shutterstock / Hit1912

Jeepneys| Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Lawrence Ruiz

The interconnected relationship between the Robot Building and long-tail boats, tuk-tuks, and Jeepneys piqued the interest of one of The London Times’ readers, John Leech, who wrote to the editorial team citing “The world’s first robot-shaped building” published earlier on December 7th, 1986. In his letter, he stated that the case of long-tail boats, Tuk Tuks, Jeebneys, and The Robot Building was a great example from Southeast Asia that Westerners should study to understand how ideas, technologies, and human developments were integrated as a collective whole rather than separate entities.

In short, the Robot Building is an architectural creation from the 1980s that not only challenged global architectural movements such as modernism, postmodern classicism, and High-tech with its post-high-tech ethos, which combines cultural concepts and communication with humanness in those progressive, cutting-edge ideas, but also stood against the Western world’s monopolization of cultural and artistic expressions as well as technological architectures. Most importantly, the challenge was communicated in a universal language by an architect from a country that has historically been regarded as “The Other” in the international architectural arena. As a result, the Robot Building is not only a milestone in the transition between globally mainstream architectural movements but also a significant turning point in the role and status of Thai architects in the global architectural community.

Photo: Beer Singnoi

1 Docomomo_Thai. 2023. Facebook.

2 Singnoi, Weerapon. 2023. ‘Save our fading modern architecture’, Bangkok Post, 30 March 2023, section OPED.

3 Lassus, Pongkwan. 2023. “An Open Letter to the Executives of UOB Thailand.” In.Bangkok.

4 Curtain Walls and Concrete Façade, What’s Better : A Debate over Two Modernist Approaches in 1981’s Thai Architectural Industry’ in. 2008. Keeping up Modern Thai Architecture 1967-1987. (Thailand Creative & Design Center: Bangkok).

5 Bhumichitra, Piyapong. 2017. ‘Rangsan Torsuwan: One of Thailand’s Most Influential Educators, Architects, Real-Estate Businessmen (1)’, Accessed 4 April. https://themomentum.co/successful-opinion-rangsan-torsuwan/.

6 ‘High Tech’. RIBA, Accessed 4 April. https://www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/high-tech#.

7 Sir Banister Fletcher’s a History of Architecture. 1987. (Butterworths: London).

8 Fusinpaiboon, Chomchon. 2014. “Modernisation of building : the transplantation of the concept of architecture from Europe to Thailand, 1930-1950s.” PhD. Dissertation : University of Sheffield.

9 ” ROBOT : a statement in post high-tech.” In. 1987. Asia Assets.

10 Jumsai, Sumet. 1987. “Building Study: Bank of Asia, Bangkok.” In Mimar : Architecture in Development, 74-81. Singapore: Concept Media Ltd.

11 Rujivacharakul, Vimalin. 2004. ‘Bangkok, Thailand.’ in Sennott R. Stephen (ed.), Encyclopedia of 20th-century Architecture (Fitzroy Dearborn: New York, London).

Photo: Beer Singnoi

Photo: Beer Singnoi