IN 2013, CHAVALIT SOEMPRUNGSUK RETURNS TO BANGKOK TO SHARE NOT ONLY HIS WORKS BUT ALSO THE STUDIO THAT NURTURED THEM. THE EXHIBITION AT THE RATCHADAMNOEN CONTEMPORARY ART CENTER PROVIDES A BEHIND THE SCENES LOOK AT BOTH ARTIST AND WORKS

TEXT: REBECCA VICKERS

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

There are reasons to pursue artistic practice beyond recognition, approval or praise. There is the pleasure of the work in itself, a curiosity for the material, the sense of fulfillment that can only be obtained through harnessing expression into form by the act of one’s own hand, and, perhaps the most uncompromising reason of any, a tireless desire to explore through the act of creation and a respect for the practice, as practice. But can these reasons function as motivations that could last past a fleeting interest or culminate into something larger than, even a long-term, hobby? Could they, define one’s direction – for life?

For Chavalit Soemprungsuk, deference for the practice of art, as practice, has, for as long as he can remember, defined the only path worth pursuing, the only path possible. “I was born as an artist, nothing else. I cannot live without art. I knew when I was very young, that it was the only thing I could do. There are some people who can do many things, they are clever. But I am not clever, I have a bad memory, I am very bad with language, I am very bad with mathematics, I don’t remember things, but the only thing that I know is that I want to create art, that is my life, the whole life. I was born an artist; I will die an artist, it’s simple.”

Soemprungsuk graduated from the Faculty of Painting, Sculpture and Graphic Arts, Silpakorn University in 1962 where he studied with the late Ajarn Silpa Bhirasri prior to moving to the Netherlands to continue his studies at Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Royal Academy of Visual Arts), Amsterdam in 1963. Soemprungsuk described that he “wanted to stay in Europe because I didn’t see a real future for artists in Thailand at that time, Thailand wasn’t a really good place for artists to live – as an artist.” His time at the academy in Amsterdam was, however, short lived, as a disagreement with a professor resulted in the young, and determined in more ways that one, artist getting kicked out of the academy altogether. “The professor sent me to draw a cow in a field, and capture every single hair on the cow. I didn’t want to do that. At that time, Dutch professors were very conservative and he didn’t accept my work if I drew only a few lines. There was no point in arguing with him. After that, I found a job, I did this, I did that. At the same time, I had to also find time to work – for art, my time was split half, half. After four years I presented my work to the government and applied to be accepted into the system of government-sponsored artists. This system began after World War II when the government realized that they had let some artists, like Van Gogh, die, for nothing, hungry and so on. They learned their lesson and after the war they built up a kind of institution to support artists and let them live normally without having to worry about money. They offered the artists a salary every month for the whole year allowing them to work only for art.” In 1970, Soemprungsuk became the first, and only, Thai artist to be named a government-sponsored artist of the Netherlands. “This gave me enough time to continue working freely. That is the luck I had.”

Somprungsuk fulfilled the role of a government-sponsored artist for nearly the next twenty years, living, working and focusing all of his attention on his art practice in a modest studio in Amsterdam Oost, a borough of Amsterdam comprised of the Zeeburg and neighboring districts where he has continued living and working for the past 50 years. While the undeniably impressive body of work the artist created during this time, some 2,000 plus expressions and explorations into a diverse range of media and techniques including painting, printmaking, mixed media, installation and sculptural works, are without doubt objects of great value on their own, the artist’s unfaltering commitment to the practice is equally commendable. His work developed in tandem with his life, as his life was his work. “Art cannot be compromised, and to whom is it to be compromised to? You cannot do it half way through. You need to stretch to the edge. You have to devote one hundred percent; one thousand percent.”

It is this, Soemprungsuk’s persistent and unfaltering respect for the practice, that one finds, today, housed within the walls of the new Ratchadamnoen Contemporary Art Center in Bangkok, Thailand. The exhibition, ‘In Amsterdam, with Chavalit Soemprungsuk,’ was initiated by a proposal from the artist to the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture, Ministry of Culture, Thailand. Soemprungsuk approached the OCAC and offered to donate not only his life’s work, but also his entire studio, collection of over 1,000 books, personal belongings, and mementos of his lifelong journey living and working as an artist, to the Thai people. “I want to let the Thai public see how I lived in Amsterdam and how I spent my life working for the past 50 years. You get the smell, the atmosphere, the feeling, everything – how I lived. I hope to give a kind of inspiration to the young artist, to the Thai people, to see what it is like to live with art.”

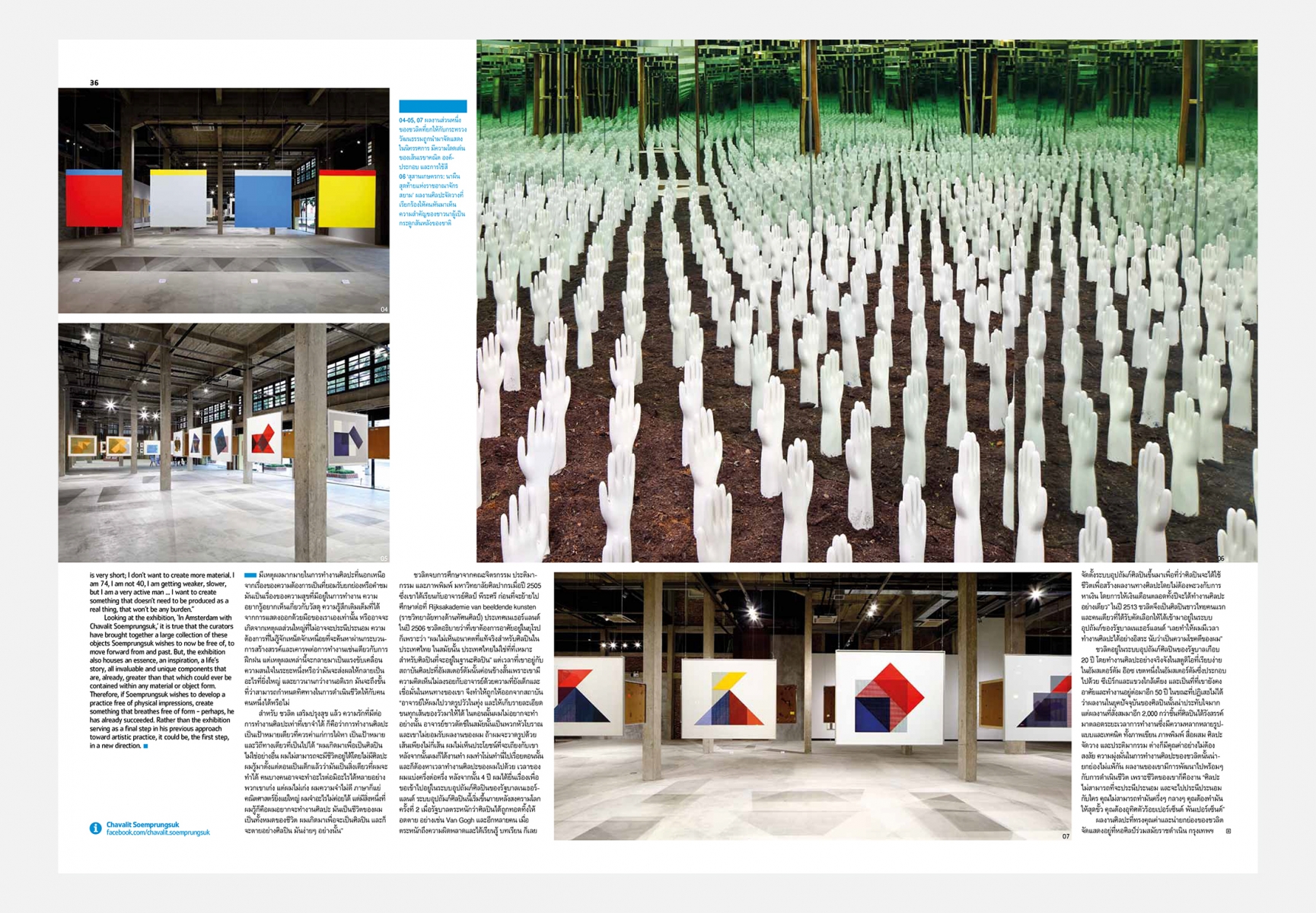

How does one present an artist’s lifestyle in the form of an exhibition? The answer is, while difficult to carry out, simple – pack the life up, all the footprints of its path, and exhibit it – all of it. All of Soemprungsuk’s artwork, personal belongings, collected objects and studio space were carefully dismantled, packed, piece-by-piece, and shipped from Amsterdam to Bangkok. Thousands of paintings, hundreds of books, art materials, drafting table, reading chair, sketchbooks, mementos, and notes – everything goes. The exhibition contents were then carefully unpacked and reconstructed within the art venue exactly as they were. When one walks into the RCAC, they will truly find themselves, ‘In Amsterdam, with Chavalit Soemprungsuk.’ “We took everything down, exactly as it was, documented the inventory, and reinstalled it, exactly the same as it was. It is like, when you are outside, you are in Bangkok. When you arrive in the exhibition, you are in Amsterdam. You get the atmosphere exactly how I lived; nothing has changed. Everything, even the scratches on the step where my dog used to run up, everything is how I lived. That is the idea.”

Within the exhibition space, one does feel as if they have found themselves exploring the contents of a stranger’s home while they are out, everything from books left out next to a reading chair and small knick-knacks set here and there create a comfortable clutter that couldn’t be fabricated. But, besides the feeling of being inside an artist’s studio space and home, these objects also create something more. They come together in a manner that creates a framework for the exhibited artworks, some 200 paintings, prints and drawings, sculptures and an installation work, to be held, and supported, within. Unlike a typical retrospective, where works are displayed perhaps chronologically, or in relation to some theme, Soemprungsuk’s works are hung and supported within a space that somehow succeeds in containing the life that composed them. Notes, instrument and composer – paintings, paint and painter – all stand together – everything is there.

Soemprungsuk described that, after the exhibition is over, he intends to continue working, to continue creating, but plans to take on the challenge of developing work that is free from material form. “I have been working hard, and I have made many things. Now, I have a place to keep and preserve these things. And now, my life is very short; I don’t want to create more material. I am 74, I am not 40, I am getting weaker, slower, but I am a very active man … I want to create something that doesn’t need to be produced as a real thing, that won’t be any burden.”

Looking at the exhibition, ‘In Amsterdam with Chavalit Soemprungsuk,’ it is true that the curators have brought together a large collection of these objects Soemprungsuk wishes to now be free of, to move forward from and past. But, the exhibition also houses an essence, an inspiration, a life’s story, all invaluable and unique components that are, already, greater than that which could ever be contained within any material or object form. Therefore, if Soemprungsuk wishes to develop a practice free of physical impressions, create something that breathes free of form – perhaps, he has already succeeded. Rather than the exhibition serving as a final step in his previous approach toward artistic practice, it could be, the first step, in a new direction.

Originally published in art4d No.208 (October, 2013)

fb.com/chavalit.soemprungsukfb.com/ChavalitFestival