AN EXHIBITION FROM NAKROB MOONMANAS WHERE THE ARTIST USES COMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICS TO ANALYZE ONE OF THE LITERARY MASTERPIECES, TRIBHUMIKATA, AND CREATES A NEW STORY THAT IS FREE FROM THE ORIGINAL AUTHOR AND NARRATIVE’

TEXT: SURAWIT BOONJOO

PHOTO: PATHIPOL RATCHATAARP

(For Thai, press here)

“(…) ฝูงยมพะบาลให้เอาน้ำในอโนตัตระสระอันหอมทุกอย่าง ๒ โยชน์ก็ดีสิ่งนั้นก็ค่อยลอบถามมันว่าผิดการย์ผู้ผิดไส้ว่าชอบอย่าควรกล่าวถ้าแลเมื่อนั้นอายุเขาได้กระทำมาแต่ป่าหิมพานต์เทียรย่อมเหล็กแดงไหม้จึงจงทุกแห่งทุก (…)”

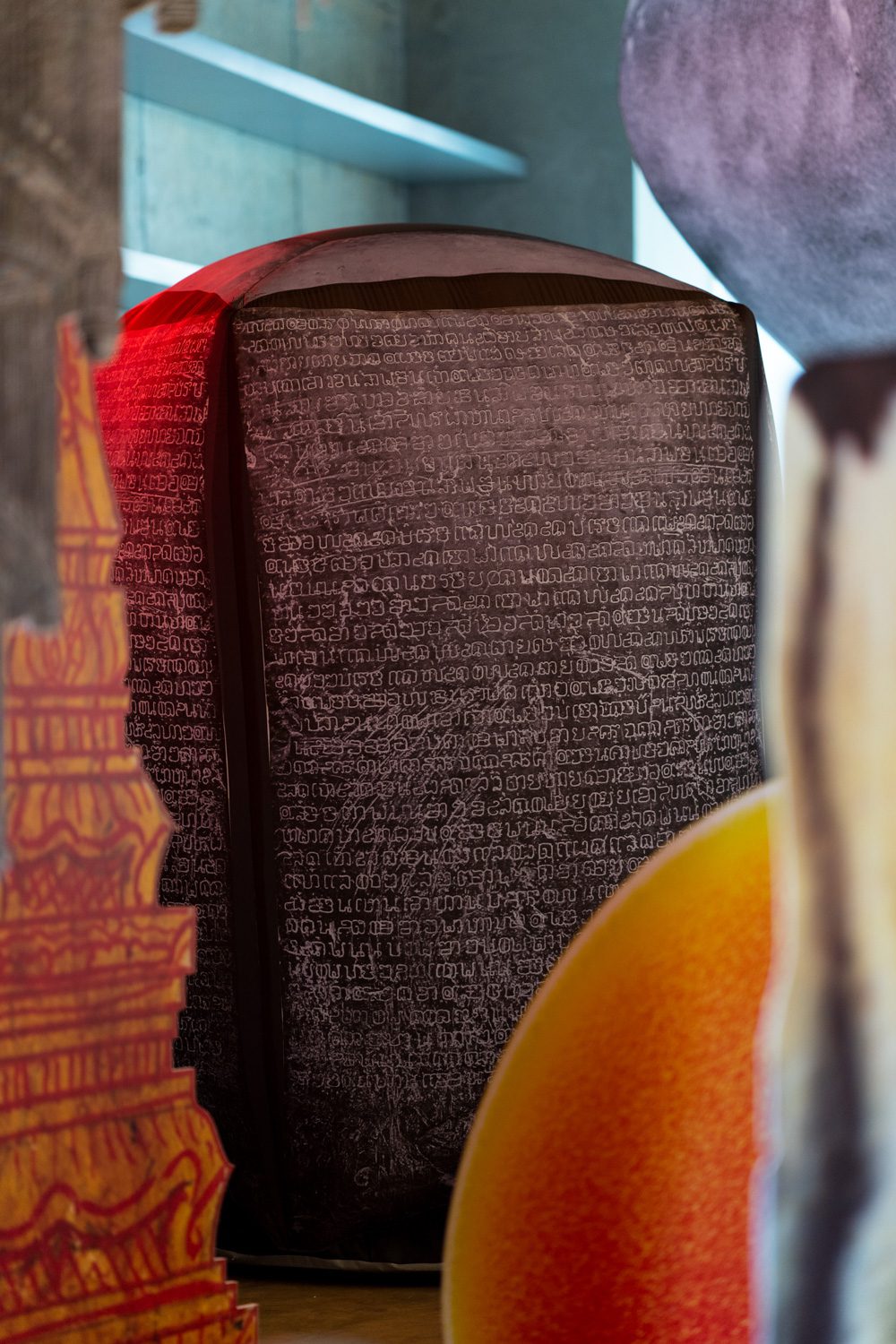

Letters are formed into words, which are then arranged in a sentence structure that appears to have no meaning. It’s part of an effort to dismantle the structure of a language by reconstructing everything using computational linguistics, with the goal of assisting in the analysis of Praya Lithai of Sukhothai’s literary masterpiece, Tribhumikata. The process results in a new literary creation that is not only an adaptation but also newly penned literature as a result of a new author’s attempt to grasp the format, structure, order of words, phrases, and sentences, as well as other aspects of the work from which it draws inspiration. This is a new literary arrangement or the latest addition to Tribhumikata, or Timirbhu, named after the title of the exhibition, Timirbhu: The New World Order, by Nakrob Moonmanas, which took place at the Jim Thompson Art Center from September 22nd to October 23rd, 2022.

The title Timirbhu is a combination and rearrangement of the original work’s name, Tri-Bhumi, and corresponds with the process of reconstructing stories to explain, narrate, and cite the new world order and cosmology in three worlds; the earth, hell, and the fall of mankind. Everything is presented as a single plane, revealing the state of chaos in the midst of the disorganized universe’s formation. The approach only selects elements of the original work to exhibit before reconfiguring and transforming the literary format into two-dimensional objects, and from two-dimensional images to installed artifacts. In some ways, it depicts the transition from ancient stories to a new tactile surface of what Dr. Chairat Pholmuk calls in his article, that is also included in the exhibition booklet as “inflatable materials filled with Kitsch artistry and blank parody.” It can be said that the original works and stories help shape and set the stage for the exhibition’s main narrative, which is told in a different interpretation to create otherness and responses while also asking questions about the details of the carefully displayed objects.

The artist disassembles and reassembles the new cosmological format using various elements of a variety of objects, such as how stars appear in the form of star-shaped objects on the floor; the ancient gods, which are symbolic forms of the sun and moon, reveal themselves in the distorted shapes created by referencing the physical characteristics of the actual sun and moon; the reversed Babel Tower; and the high and empty celestial castles erected on the long cylindrical base. The two castles pierce the open space of the library’s upper level, acting as a central pillar that pulls the cosmos together. A big pencil is also set diagonally on the floor, as are a stone inscription and an inflatable index finger, which is one of the references to René Magritte’s surrealist artwork, “La lecture défendue.” The inflated index finger emphasizes how countless stories are connected and inserted, and how everything converses and develops new meanings that travel beyond the recognized frontier. Concurrently, it represents coexistence in the form of a “multiverse,” in which multiple universes and dimensions, both similar and dissimilar, exist in parallel. The concept also applies to other exhibited items, all of which are linked at some point or through a perspective that is unique to each object’s story and existence. One can call it a different interpretation of the same story where intertextuality and the multiverse intersect in Eka-Bhumi – an extraordinarily unified world.

This literary work has a newly generated narrative, whether it is through a technological process in which a linguistic model rearranges Tribhumikata into a distinct work or how the artist produces a new story utilizing both two- and three-dimensional objects. The method intends to convey a sense of alienation and detachment from the original Tri-Bhumi. In other words, while technology is used to aid in new interpretations and stories, the artist critiques and creates a new image or impression while embellishing it with his own personal issues of interest. Both technology and the artist’s contributions raise questions and debates about the author’s role and power, which are now only left as traces symbolically represented by objects such as the pencil, stone inscription, Babel tower, typewriter, and inflated index finger (which specifically determines and dictates directions), the implication of power, as well as the original story and meanings that reference the original painting. At the same time, the criticism directed at the “author” is contradictory in terms of the function and power of the artist whose work employs the collage technique, in which images and items from various sources are combined to create a new distinct story. The method is similar to how artificial intelligence works in that it processes and generates a new language with which the story is communicated. From this point of view, one may say that both the artist’s and artificial intelligence’s creative processes highlight the back and forth questioning and answering that stems from a comparable mechanism. Apart from the citation of power and the authorship of the original work, the work creates a space for the two entities, both with the power to create, to clash and express themselves in a discernible and present manner.

A comprehensive examination and analysis of the two authors who compose the stories of the newly emerging universe takes place from the perspectives of the layered old/semi-old stories, as well as the same narrative plane where new stories are created. It extends beyond the preexisting boundary where the creator transforms letters into imagery, to a process that transcends the role of people, to the use of artificial intelligence and its digitally generated linguistic abilities, which has disrupted the role of humans as story creators. The cutting, adaption, and rearrangement underline a flight from the original narrative to otherness while retaining parts of the previous story. What one sees and reads from the exhibition is not Tribhumikata, but a ‘Eka-Bhumi (unified world)’ of chaos made up of challenges, queries, and the transition from one thing to another. This begs the question, “How far can this stage of otherness go?” Is it beyond being human or humanity itself? Or is it merely the language? That is because the new story is still told using Thai characters, combined into words, and structured into phrases and sentences based on another system and logic, the difference between which is too great for a human to comprehend.