THE STUDIO WAS ORIGINALLY A GARDEN WHERE ONLY HUMAN BUILT THEIR SMALL WORKSPACE AND EVOLVED INTO A FULL-FLEDGED STUDIO WHICH BECAME A SIGNIFICANT REFERENCE FOR CLIENTS

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

In 2018, just as they were poised to graduate from the Faculty of Architecture and Design at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, architects Runn Charksmithanont and Chayaluck Peechapat—the founders of Only Human—found themselves with three project commissions arriving simultaneously. One was the strikingly dramatic Sohelou St. Marc Catholic Chapel in Tak province. Around the same time, they undertook the construction of the Only Human Studio in their own backyard—a project that would soon become a significant reference point. Clients who visit to discuss projects often express a desire for something similar for themselves.

“This place was originally just a garden where we built a small workspace with a rooftop deck to sit and enjoy the breeze,” Runn recalls the studio’s origins. Initially constructed during their thesis period, the modest garden workspace evolved into a full-fledged studio as projects began to flow in earnestly. “We didn’t even drive piles for the foundation because we started with just a single floor and a rooftop made of steel frames at varying levels for casual seating.”

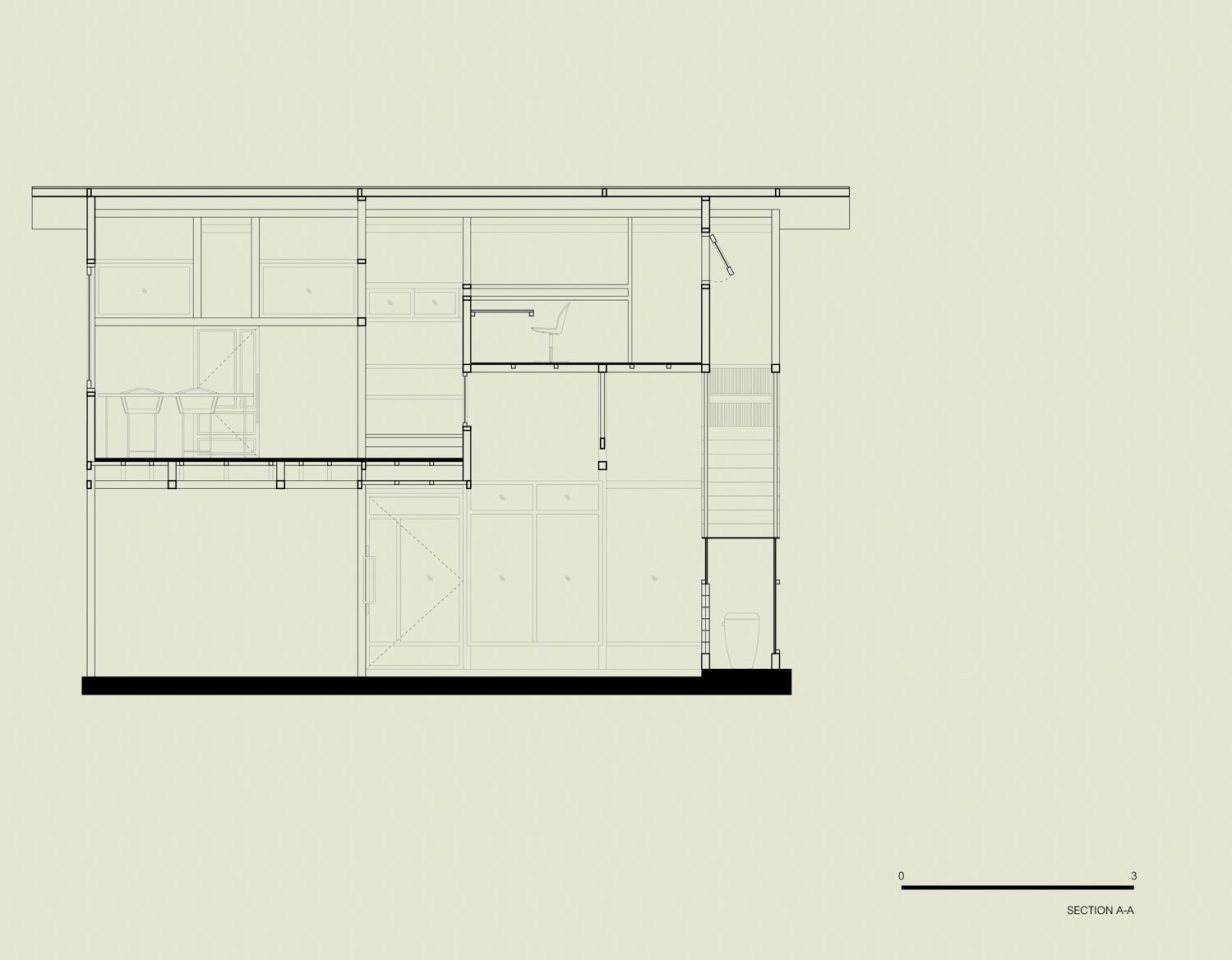

Since the building’s foundation remained a simple spread footing with the structure built directly upon it, the duo told art4d that their primary structural materials were merely 4×4-inch and 2×2-inch steel box tubes. To keep the structure as light as possible, they clad all the walls with cement boards. The ceiling was finished with affordable rubber plywood. Their use of color was straightforward: they chose a shade of gray matching the steel primer to help the building blend seamlessly with the garden. Inside, they painted the walls green to connect with the surrounding foliage, incorporating touches of orange in certain areas to bridge the hues between the plywood and the green.

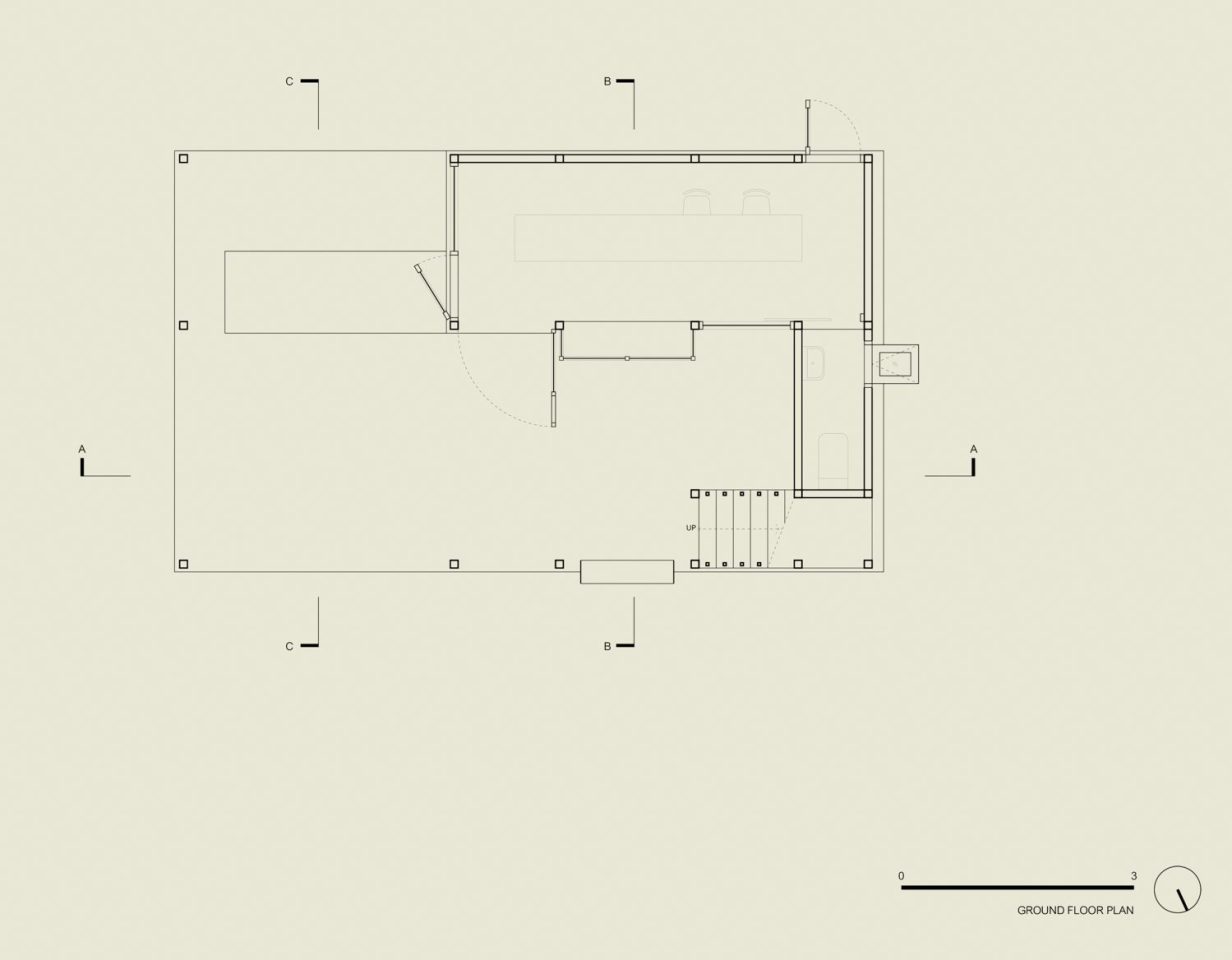

“Throughout the entire project, we had only one steelworker, one builder, and the two of us. We didn’t even have architectural drawings of the building,” recall the two founders. Their two-story studio, encompassing approximately 120 square meters of usable space, gradually materialized through their daily on-site efforts. Designing the building around the negative spaces of the existing garden and trees—determined not to fell any—they allowed nature to dictate the structure’s form.

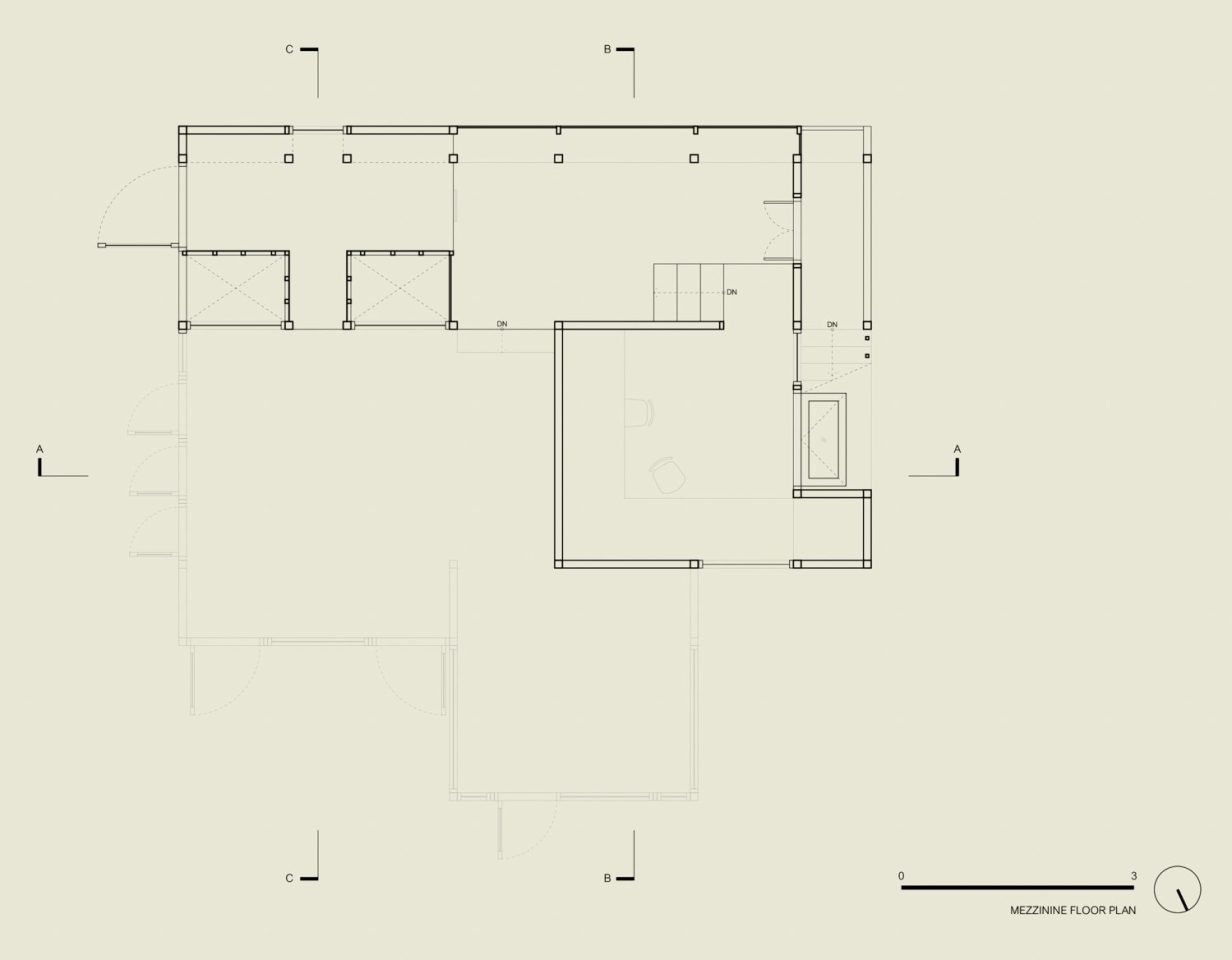

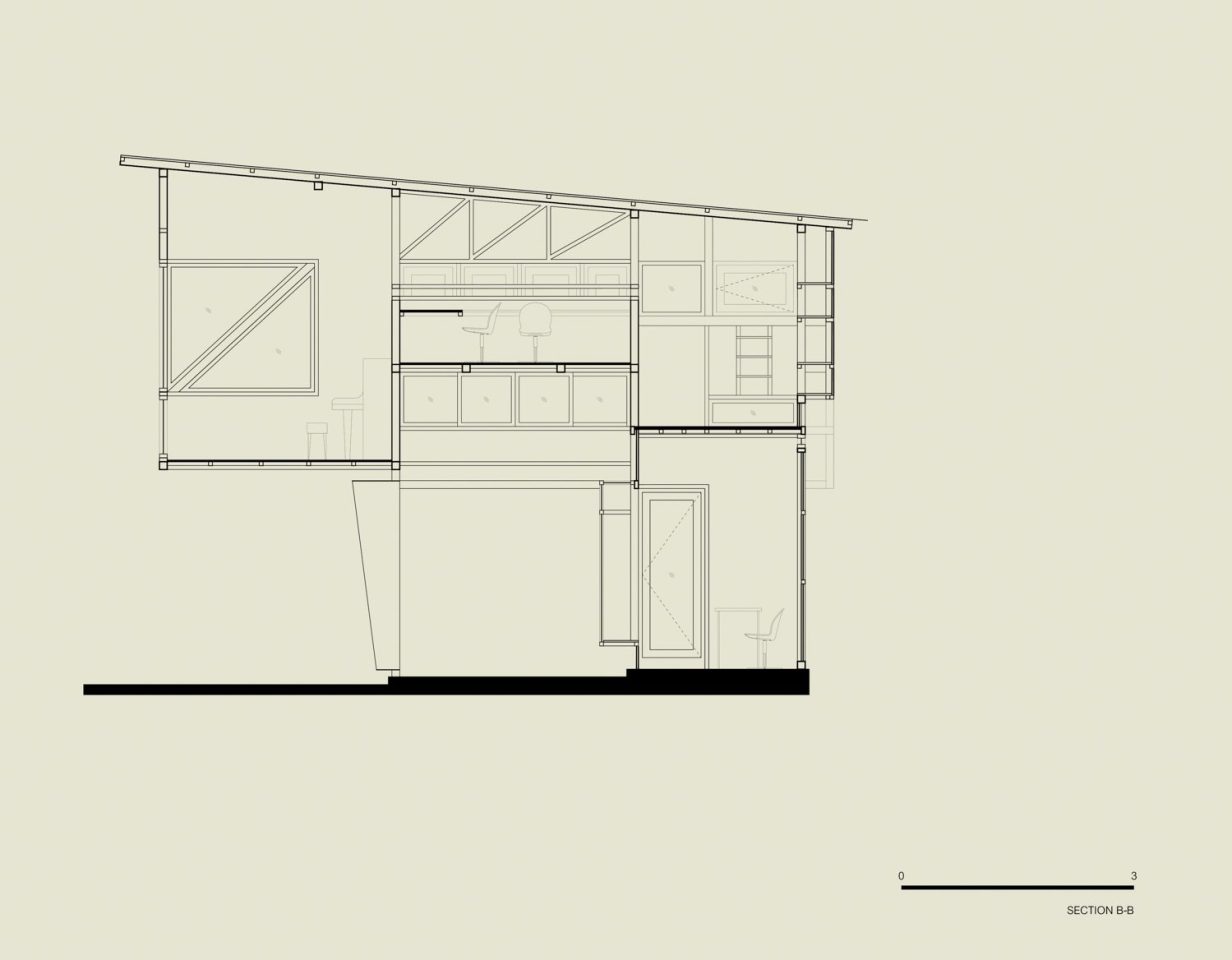

“That protruding mass you see at the front came about because we wanted to expand the upper floor’s space. So we stood below, gazing up at the sky to identify where we could expand without disturbing the trees.” Runn explains the genesis of the more-than-three-meter front extension. Chayaluck adds, “All these steel frames you see aren’t decorative; they serve a purpose” pointing to the building’s structure, where box steel bars are melded diagonally to form trusses to reinforce the cantilevered section. “We intended to showcase the structural elements as part of the building’s aesthetic.”

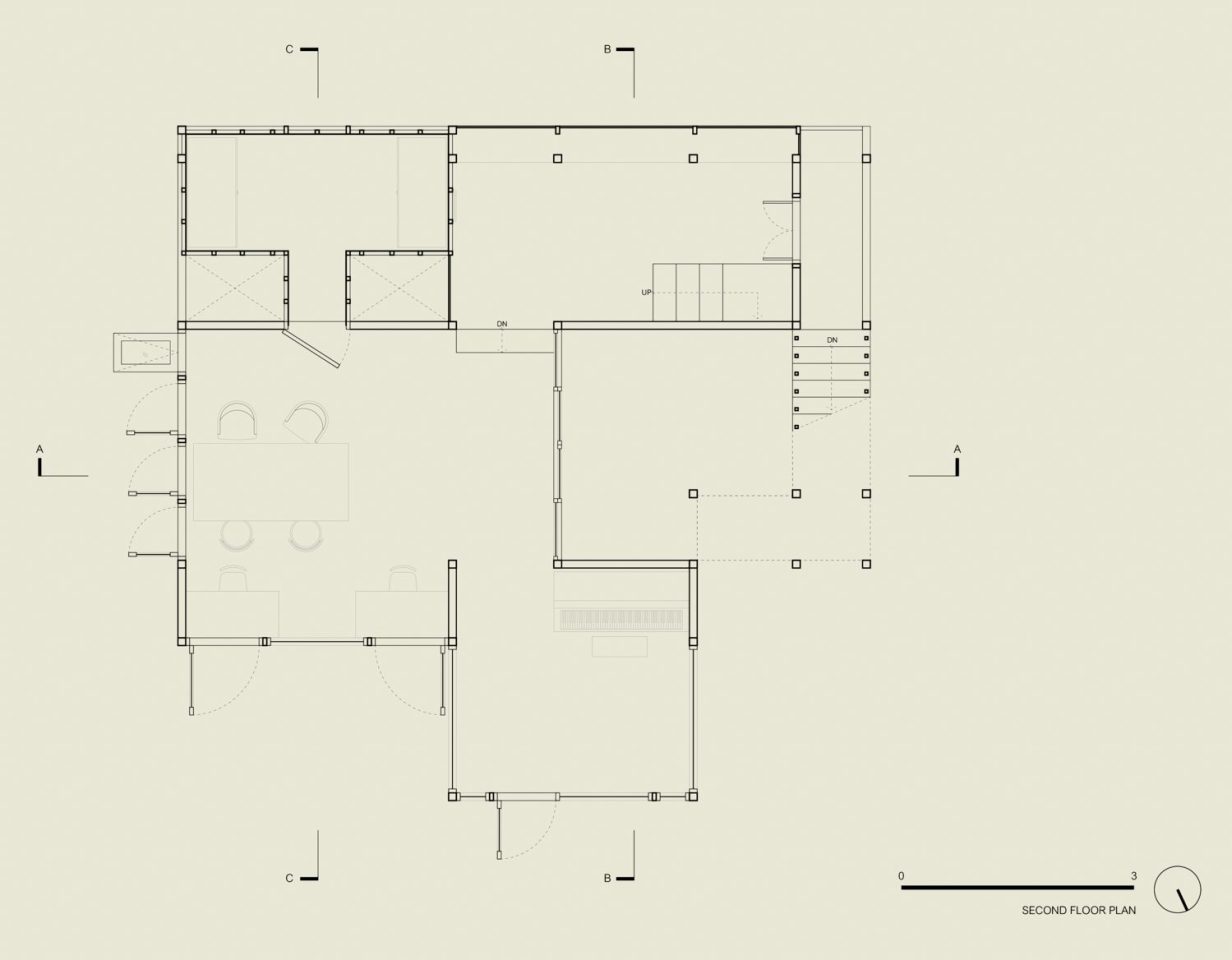

The functional spaces are thoughtfully arranged. Accessed via an external staircase, the main workspace occupies the second floor (the ground floor serves as a private office for illustration work). The area is divided into staff workstations and a meeting table, a lounge area (the cantilevered portion of the building) a small storage room accessed by stepping down a single stair, with a model display shelf built into the upper section (originally envisioned as a ‘Doraemon-style’ sleeping nook), and the founders’ workspace (distinguished by the orange paint), which requires ascending four additional steps. These varying levels mirror the original stepped design of the old rooftop, adding intrigue and transforming the space from a conventional flat, two-story studio into one that embraces volumetric dynamics, capitalizing on differing ceiling heights throughout.

Another intriguing detail is how some of the work desks, bookshelves, and nearly all the model display shelves were integrated into the building’s structure from the very beginning. “They’re essentially structural built-in furniture. What you see as bookshelves are actually the building’s columns—we just welded steel beams and placed tops on them,” Chayaluck elaborates, explaining the building’s nuances. “If you zoom in on the edges of the box steel frames where they connect with the cement board panels, you’ll notice wall trims made from angle steel. Actually, they’re not even traditional trims; we adapted angle steel to tidy up the joints between the box steel frames and the cement boards.” This approach ultimately became a crucial element that ensured the neatness and continuity of materials both inside and outside the building.

“For me, what’s important about this building is the structure, the choice of materials, the use of color, and the openings where we’ve tried to maintain the feeling of being on a rooftop. We aimed to ensure that even without air conditioning—just by opening the windows—you’d still get the same breeze as when you’re on the rooftop,” Runn notes.

It’s fair to say they built Only Human Studio at just the right moment. This project afforded both architects the opportunity to experiment freely and authentically. Working on-site with steelworkers allowed them to understand the limits of steel, welding techniques, and cutting methods—knowledge they applied when working on the Sohelou St. Marc Catholic Chapel in Tak province. The end result carries a certain resonance between the two works. “Clients often say they want something like our studio. Our current challenge, at the moment, is figuring out how to make each project different while still retaining some of that essence,” they explain. However, the duo emphasizes to art4d that what Only Human truly strives for in every project is to design in the most straightforward and minimal way possible.