BAUHAUS IMAGINISTA INVITES AUDIENCE TO DELVE INTO THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE LEGENDARY ART AND DESIGN SCHOOL IN CELEBRATION OF ITS 100TH ANNIVERSARY

TEXT: RAWIRUJ SURADIN

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Bauhaus is an art and design institute in Germany that has been through a number of pivotal artistic movements in the early 1920s, from the Arts and Crafts movement, Neues Bauen (new building) movement, Soviet Constructivism to the intense influences of political ideologies such as Socialism and Communism including the anti-mainstream ideology known as Spiritualism.

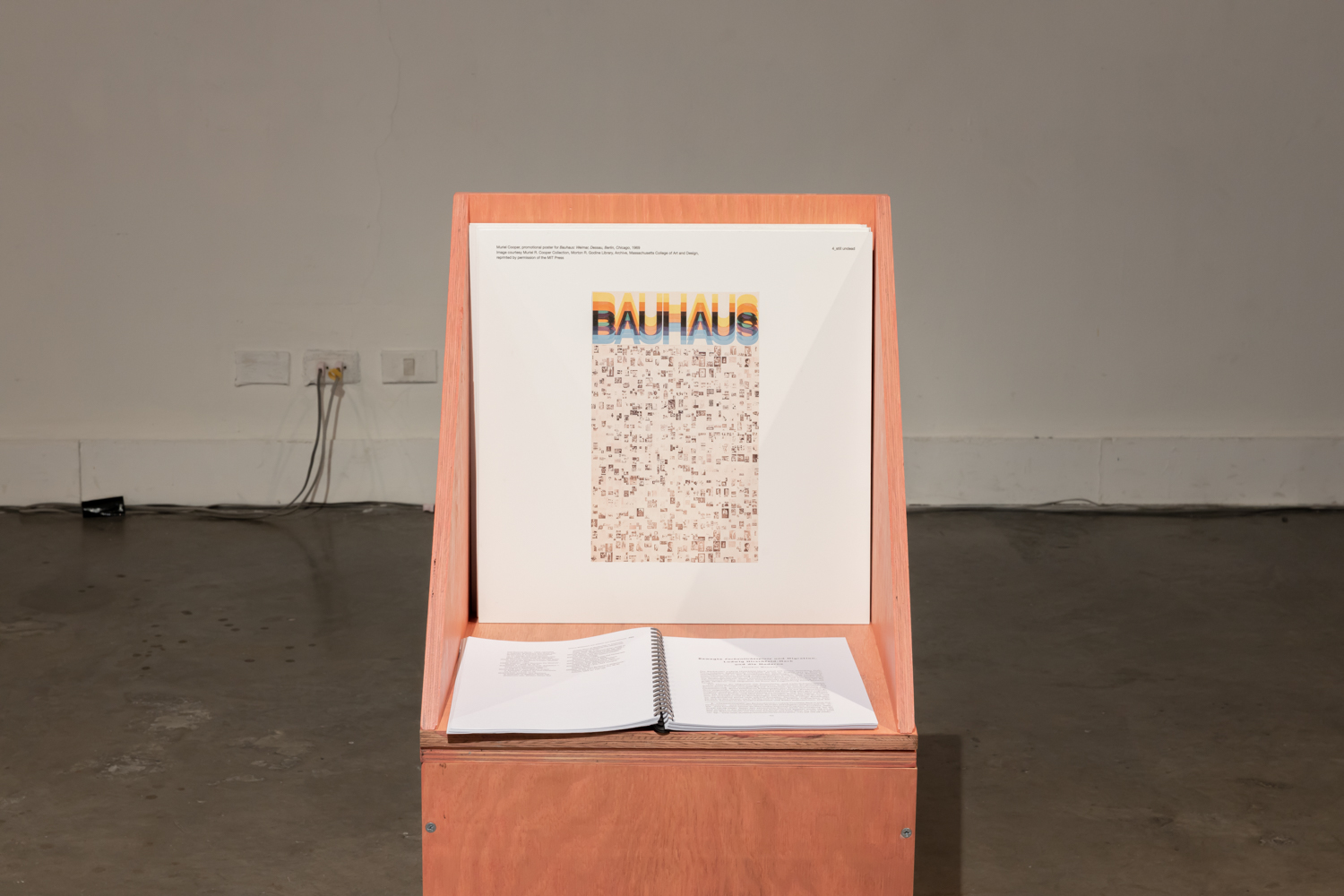

Bauhaus Imaginista is a travelling exhibition that has made its way to different cities around the world. Hosted by Goethe-Institut as a celebration of Bauhaus’ 100 Anniversary in 2019, Bangkok’s exhibition consists of 4 parts, each reconciled from 4 monumental works whose origins and existences contribute as significant parts in the history of Bauhaus.

The first part, ‘Corresponding With’, begins with the ‘Bauhaus Manifesto’ by Walter Gropius. It is the first architecture-related manifesto that expresses the basic tenets of this new school and its unique goal of bringing architects, artisans and artists together to create a new working and training community united by the primacy of architecture—“The ultimate goal of all art is the building.” The content of this particular part of the exhibition cites the relationship Bauhaus had established in its early days. After its foundation in 1919, the design institute has associated itself closely to the Modernist movement while highlighting the ideologies and practice of artisans. In addition to Bauhaus, there were other institutes that had emerged during the same time period such as Kala Bhavana, the art school of Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, India founded by Indian philosopher, Robindronath Ţhakur, in the very same year when Bauhaus was born. There was also Seikatsu Kōsei Kenkyūsho (Research Institute for Life Design) established by Renshichiro Kawakita in 1931 before it later changed its name to Shinkenchiku Kōgei Gakuin (School of New Architecture and Design). The relationship between these institutes is told through a number of works created by both students and teachers, as well as the now rare teaching documents that were being used at the schools.

‘Learning From’, the second part of the exhibition, is reconciled from the work titled Teppich (Carpet) by Paul Klee in 1927. It revolves around the study and application of cultural objects and thinking outside of mainstream Modernism, particularly from the sources outside of the western world (but they are still included local European traditions and norms), all the way to the works by marginalized artists and children. The interest is specifically focused on the pre-Modern objects that are still widely popular even after Bauhaus was forced to close down in 1933. Bauhaus’ interest and questioning in the definitions of high and low art also spawned several other conversations concerning the binary opposition of the West and non-West, the notion of us/otherness, which were all relatable to the questions about the borrowing and exchanges of culture during the Colonial Era in Europe, North America and South America.

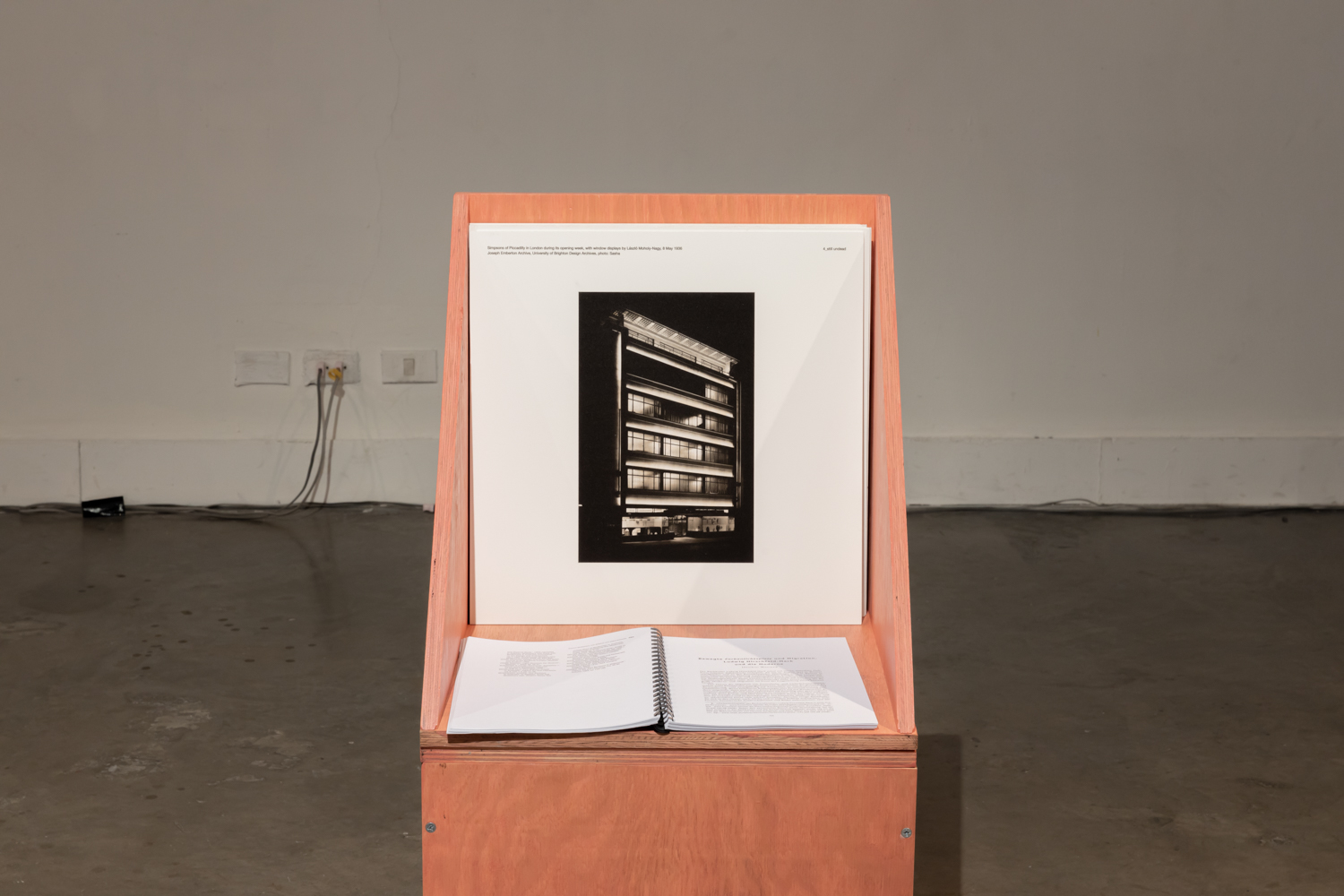

Marcel Breuer’s collage ein bauhaus-film. fünf jahre lang (a bauhaus film. five years long) is the starting point of ‘Moving Away’, the third part of the exhibition. Breuer’s film roll presents the development of the design of a chair, from a handcrafted object to the factory-made prototype. The relocation of Bauhaus before its eventual closure in 1933 after the rise of the Nazi party caused Bauhaus’ teachers and students to flee from Germany, followed by the dispersion of the Bauhaus personnel in different areas of the world. Such incidents can be associated with the changes in the design-related dialogues in the early 20s, which also bore certain connections with the areas’ social and geographical conditions as witnessed in case studies in the Soviet Union, India, China, Taiwan, North Korea and Nigeria.

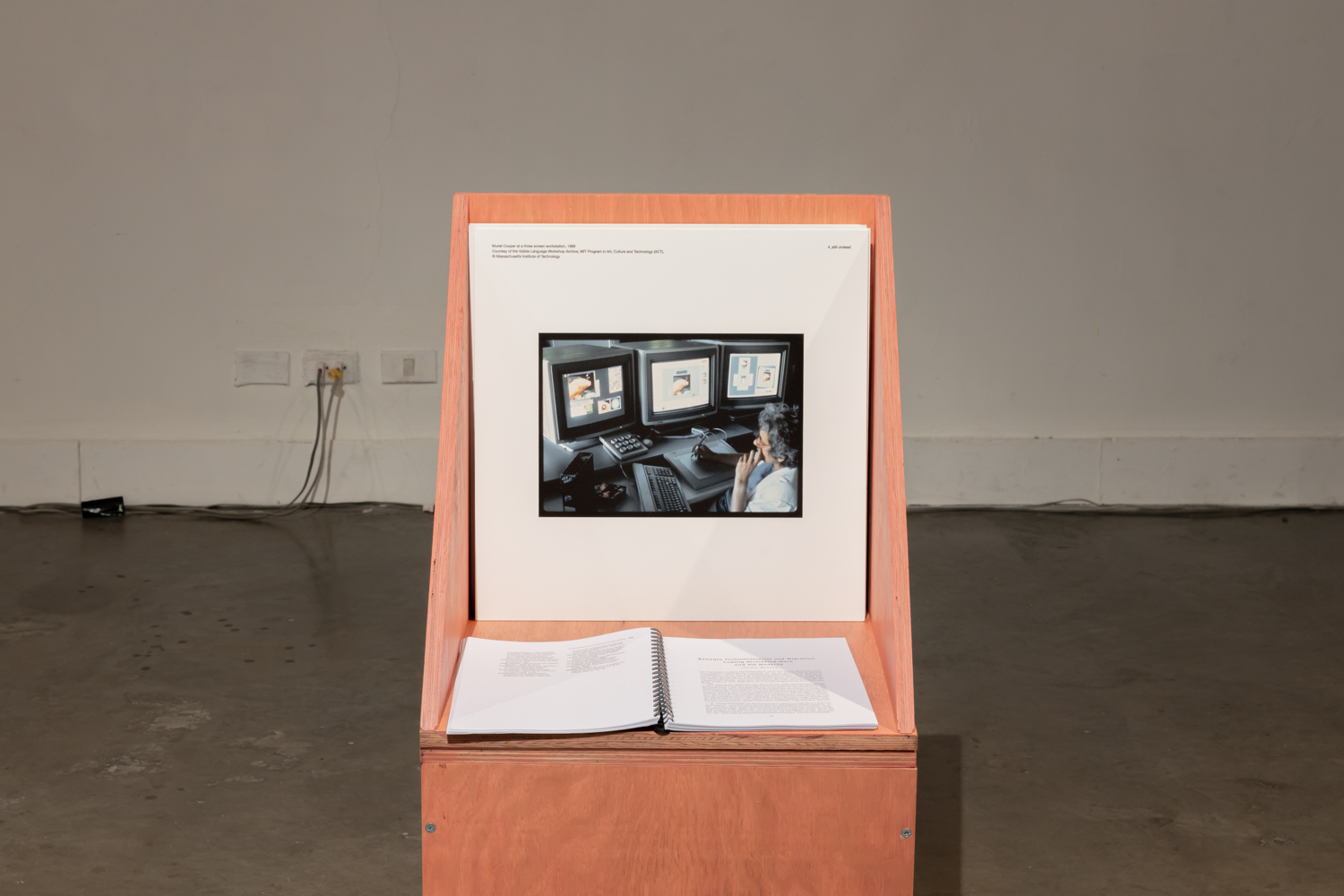

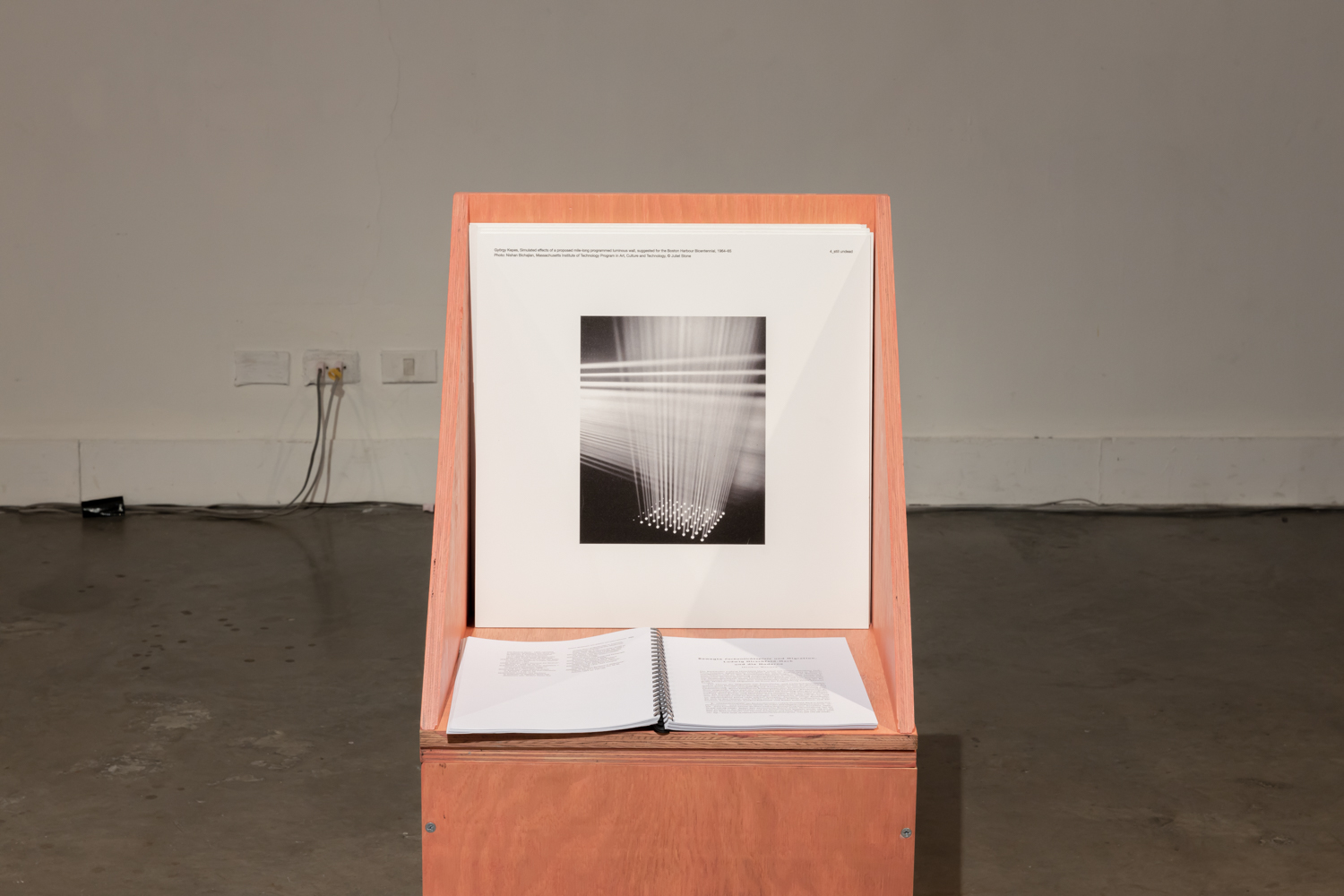

‘Still Undead’, the last part of the exhibition, has Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (Reflective colored light plays, 1922) by Kurt Schwerdtfeger as its genesis. Schwerdtfeger’s work, which was once exhibited in Wassily Kadinsky’s apartment space, is considered to be a significant milestone that eventually leads up to the birth of an artistic medium later known as Expanded Cinema (from the book with the same name by art theorist Gene Youngblood). The movements through the lights and shadows of abstract forms and sounds in this work marked the beginning that was later ensued by experiments on lights, sounds and new technologies in art schools and universities today; be there the New Bauhaus in Chicago, or the Centre for Advanced Visual Studies (CVAS) and the Media Lab of MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

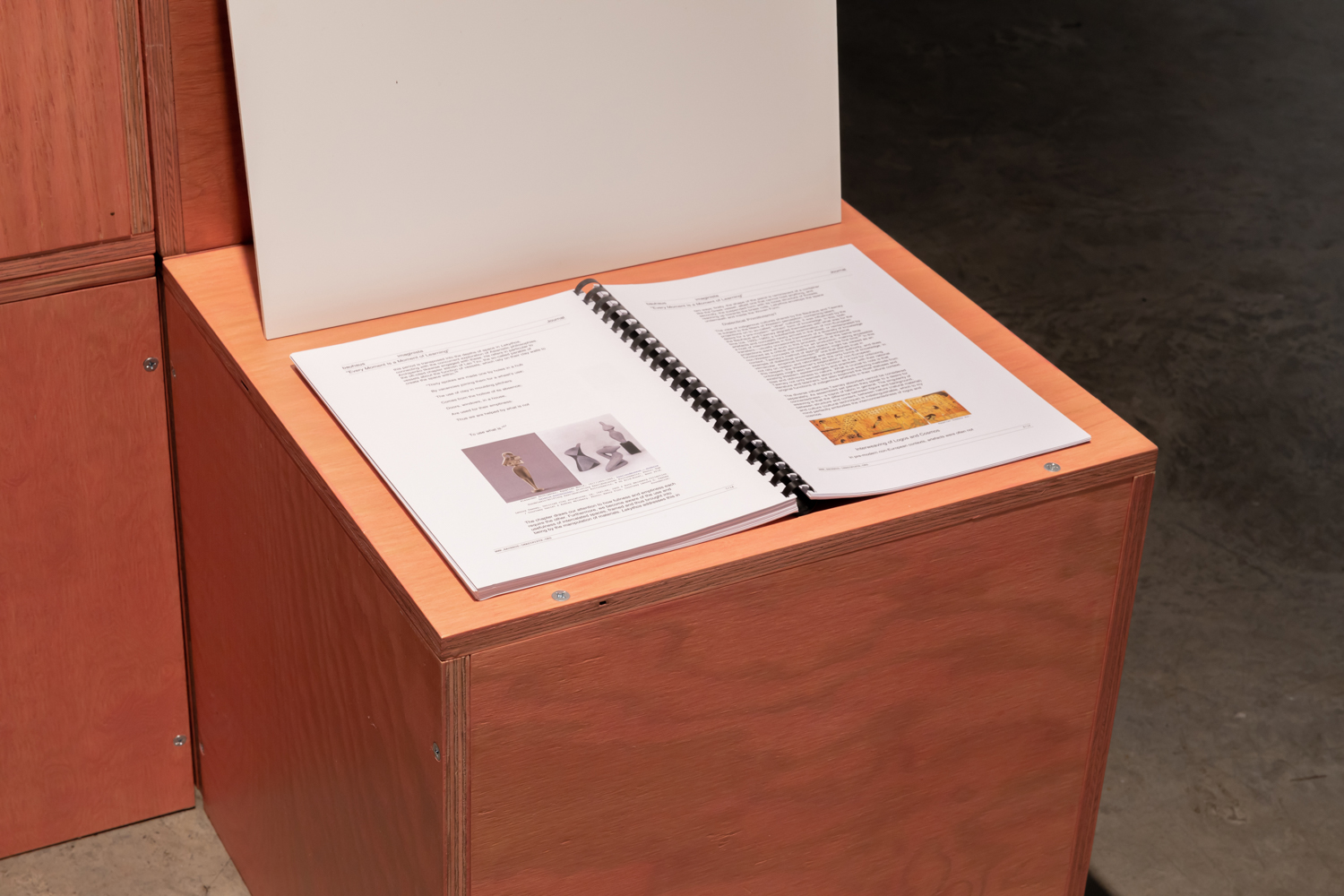

The exhibition in Bangkok takes place on the fourth floor of Bangkok Art and Culture Center. Several wooden boxes are made of a bunched of square wooden panels dyed in light red for the sculpture titled ‘Bauhaus Jukebox’ by Swiss artist, Luca Frei. The boxes are scattered in different parts of the exhibition, serving as shelves where documents and pamphlets with information about the four parts of the exhibition are placed. Also provided is a printing station where information from online archives can be printed, and a VR tool that allows viewers to experience and interact with the Bauhaus atmosphere in the form of virtual reality. While hard copy documents are only a fraction of the entire database, which brings together a vast collection of articles, academic works, researches, documents, interview transcriptions, photographs, etc. from the past, the results generated from this exhibition can also be accessed via Bauhaus Imaginista’s online database (bauhaus-imaginista.org).

What’s special about Bauhaus Imaginista and the nature of it being a traveling exhibition that allows for it to move around from one city to another, is the fact that it can depict the relationship between the Bauhaus philosophy and the space it visits. From a school to a monumental movement, Bauhaus has evolved, connected and influenced an endless number of people from architects, artists, academics, and students. Bauhaus Imaginista has shown us once and for all the impacts the ideology of this highly influential art and design institute has on its own surrounding context, from social sciences, anthropology, politics, etc. and vice versa where the changes of these factors has shaped and shifted Bauhaus into what it was then and what it is now.