AMONG THE HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE VILLAGES FOR THE HAKKA IS A LIGHT-BLUE BOXY PAVILION BY HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH THAT CONNECTS WITH THE HISTORY, COMMUNITY, AND CULTURES

TEXT: KORRAKOT LORDKAM

PHOTO: YU BAI

(For Thai, press here)

Dawan Shij, also known as the Dawan Ancestral Residence, is a place of historical significance for the Hakka Chinese people. Dawan Shiju, located in the Pingshan district of Shenzhen, China, was one of the key locations of the 2022 Urbanism\Architecture Bi-City Biennale (UABB) of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Among the historic residential structures, the light-blue boxy pavilion stood out. The pavilion, titled “Freeing FrameYard,” is the work of Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee of HAS design and research. It was one of the most notable built structures in the neighborhood, owing to both its location and its concept, which attempts to connect the history of the site to new elements of design.

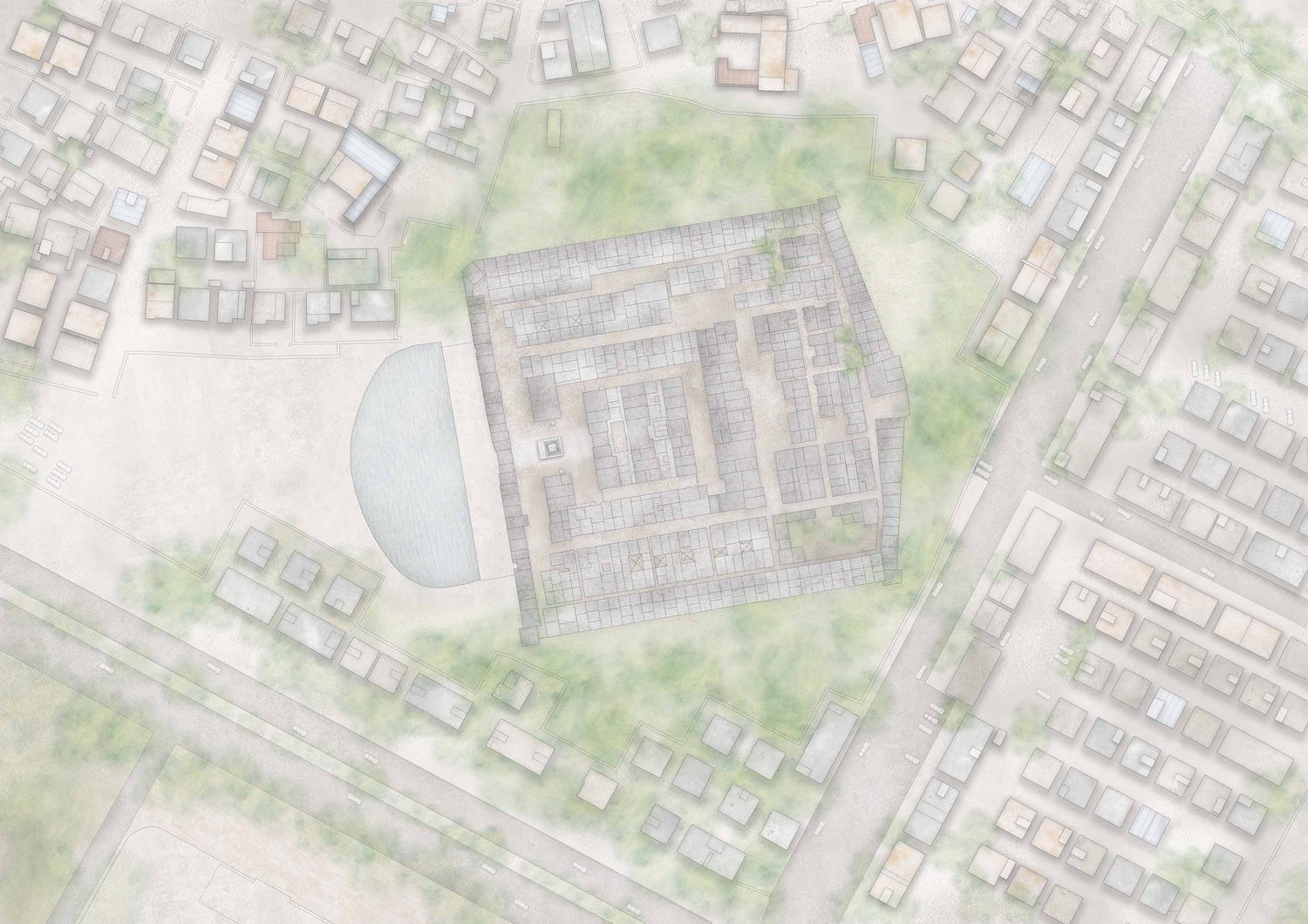

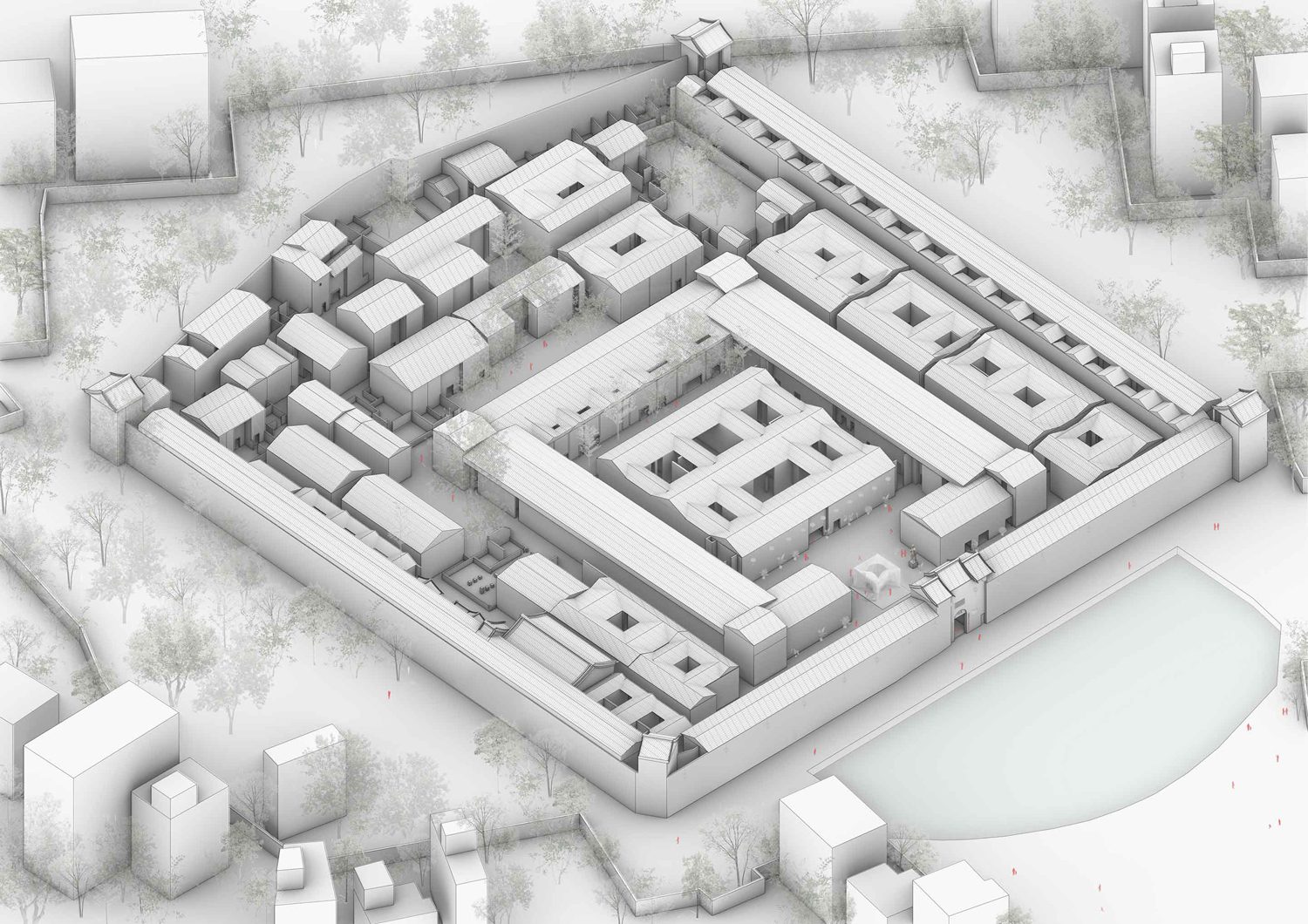

Dawan Shiju was constructed in the 1790s and was formerly a residential complex with approximately 400 living units. With all of the residents long gone, the buildings have been turned into a conservation site that welcomes visitors as a traveling destination. Despite its now-changed status, the Hakkas who live in the vicinity have used the site to organize traditional and cultural activities. Dawan Shiju’s architectural traits are made up of blocks of brick dwellings constructed in orderly clusters and rows. All of the structures were built within the walls, with a big pond in the front, creating a landscape similar to that of a castle. Within the visibly organized site plan are the residential buildings, constructed in orderly and symmetrical clusters. The enclosure and carefully designed site plan are common features that most Hakka villages in various regions of China appear to share, coinciding with their history, which is made up of multiple major migrations (the implication can be found in the name Hakka, which translates to “visitors” in Cantonese).

Shenzhen is not only one of the first areas where Hakka Chinese settled, but it is also one of the first cities to be included in China’s special economic zone. This has resulted in the city’s progressive transformation and elevated it to the status of one of Guangdong Province’s most advanced metropolises. Kulthida stated that the UABB, in which her office took part in 2019, chose venues in industrial zones to help revitalize the neighborhood and attract visitors through the help of art and design initiatives. What’s particularly intriguing about the 2022 event is the organizer’s plan to include venues with historical significance and associations with the ways of life and cultures of specific groups of people.

Site plan © HAS design and research

In the big picture, the architect discussed the brief they were given and the event’s ‘Unplugged’ concept, which holds multiple interpretations in and of itself. For the organizer, the word could mean a digital detox that allows people to experience tangible things with their human senses, or it could refer to saving or reducing energy consumption, as well as a removal of frames and limitations that are tied to all forms of belief that allows for a peaceful coexistence for all.

“We started by looking at the location’s unique character.” Kulthida recounted the design’s genesis in an area of such meaningful history. “We discovered that each old building has its own ‘courtyard’ as one of its distinguishing features. When you walk into a house, you’ll find yourself standing beneath an eave, with a courtyard in the center.” There’s also the idea of a series of connected courtyards, which is one of Hakka Village’s distinctive characteristics.”

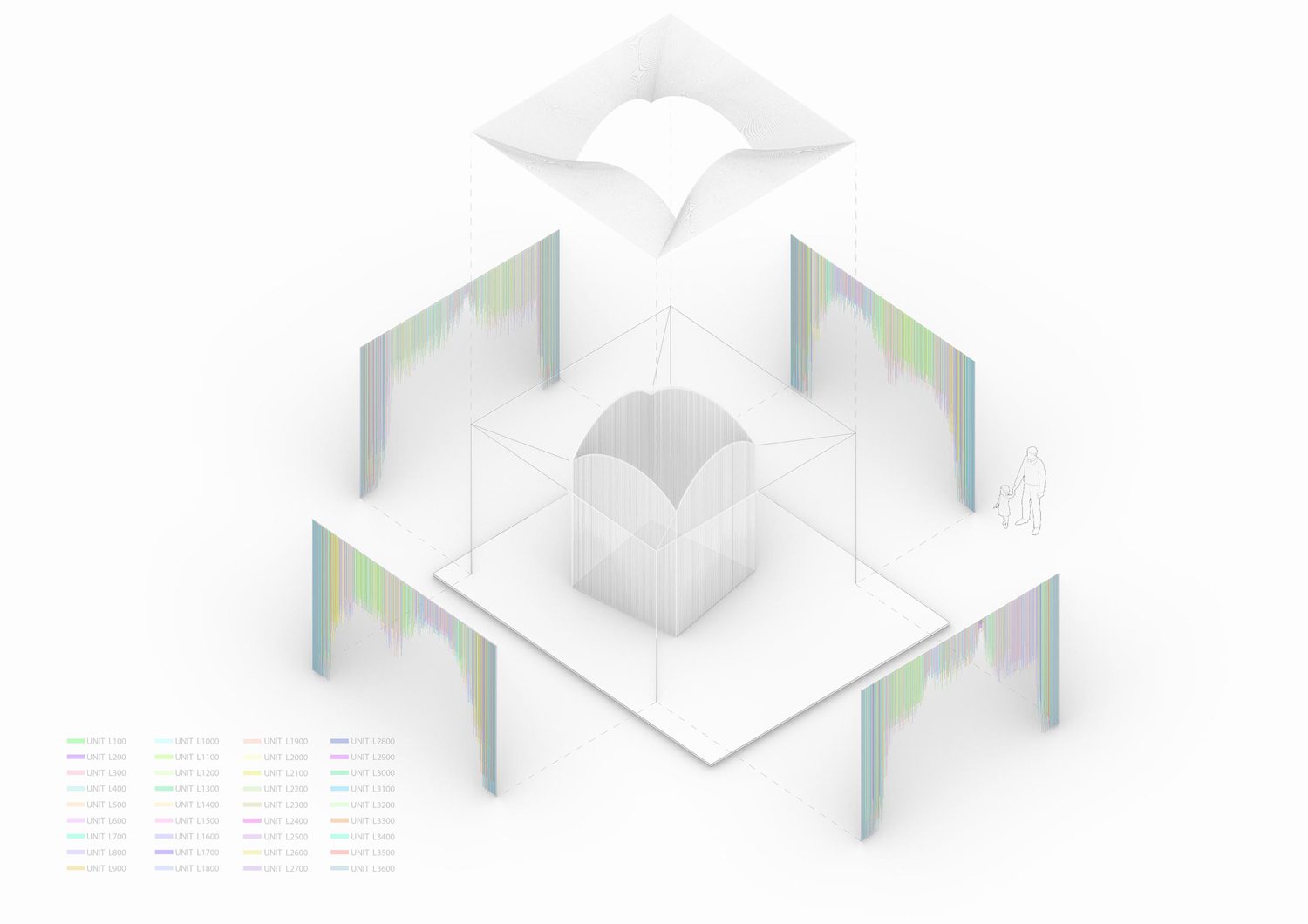

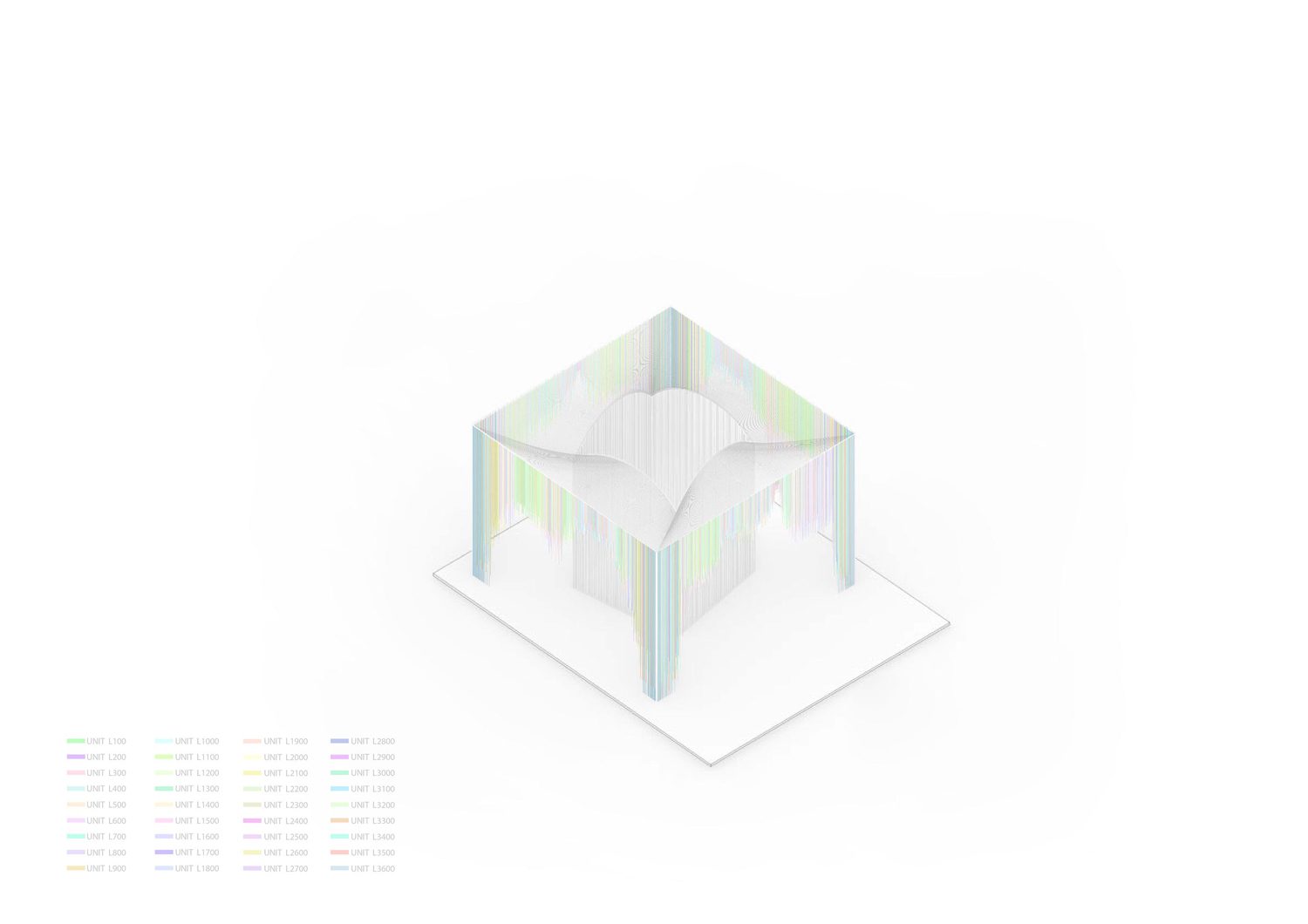

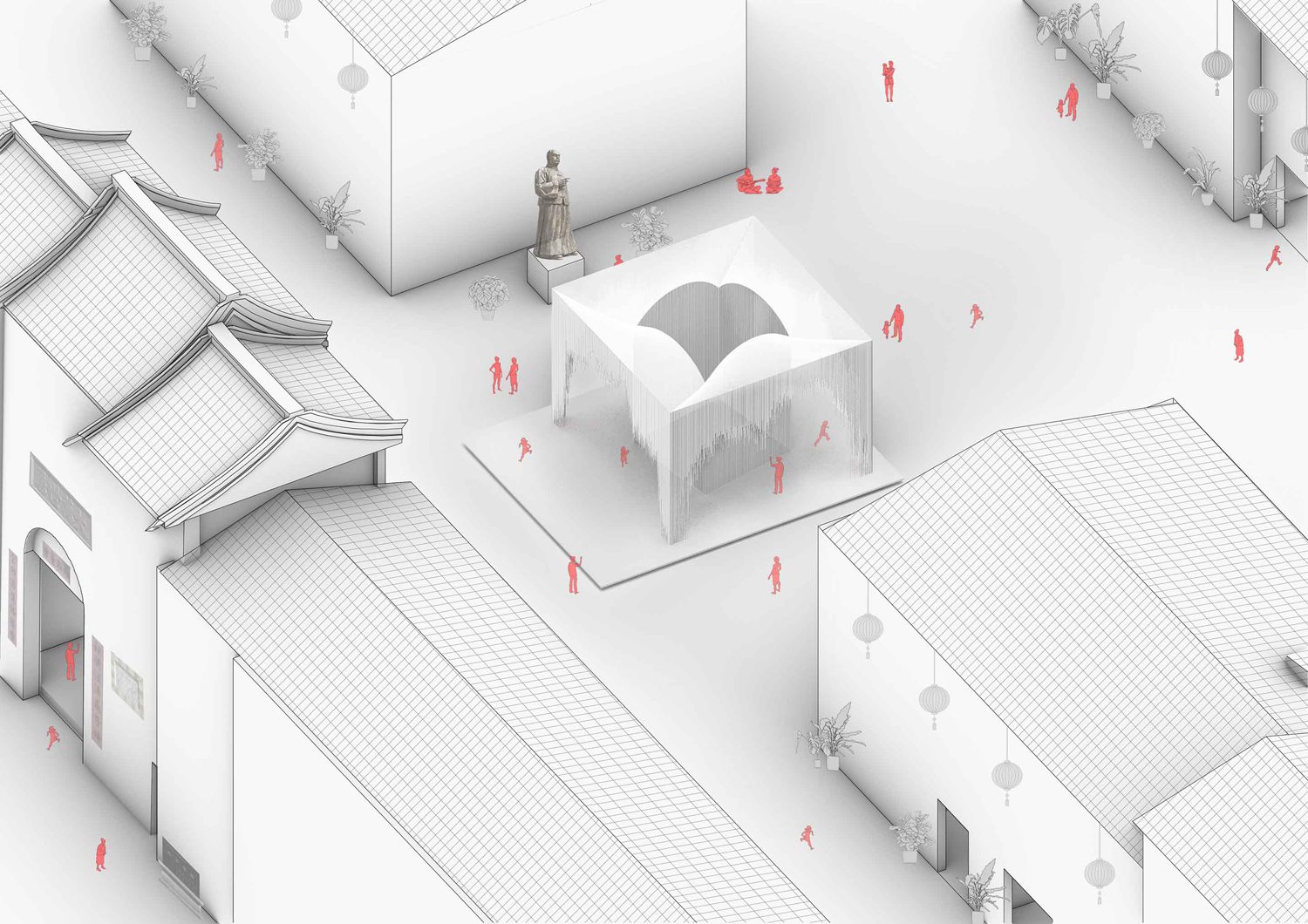

Isometric © HAS design and research

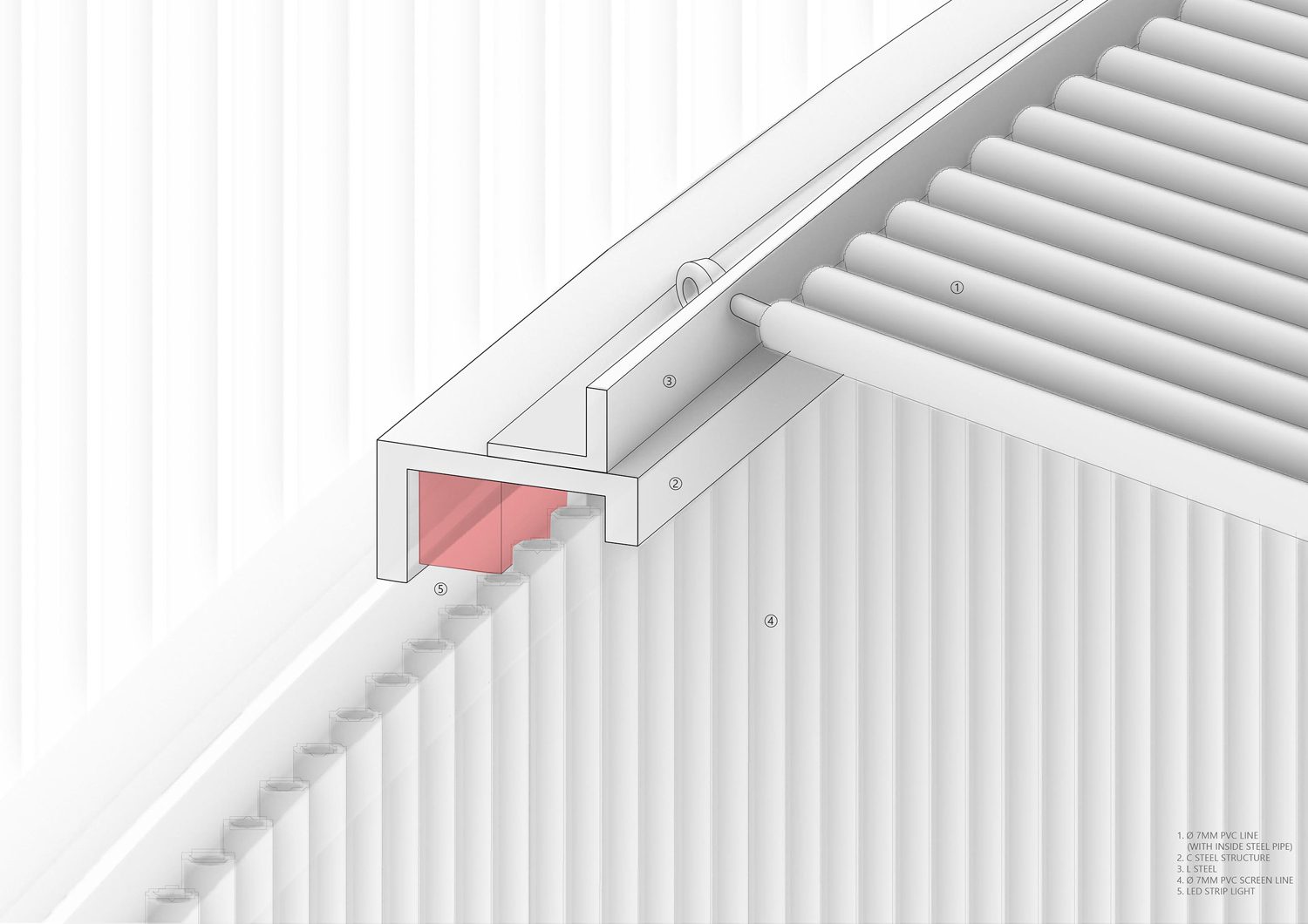

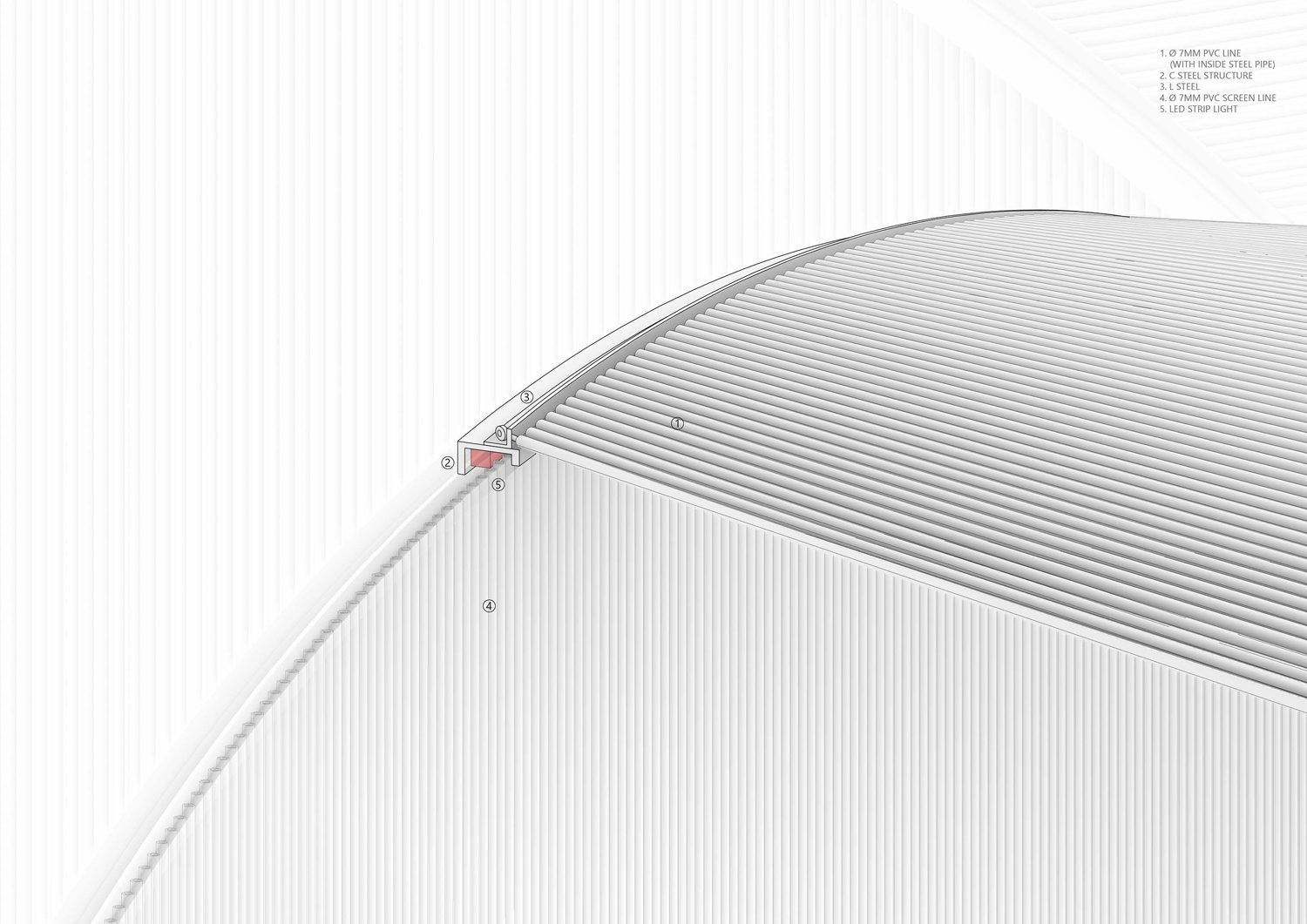

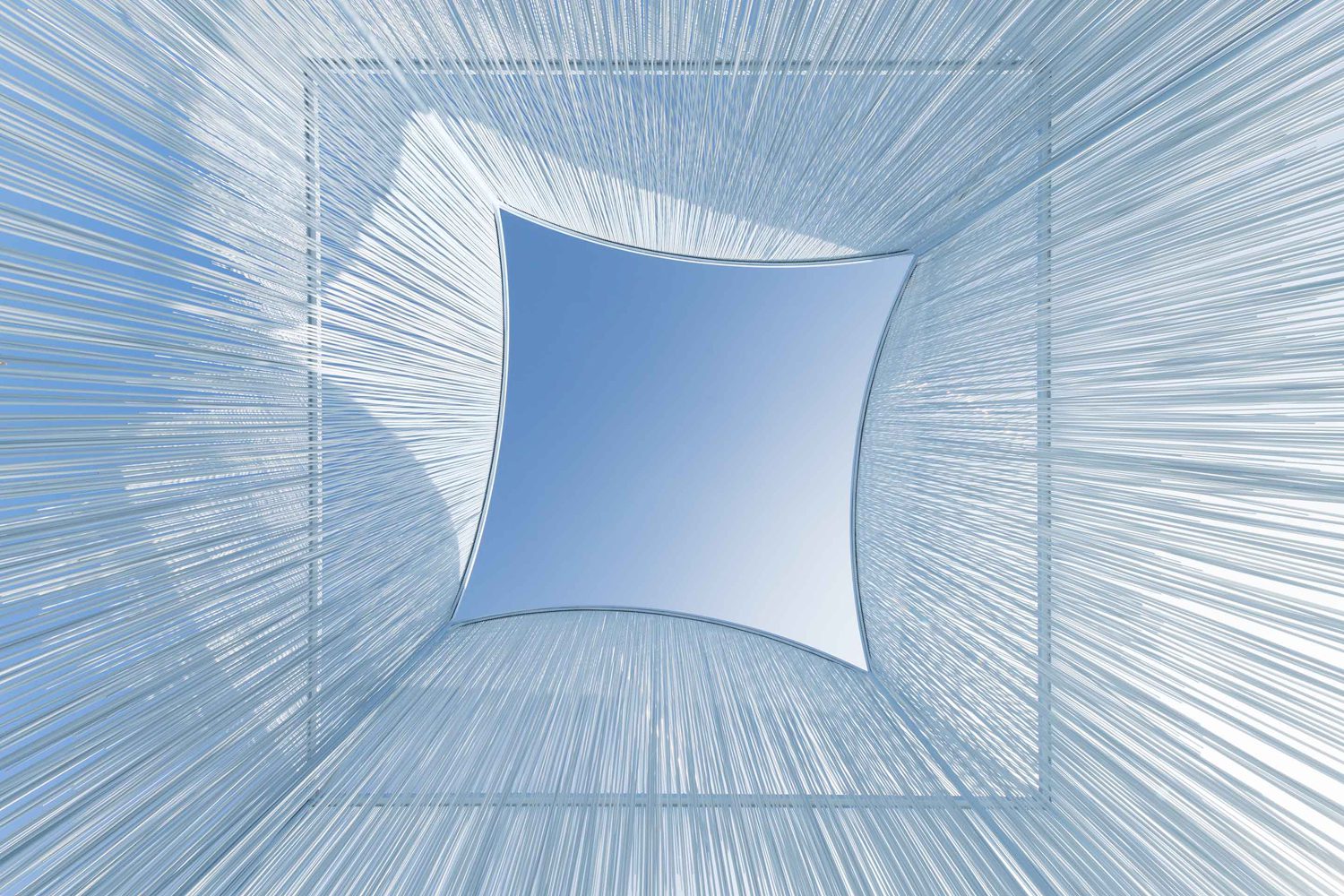

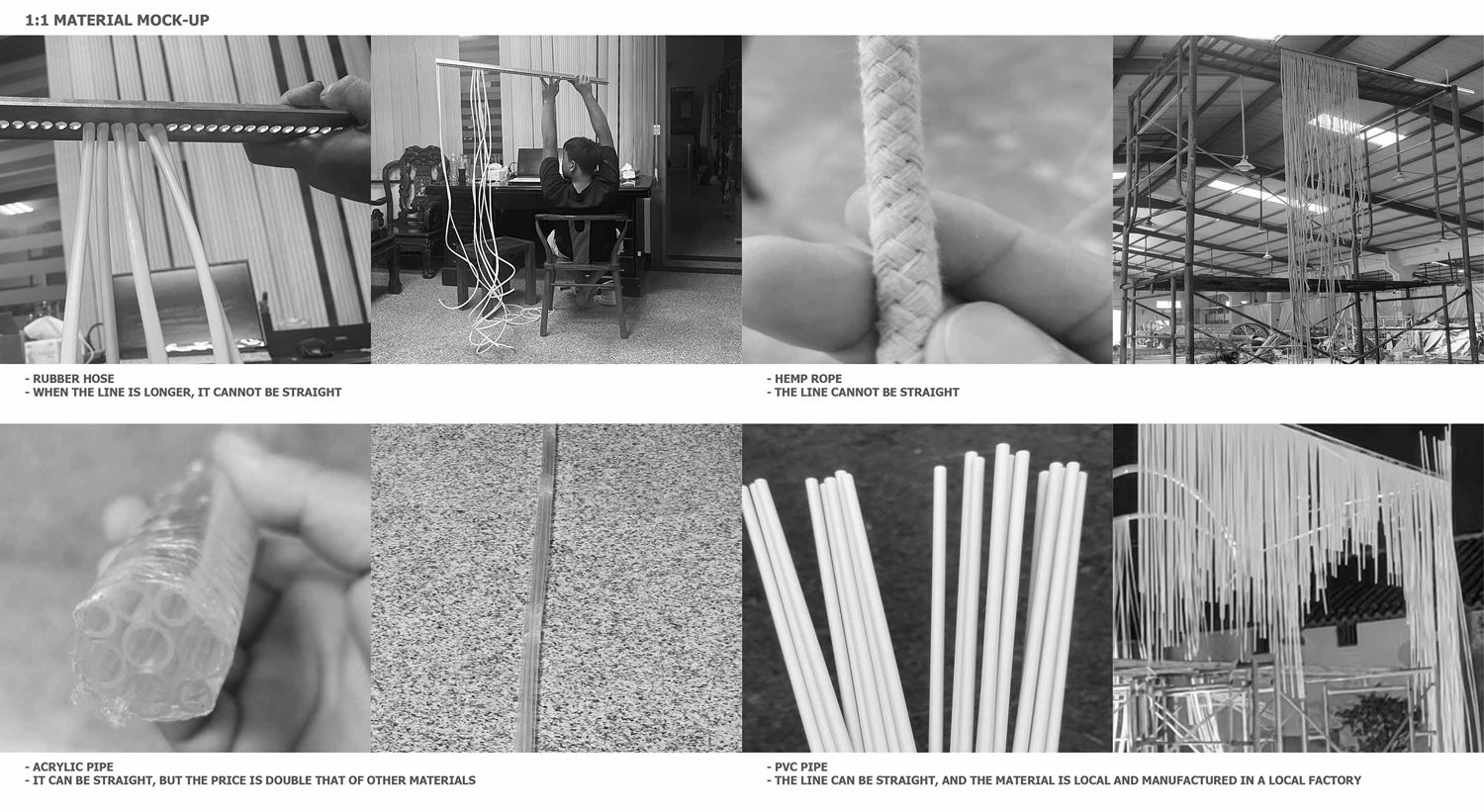

Kulthida noted that the unoccupied land on which the pavilion will be built carries as much significance to the community and the former owner of the land as the UABB event itself. Simply put, the area had been designated as a UABB site and would be used as a stage or backdrop for various activities and exhibition openings. Not only that, the brief also stated that the previous owner of the location, the Hakka Chinese community, will be able to use the area for local festivals and events such as Chinese New Year, like they always have, even with a UABB event happening. Due to the necessity for the site to remain flexible, the entire pavilion would need to be dismantled and reassembled in a short amount of time. With these requirements in mind, as well as the desire to incorporate the key physical features of a courtyard in a typical Hakka residence, the architects translated everything into a 3.6-meter-high, 5×5-meter steel-structured pavilion. The architectural form is made up of 5,000 tiny PVC pipes with a diameter of 7 mm. The pipes are suspended, forming a sequence of curtain-like structures that enclose the room. The enclosure was first built with two layers of PVC pipe curtains. The outermost layer is made up of varied lengths of plastic threads arranged into a façade whose intricacies are a play on the differing appearances of the buildings surrounding the pavilions’ four sides. This layer of curtains is left to hang above guests’ heads, providing a sense of enclosure while transitioning visitors from the outside world into the semi-indoor space of the pavilion.

The reconfiguration, which results in both open and closed curtains, corresponds with the work’s location. Openings are necessary for both statues to still be visible because nearby ancestor sculptures are well-known and cherished by the community. The inner layers of the curtains are composed of plastic elements with the same floor-to-ceiling length, and a 2.4×2.4 m structure was covered behind them. The style of the doorways of the nearby historic buildings served as inspiration for the curtain’s arch-like design.

The architect explained how the use of different materials to represent the history of the place was an attempt to express an additional aspect of the surrounding architectural structures through the access and transition between spaces. Similarly to how each of these historic buildings conceals its courtyard, covering the pavilion’s area with plastic drapes creates an open ‘courtyard’ that brings the presence of the sky into the pavilion’s space. Not only that, the inner space is an implied expression of an idea, which chooses to deviate the courtyard’s angle from the main core of the pavilion and the site’s vertical axis. We wanted to propose an idea of how new elements could be included and presented as part of things that are reflective of a pre-existing context or creation.

A pavilion with a comparable color to the sky was the end result of the entire thought process. It’s a pavilion that presents the original architectural characteristics of the site through new components or a different form of design. According to the architect, such a reference may be traced back to the design team working closely with the Hakka people, who were the former owners of the place. Not only does the pavilion enable the formation of its relationship with the surrounding environment of historical buildings, but it is also an attempt to build a connection with the existing community and cultures.

This idea is consistent with what Kulthida described. “We want the pavillion to communicate with people who visit a historical village such as this one that, while a work may not speak to them in a direct and tangible manner, they should be able to pick up on or imagine, for example, whether what they see is actually an old entrance door or whether it is an old component that is applied to or used differently in more contemporary works of design.

“For the work to represent the ‘unplugged’ theme, it should be about unplugging the old and introducing the new. There needs to be some new qualities added to the design, whether in the form of spaces, design components, or even the materials.”

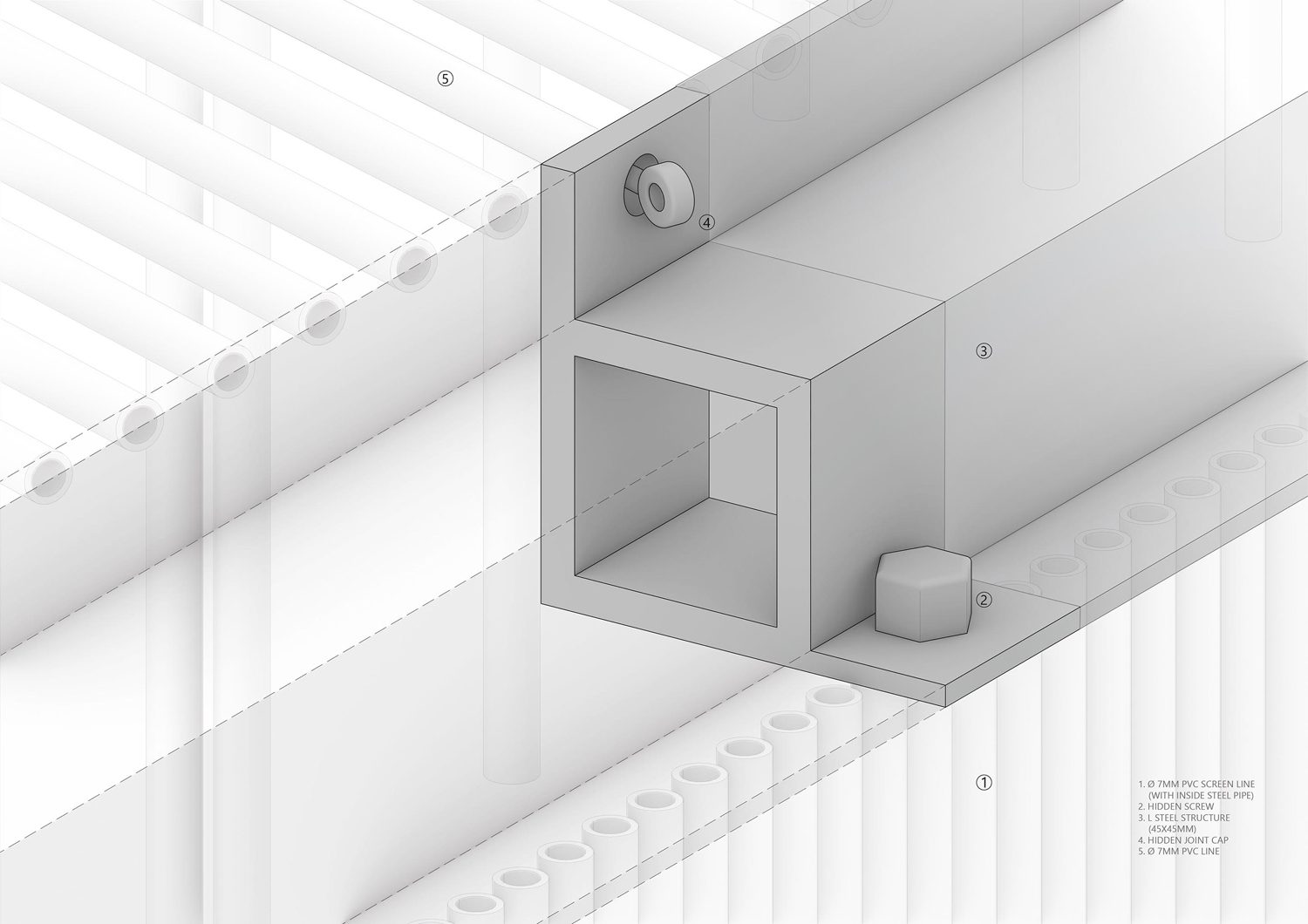

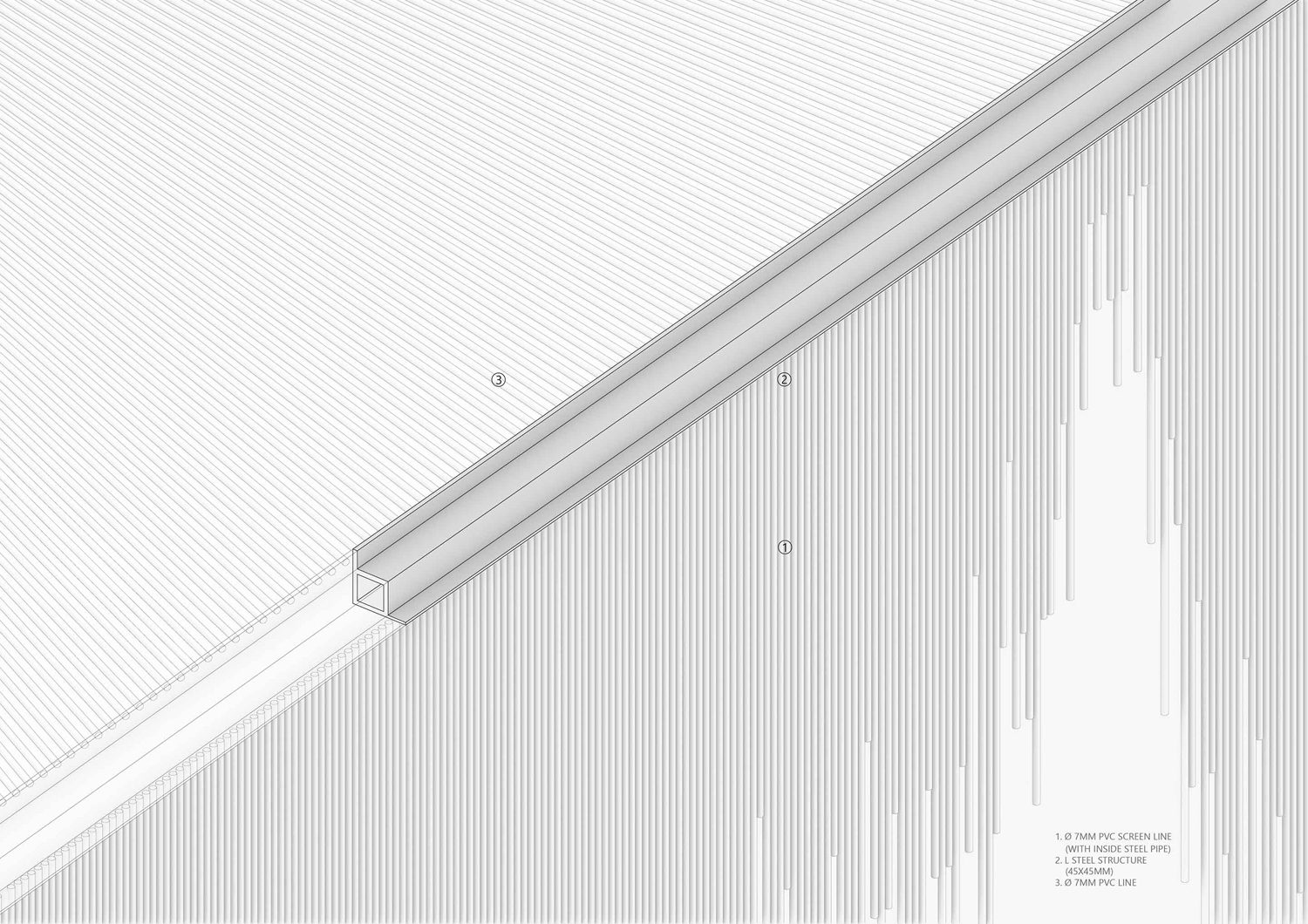

Material mock-up © HAS design and research

For the architect, this aspect of the project encompasses many different aspects of what “unplugged” stands for, apart from the actual act of disconnecting or unplugging something, such as how the pavilion may be disassembled and reconstructed to suit the conditions or context of the site. With this pavilion, traditional architectural characteristics have been unplugged to simultaneously allow for new meanings to emerge through a new creation of architecture.

hasdesignandresearch.com

facebook.com/hasdesignandresearch

Citation

Siripen Ungsitipoonporn, Meaning and Identity of Hakka, Silpakorn University Journal, Volume 33, Number 1 (January-June): 215-240, 2013

Nicole Constable, Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad, University of Washington Press (February 1, 2005)