AS ONE OF THE MIXED-USE BUILDINGS IN A LARGE-SCALE URBAN EXPANSION PROJECT IN AMSTERDAM, THE PROJECT WAS DESIGNED TO COMBINE VISUALLY APPEALING ARCHITECTURE WITH SUSTAINABLE LIVING THAT WAS INTENDED TO BE THE TOWN’S ‘LIVING ROOM’

TEXT: KORRAKOT LORDKAM

PHOTO: SEBASTIAN VAN DAMME

(For Thai, press here)

IJburg is a large-scale urban expansion project on the outskirts of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The new residential area, which was proposed in 1997, would be constructed on artificial islands in Lake IJmeer, the country’s largest lake. The project, which is the result of a collaborative investment between the country’s public and private sectors, aims to increase the capital city’s urban space to meet the growing population and demand for residential spaces. The planned urban neighborhood development will have 18,000 dwelling units and house roughly 45,000 inhabitants. The first building on IJburg was finished in 2001, with the first group of residents occupying the space in 2002¹. IJburg’s development is still going on, with new residential complexes continuing to emerge. Among the completed projects is ‘Jonas,’ a major innovative housing development by developer Amvest with architectural design by Orange Architects. Completed in 2022, Jonas is designed to combine visually appealing architecture with sustainable living.

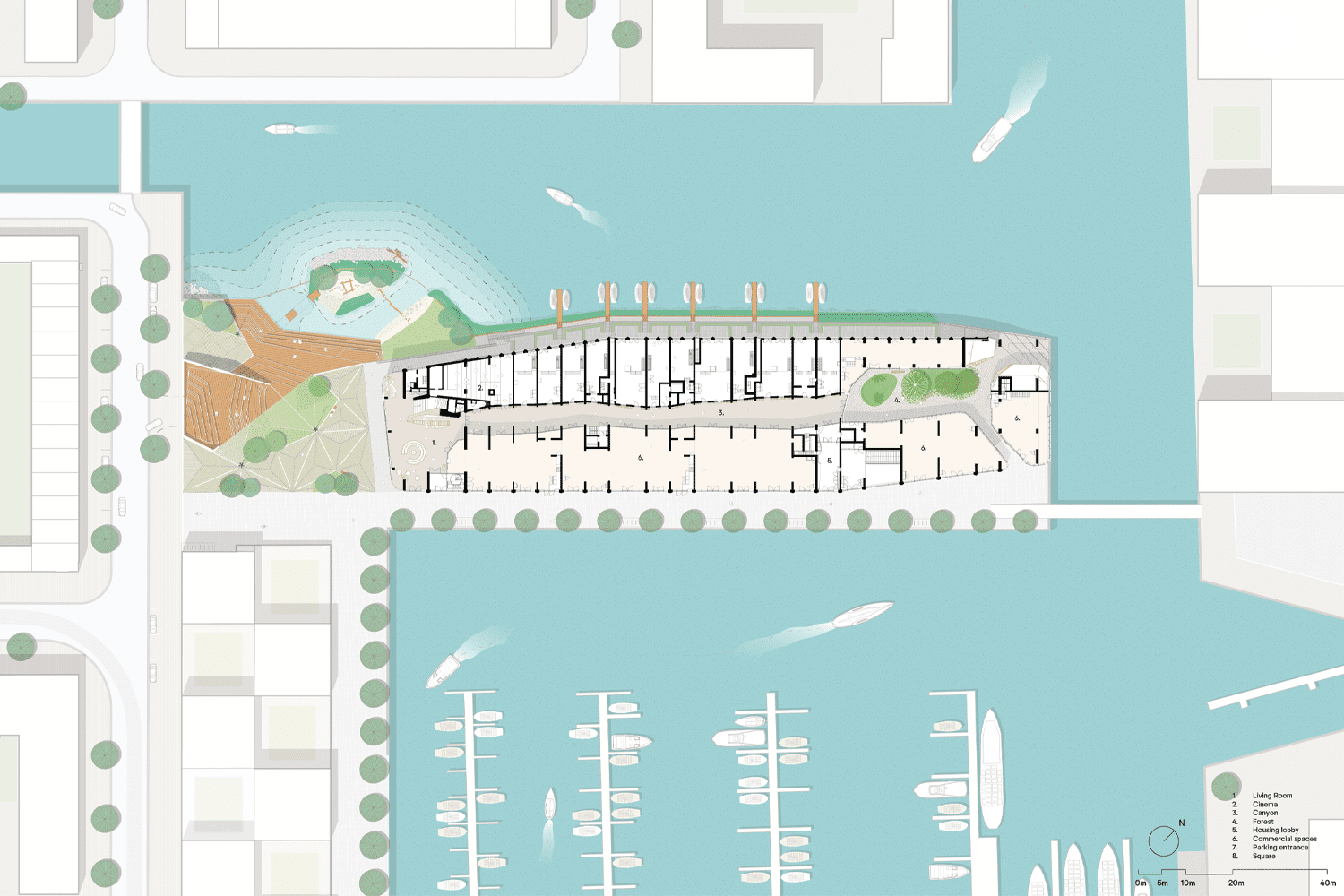

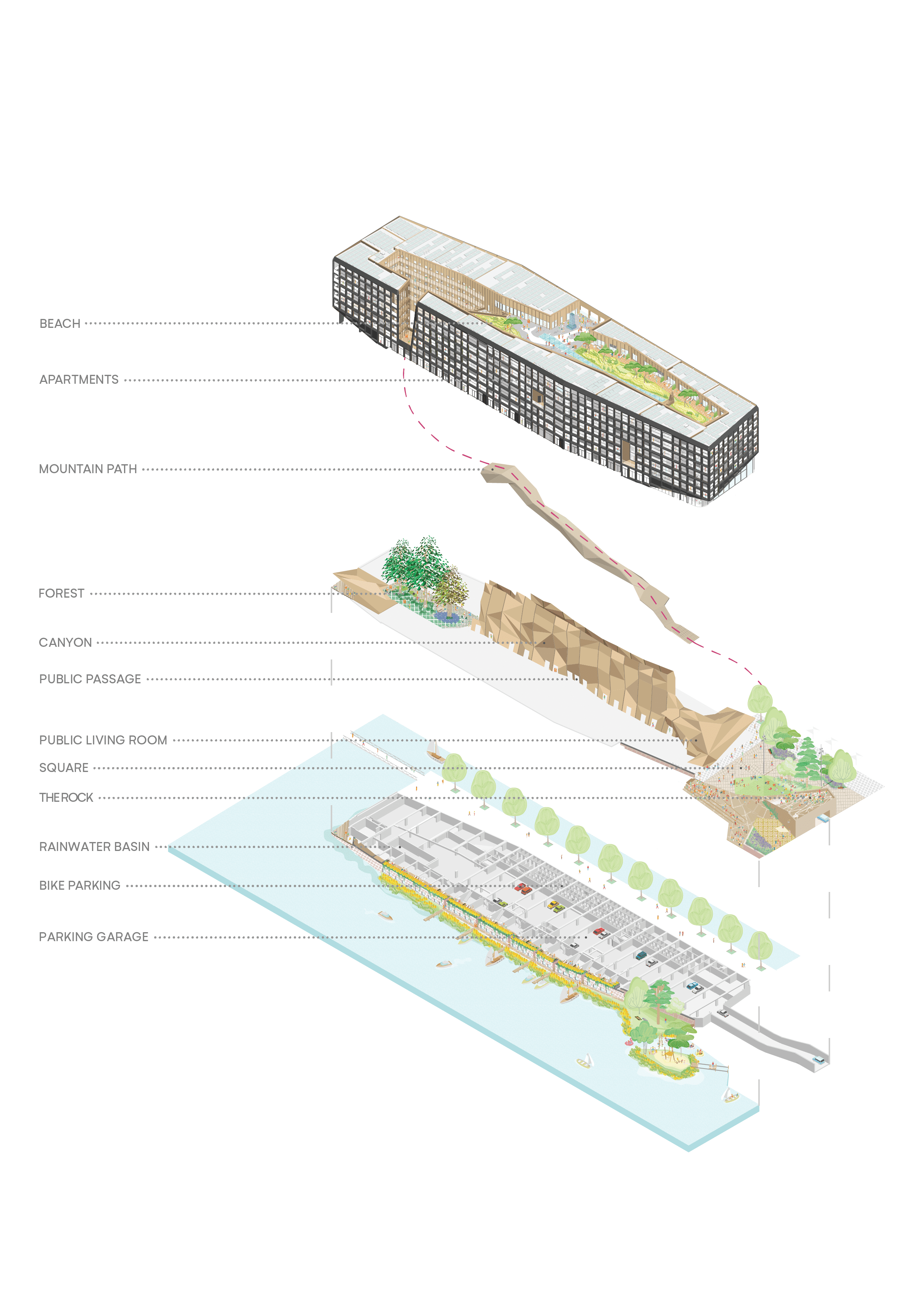

Jonas is a 30,000-square-meter mixed-use residential project located on Amsterdam’s IJburg harbor. It comprises 273 units, with 190 mid-market rental studios and 83 owner-occupied apartments. Aside from the residential units, the project concept offers extensive communal areas and comprehensive, state-of-the-art facilities that are intended to accommodate not only Jonas’ residents but also people living in neighboring communities. One can say that Jonas has been realized as IJburg’s living room.

The physical appearance of the project is its initial distinguishing feature. Behind the glass façade, the architect conceals a variety of architectural gimmicks, such as the layout’s features, which are supposed to have slightly deviated corners and shapes that resemble a diamond shape. The pre-patinated zinc material of the façade gives the building a fresh look and feel. Parts of the structure are carved out to reveal the heart of the spatial program: a courtyard that expands and runs through the complex.

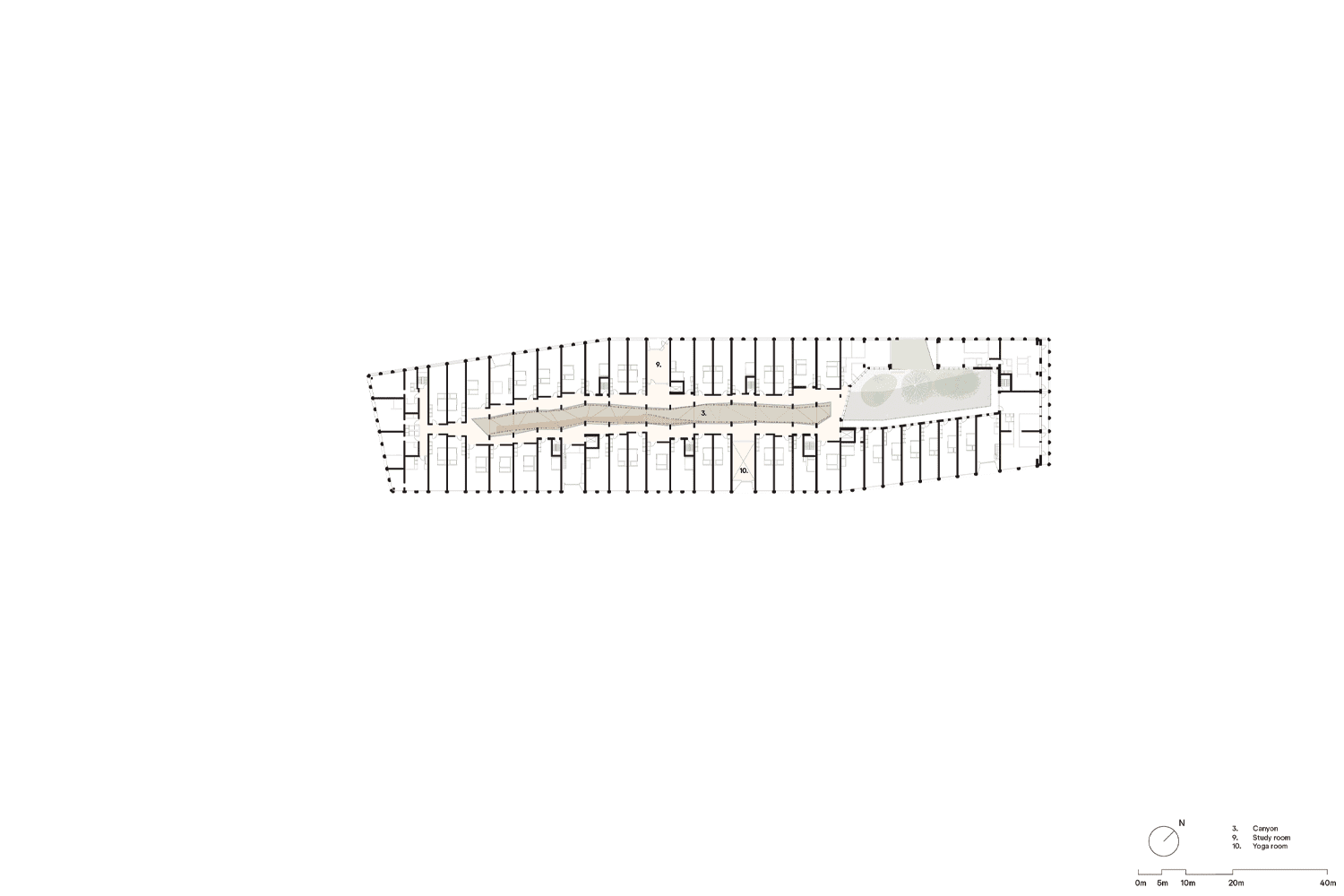

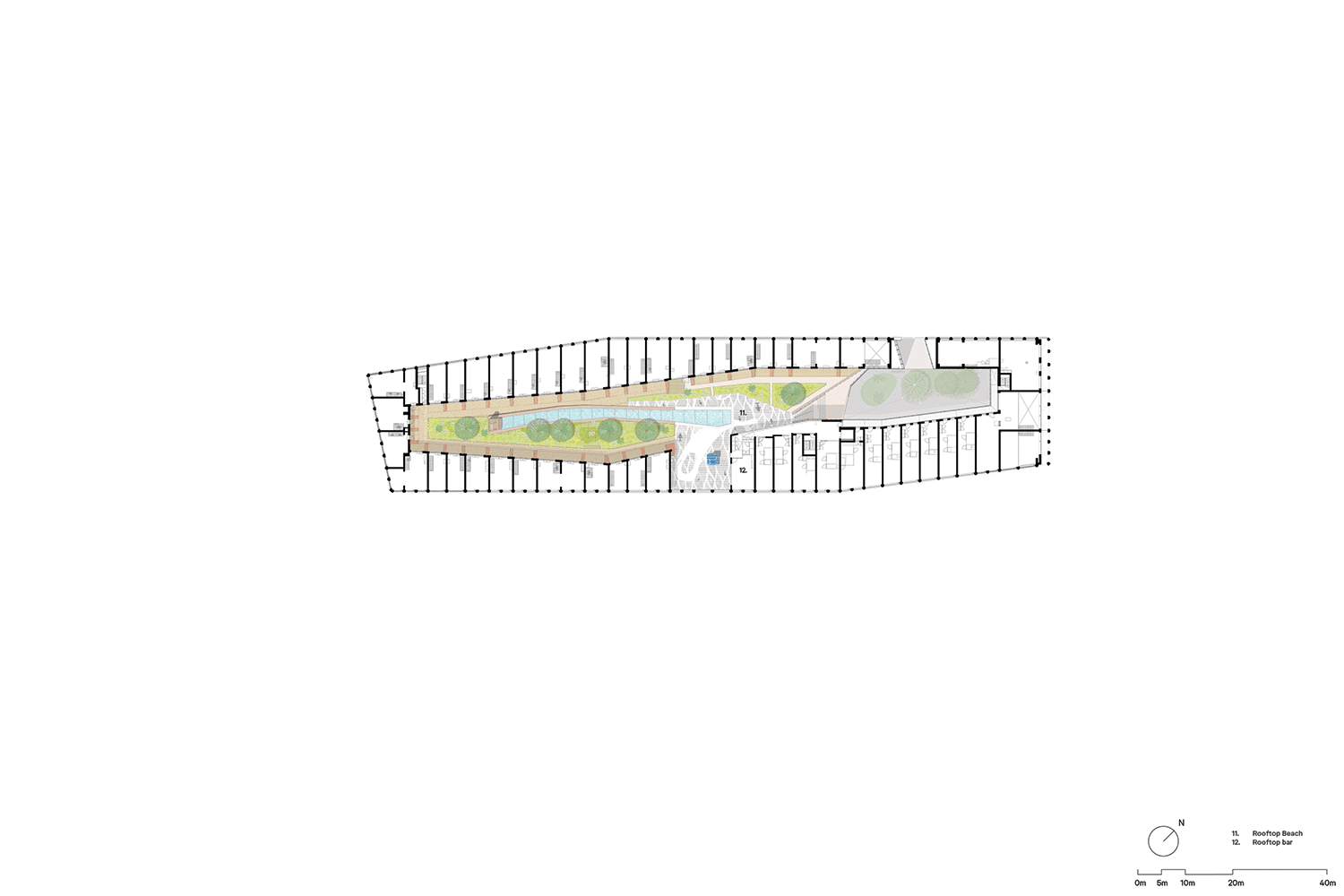

While the outside appearance is designed to contain contorted and angled corners and surfaces, the inner courtyard reveals more intricate corners and contours. The landscape of the communal route and courtyard is referred to as the ‘Canyon,’ alluding to the taper and depth of the softly undulating wooden surface of the inner part of the façade. The use of wood in the courtyard’s interior produces more whimsical and fascinating spatial experiences that contrast with the simple appearance of the outside. Aside from its physical appearance, the courtyard is designed to function as a shared space with a series of routes that are open for public access, allowing other residents living on the IJburg islands to use the public and collective program, which includes the living room, cinema, mountain path, forest patio, rooftop beach, and bars that exist as parts of the canyon. The space is linked to a series of slopes that lead up to other communal areas on the upper floors, such as the yoga room, study room, and outdoor rooftop garden, all of which are part of the project’s intention to serve as a gathering place for people living in the surrounding communities to participate in a variety of activities.

Since its inception, the project has drawn significant criticism, particularly from the environmental movement, which contends that IJburg’s sizable man-made creation is an invasion of nature at a time when the world is facing climate change and environmental crises. It’s become predictable how residential development projects in recent years have prioritized sustainable living, and Jonas is no exception. The project emphasizes a residential community approach and architectural design that is not only built with the utmost respect for the existing environmental surroundings but also incorporates these features as a major selling point.

The project’s environmental considerations and attention have resulted in the design of a building that not only minimizes the negative effects of human living on the environment but also has a number of functional components that help foster and improve the surrounding ecosystem. One example is how the design of the rooftop garden is home to trees and plants that can slow down the water stream while it rains to allow the water to be stored in the underground rainwater collection and storage system, which is built for water to be reused within the project. Furthermore, the design takes into account the presence of indigenous plants and large trees to increase the green space ratio and shade areas within the landscape. It also includes other environmental components such as mussel reefs, which have been placed around the islands to stimulate underwater life, or the specially built nesting walls for indigenous sand martins, a species of indigenous bird whose numbers have decreased due to urban expansion.

All of these factors are meant to help revitalize and restore the balance of the area’s ecosystem. All we can do now is wait to see if these initiatives are simply part of the project’s advertising strategy or if they will be feasible in the long run. What is apparent, however, is how the emphasis on human connection, community, social, and environmental responsibility has become crucial and inevitable requirements that developers, architects, and designers must factor in and work with, in addition to a work’s functions and appealing visuals.

_

1 IN SEARCH OF THE RATIONAL CITY by Anna Mielnik, Back to the Sense of the City: 11th VCT International monograph, 2016, July, Krakow, 117 – 128.