EXPLORE THAI MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN THE 20TH CENTURY (WHICH NOW EXISTS ONLY IN THE MEMORY) AND FIND THE ANSWER TO ‘WHAT IS THE VALUE OF ARCHITECTURE?’ IN THE EXHIBITION BY WEERAPOL SINGNOI (FOTO_MOMO)

TEXT: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUL

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Many must still remember one of last year’s most talk-of-the-town incidents, the demolition of Scala Cinema, a long-standing movie theater in Bangkok that had been a part of a lot of people’s memory. Scala being torn down has led to a more widespread discussion and more people are questioning the rate at which architectural landmarks are being demolished in this country, which has become a more frequent occurrence. The criticism extends to issues about Thai society’s realization of the values of these works of architecture, including their powerful contribution to how a city or a country’s history evolves. Similarly, the exhibition ‘Something Was Here’ by FotoMoMo or Weerapon Singnoi, which took place between March 15th and 17th, 2022 at Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), recounts the relationship between modern architecture and the history of Thailand in the 20th Century. For the surviving works of architecture, the exhibition takes viewers to explore the values of architecture and stories surrounding them, and looks into the remains of the buildings that are now gone.

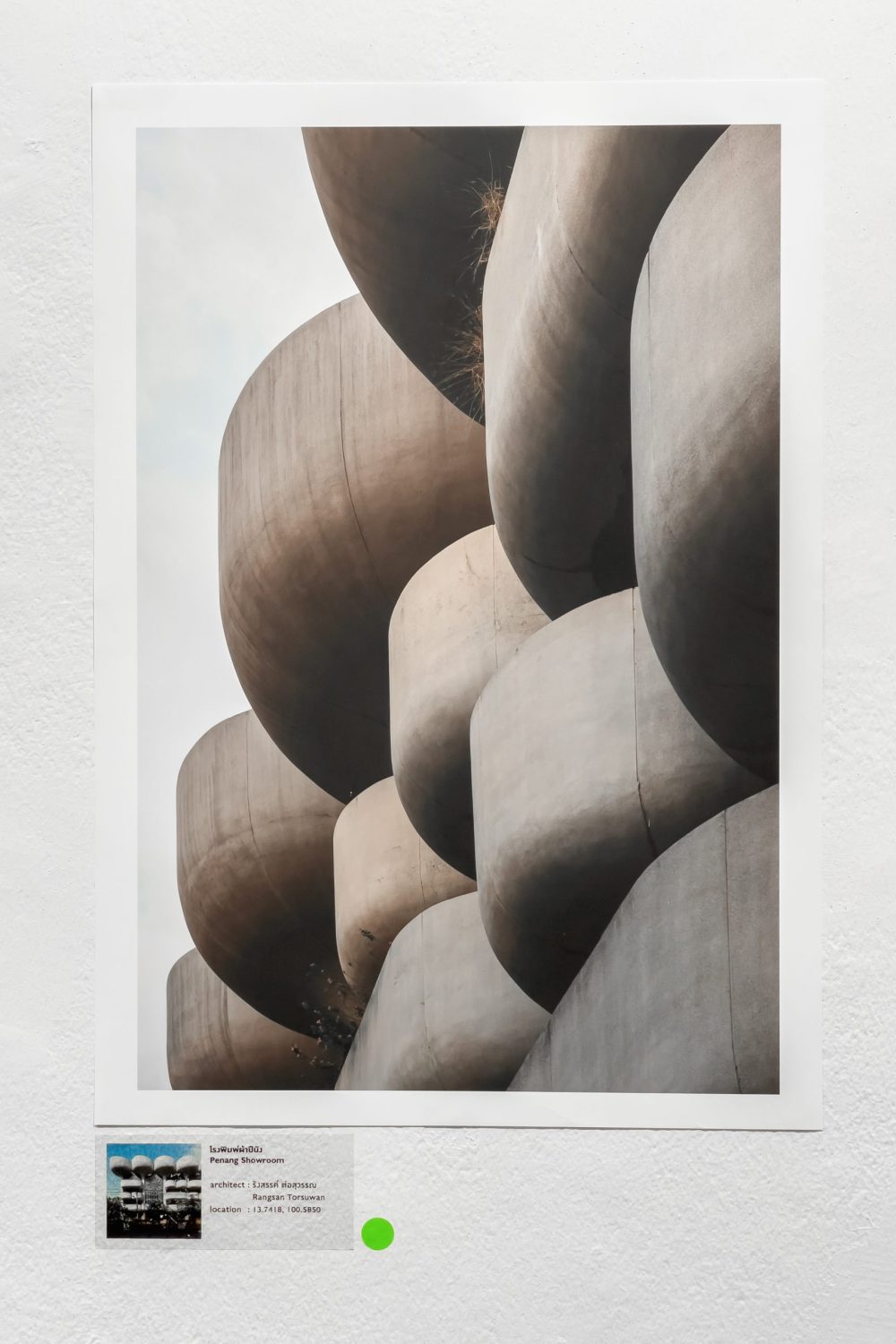

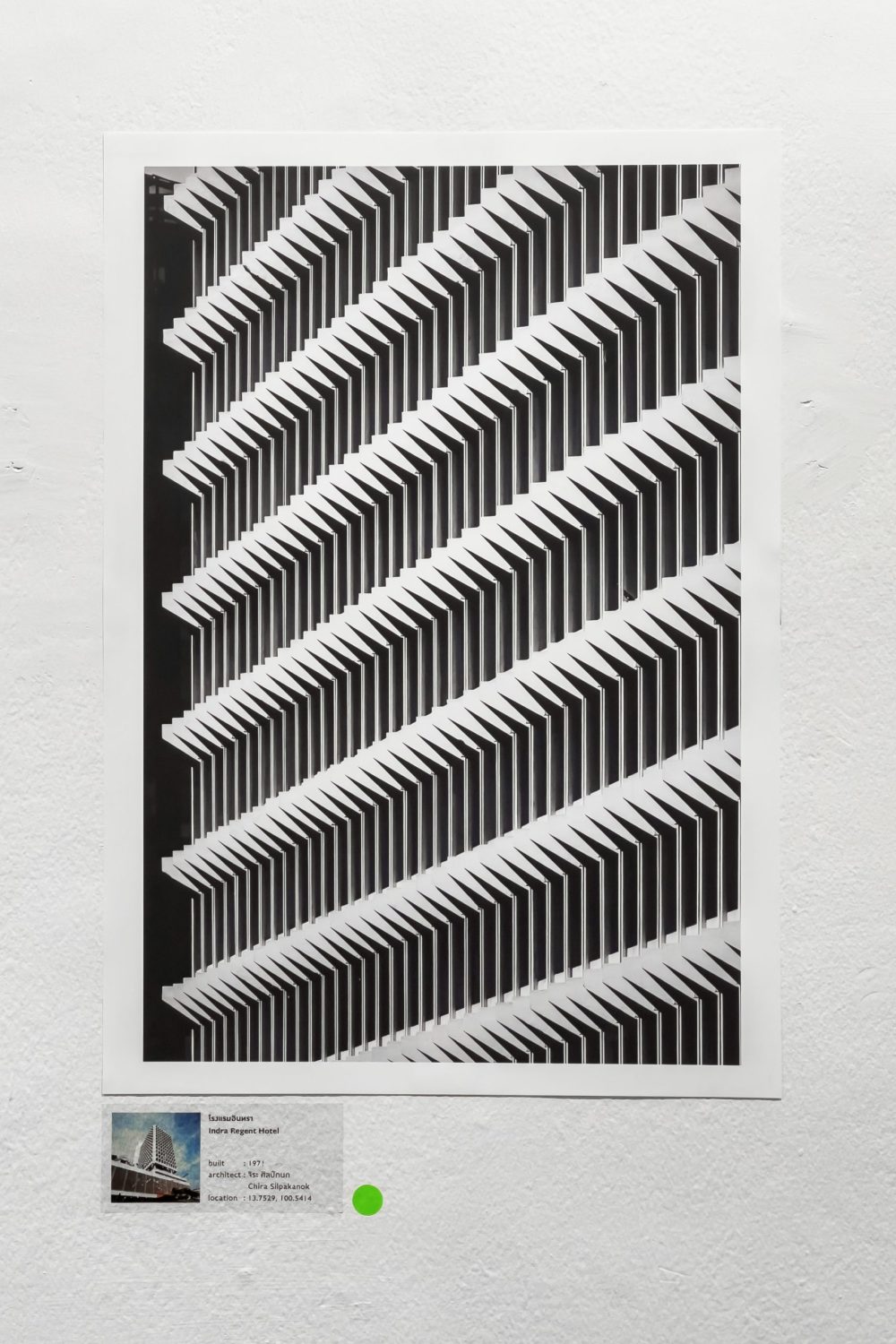

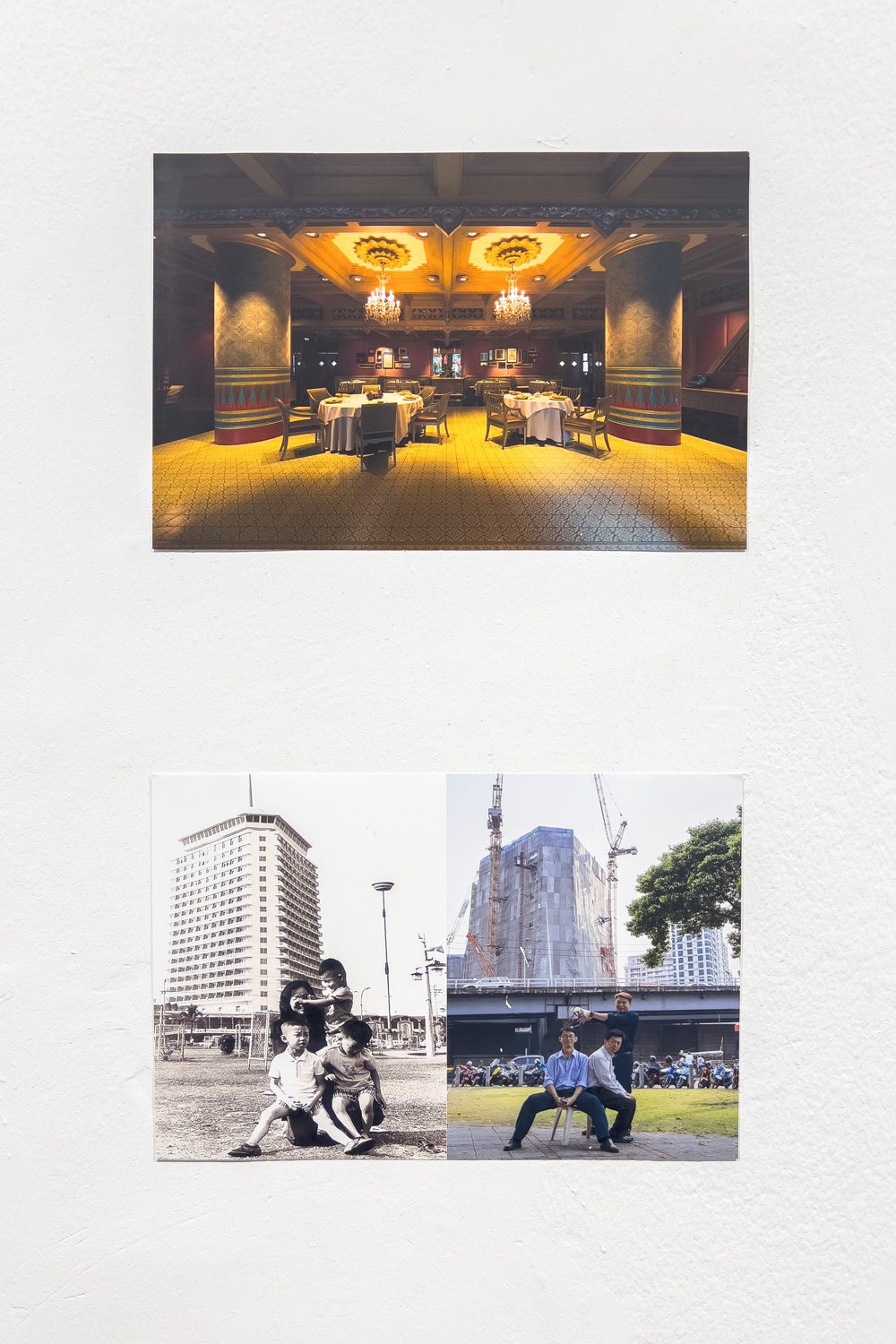

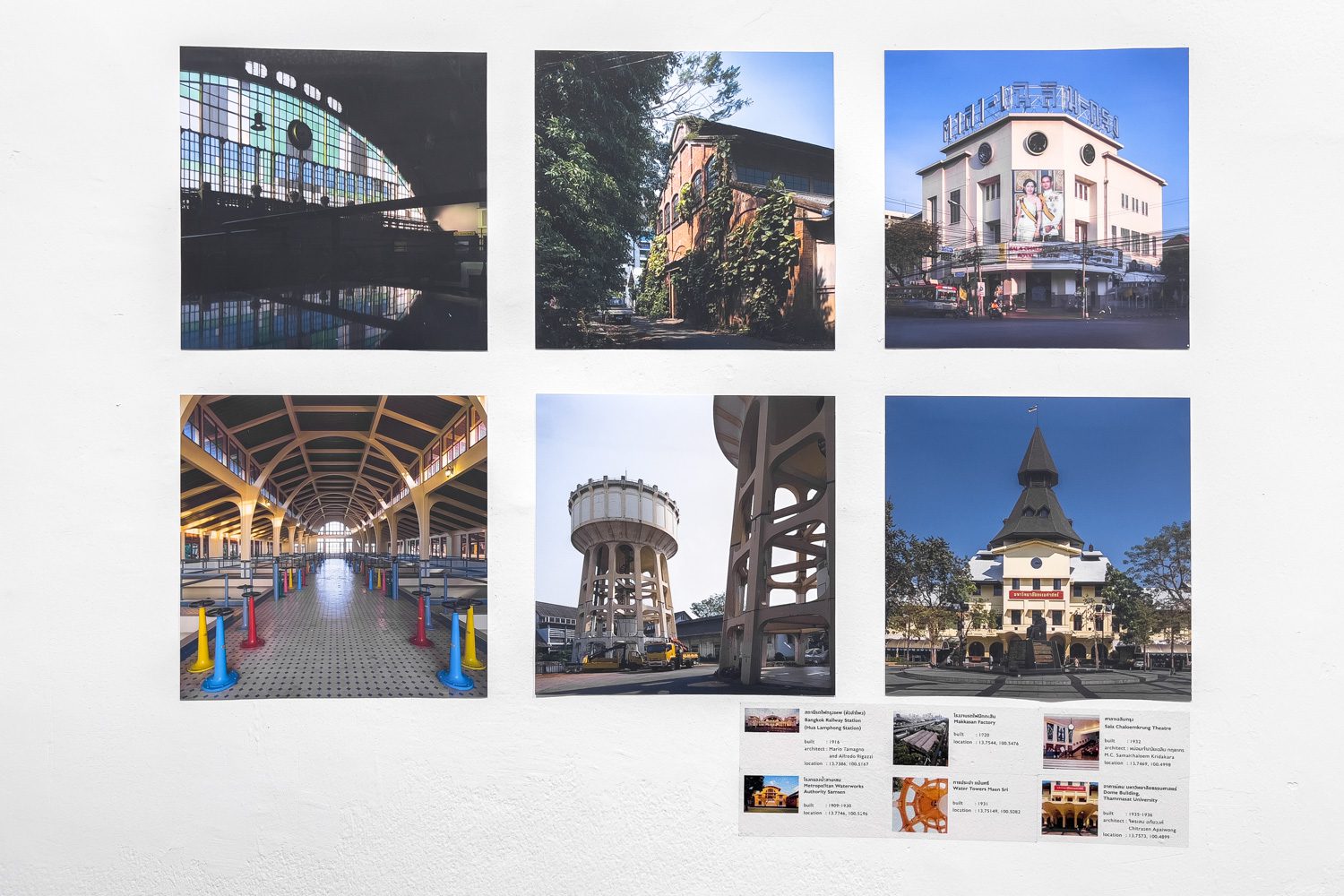

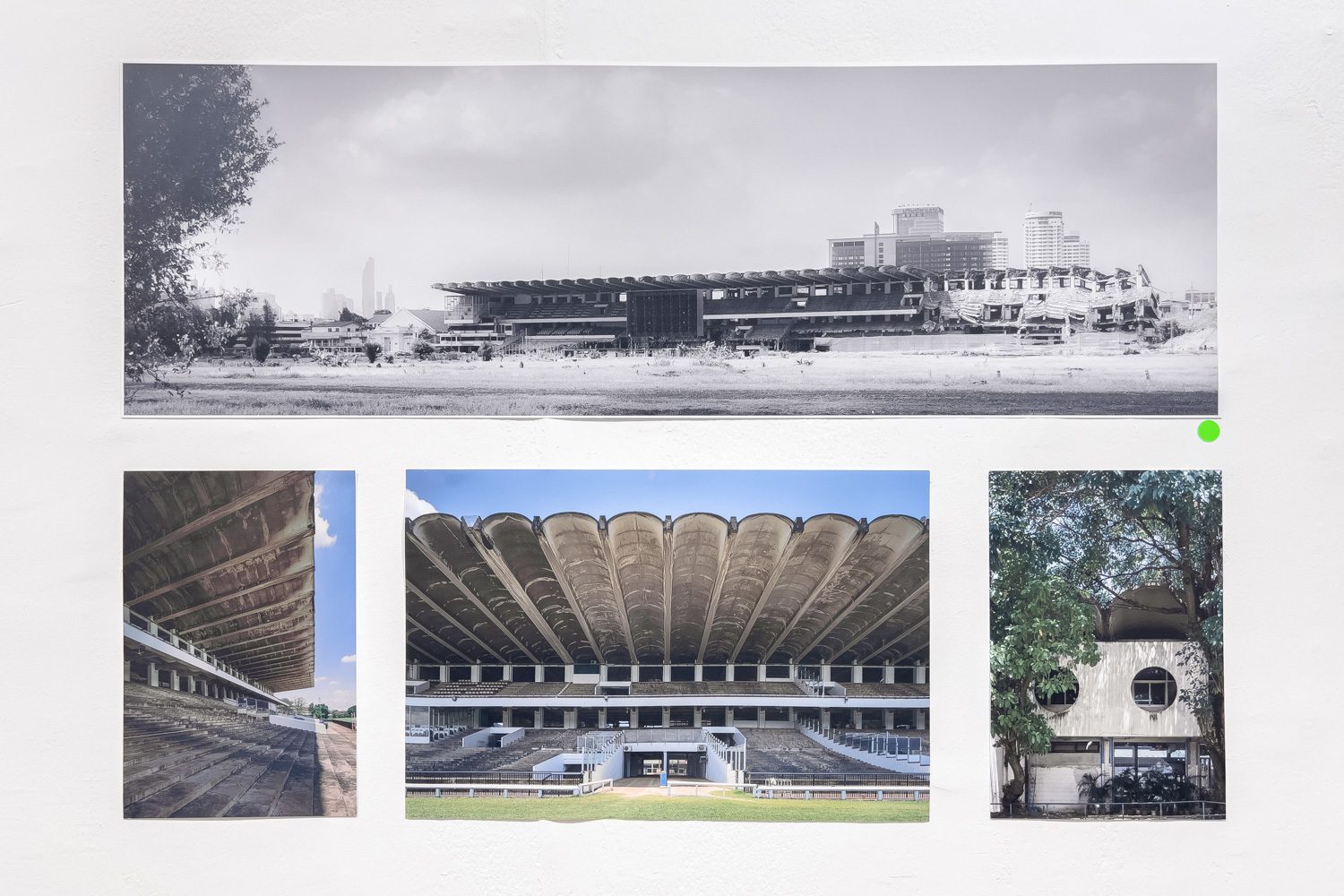

‘Something Was Here’ divides the spiral walkway on the third floor of BACC into two parts. The first part displays photographs of Modernist buildings in Thailand that many are familiar with such as Nightingale-Olympic Department Store (1996), Penang Textile Printing Building (N/A), Holiday Inn Silom Hotel (1970), Indra Hotel (1971). The focus is put on the buildings’ distinctive architectural characteristics from forms to striking concrete facades. These buildings represent Thailand in the global arena in the post-King Rama 5 period when Bangkok saw the birth of high-rise buildings such as Holiday Inn Silom Hotel, Indra Hotel or Nang Lerng Racecourse (1916) with its 40-meter cantilevered roof. These works of architecture helped strengthen Thailand’s image in the ‘western’ standard and perception through their use of advanced construction technologies and materials at the time such as steel, concrete and glass. There were a great number of public utility buildings such as Samsen Water Filtration Facility, the Grand Station (1916) and The Metropolitan Waterworks Authority building (Mansri branch) (1931), all of which tell the story of the foundation of the city’s urban development that would later face an incredible growth in the following decades to come. Interestingly, the exhibition provides descriptions informing viewers the current status of each building, ones that are gone and ones that still exist. Some of the buildings such as Dusit Thani Hotel and Switzerland Embassy were torn down for even their historical significance cannot withstand the power of commercial investment. Meanwhile, there are buildings such as the Supreme Court Building or Nang Lerng Racecourse whose original structures were demolished for reconstruction. The attempt to rebuild these historical works of architecture has many thinking about the intention behind it all, and whether it’s a plan to destroy certain traces of history or even construct a new history.

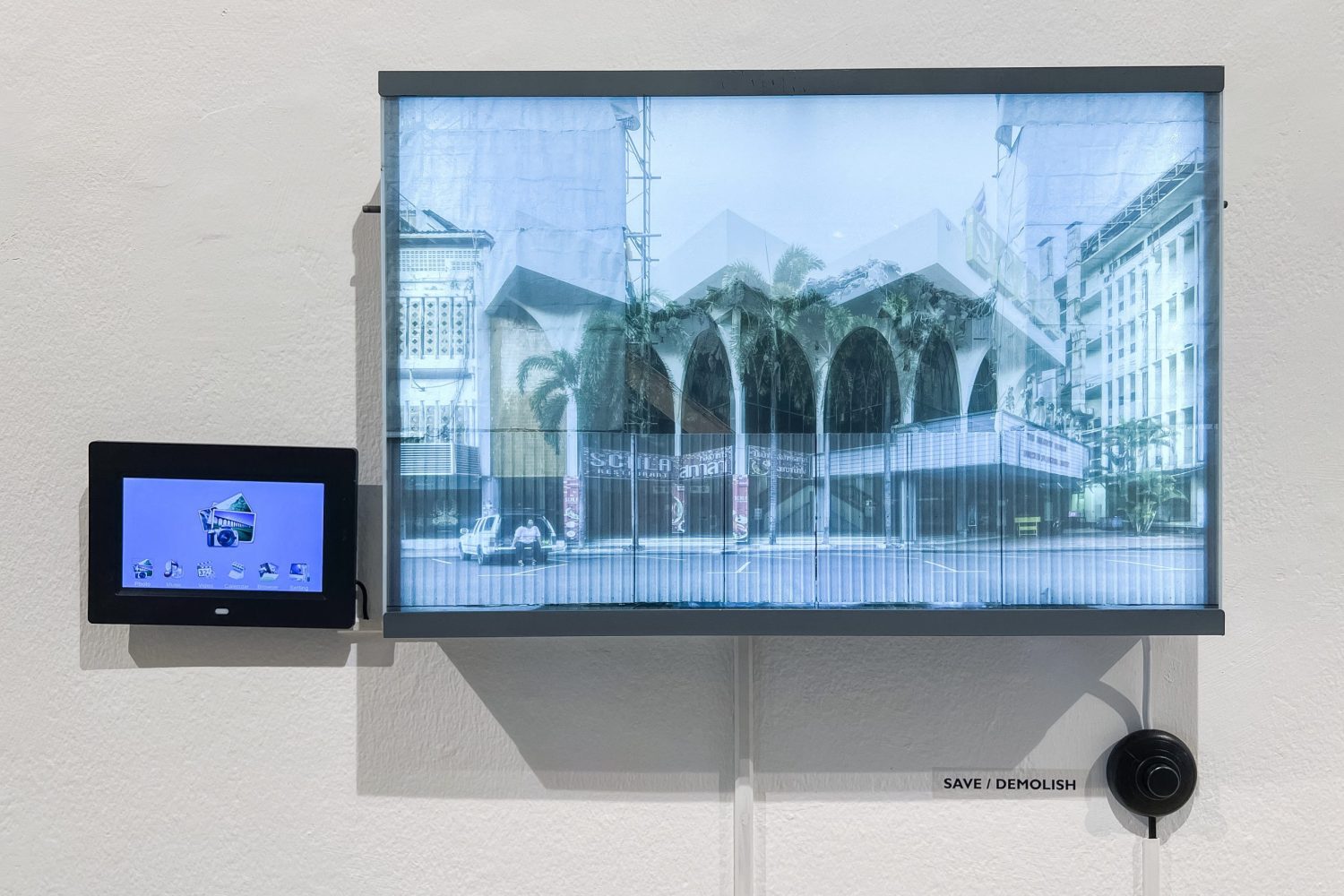

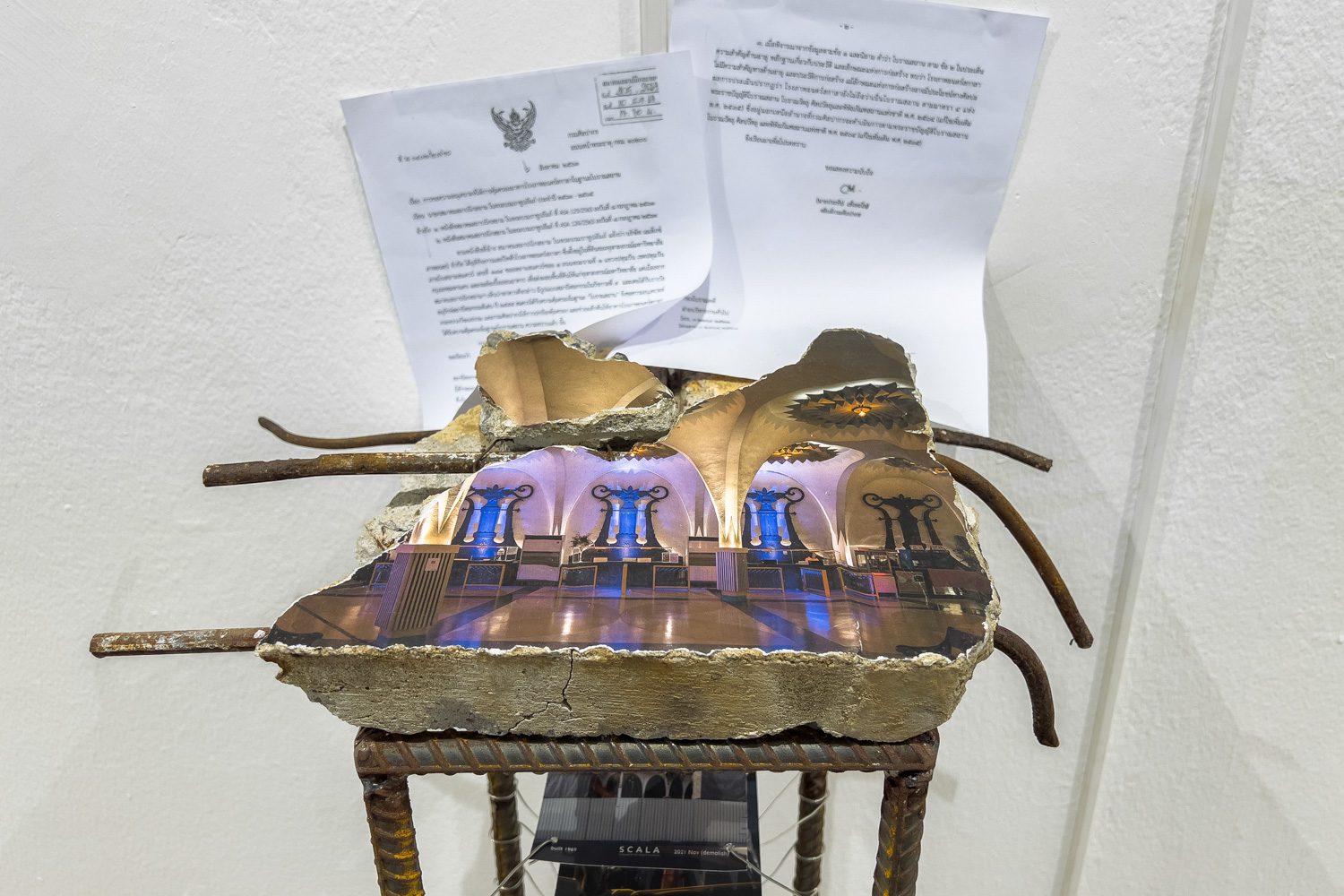

The second part of Something Was Here picks controversial cases such as Dusit Thani Hotel and Scala Cinema, and dives deeper into the stories after the two buildings were wiped out from Bangkok’s urban fabric. For Scala, the architecture that combined the prominent arched concrete columns and Art Deco aesthetic of the ceiling were displayed on the light boxes. At the bottom, buttons were provided for viewers to choose whether to ‘Save’ or ‘Demolish’ the building. If the latter is chosen, Scala’s architecture would be replaced by an image of scaffoldings and construction site, ending its 51-year long history that even the ‘2013 Outstanding Architectural Conservation Award’ couldn’t do anything to help. At the bottom of the light box, the image of piles of broken bricks, concrete debris and steel pipes was overlaid by the image of Scala’s beautifully lit interior at night. It depicted what feels like an inevitable ending in the cycle of life of architecture. A building that was once loved by many and appreciated for its architectural values could not escape its final stage and ended up becoming only piles of construction wastes that eventually returned back to the ground. The endeavor to stop its great fall was exhibited through an official letter issued by the Association of Siamese Architects to the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts Department, asking for Scala to be protected as a ‘historical site.’

This particular part of the exhibition is straightforward in its message. With Scala now gone, all that is left are a couple of pieces of papers, piles of construction wastes and stories and images in people’s memories.

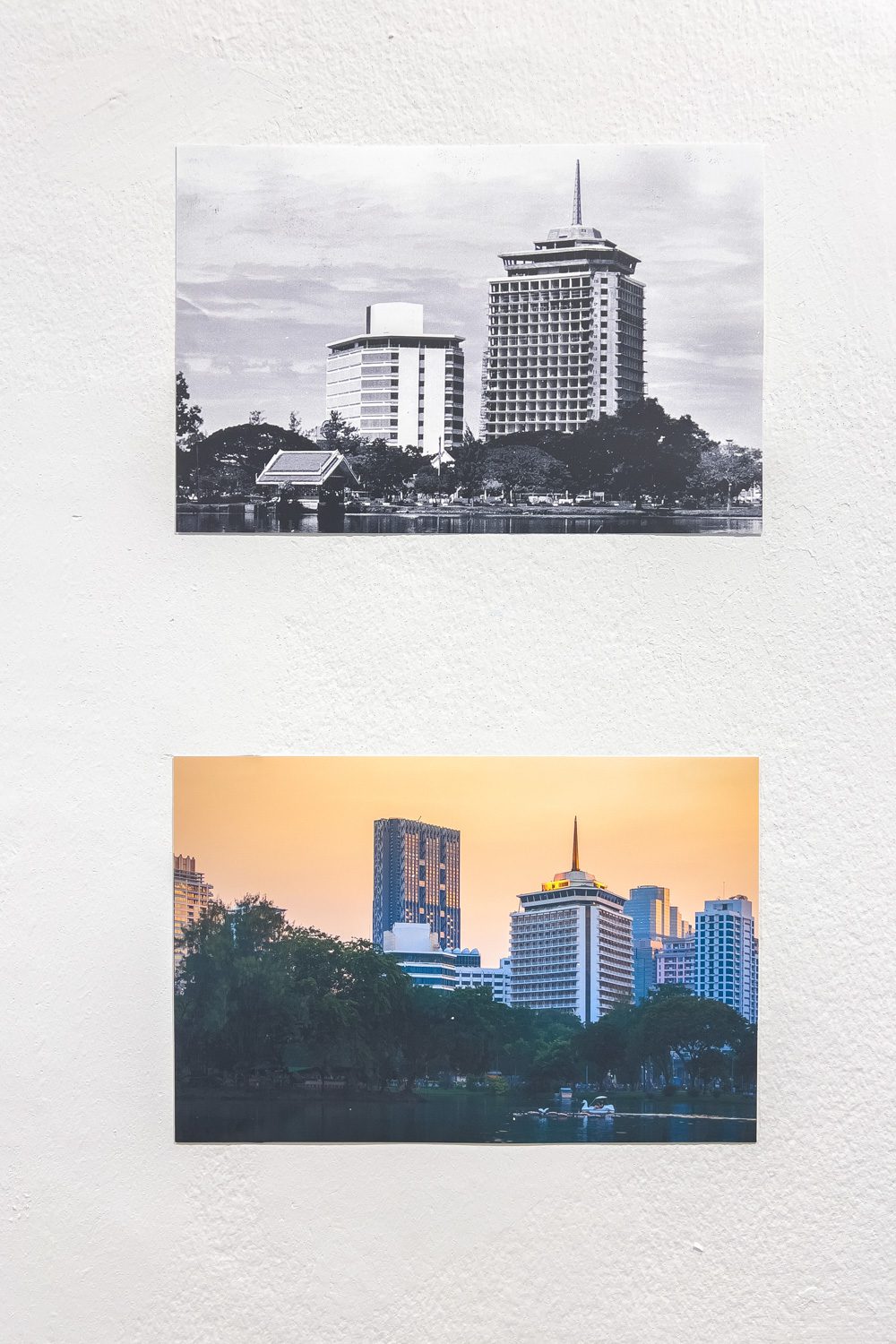

Not too far from Scala, Dusit Thani Hotel Bangkok was facing a similar fate. The demolition process of the iconic, 23-story-high hotel that had been on Saladaeng Road of Silom district of Bangkok was told through a series of photographs displayed in a rotating triangular stand, depicting Dusit Thani Bangkok in its glory days, with beautiful illumination accentuating the golden spire. The structure was gradually being torn down from the uppermost part. The last photograph captures the building with only the lower half of its structure remaining, reminding viewers of Dusit Thani’s story and pride as once the country’s tallest building. Nearby, another set of photographs was shown, reminiscing memories that people have with the building, from important guests from foreign lands to a family who once visited and took a picture with Dusit Thani as the background. Time passes and another photo taken at the same corner portrays changes of both people and the architecture. Children grow up, adults get older, and the building that was once a landmark of Bangkok is now left with nothing but its corporate logo.

As mentioned earlier, architecture leaves behind memories for people of all social statuses, one way or the other. We refer to people’s collective memories as historical stories. But once those stories get narrowed down to something people relate to at a personal level, they become a connection. There is a story I would like to revisit. Around four years ago when Scala Cinema was still up and running, I remember going there to see the film Logan (2017), the prequel of the superhero character that many have come to know and love. I had no clue that seeing that movie would be the last memory I had with Scala. Walking past the place where Scala once was, I see a space, but the connection I had with it is all gone. The cool, air-conditioned lobby, the ticketing officers and the yellow top of their uniforms, the memories of the films I saw there, everything is fading away. It was at that moment when I finally understood that memories are like a locket with two compartments. We hold one of the compartments and the place holds the other. I think that is why we feel sad when a part of our memory is taken away with no chance of ever coming back.

The exhibition is over. Just like how many of the buildings whose stories it told are now gone. Time continues to move forward. What remains is only the question about the value of modernist architecture in Thailand and how they have become something that store both collective and personal memories for many people. The exhibition asks us to imagine better ways to preserve architecture rather than demolishing buildings, making them disappear and unsalvageable. Something can never be forgotten just because it is taken away or made to disappear. If anything, the disappearance only makes the connection even clearer in one’s memory.