‘PEOPLE PLACE POIESIS’ IS AN EXHIBITION FEATURING WORKS BY MARINA TABASSUM THAT EXPLORES THE ROLE OF ARCHITECTURE AMIDST ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CRISES IN BANGLADESH

TEXT: XAROJ PHRAWONG

PHOTO: XAROJ PHRAWONG EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

An exhibition bringing together the work of Marina Tabassum, the Bangladeshi architect, is currently taking place at TOTO GALLERY·MA in Tokyo. Structured around three thematic lenses; People, Land, and Poiesis, the exhibition examines architectural practice within the context of Bangladesh, a country shaped by more than 700 rivers and vast deltaic landscapes, and perpetually exposed to flooding intensified by climate change. At its core, the exhibition poses a fundamental question: what form should architecture take amid such conditions? In a densely populated nation facing compounded environmental pressures, it further asks what role architects can meaningfully assume within society.

The exhibition unfolds in three parts. The first section, beginning on the third floor, presents works grounded in locality and projects developed for displaced communities. Upon entering this initial zone, visitors encounter a reconstruction of a rural Bangladeshi dwelling. The setting is evoked through a small mud-plastered courtyard, floors furnished with woven rope beds laid over straw mats, ceramic vessels, everyday household objects, and a traditional dugout boat carved from a single tree trunk. This opening section seeks to convey the rhythms of daily life in rural contexts, from which vernacular architectural forms emerge and take shape.

Photo: Nacasa & Partners

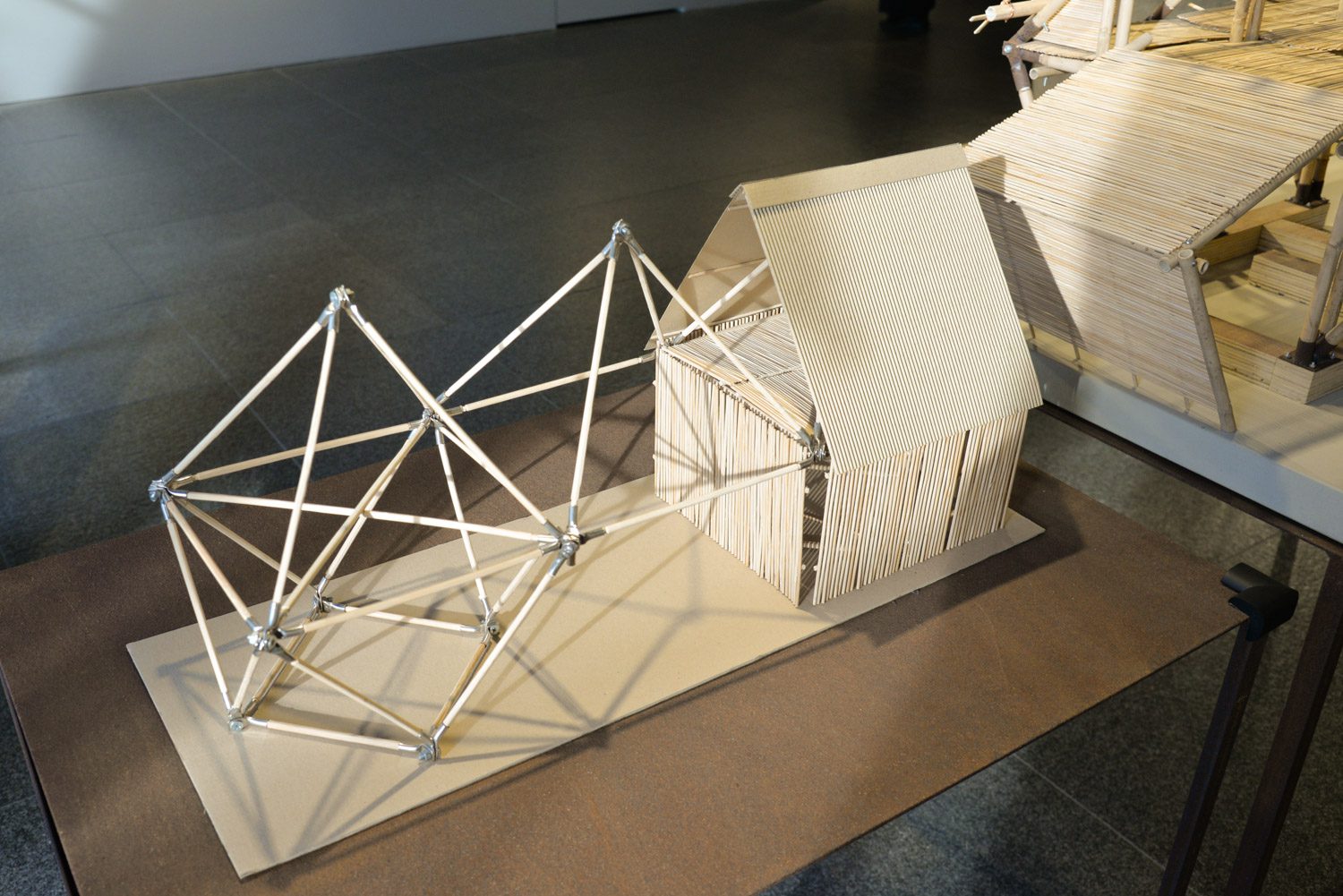

The architectural narrative begins with Aggregation Center, Teknaf, a project conceived as a refugee camp for the Rohingya, displaced by conflict in Myanmar. Constructed primarily from bamboo, an abundant and readily available material in Bangladesh, the building employs bamboo as its principal element, used both as a structural frame and as woven lattice walls. The camp is organized into a series of smaller building clusters, accommodating spaces for male and female gatherings as well as a community center. All structures within the camp are built using a consistent construction method: bamboo members assembled into frames and connected with steel joints. This system allows for rapid construction and dismantling, while remaining simple enough for Rohingya residents themselves to learn and participate in the building process. The technique is an evolution of the earlier Khudi Bari project, a lineage that is clearly communicated in the exhibition through enlarged-scale models, which make the construction process legible and accessible to visitors.

Khudi Bari, meaning ‘little house’ in the local language, is a mobile dwelling designed for people who have lost their homes. Conceived to be assembled and dismantled by community members within a short period of time, it also functions as a temporary shelter during floods. The house is raised on stilts, allowing the space beneath to be used during the day, while occupants sleep above at night and remain safely on the upper level when flooding occurs. The structure is composed of a bamboo frame system secured with steel joints specially designed for this project. Its construction is intentionally straightforward, enabling it to be built by local labor, while its dismantling and relocation can be carried out with equal efficiency. This adaptability has allowed Khudi Bari to be reproduced and deployed across multiple regions of Bangladesh, extending assistance to as many affected communities as possible.

The second section, staged outdoors, is particularly compelling. A full-scale ‘Khudi Bari,’ transported directly from Bangladesh, is installed on site, allowing visitors to grasp the project’s true scale and to closely observe how bamboo and steel joints work together through their construction details in a flood-resilient dwelling. The open courtyard is articulated by a series of river forms representing Bangladesh’s extensive waterways. These are rendered as maps fabricated from rusted steel plates, evoking the land itself; soil, brick, and the accumulated patina of time embedded in the country’s built environment. A notable highlight of this section is the presentation of a Japanese interpretation of Khudi Bari. Developed using Japanese materials and construction techniques, the project is realized through a collaboration with Kazuyoshi Morita, an architect deeply engaged with the Satoyama way of life in Kyoto, together with Morita Lab at Kyoto Prefectural University. The prototype takes the form of a small two-storey house structured around a frame system, replacing steel connectors with traditional Japanese rope-lashing joinery, while industrial roofing materials are substituted with bark shingles.

Photo: Nacasa & Partners

The third section, located on the fourth floor, turns to architectural practice within an urban context. Among the works presented is the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka. Beyond the drawings and photographs familiar from publications, the exhibition features a series of partial models that isolate and enlarge key architectural moments. These include brick-laying studies that reveal how circular and square geometries intersect, as well as variations of openings generated through the alternation of solid and porous brick walls.

Photo: Nacasa & Partners

A different approach is evident in the Alfadanga Mosque. While sharing the same religious program, the articulation of sacred light here differs through the scale and treatment of openings. Brick remains the primary material, but rather than alternating between solid and perforated masonry, space is defined by large, box-like brick volumes, each tilted at a 45-degree angle in differing orientations across the four façades, allowing light to enter and diffuse indirectly.

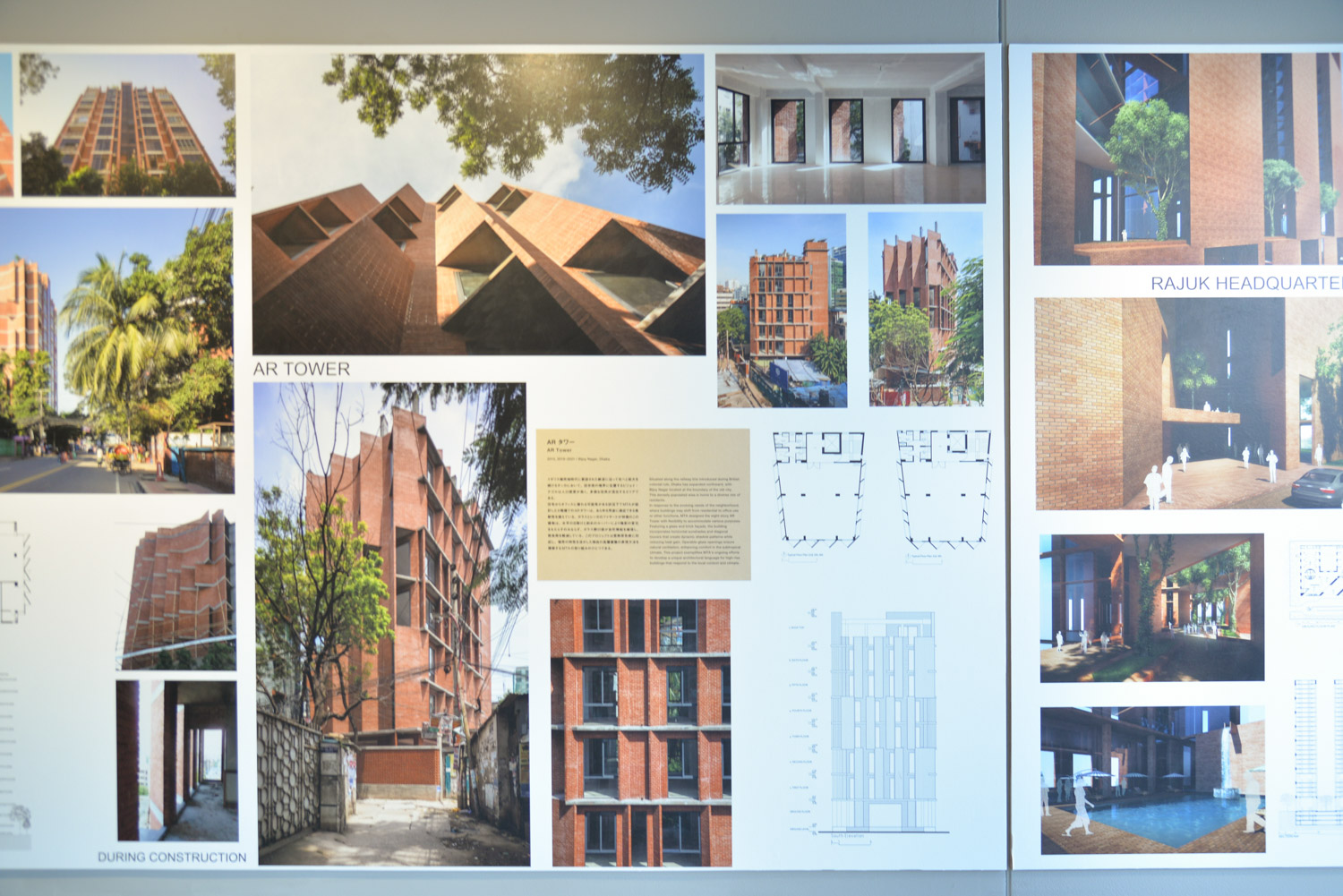

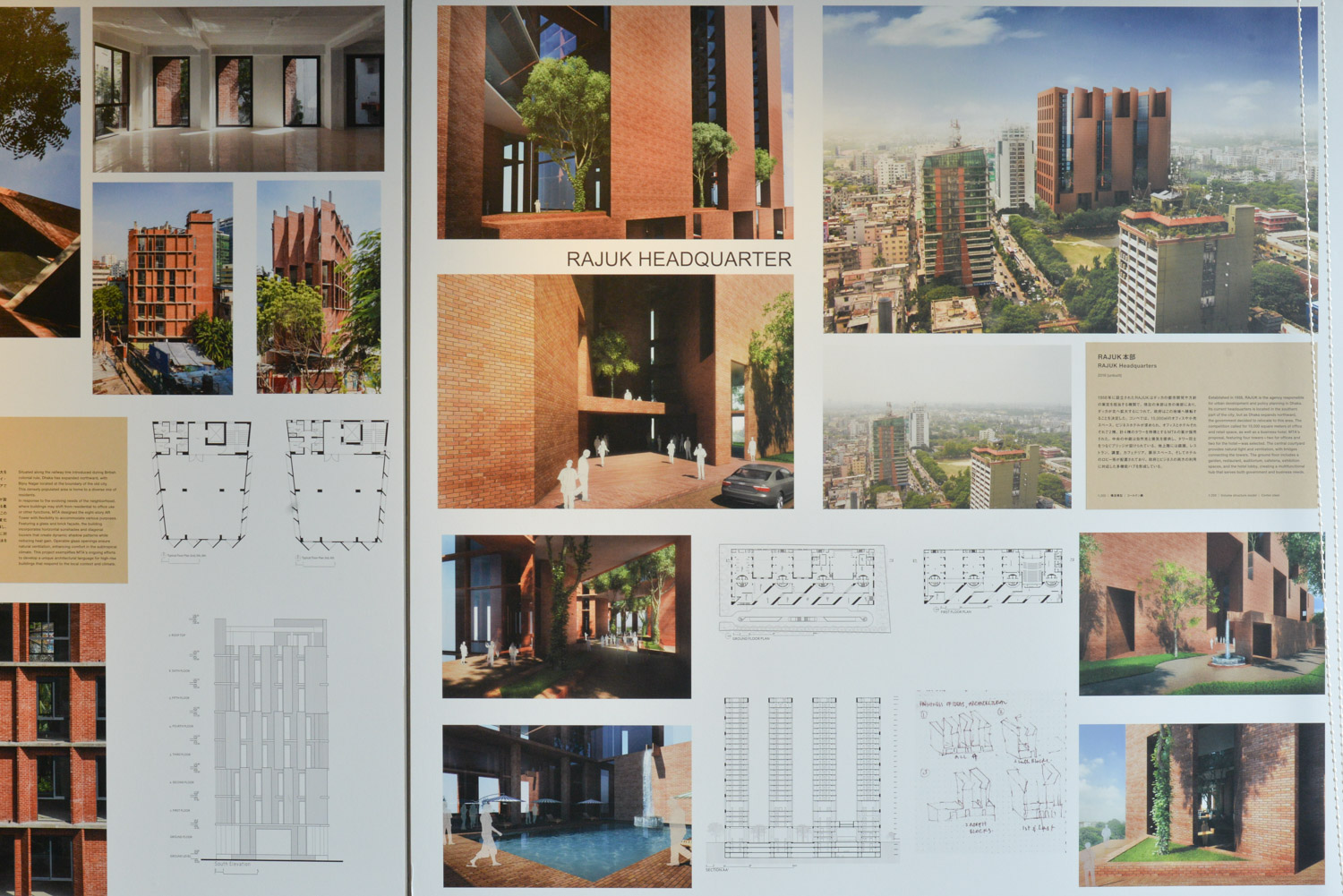

Another compelling strand of the exhibition addresses the design of vertical architecture through projects such as RAJUK Headquarters and AR Tower. When working with high-rise commercial buildings in dense urban environments, the strategy of forming thick, box-like walls to provide solar shading becomes impractical on constrained city sites. Instead, the use of vertical brise-soleil fins constructed in brick rather than concrete emerges as a locally attuned solution. This approach represents a noteworthy evolution of high-rise architecture within the context of a low-income country.

Tabassum has spoken of her material choices, noting that brick in Bangladesh is essentially fired earth. Readily available and accessible, it is inherently suited to its context and therefore a pragmatic and responsive material, much like bamboo, which is abundant and widely used across Asia. Encountering this exhibition invites a closer consideration of architectural design that earnestly addresses the realities and needs of ordinary people.

People Place Poiesis, an exhibition by Marina Tabassum Architects, is on view at TOTO GALLERY·MA from 21 November 2025 to 15 February 2026.

Photo: Nacasa & Partners

Photo: Nacasa & Partners