THE EPILOGUE OF THE STUDY OF FRONT PALACE (WANG NA) WHERE CURATORIAL TEAM LED BY NATHALIE BOUTIN, SIRIKITIYA JENSEN AND MARY PANSANGA UTILISES THE ISSARA WINITCHAI THRONE HALL, NATIONAL MUSEUM, AS A CONTEMPORARY ART SPACE

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For English, please scroll down)

ไม่ไกลจากนิทรรศการ นัยระนาบนอก อินซิทู : แปลงร่างอดีตในหลืบแห่งปัจจุบัน ที่จัดขึ้นในพระที่นั่งอิศราวินิจฉัย พิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ ในมหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร วังท่าพระ (ที่กำลังดำเนินการปรับปรุงครั้งใหญ่) คนงานเจอเข้ากับฐานรากของสิ่งปลูกสร้างบางอย่างใกล้ๆ กับท้องพระโรงวังท่าพระ การขุดค้นครั้งนี้ดึงอะไรบางอย่างกลับมายังปัจจุบันมากกว่าภาพที่ตาเห็นแค่แนวอิฐเก่าและแอ่งน้ำขัง แต่พ่วงเอาประวัติศาสตร์ของวังท่าพระและความเป็นมาของเก๋งจีนที่พังทลายลงในรัชสมัยของรัชกาลที่ 5 กลับเข้ามาอยู่ในความรับรู้อีกครั้งด้วย ถึงแม้จะมองด้วยตาเปล่าไม่เห็นแต่ประวัติศาสตร์ไม่ได้หายไปไหน มันอยู่ตรงนั้นรอโอกาสที่จะถูกค้นพบ เช่นเดียวกันกับเรื่องราวของพระราชวังบวรสถานมงคล หรือที่คุ้นหูกันในชื่อ “วังหน้า”

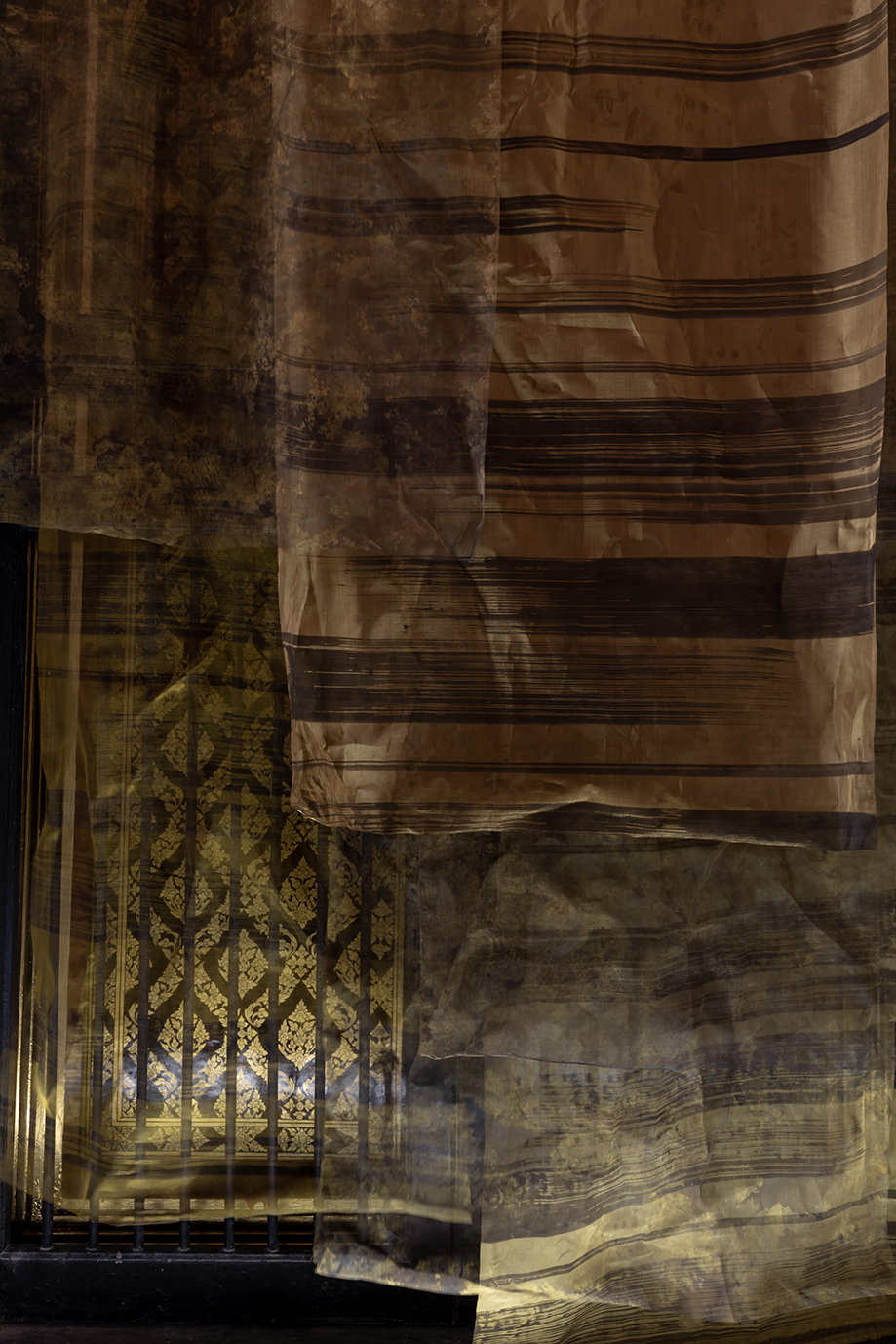

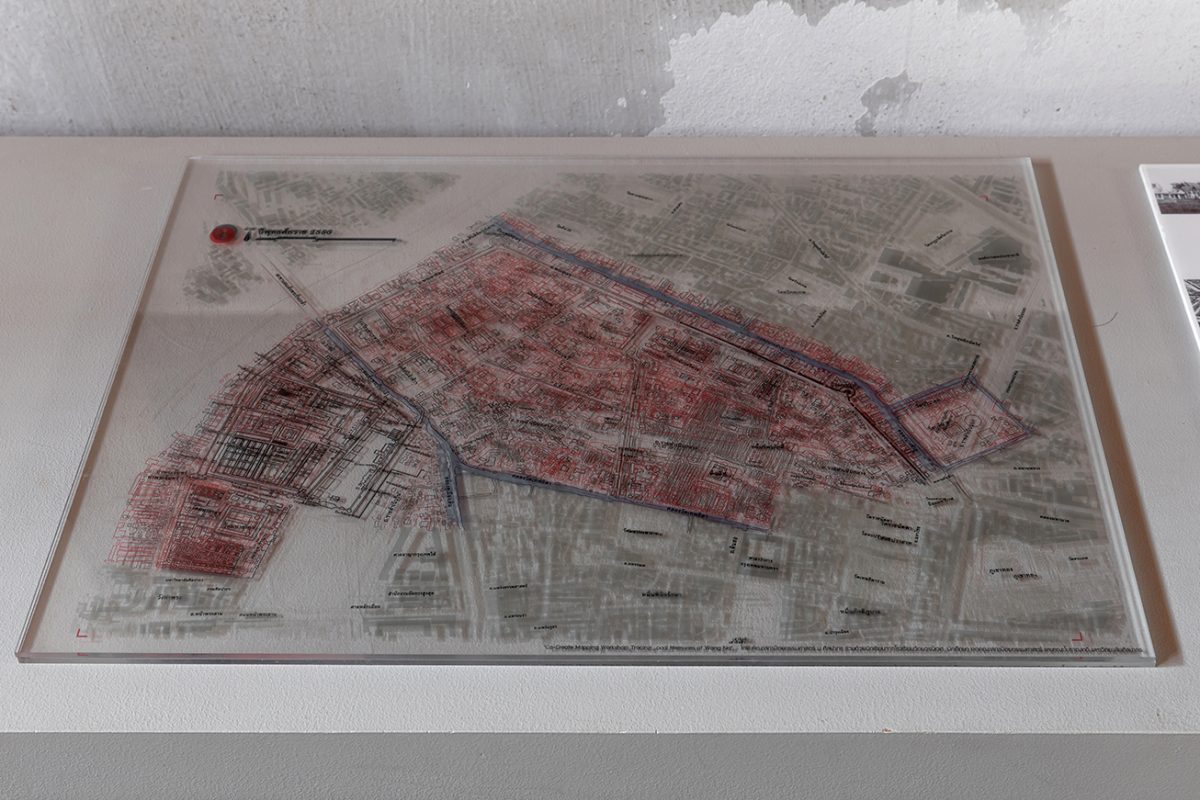

ในกรณีของวังหน้านั้นต่างออกไป วาระที่อดีตกลับมายังปัจจุบันไม่ใช่การขุดเชิงกายภาพ แต่เป็น “การจัดนิทรรศการ” ซึ่งด้วยจำนวน collaborator ที่มาร่วมงานครั้งนี้กว่า 20 คน จากหลากสาขาวิชาชีพนั้นก็ทำให้เรื่องราวในอดีตเกี่ยวกับวังหน้ากลับมายังปัจจุบันเป็นจำนวนมหาศาล กลุ่มนักภาษาศาสตร์ นำพระนามของสมเด็จพระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว และสมเด็จพระปิ่นเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว มาถอดองค์ประกอบเพื่อชี้ให้เห็นถึงคติการตั้งพระปรมาภิไธยที่เพิ่งเกิดขึ้นในรัชสมัยนั้น จารุพัชร อาชวะสมิต จำลองผ้าม่านกั้นพื้นที่ระหว่างมุกกระสันและท้องพระโรงด้วยเทคนิคการทอสมัยใหม่ สุวิชชา ดุษฎีวนิช รับหน้าที่ออกแบบม้านั่งในมุขกระสัน (ที่นั่งสบายอย่างไม่น่าเชื่อ) สำหรับให้ผู้ชมได้มีที่นั่งอ่านเอกสารต่างๆ ของนิทรรศการ ตุล ไวฑูรเกียรติ จากวงอพาร์ตเมนต์คุณป้า และ The Marmosets แต่งเพลง The Ghosts of Wang Na โดยนำบทเพลงยาวพระราชนิพนธ์ของสมเด็จพระปิ่นเกล้ามาอ่านประกอบเพลงอิเล็คทรอนิกส์ ชุดารี เทพาคำ เชฟที่ใช้อาหารเป็นสื่อสะท้อนประวัติศาสตร์ จัด Chef’s Table รับรองแขก (VIP) เติมเต็มให้นิทรรศการครั้งนี้นำเสนอเรื่องราวของวังหน้าได้ครบสัมผัส 5 รูป รส กลิ่น เสียง สัมผัส รวมไปถึง สุพิชชา โตวิวิชญ์ และ ชาตรี ประกิตนนทการ ที่ทำเวิร์คช็อปกับนักเรียนนักศึกษาลงสำรวจพื้นที่รอบๆ วังหน้าในปัจจุบันและเสร็จออกมาเป็นแผนที่กรุงเทพฯ สองแผ่น

แผนที่อะคริลิคแผ่นแรก (หมึกสีดำ) คัดมาจากแผนที่กรุงเทพฯ ปี พ.ศ. 2430 ซึ่งน่าจะเป็นแผนที่เพียงฉบับเดียวที่ทำให้เห็น อาณาเขตและตำแหน่งของอาคารต่างๆ ในวังหน้า กลับกัน แผนที่แผ่นที่สอง (หมึกสีแดง) แผนที่วังหน้าและพื้นที่โดยรอบในปัจจุบันทำให้เห็นการหายไปของสิ่งเหล่านั้น การปรากฏขึ้นของถนนราชดำเนินและการหายไปของวัดปรินายกซึ่งเป็นวัดของขุนนางชั้นผู้ใหญ่ช่วงต้นกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์ ทำให้ขอบเขตเรื่องราวของนิทรรศการนี้กินความไปมากกว่าประวัติศาสตร์ช่วงรัชกาลที่ 4 แต่เกินเลยไปถึงความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างวังหลวงและวังหน้าในช่วงรัชสมัยของรัชกาลที่ 5 ที่ย่ำแย่จนนำไปสู่การยกเลิกตำแหน่งวังหน้า ในปี พ.ศ. 2428 และการเริ่มต้นของระบอบสมบูรณาญาสิทธิราชย์

แผนที่สองแผ่นที่กล่าวถึงข้างต้นบ่งบอกถึงธรรมชาติของการนำเสนอประวัติศาสตร์และความจริงที่ว่าไม่มีใครสามารถควบคุม “ขอบเขต” ของเรื่องราวที่ไหลบ่ากลับมาในปัจจุบัน ขอบเขตที่ว่านี้ยังถูกขยายออกไปอีกขั้นผ่านงานศิลปะร่วมสมัยจากศิลปิน 7 คน อย่าง ธนัชชัย บรรดาศักดิ์, On Kawara, อุดมศักดิ์ กฤษณมิษ, นิพันธ์ โอฬารนิเวศน์, ปรัชญา พิณทอง, ฤกษ์ฤทธิ์ ตีระวนิช และ Danh Vō ที่ทีมคิวเรเตอร์ประกอบด้วย Nathalie Boutin สิริกิติยา เจนเซน และแมรี่ ปานสง่า มอบหมายให้ทำงานศิลปะกับพื้นที่ท้องพระโรงพระที่นั่งอิศราวินิจฉัย

ศิลปะร่วมสมัยคือคนแปลกหน้าที่ไม่เคยปรากฏให้เห็นในท้องพระโรง อุดมศักดิ์ กษฤณนิษ ไม่ถึงกับเปลี่ยนท้องพระโรงให้กลายเป็นโบสถ์คริสต์ด้วยงาน Fourteen, 2019 ที่เขาเอาไปแปะผนังข้างช่องหน้าต่างของพระที่นั่งอิศราวินิจฉัยในตำแหน่งคล้ายๆ กับการติดภาพมรรคาศักดิ์สิทธิ์ แต่ก็ทำให้ผู้ชมกลุ่มใหญ่ทีเดียวถามว่า ผลงานเศษกระดาษที่มีรอยเปื้อนสีเหล่านั้นคืองานศิลปะจริงๆ หรือ? (คำาถามไม่ต่างไปจากในหอศิลป์เลยทีเดียว) ปรัชญา พิณทอง กำหนดคีย์เวิร์ดและมอบหมายให้ทีมงานที่จะเดินๆ อยู่บริเวณพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ กระซิบคีย์เวิร์ดส่งต่อให้ผู้เข้าชม (บางคน) นำไปบอกต่อที่ห้องขายตั๋วเพื่อจะได้เข้าชมพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติโดยไม่เสียค่าใช้จ่าย กายภาพของผลงานนี้เป็นแท่งไม้เล็กๆ ติดอยู่กับผนังเสา บนนั้นเป็นกระดาษเคมีที่ถอดมาจากเครื่องนับจำนวนซึ่งจะทำหน้าที่เป็นหลักฐานการเกิดขึ้นของเหตุการณ์ (หรือประวัติศาสตร์) เป็นนามนัยของการส่งต่อเรื่องเล่าจากปากสู่ปากที่เพิ่มจำนวนขึ้นตลอดระยะเวลาของนิทรรศการ

ในขณะที่ unlock, 2019 ของปรัชญา พิณทอง “แทรกแซง” ระบบของพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ ด้วยการเปิดโอกาสให้คนเข้าสู่พิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติฟรีๆ ในนามของศิลปะร่วมสมัย และในนามของศิลปินศิลปะร่วมสมัย นิพันธ์ โอฬารนิเวศน์ ก็นำศิลปะวัตถุของพิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติมาเป็นงานศิลปะ ศิลปินนำลูกแก้วปรอท (ที่จำลองขึ้นมา) ไปจัดแสดงในพระที่นั่งอิศเรศราชานุสรณ์ และย้ายลูกแก้วปรอท (Mercury Ball) มาตั้งไว้ในท้องพระโรง เยื้องๆ กับ ห่วงโลหะสองวงที่สลักเนื้อเพลงลาวแพน ในสองภาษา – ไทยและลาว

นิพันธ์พูดถึงประเด็นการผลัดถิ่น พรมแดนสมมติ และความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างมนุษย์และพื้นที่ในงานศิลปะของเขามาอย่างต่อเนื่อง กับผลงาน เรือนร่างของสิ่งที่ไม่มีอยู่นั้นเป็นรูปทรงกลม, 2019 ศิลปินย้อนกลับไปพูดถึงกลุ่มคนลาวพลัดถิ่นในกรุงเทพฯ ช่วงต้นกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์ผ่านเพลงลาวแพน เอกสารประกอบนิทรรศการในห้องมุกกะสัน และลูกแก้วปรอทซึ่งทำงานร่วมกันได้อย่างน่าสนใจ เนื้อความในเอกสาร คือพระราชโองการของพระบาทสมเด็จพระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว ห้ามไม่ให้มีการเล่น “แอ่วลาว” หรือ “ลาวแคน” ที่แพร่กระจายเข้ามาในสยามพร้อมๆ กับกลุ่มคนชนชาติลาว ที่ถูกกวาดต้อนเข้ามายังพระนครภายหลังจากสงครามกบฏเจ้าอนุวงศ์ เพราะทรงมองว่าจะเป็นภัยต่อการดำรงอยู่ของการละเล่นดั้งเดิมของคนสยาม นอกจากนั้นเอกสารดังกล่าวยังระบุถึงรสนิยมของ พระบาทสมเด็จพระปิ่นเกล้าที่ทรงชื่นชอบและเชี่ยวชาญการเป่าแคนลาวเป็นพิเศษอย่างชัดเจน

ศิลปินบอกกับ art4d ว่า “ตรงตำแหน่งเดิมของลูกแก้วปรอทในพระที่นั่งอิศเรศราชานุสรณ์ ถ้ามองเข้าไปในลูกแก้วจะเห็น บทนิพนธ์เพลงแอ่วลาวของพระบาทสมเด็จพระปิ่นเกล้า และแคน ในคราวเดียวกัน” ตำแหน่งเดียวกันนี้ถูกจำลองมาอยู่ในท้องพระโรงผ่านการจัดวางลูกแก้วปรอทกับห่วงโลหะให้อยู่เยื้องๆ กัน ซึ่งเมื่อมองเข้าไปเราจะเห็นห่วงโลหะสลักเพลงลาวแพน 2 ห่วง และบุษบกมาลา พระราชบัลลังก์ที่ประทับของกรมพระราชวังบวรฯ อยู่ที่ปลายตา เนื้อเพลงที่สลักอยู่บนขอบด้านในของห่วงโลหะ คือลาวแพนฉบับดั้งเดิมที่เล่าถึงความลำบากยากแค้นในการใช้ชีวิตในพระนคร การโดนกดขี่โดย “พี่สยาม” และความคับแค้นใจที่ต้องพลัดพรากจากบ้านเกิด จบบทด้วย “เป็นกรรมของเราเพราะเจ้าเวียงจันทน์ อ้ายเพื่อนเอ๋ย”

เนื้อหาที่ค่อนไปทางการปลุกระดมต่อต้านนี้เองคงจะเป็นอีกเหตุผลที่ ร.4 มีพระราชโองการออกมาในลักษณะนั้น อย่างไรก็ตามการปรากฏขึ้นของลาวแพนเวอร์ชั่นดั้งเดิมไม่ได้ช่วยให้เห็นบริบทของการเมืองในช่วงนั้นเพียงอย่างเดียว เพราะสิ่งที่ปรากฏ ทำให้สิ่งที่ไม่ปรากฏในห้องนิทรรศการเผยตัวออกมาเช่นกัน นั่นคือ เพลงลาวแพนเวอร์ชั่นอื่นๆ ที่ความหมายของเพลงค่อยๆ ผันผวนไปตามเวลาในลาวแพนใหญ่ จากบทละครร้องเรื่องพระลอของ กรมพระนราธิปประพันธ์พงศ์ ใจความของเพลงถูกเปลี่ยนให้กลายเป็นการตัดพ้อเรื่องรักๆ ใคร่ๆ ไปเสียอย่างนั้น หรือ ลาวแพน ฉบับหลวงวิจิตรวาทการ ในยุคจอมพล ป. พิบูลสงคราม ที่ไม่เหลือเนื้อความของการทนทุกข์จากการต้องพลัดถิ่นฐานในเพลงเลยแม้แต่น้อย เพราะความหมายของมันถูกฉุดกระชากไปรับใช้ชาติ ปลุกจิตสำนึกความเป็นชาติเดียวกัน ในยุคที่ฝรั่งเศสกำลังเข้ามามีอำนาจในฝั่งซ้ายของแม่น้ำโขง

จะว่าไปการทำงานกับประวัติศาสตร์ของศิลปินในครั้งนี้ ก็คงคล้ายๆ กับมือของคนสวนที่บรรจงกำคัดเตอร์กรีดวัชพืช ////////, 2019 โดย ธณัฐชัย บรรดาศักดิ์ ในตอนการถ่ายทำ จริงอยู่ว่ามือดังกล่าวกำลังกรีดวัชพืชออกจากขอบกระเบื้องบริเวณพื้นที่ภายนอกของวังหน้า แต่ระหว่างเกือบๆ 2 เดือนของนิทรรศการนั้น ปลายคัตเตอร์อันเดียวกันนั้นกำลังกรีดลงไปบนผิวชั้นนอกของเสาต้นหนึ่งของท้องพระโรง ตัดขวางลึกลงไปจนเห็นชั้นของเนื้อเยื่อภายใน เปิดให้เรื่องราวในอดีตเผยตัวออกมาอีกครั้งในปัจจุบันทีละนิดๆ นอกจากผลงานศิลปะและคนใส่เสื้อเหลืองที่คอยเฝ้าวัตถุศิลปะ ถ้าต้องตอบว่าเห็นอะไรอีกในท้องพระโรงละก็ เราคิดว่าเราเห็น “ความตึงเครียด” บางอย่างก่อตัวขึ้น เมื่อข้อมูลค่อยๆ ไหลกลับมาทีละนิดๆ ตามจังหวะที่ผลงานแต่ละชิ้นถูกอ่านโดยผู้ชม และเมื่อมันดูจะไม่ค่อยตรงกับประวัติศาสตร์ที่เคยเรียนตอนมัธยมฯ

นอกจากงานศิลปะอีก 4 ชิ้นที่ไม่ได้กล่าวถึง อีกจุดที่น่าจะต้อง “อ่าน” ในนิทรรศการคงจะเป็นชื่อ “นัยระนาบนอก” ที่ ดร. สายัณห์ แดงกลม ตั้งไว้ ได้ยินมาว่าชื่อนี้มีประเด็นติดตัวเรื่องความไม่กระจ่างมากพอให้อ่านครั้งเดียวแล้วเข้าใจ อันที่จริงชื่อที่คลุมเครือเปิดโอกาสให้อ่านได้หลายแบบมากกว่า ถ้าหากเว้นระยะและถอยออกมามองโครงสร้างของประโยคสักหน่อย จะเห็นว่าในนั้นมีทั้งการเล่นเสียงสัมผัส – นัย (ยะ) กับ ระ และสัมผัสพยัญชนะ – นาบ กับ นอก หรือในเชิงความหมายก็มีทั้ง “ใน” (นัย) และ “นอก” ในคำเดียวกัน เสียงสัมผัสช่วยร้อยคำให้เป็นเนื้อเดียวกัน แต่พร้อมๆ กันนั้นก็ชี้ว่าความจริงแล้วมันแยกออกจากกันได้ “นัย|ระนาบ|นอก” จึงบอกใบ้ถึงภาพลักษณ์ของคำว่าประวัติศาสตร์ที่ดูเหมือนจะเรียงกันเป็นเรื่องไร้รอยต่อ แต่ความจริงแล้วมันเต็มไปด้วย “หลืบ” ช่องว่างระหว่างเหตุการณ์จำนวนมาก อดีตในพระที่นั่งอิศราวินิจฉัยก็เช่นกันที่กลับมาในปัจจุบันแบบเป็นส่วนๆ ไม่ปะติดปะต่อ แสดงถึงความไม่เป็นเส้นตรง ไม่ใช่ของแข็งคงที่ตายตัวของประวัติศาสตร์ได้เป็นอย่างดี หน้าตาของประวัติศาสตร์จะเป็นอย่างไรนั้นขึ้นอยู่กับว่าจะอ่านจากมุมไหนส่วนความจริงที่ควรเก็บไว้ในใจก็คือประวัติศาสตร์สามารถปรับเปลี่ยนได้ตามความจำเป็นของผู้มีอำนาจ ไม่ต่างไปจากเนื้อเพลงลาวแพนที่เปลี่ยนไปตามบริบททางการเมือง

Not too far from the exhibition, In Situ from Outside: Reconfiguring the Past in Between the Present, which takes place inside Issara Winitchai Throne Hall of the National Museum, inside Wang Tha Pra Campus of Silpakorn University (which currently going through a major renovation), some of the workers discovered the foundation of some sort of built structure near the Throne Hall of Tha Pra Palace. The excavation brings something from the past back to the present, and in the sense that goes beyond what the eyes can see—the mass of an old brick wall and a flooded pool. It brings the history of Tha Pra Palace and the history of a Chinese pavilion demolished during the reign of King Rama V back into people’s awareness. Though invisible to the eyes, history never goes anywhere. It has always been there, waiting to be discovered, just like the story of Boworn Sathan Mongkol Mansion or the ‘Front Palace’ known as Wang Na.

Front Palace is, however, a different case. The past returns to the present in the form of, not a physical excavation, but an exhibition. With over 20 collaborators from various fields of study participating in the project, the history of Front Palace is brought back and blown up to such an immense scale. The linguists analyze the names of King Rama IV and Second King Pinklao in order to explore the layered nuances and significance of nomenclature in Thai culture.

Jarupatcha Achavasmit simulates the curtains that partitioned the audience hall and the corridor using a modern weaving technique. Suwicha Dussadeewanich takes the responsibility of designing a (surprisingly comfortable) bench, which is placed at the area of the corridor for viewers to sit on as they read the exhibition’s documents. Tul Waitoonkiat of the band Apartment Khunpa and The Marmosets co-wrote the song titled ‘The Ghosts of Wang Na,’ an electronic spin on a composition by King Pinklao. Tam Chudaree, a renowned chef known for her magnificent interpretation of history into culinary creations puts together a Chef’s Table for VIP guests, completing the story of Front Palace through the five physical senses (visual, taste, sound, touch and smell). Supitcha Tovivich and Chatri Prakitnonthakan team up for a workshop series that takes students to explore the area around the Front Palace today and created, as a result, are two maps of Bangkok.

The first one (printed in black ink) is derived from an 1887 edition of a map of the city. It is probably the only map that shows the perimeters and locations of buildings inside the Front Palace. The second map (printed in red ink) reveals the current setting of the Front Palace and its surrounding areas, depicting the changes and disappearance of things, from the existence of Ratchadamnoen Road to the absence of Parinayok Temple, which was the temple built specifically for the senior noblemen of the early Rattanakosin Era. The maps expand the content of the exhibition beyond the history during the time of King Rama 4, to the deteriorating relationship between the positions (Wang Na and Wang Luang) that led to the abolition of the Wang Na title in 1885 and the beginning of the absolute monarchy.

The two aforementioned maps reflects the nature of how history is presented and the fact that nobody can restrict the boundaries that prevent the past from pouring back into the present. Such boundaries are being taken to another level through the works of seven artists: Tanatchai Bandasak, On Kawara, Udomsak Krisanamis, Nipan Oranniwesna, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pratchaya Phinthong, and Danh Vō and under the brief from the curatorial team (Nathalie Boutin, Sirikitiya Jensen, Mary Pansanga), to create works within the spatial and historical context of Issara Winitchai Throne Hall.

Contemporary art is a stranger who has never been introduced to the Throne Hall before. While Udomsak Krisanamis doesn’t exactly transform the space of Throne Hall into a Christian Church with his ‘Fourteen’ (2019), in which he places a series of images around the exhibition space depicting the way that the fourteen Stations of the Cross or the Way of the Cross are placed around a church or a cathedral, his work does get a considerable number of viewers asking whether these pieces of paper with the seemingly stains of paint are actually works of art (the same question that is constantly asked by the audience at galleries). Pratchaya Phinthong specifies a bunch of keywords for the staff walking around the museum to whisper to some of the viewers, who will be able to watch the exhibition for free once they give the keywords to the ticket office. The physicality of his work can be found in the form of small wooden sticks attached on the columns with pieces of paper taken from the attendee counting machine. The work serves as evidence of the occurrence (or history), implying how the story has been transmitted from one person to another as the number of attendees continues to grow throughout the duration of the exhibition.

While Phinthong’s ‘unlock’ (2019) interferes with the system operated by the National Museum by letting people attend the show for free, in the name of Contemporary art and Contemporary art artist, Nipan Oranniwesna turns the museum’s permanent collection into a work of art. The artist reproduces the Mercury ball and replaces the original object which will be removed from Issares Rajanusorn Mansion to be displayed in the exhibition space, Issara Winitchai Throne Hall, slightly opposite to the two curved steel circles with engraved ‘Lao Phaen’ lyrics, in the Thai and Lao language.

Oranniwesna’s work has always discussed issues of displacement, imagined borders and relationships between humans and space. With his work ‘non-existent bodies are spherical’ (2019), the artist relates the lives of Laotian captives in Siam during the early Rattanakosin Era through the interesting union between the music of ‘Lao Phaen,’ a document displayed inside the Mukkrasan and the Mercury ball. The content in the document is actually King Rama IV’s official statement prohibiting the musical instrument and performance, Aew-Lao or Lao Khaen, brought to Siam by the Laotian diasporas who were forced to relocate to the capital city after Anouvong’s Rebellion. The King views its rising popularity as a threat to the Siamese people’s culture. The document also includes information about how Lao Khaen was a musical instrument that King Pinklao loved and was accomplished at playing.

“The Mercury ball’s original position inside Issares Rajanusorn Mansion allowed for one to look into the ball and see the musical instrument (Khaen) as well as the song ‘Aew-Lao,’ of which King Pinklao composed all at the same time.” This very same location is simulated and displayed inside the Throne Hall. The artist installed the Mercury ball and the steel circles to be slightly opposite to each other. Looking inside, one can see the steel circles with the engraved ‘Lao Phaen’ lyrics and the throne of the crowned prince out of the corner of one’s eyes. The engraved lyrics are the original lyrics of the song, which reflect the harsh life living in the capital city, the feeling of being suppressed by Siam and the indignation of being taken away from the motherland, with “my dear friend, we are suffering this karma because of the King of Vientiane.”

The lyrics that imply resistance were probably one of the reasons behind King Rama IV’s statement. Nevertheless, the existence of the original version of Lao Phaen not only provides the political context of Siam at the time but also reveals the things that are not included in the exhibition space – other different versions of Lao Phaen. The lyrics of the song have been altered over time. In the song ‘Lao Phaen Yai’ from the play, Phra Lor by Prince Narathip Prapanpong, the lyrics were somehow changed to be about unrequited love. During Field Marshall Plaek Piboonsongkram’s government, Luang Wichit Wathakarn’s version of ‘Lao Phaen’ spoke of nothing about the misery of diasporas. The meaning of the song was deviated to serve the nationalist agenda in the time when France was expanding its power on the left side of the Mekong River.

The artists’ interpretation of history for this exhibition is similar to the hands of a gardener meticulously cutting down the weeds in a garden in //////// (2019) by Tanatchai Bandasak. It is true that the film depicts the gardener’s hands as he purposely cuts the plant seedlings out from the gaps between concrete paving blocks, from one gap to another, but almost throughout the two-month period of the exhibition, the blade of the very same cutter was cutting the exterior surface of one of the Throne Hall’s columns. The sliced ground reveals various geological layers, allowing us to gradually explore past histories in today’s time. In addition to the works of art and the staff in yellow shirts guarding the exhibited objects, what we were able to observe from the space inside the throne hall is the ‘tension’ that was being formed. Information about the past finds its way back to the present as viewers read into the works exhibited in curated sequences, and start to notice that what they saw isn’t the same history they learned at school.

Apart from the remaining four works whose details are not included in the article, the Thai name of the exhibition given by Dr. Sayan Daengklom was also a topic of discussion, for most viewers were unable to immediately understand what it meant. Such obscurity allows for the exhibition to be read in much more diverse ways. If we were to break down the linguistic structure of the word ‘Naiya-ra-nab-nok,’ the rhymed ‘ya’/ ‘ra’ and ‘nab’/’nok’ as well as the meanings of ‘nai’ (inside) and ‘’nok’ (outside), we would be able to understand how this thoughtfully rhymed phrase can actually be separated. ‘Nai-ya-ra-nab-nok’ or ‘In Situ from Outside’ hints at the projected image of history as a seemingly seamless narrative, which is actually full of hidden folds; countless missing pieces in between incidents that have been left out. The past of inside Issara Winitchai Throne Hall, too, returns in fragments with the unconnected, non-linear, and changeable nature of history. The face of history depends on the aspect from which it is read while the unspoken reality is the fact that history is altered to serve those in power, just like how the lyrics of Lao Phaen were rewritten to suit the country’s ever-changing political contexts.