‘FOUR PLAYS,’ PUBLISHED IN ART4D #114 BACK IN 2005, WHEN TADAO ANDO HAS RECENTLY COMPLETED A NEW CHICHU ART MUSEUM ON THE REMOTE NAOSHIMA ISLAND. WRITTEN BY CHAIYOSH ISAVORAPANT WHO PAYS A VISIT

TEXT: CHAIYOSH ISAVORAPANT

PHOTO: MITSUO MATSUOKA

(For Thai, press here)

“What is art?” the question has motivated many in the art world to seek answers throughout the entire 20th century, and now into the 21st. This question has itself required clarification by means of other questions, from “How does art represent the age?” or “How does it reflect the society or the economy of its time?” to “Is art the creation of the artist, or does it depend on the primary discourse going on in his/her environment?” Other questions of a similar nature might include, “Can art be copied?”, the highly challenging “Does art have any real content, or is it all form?”‘, and, ultimately, “What relation does art have to the individual in terms of what one learns or how one lives?”

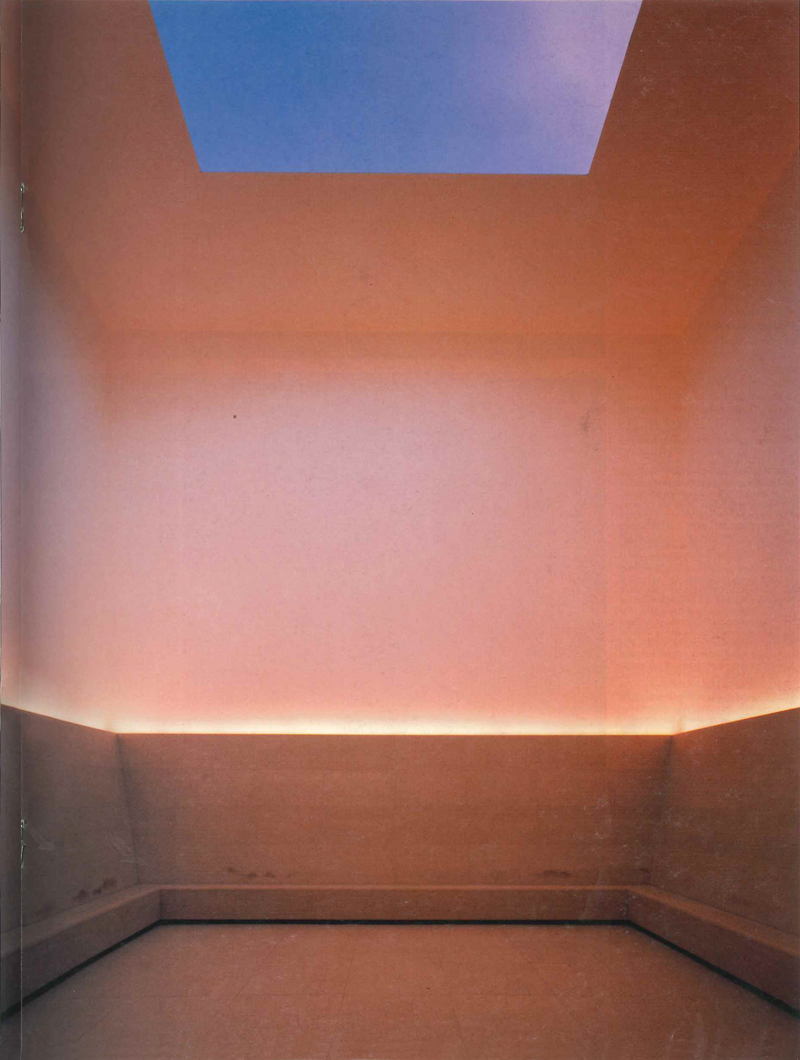

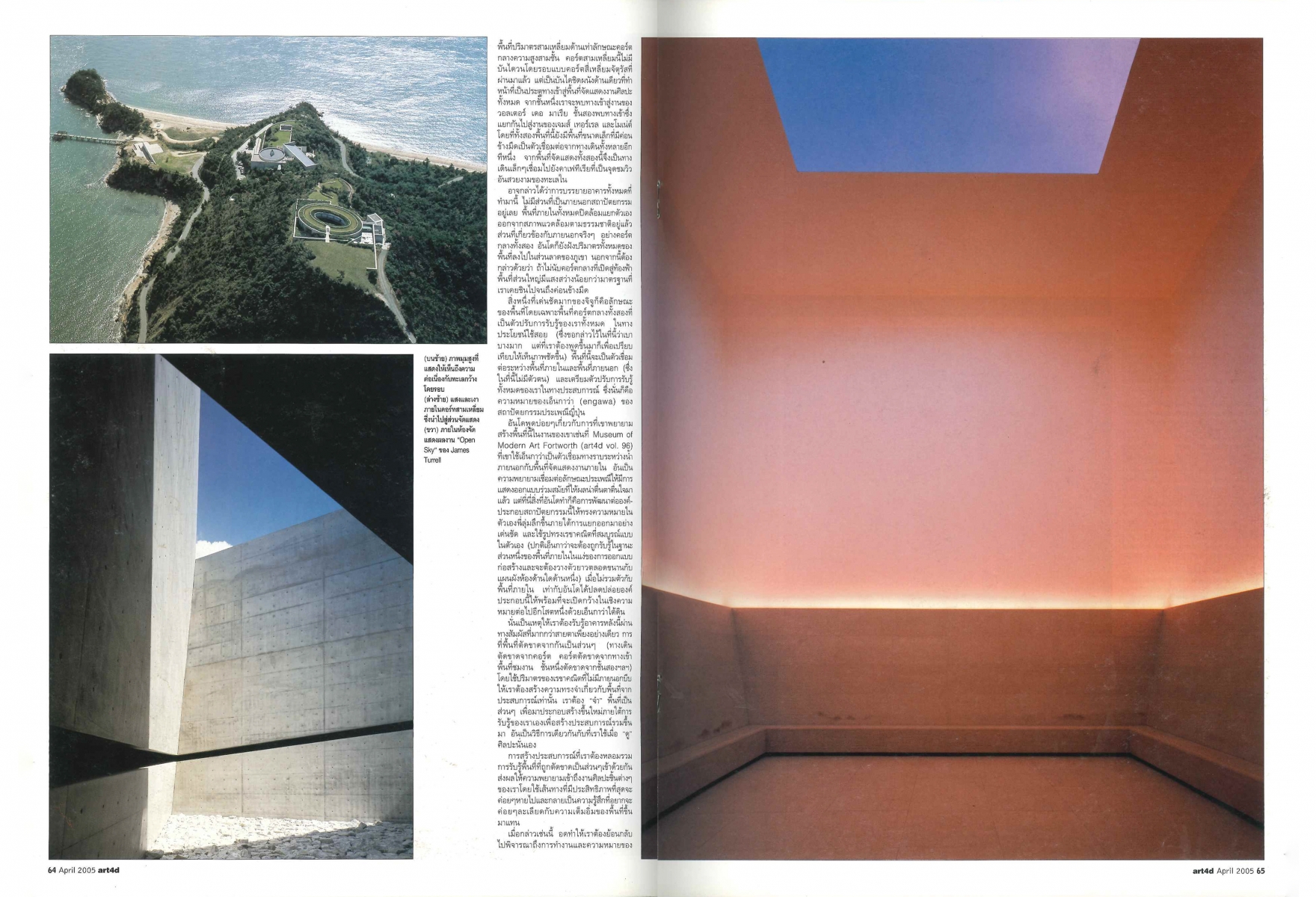

These questions are of direct relevance to the design of museums, where art is on display. As a designer of many museums, Tadao Ando has provided one particular answer at the Chichu Museum on the island of Naoshima, far from Japan’s main cities. But before we consider its architecture, we must look at its art. At Chichu, only three artists are on display. There are five pieces by Monet, namely the “Water Lily” collection, the installations-cum-sculpture of American artist Walter de Maria, and the experiments in light made by James Turrell. Chichu Art Museum is clearly an unconventional venue for art. Monet represents the ‘classic’ side, while the two other artists are modern, living innovators Turrell’s work, in particular, is more like a performance than simply ‘still’ art.

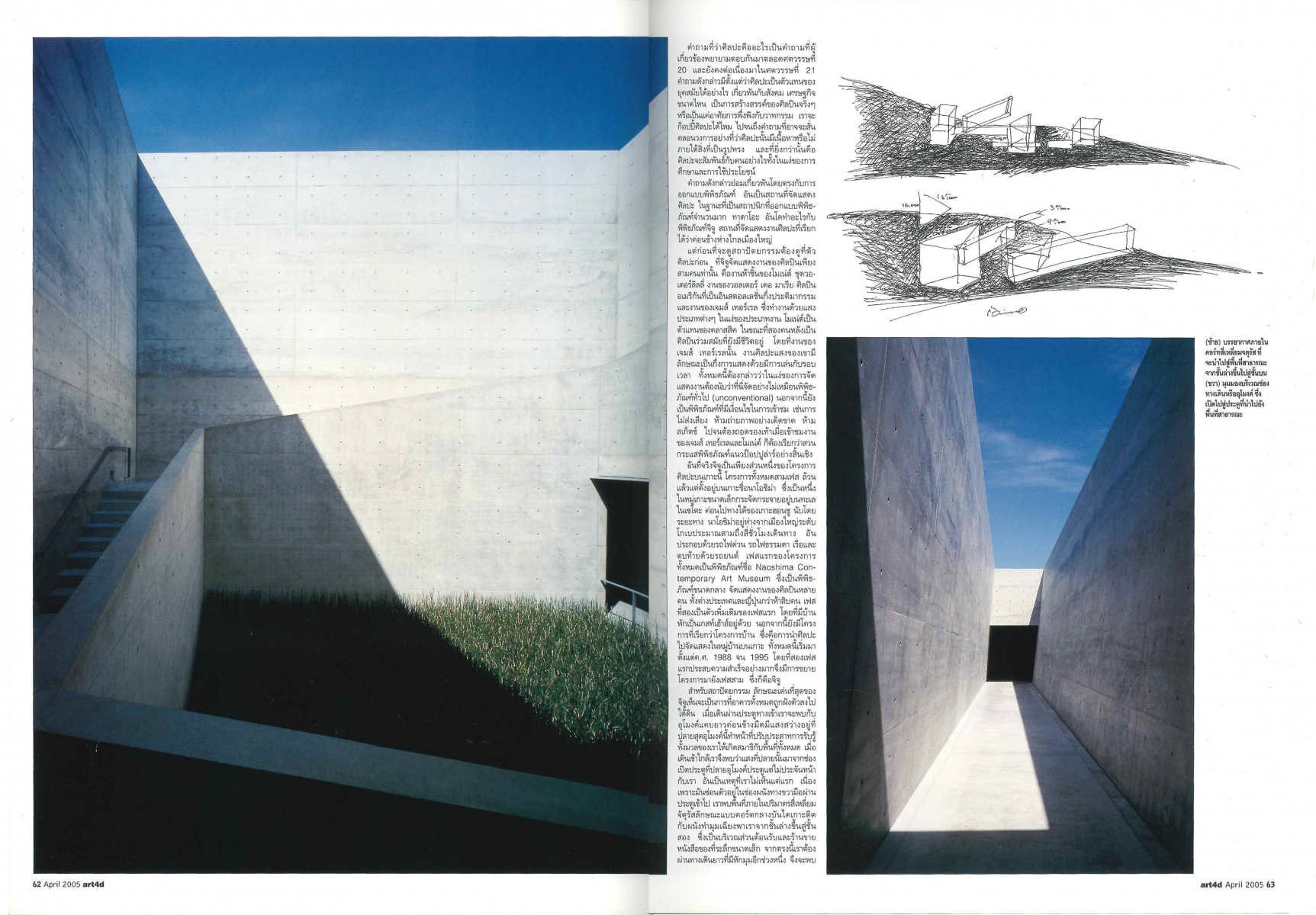

Actually, Chichu Art Museum is but one part of a three-phase art program being implemented on this island. The first phase is the Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum, a mid-sized museum featuring the work of more than fifty international and local artists. The second phase is an extension of the first, with guest houses included. The third phase involves the display of artworks in villages all over the island. Running from 1988 to 1995, the first two phases have achieved great success, thus spawning the third phase that comprises Chichu Art Museum.

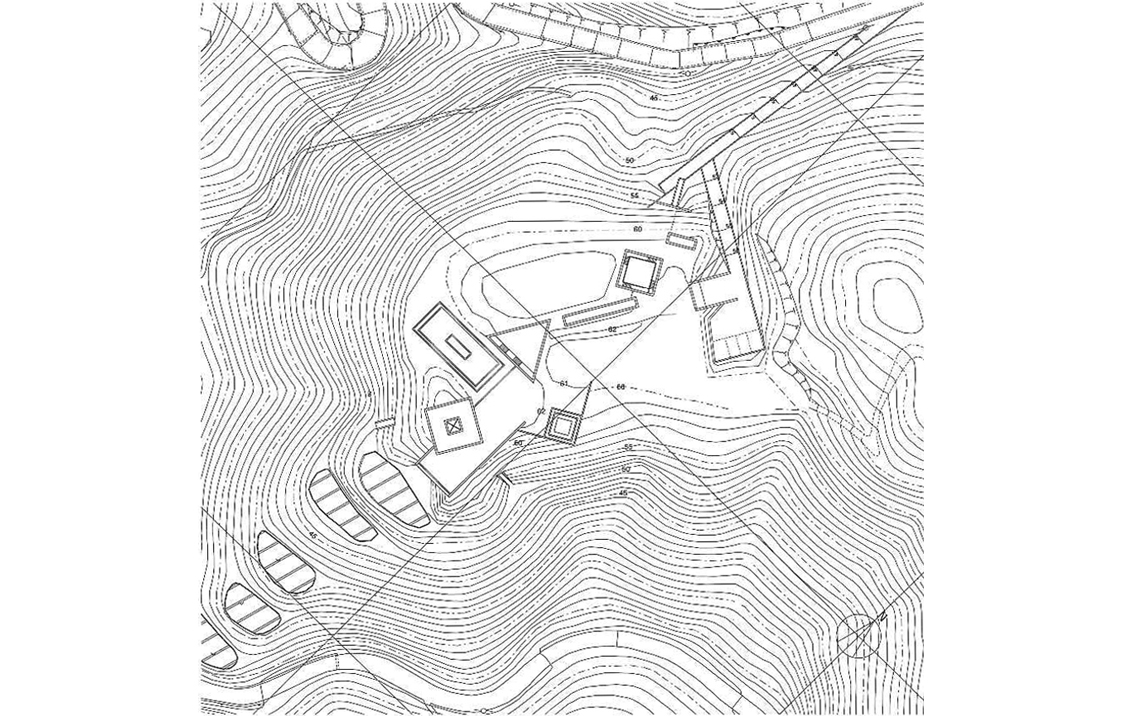

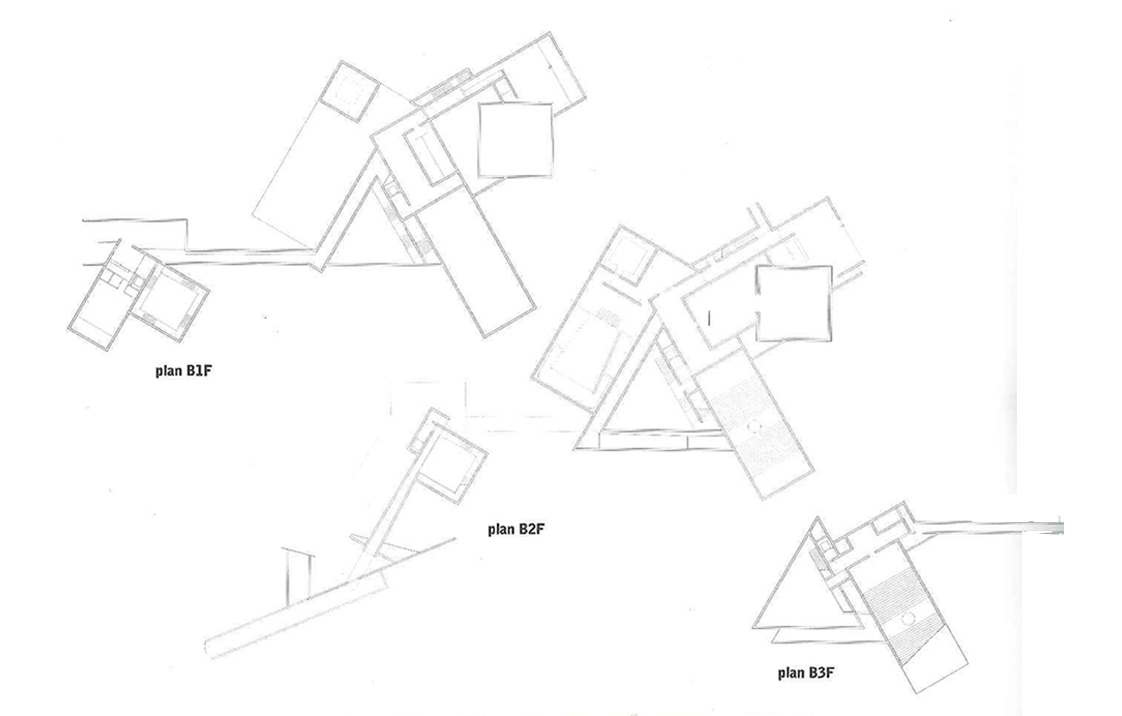

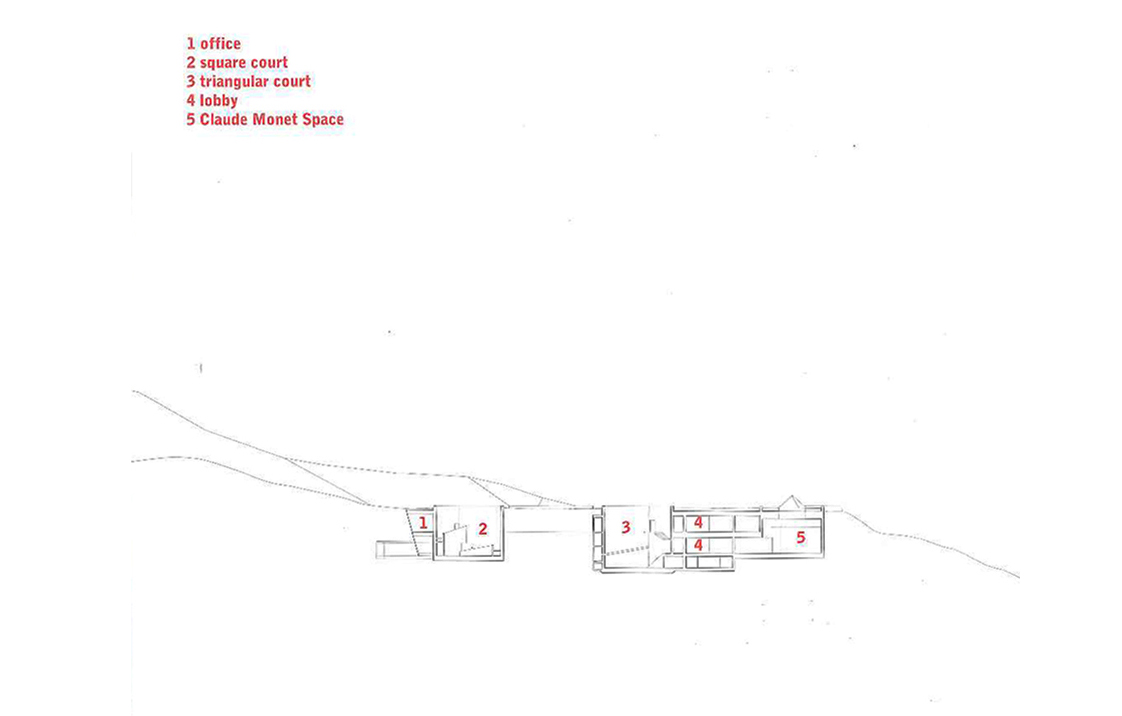

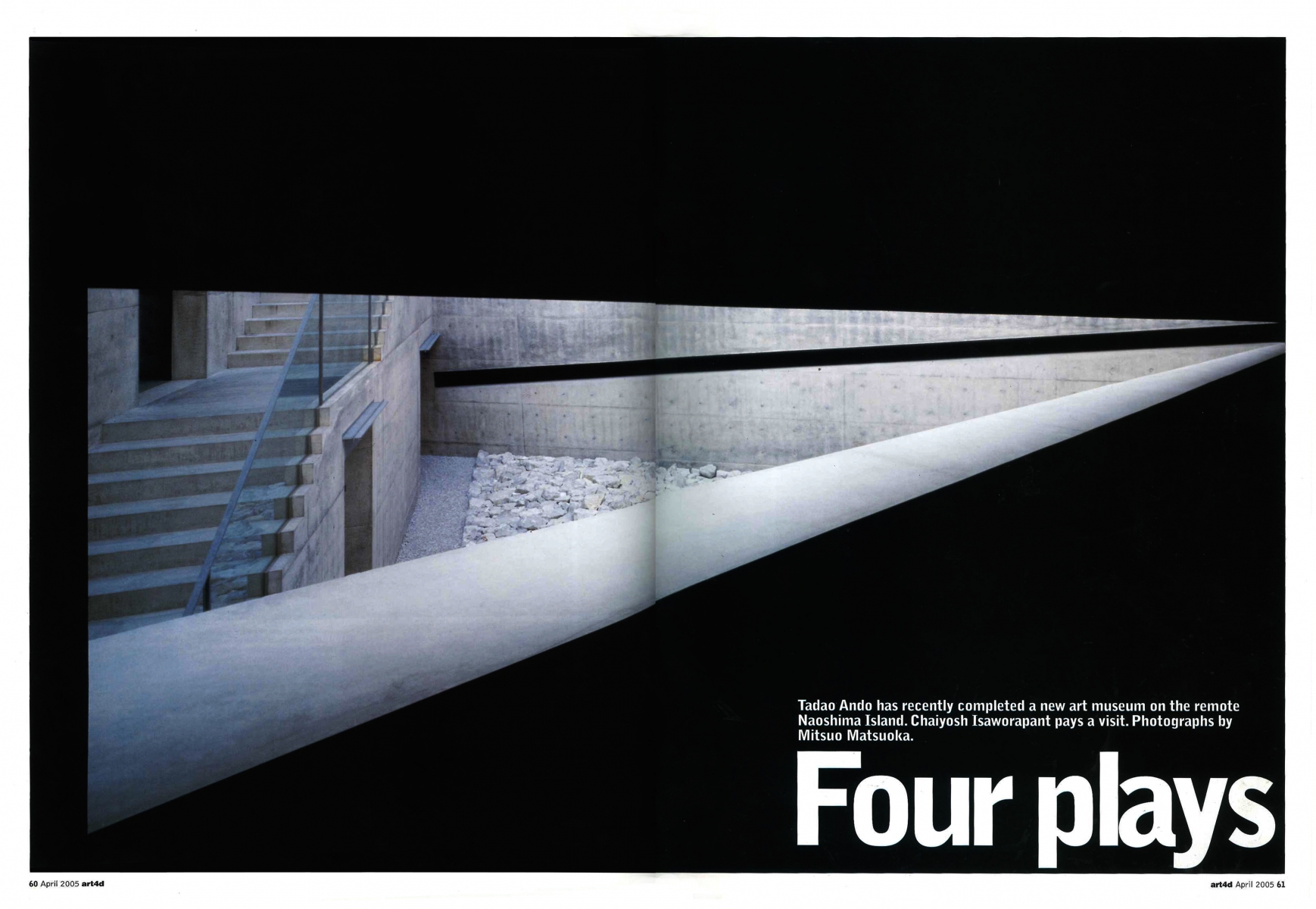

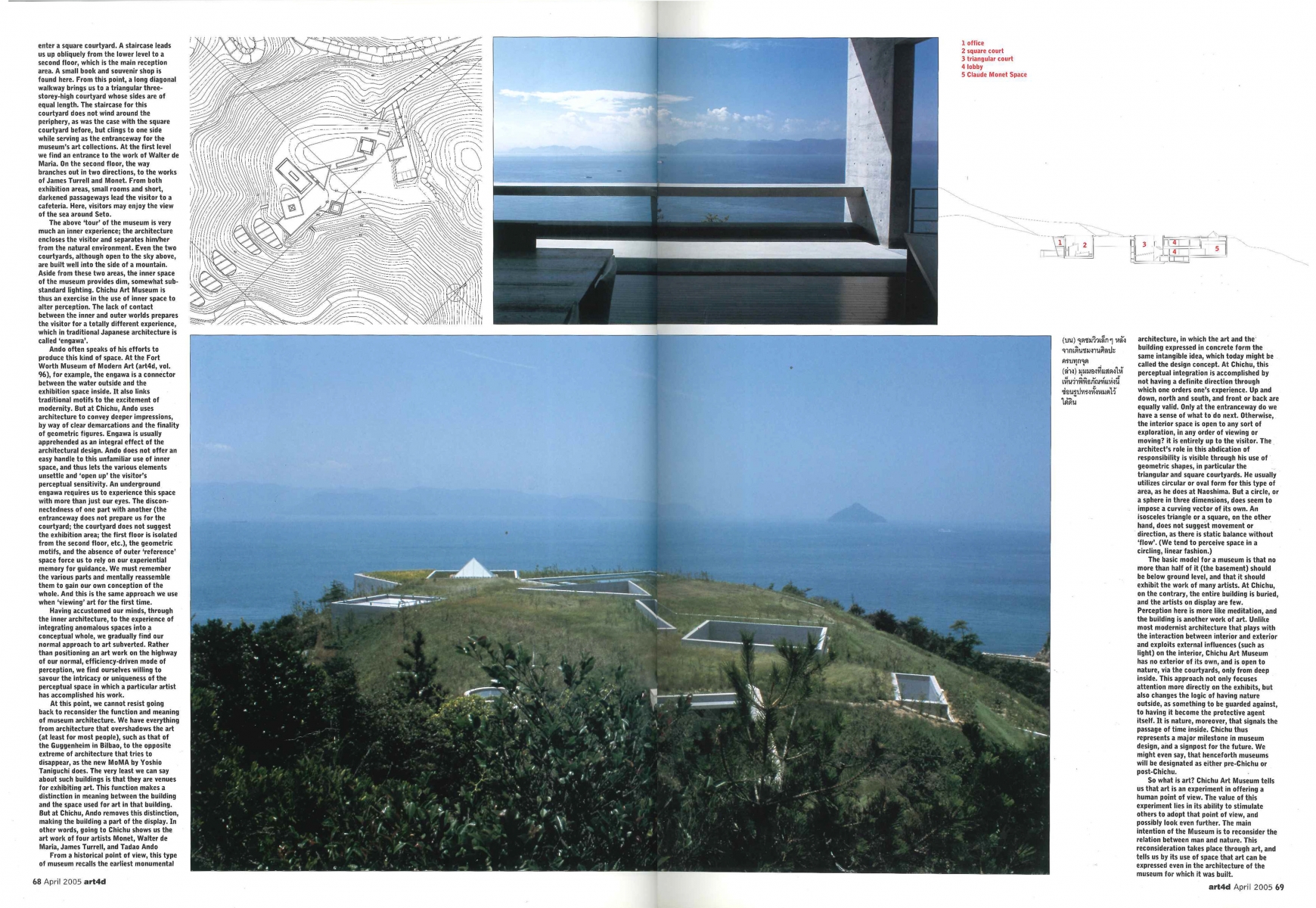

The most notable feature of the architecture at Chichu is that all the buildings are built deep into the ground. After entering by the main entrance, we come to a long, narrow, rather dark tunnel, at the end of which bright light is visible. The effect of this entrance is to calm our senses and adjust them to the site. As we approach the end of the tunnel, we see that the light is coming from a doorway. The door, however, is not facing us, which is why we did not see it at first, but is enclosed by the wall to the right.

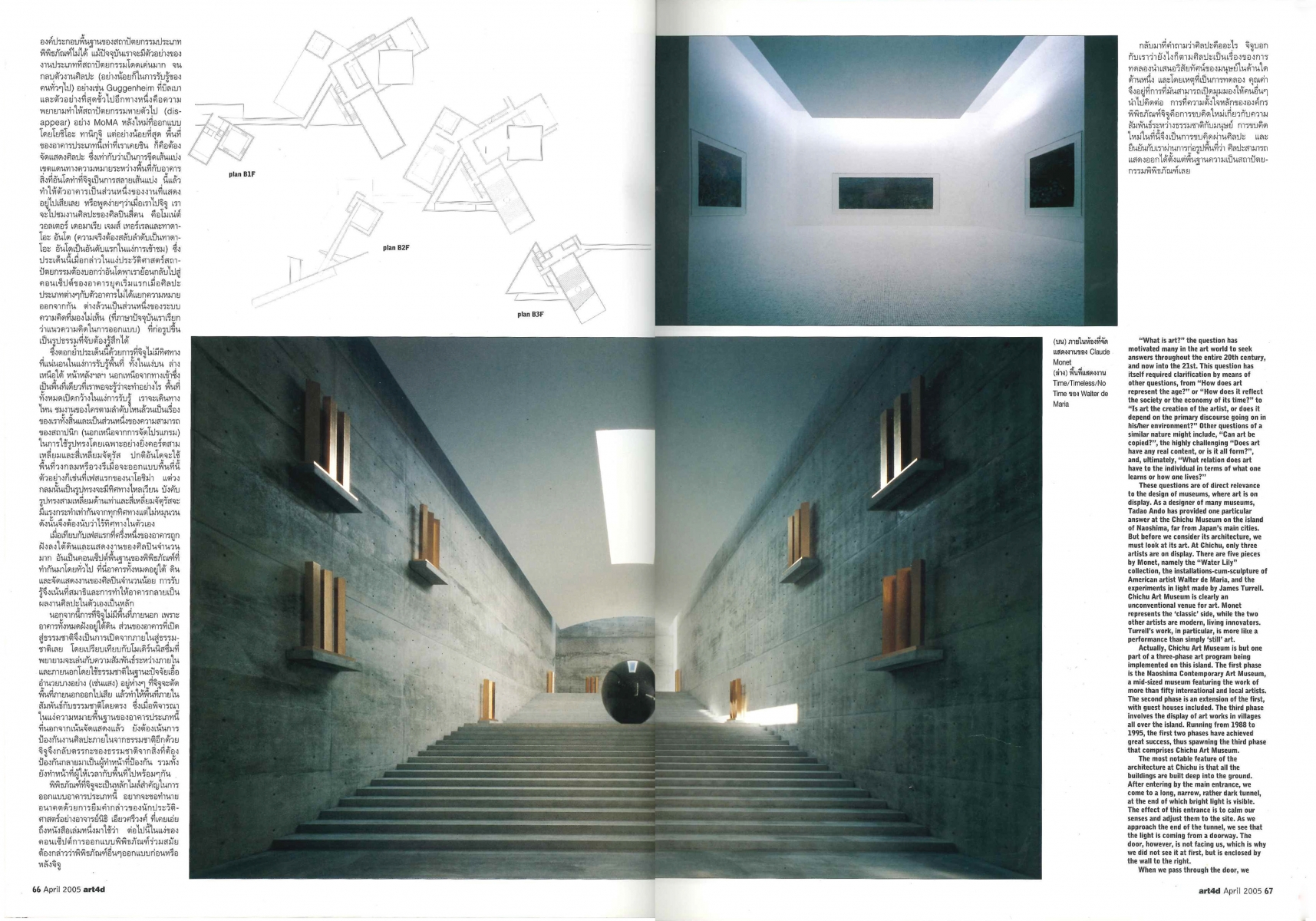

When we pass through the door, we enter a square courtyard. A staircase leads us up obliquely from the lower level to a second floor, which is the main reception area. A small book and souvenir shop is found here. From this point, a long diagonal walkway brings us to a triangular three-storey-high courtyard whose sides are of equal length. The staircase for this courtyard does not wind around the periphery, as was the case with the square courtyard before, but clings to one side while serving as the entranceway for the museum’s art collections. At the first level we find an entrance to the work of Walter de Maria. On the second floor, the way branches out in two directions, to the works of James Turrell and Monet. From both exhibition areas, small rooms and short, darkened passageways lead the visitor to a cafeteria. Here, visitors may enjoy the view of the sea around Seto.

The above ‘tour’ of the museum is very much an inner experience; the architecture encloses the visitor and separates him/her from the natural environment. Even the two courtyards, although open to the sky above, are built well into the side of a mountain. Aside from these two areas, the inner space of the museum provides dim, somewhat substandard lighting. Chichu Art Museum is thus an exercise in the use of inner space to alter perception. The lack of contact between the inner and outer worlds prepares the visitor fora totally different experience, which in traditional Japanese architecture is called ‘engawa’.

Ando often speaks of his efforts to produce this kind of space. At the Fort Worth Museum of Modern Art (art4d, vol. 96), for example, the engawa is a connector between the water outside and the exhibition space inside. It also links traditional motifs to the excitement of modernity.But at Chichu, Ando uses architecture to convey deeper impressions, by way of clear demarcations and the finality of geometric figures. Engawa is usually apprehended as an integral effect of the architectural design. Ando does not offer an easy handle to this unfamiliar use of inner space, and thus lets the various elements unsettle and ‘open up’ the visitor’s perceptual sensitivity. An underground engawa requires usto experience this space with more than just our eyes. The disconnectedness of one part with another (the entranceway does not prepare us for the courtyard; the courtyard does not suggest the exhibition area; the first floor is isolated from the second floor, etc.), the geometric motifs, and the absence of outer ‘reference’ space force us to rely on our experiential memory for guidance. We must remember the various parts and mentally reassemble them to gain our own conception of the whole. And this is the same approach we use when ‘viewing’ art for the first time.

Having accustomed our minds, through the inner architecture, to the experience of integrating anomalous spaces into a conceptual whole, we gradually find our normal approach to art subverted. Rather than positioning an art work on the highway of our normal, efficiency-driven mode of perception, we find ourselves willing to savour the intricacy or uniqueness of the perceptual space in which a particular artist has accomplished his work.

At this point, we cannot resist going back to reconsider the function and meaning of museum architecture. We have everything from architecture that overshadows the art (at least for most people), such as that of the Guggenheim in Bilbao, to the opposite extreme of architecture that tries to disappear, as the new MOMA by Yoshio Taniguchi does. The very least we can say about such buildings is that they are venues for exhibiting art. This function makes a distinction in meaning between the building and the space used for art in that building. But at Chichu, Ando removes this distinction, making the building a part of the display. In other words, going to Chichu shows us the art work of four artists Monet, Walter de Maria, James Turrell, and Tadao Ando.

From a historical point of view, this type of museum recalls the earliest monumental architecture, in which the art and the building expressed in concrete form the same intangible idea, which today might be called the design concept. At Chichu, this perceptual integration is accomplished by not having a definite direction through which one orders one’s experience. Up and down, north and south, and front or back are equally valid. Only at the entranceway do we have a sense of what to do next. Otherwise, the interior space is open to any sort of exploration, in any order of viewing or moving? it is entirely up to the visitor. The architect’s role in this abdication of responsibility is visible through his use of geometric shapes, in particular, the triangular and square courtyards. He usually utilizes circular or oval form for this type of area, as he does at Naoshima. But a circle, or a sphere in three dimensions, does seem to impose a curving vector of its own. An isosceles triangle or a square, on the other hand, does not suggest movement or direction, as there is static balance without ‘flow’. (We tend to perceive space in a circling, linear fashion.)

The basic model for a museum is that no more than half of it (the basement) should be below ground level, and that it should exhibit the work of many artists. At Chichu, on the contrary, the entire building is buried and the artists on display are few.

Perception here is more like meditation, and the building is another work of art. Unlike most modernist architecture that plays with the interaction between interior and exterior and exploits external influences (such as light) on the interior, Chichu Art Museum has no exterior of its own, and is open to nature, via the courtyards, only from deep inside. This approach not only focuses attention more directly on the exhibits, but also changes the logic of having nature outside, as something to be guarded against, to having it become the protective agent itself. It is nature, moreover, that signals the passage of time inside. Chichu thus represents a major milestone in museum design, and a signpost for the future. We might even say, that henceforth museums will be designated as either pre-Chichu or post-Chichu.

So what is art? Chichu Art Museum tells us that art is an experiment in offering a human point of view. The value of this experiment lies in its ability to stimulate others to adopt that point of view, and possibly look even further. The main intention of the Museum is to reconsider the relation between man and nature. This reconsideration takes place through art, and tells us by its use of space that art can be expressed even in the architecture of the museum for which it was built.

Originally published in art4d #114, April 2005