THE INTEREST IN THAILAND’S INDEPENDENT COMIC LED NICOLAS VERSTAPPEN TO DIG DEEP INTO THE HISTORY OF THAILAND’S COMIC AND EVENTUALLY RESULT IN THE BOOK THAT CHARTS THAILAND’S COMIC CHRONICLE OF THE PAST 100 YEARS

TEXT: PIYAPONG BHUMICHITRA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

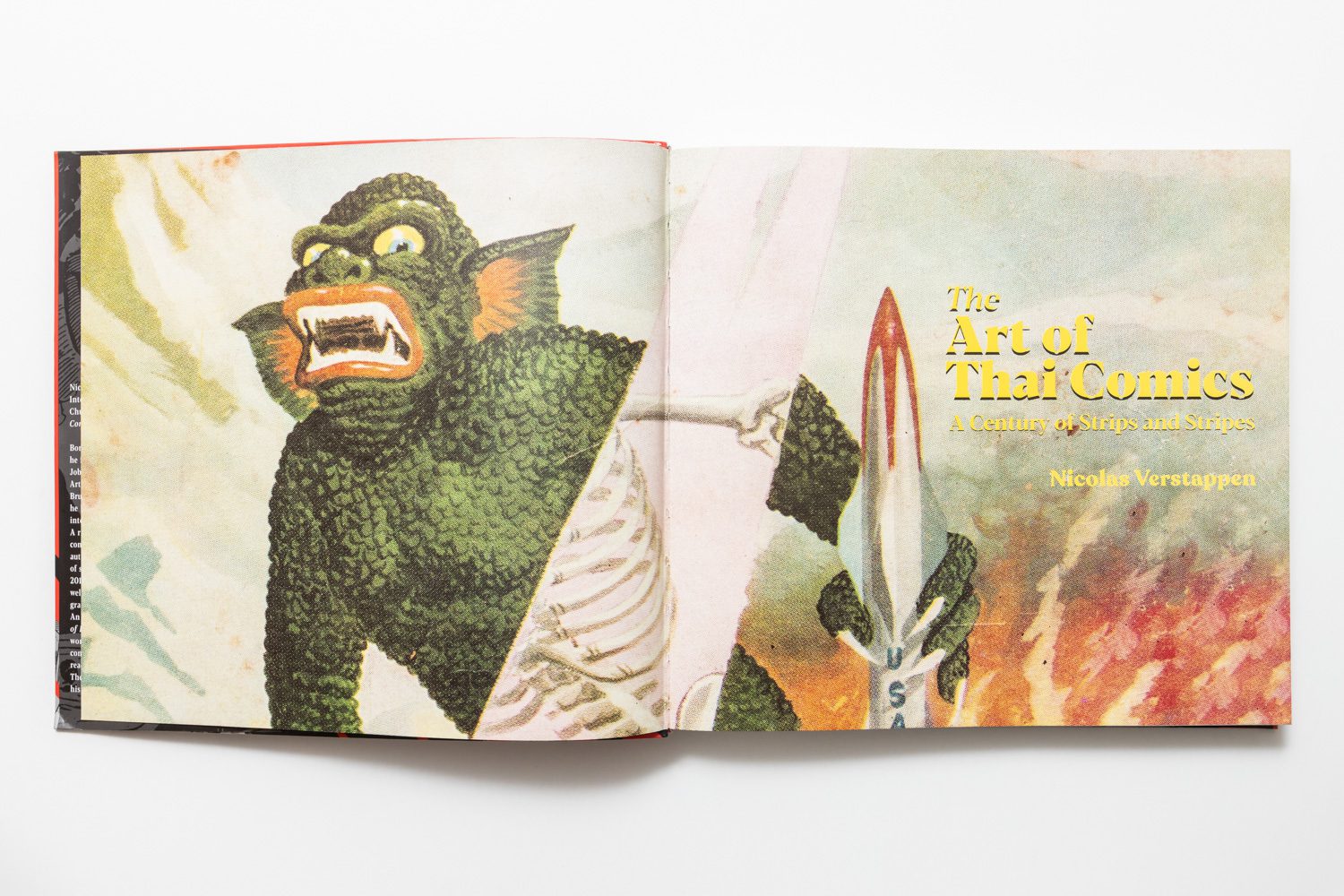

Nicolas Verstappen

River Books, 2021

230 x 250 mm

288 pages

Paperback

ISBN 978-6-164-51036-4

The problem surrounding this book for people who primarily use Thai as their main language, especially during the present state of the economy has almost everyone contemplating their spending habits. The question that would run through their minds are ‘should I get the Thai or English version?’

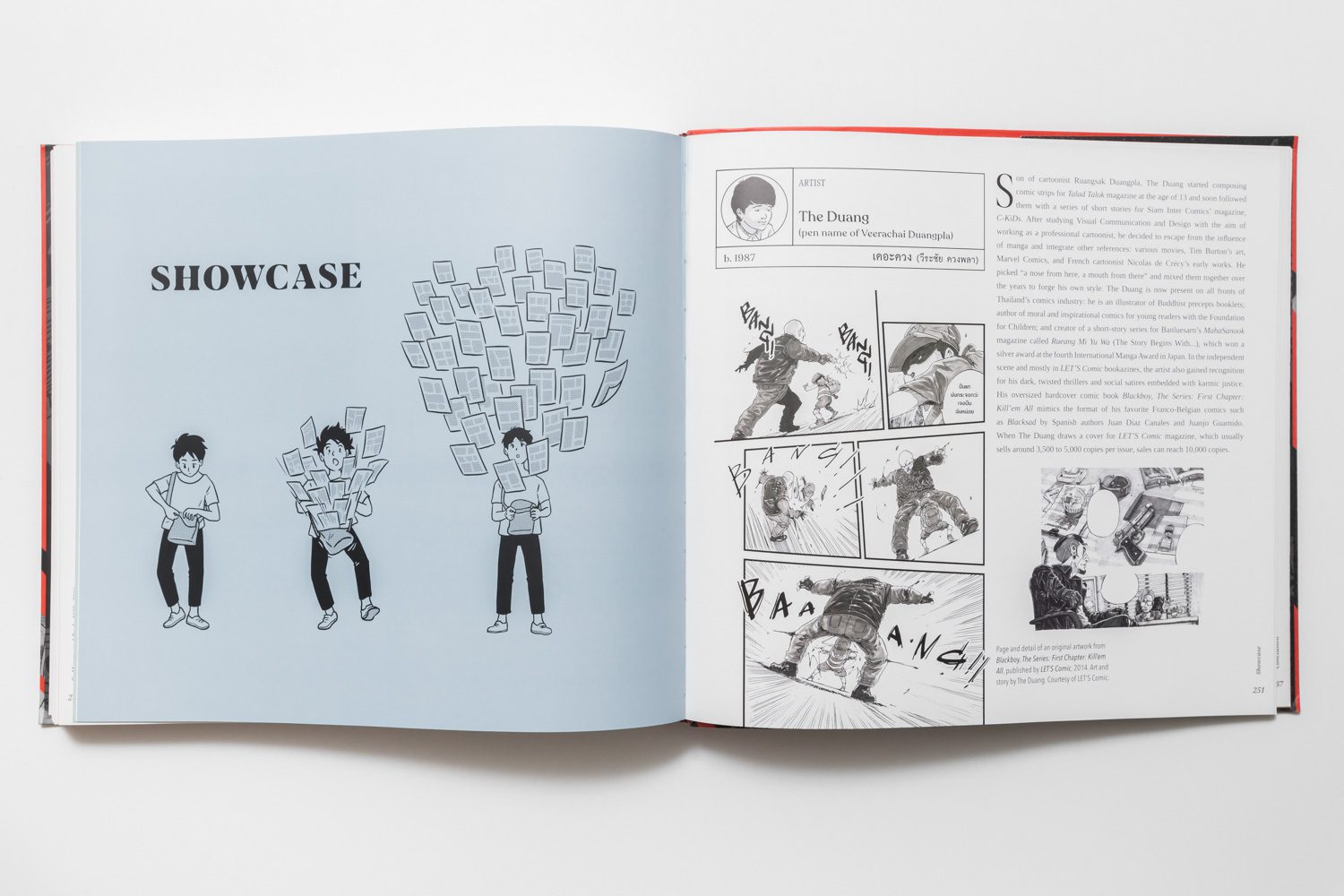

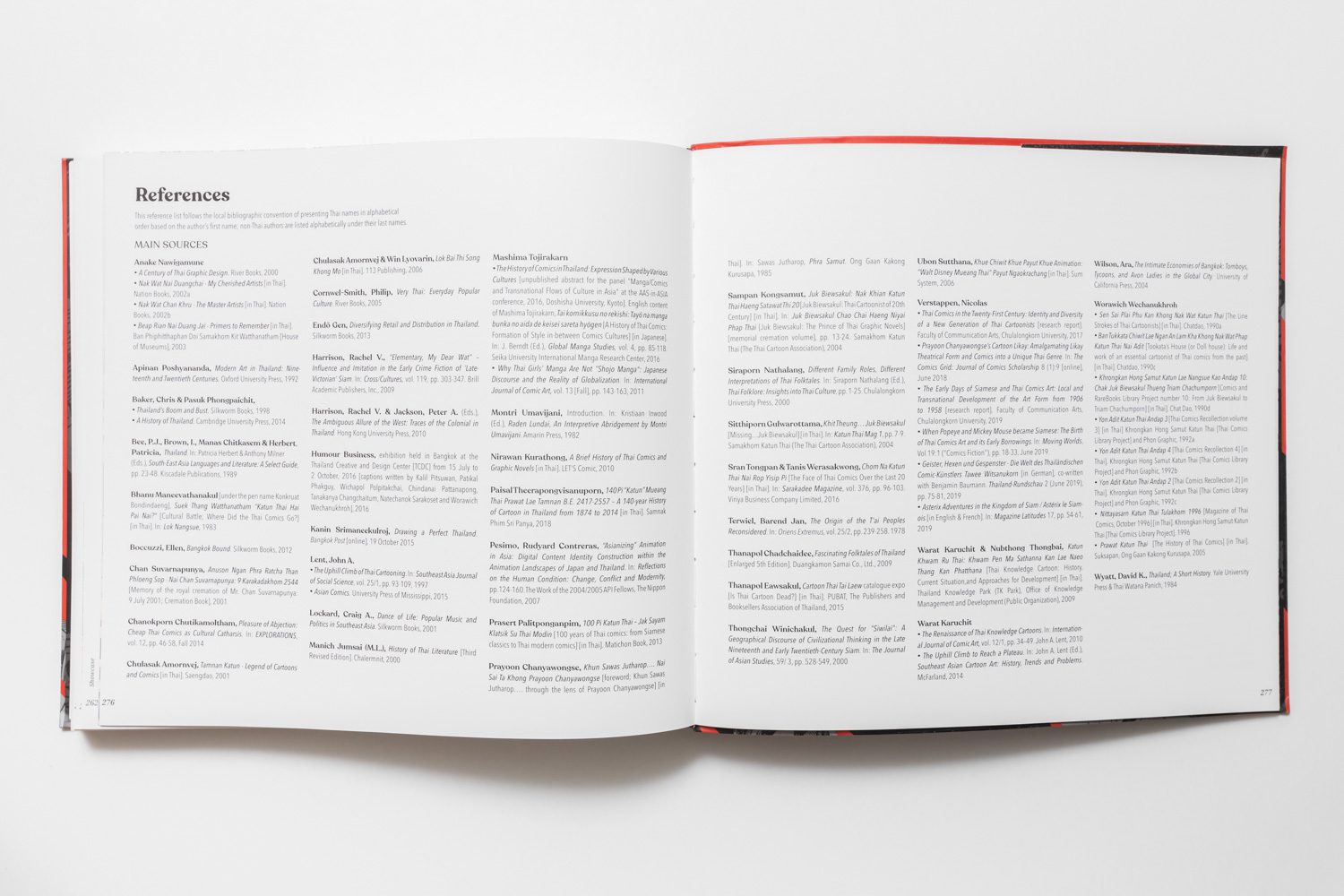

The Art of Thai Comics: A Century of Strips and Stripes is written by Nicolas Verstappen. The book has essentially developed from the author’s one-year long-research project titled Thai Comics in the 21st Century: Diversity and Identity of the New Generation of Thai Cartoonists.

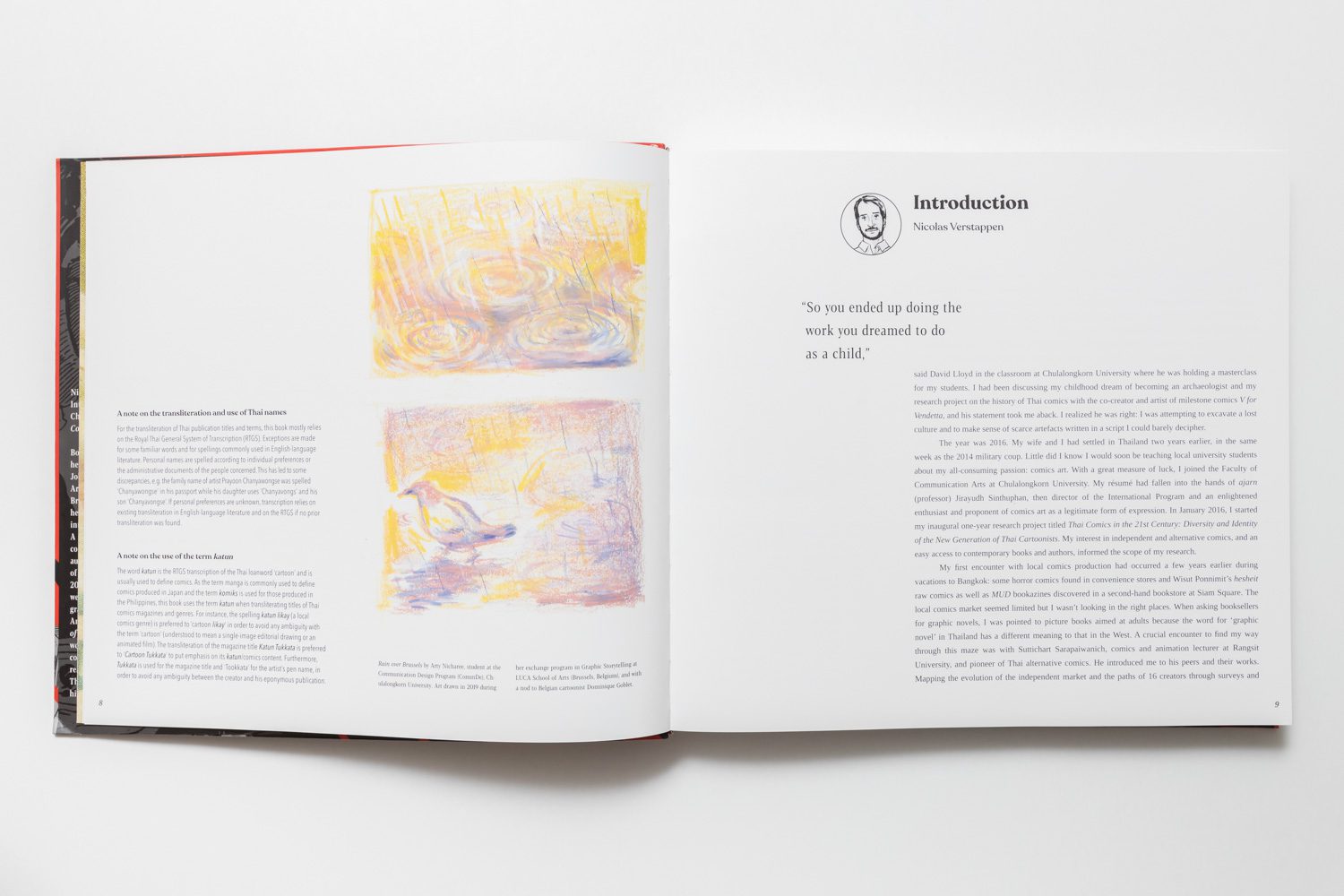

Nicolas Verstappen was born in Belgium. After earning his degree in Art History and Film Writing from Université Libre de Bruxelles, and working for a comic book store called Miti BD, he began creating his own Zine named XeroXed, which complies interviews of alternative comic artists from around the world. Nicolas himself was a in-house comic artist for Beaux Arts Magazine and was also once studying and conducting research on comics as a language that displayed the symptoms related to humans’ emotional traumas.

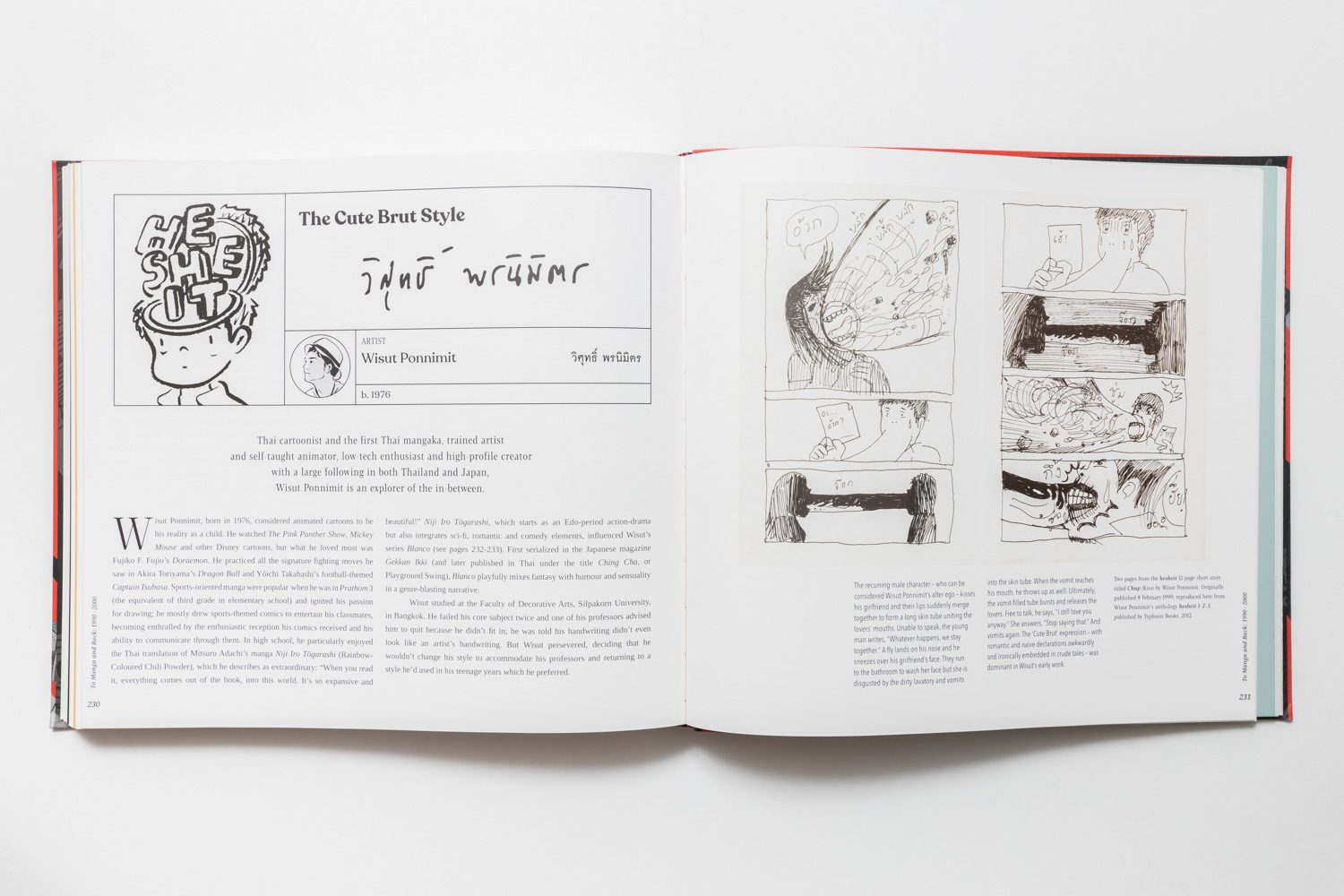

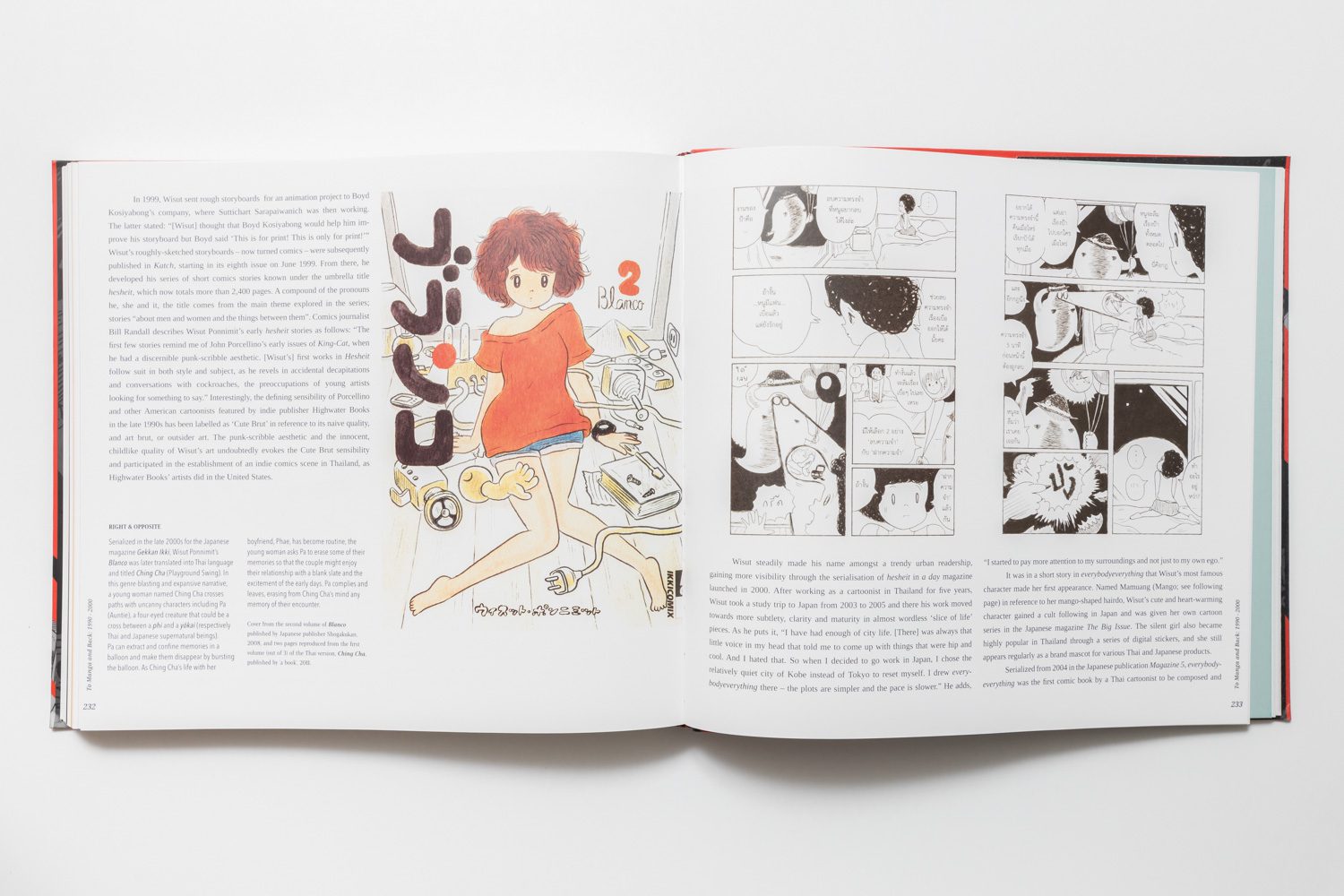

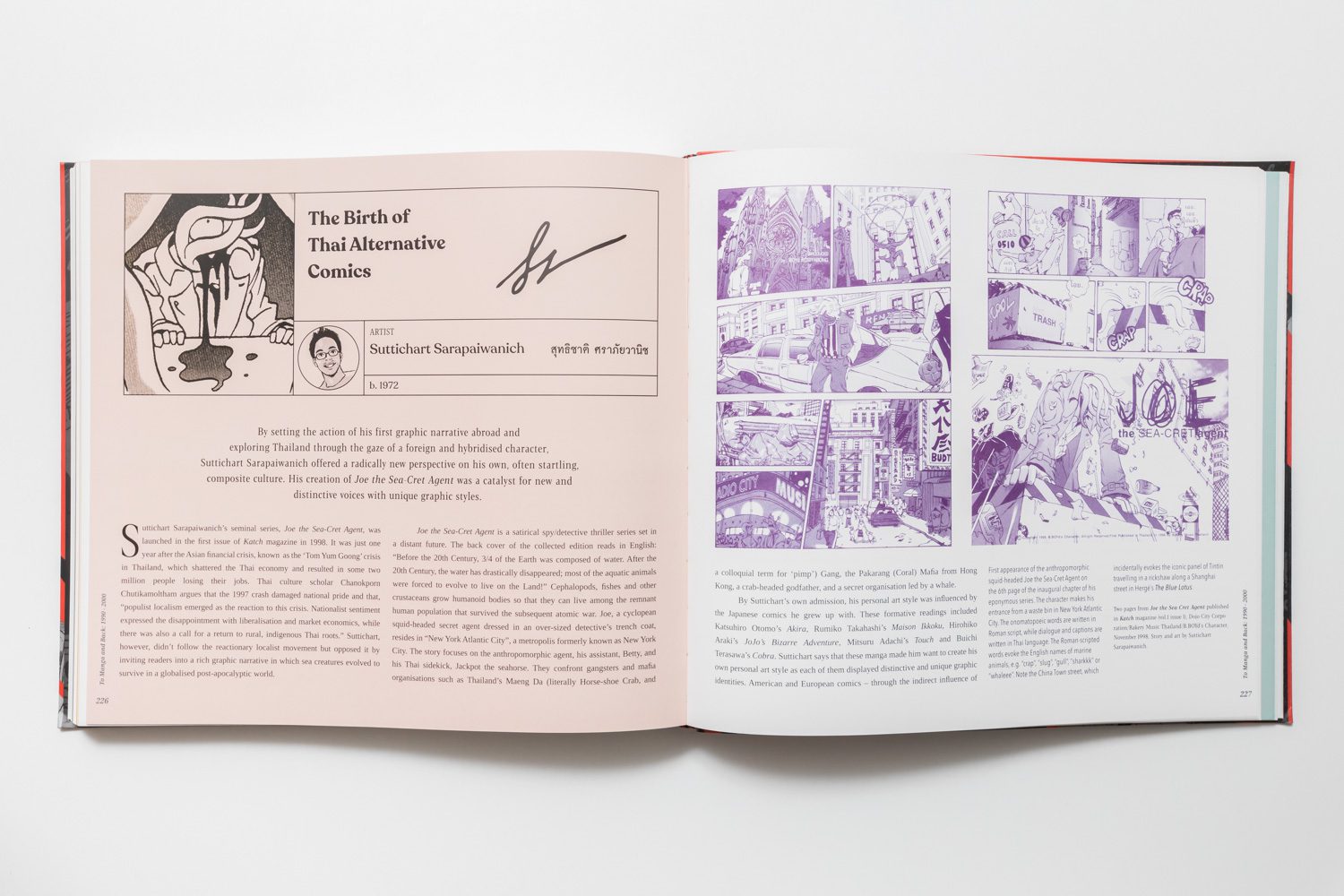

Nicolas and his wife moved to Thailand in 2014. Although it was a couple of years earlier during his visit in the country, when he came across Thai comic books for the first time. It was a horror comic book sold at a convenient store. Then he found hesheit by Wisut Phonnimit, and MUD Magazine, a pocketbook-sized publication that featured a bunch of illustrations, cartoons and subcultures from a secondhand bookshop in Siam Square. He later became personally acquainted with Sutthichart Saraphaiwanich, the creator of Joe the Squid Head and a professor teaching comic and animation at Rangsit University. Through Sutthichart, Nicholas was introduced to other fellow independent comic artists and their works.

His interest in Thailand’s independent comic scene grew into a research project and led him to take the role of an archeological researcher who later wrote and completed this academic textbook. Nicholas discovered that the rainy and humid weather of Thailand’s tropical climate, including flooding, which happens too often for it to be called seasonal, and the book worms that like to have a feast on papers, topped with one of the most classic traits of the Thais who are the kind of people who pay little attention to document archiving, all made his search for the comic books that were written and published before 1980 nothing but painful and a struggle. These publications had disappeared from the market, old bookshops as well as from collectors who would buy and sell the books online. In the past five years, only one comic he was sorting after popped up in the market and along with its super rare status undoubtedly came a price that matched it. Nicholas credited Sutthipoj Wongsisai, a collector and seller of old books whom he has acquainted himself with, as someone who provided and passed on information to him, and enabling him to eventually complete the book.

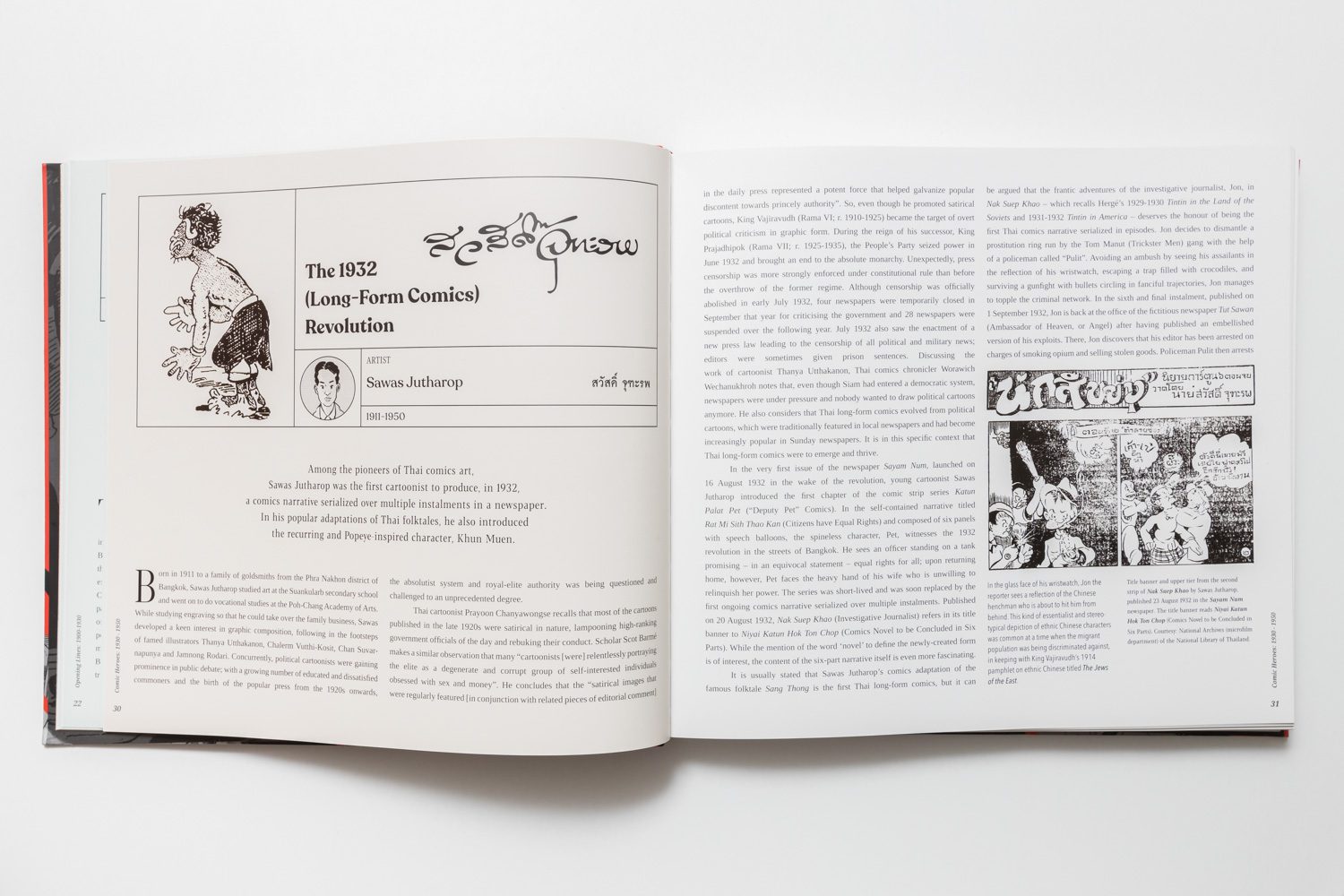

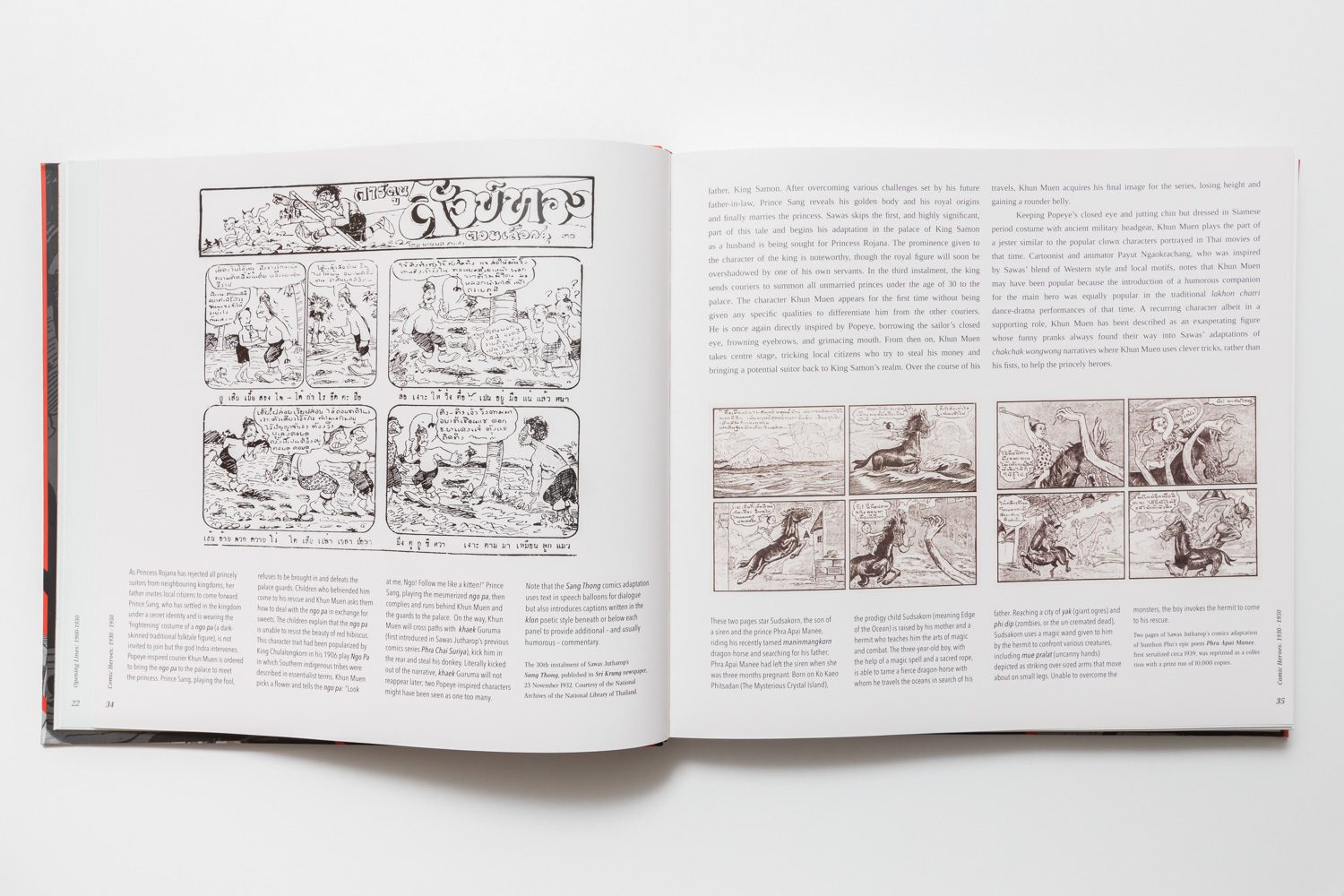

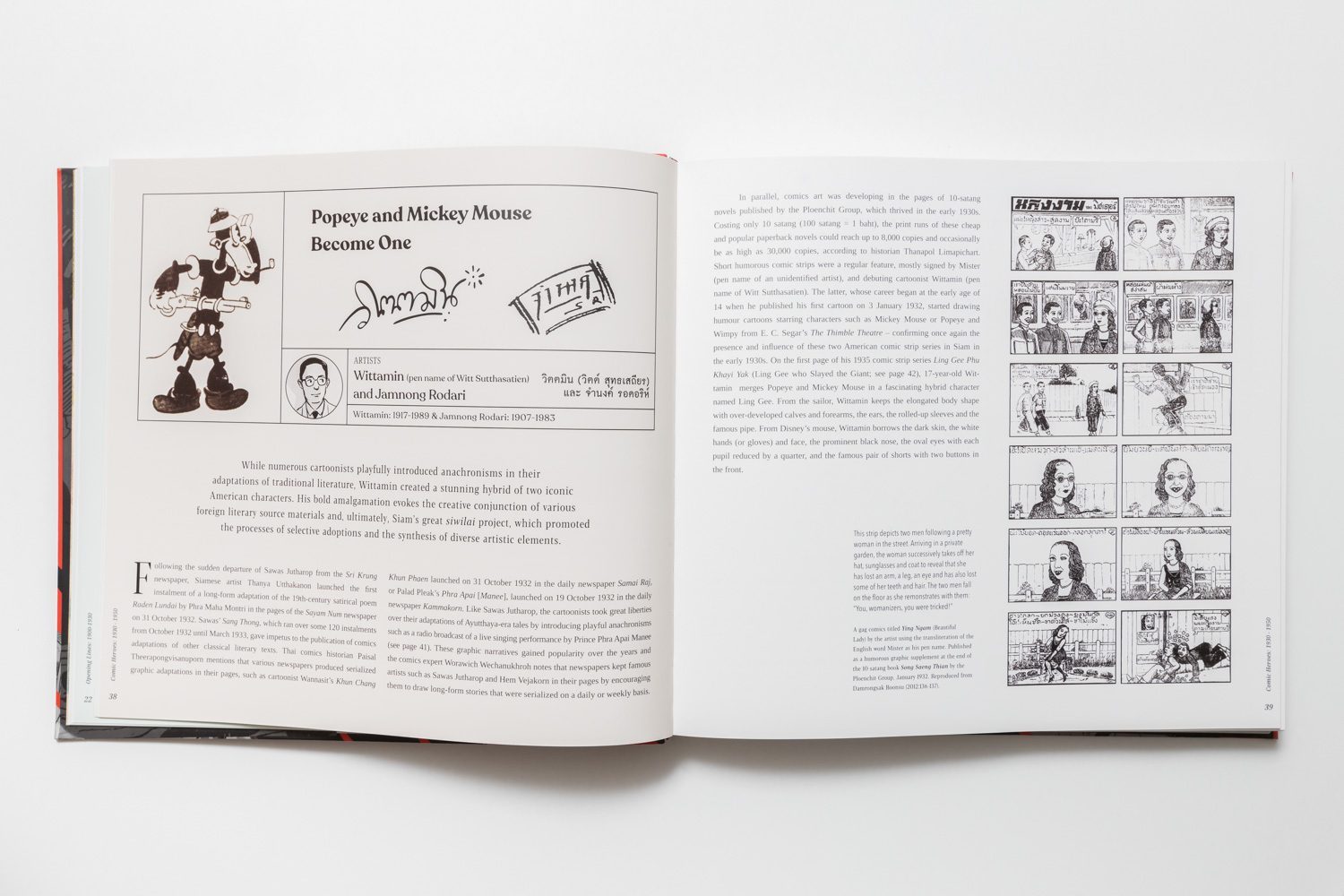

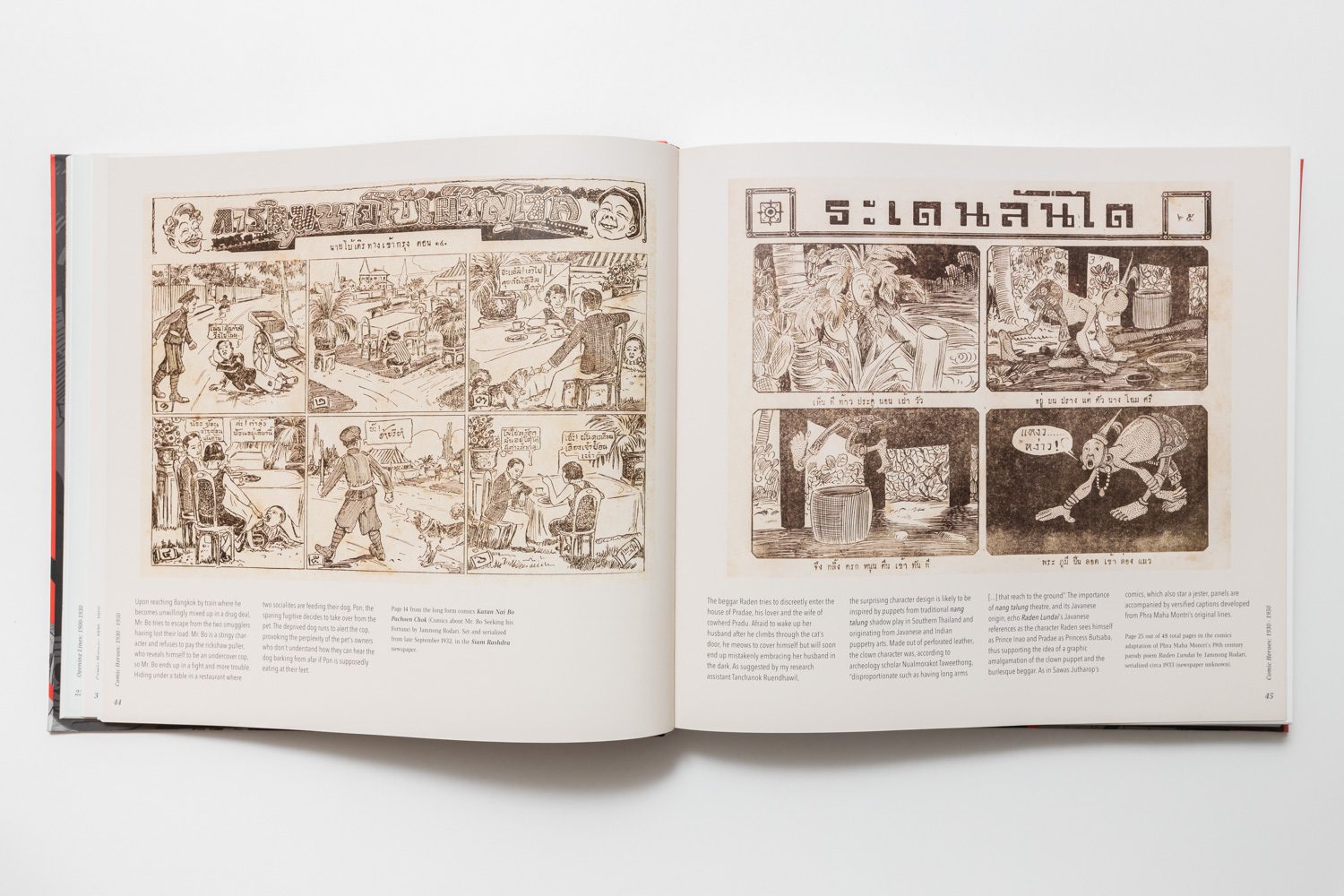

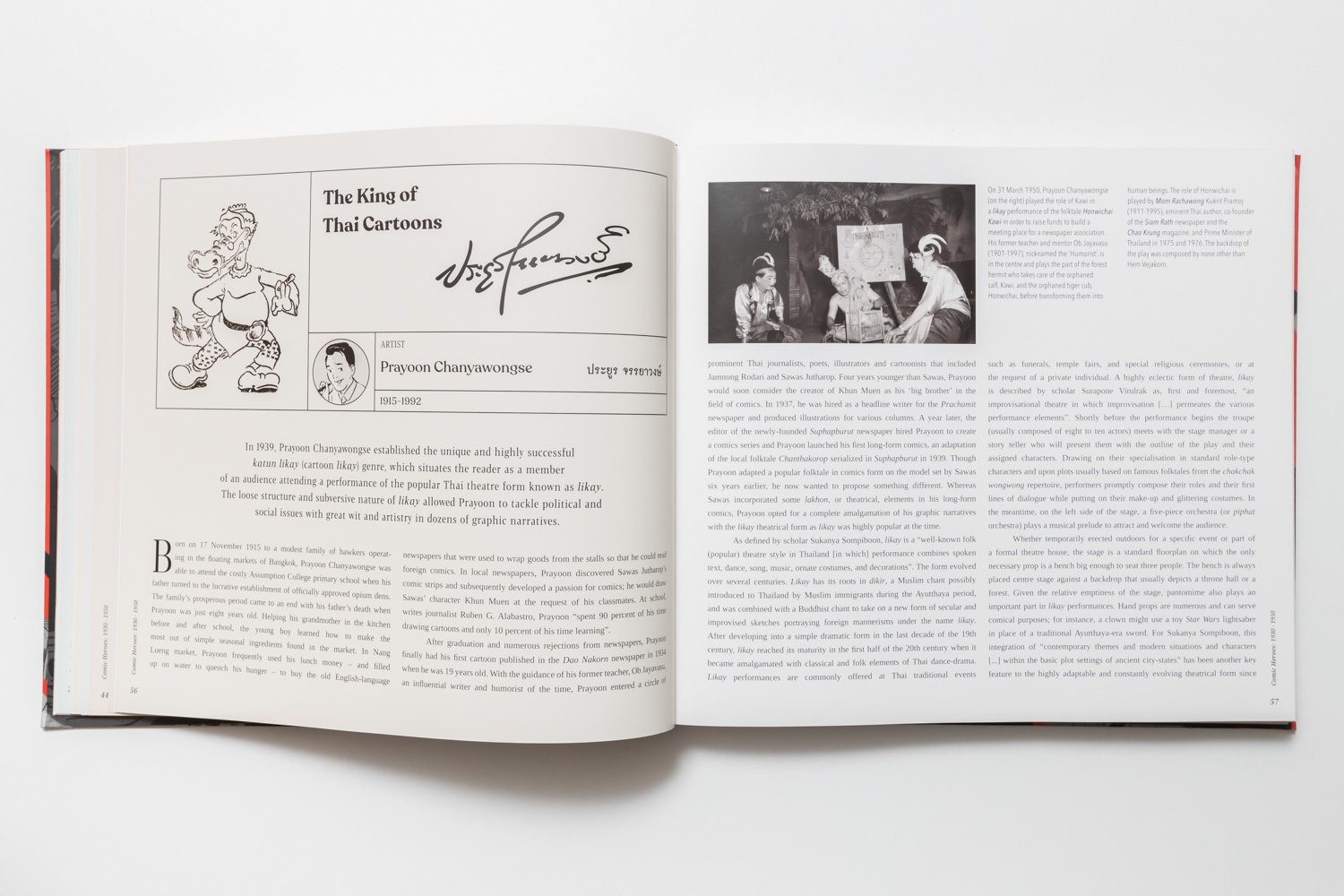

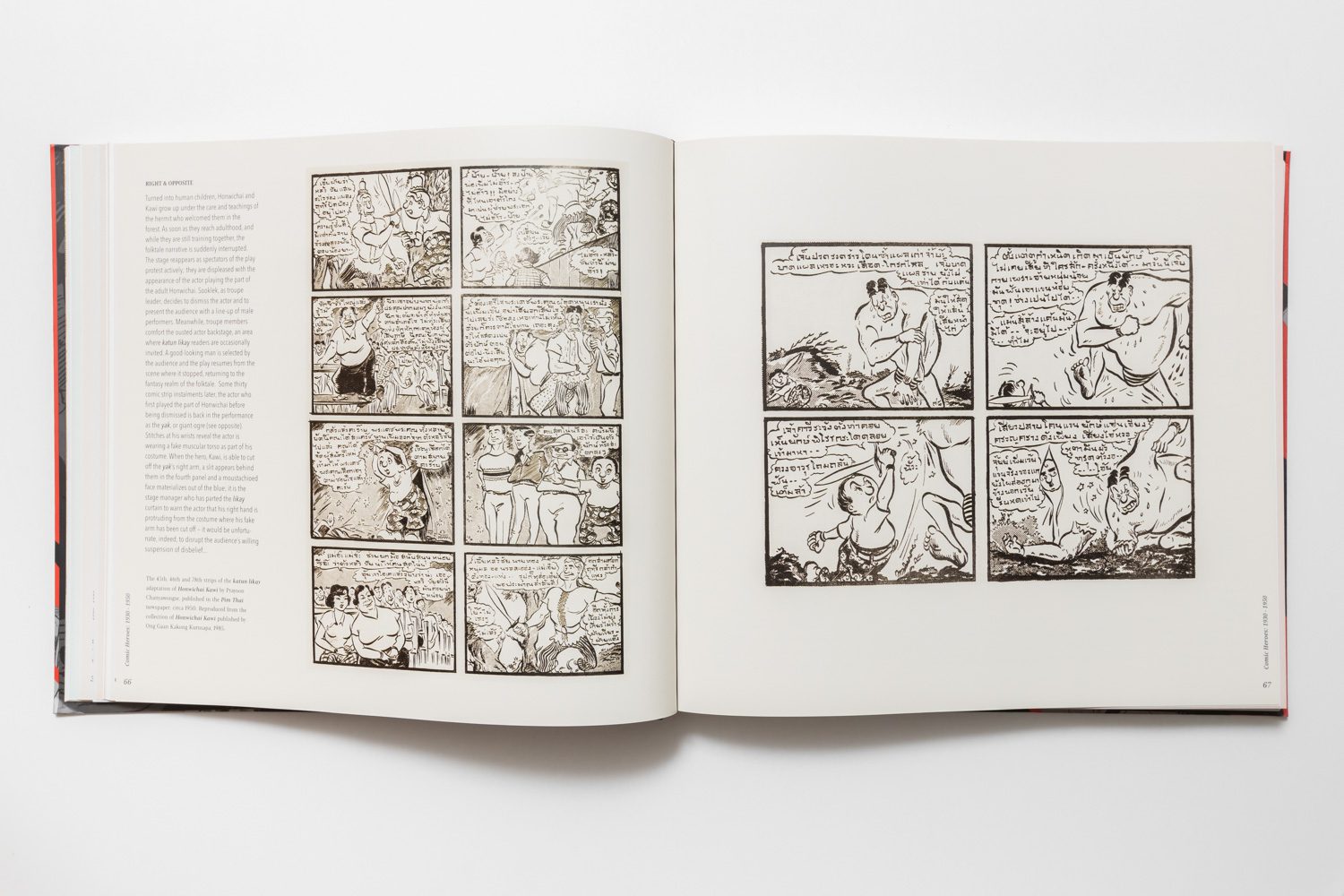

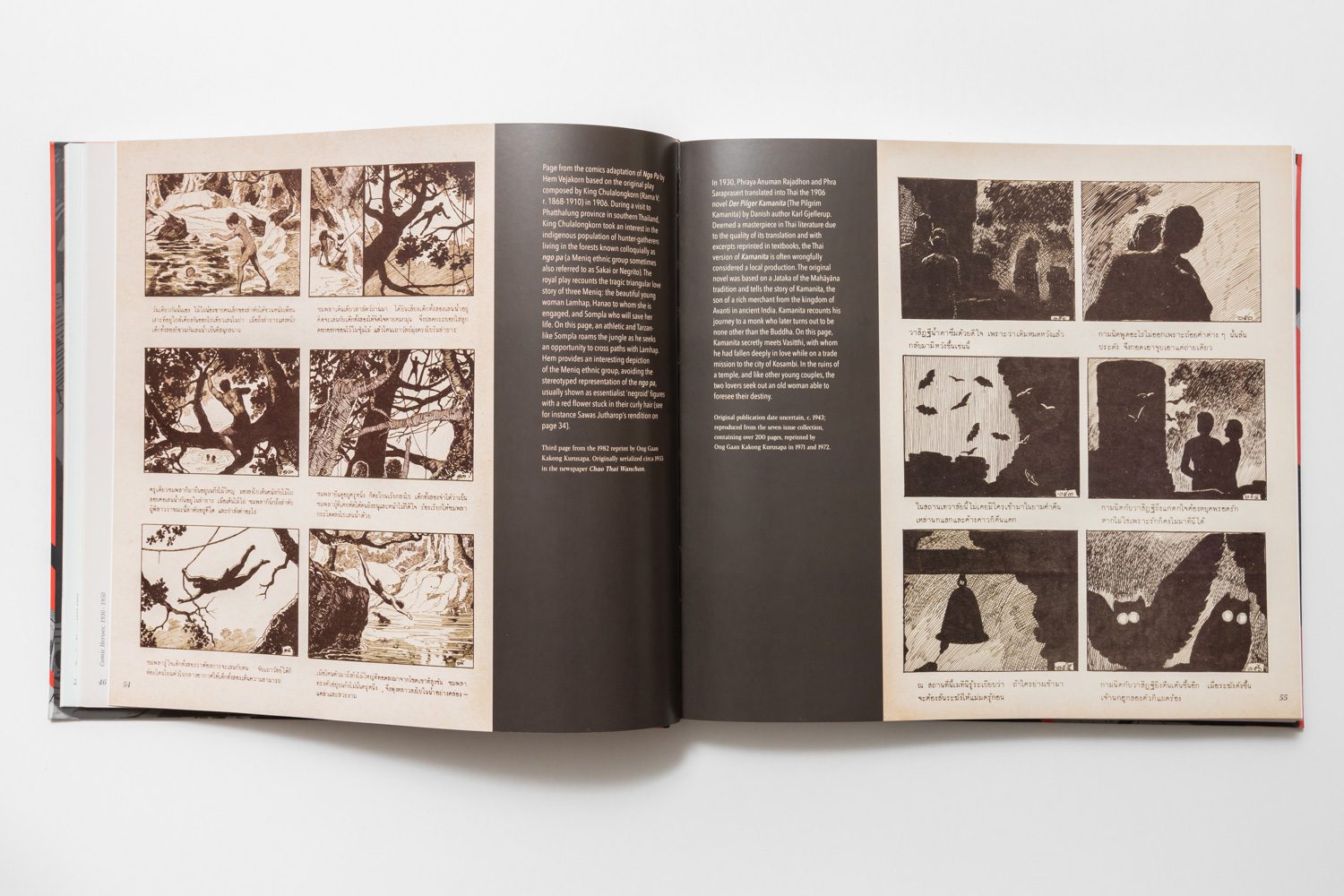

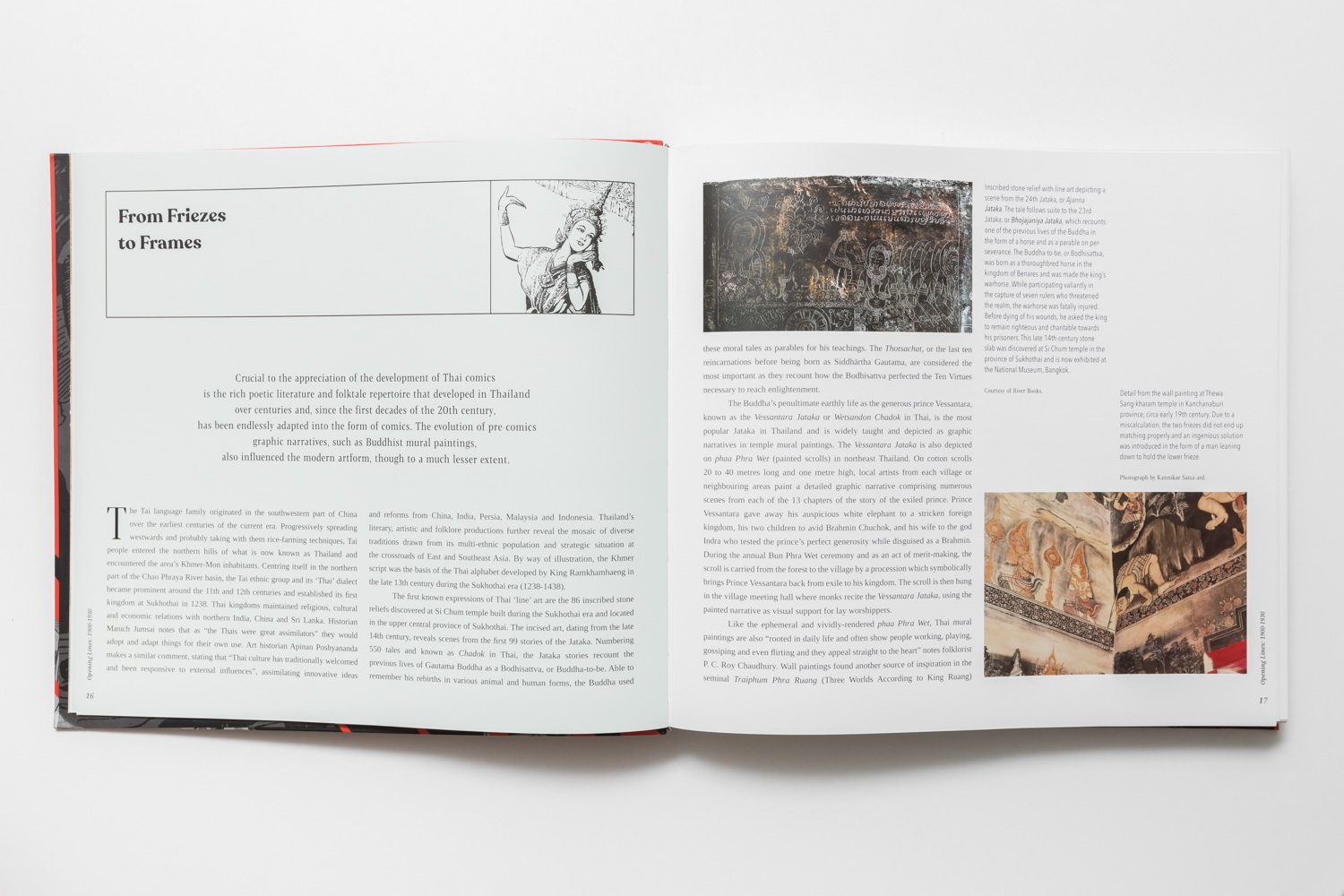

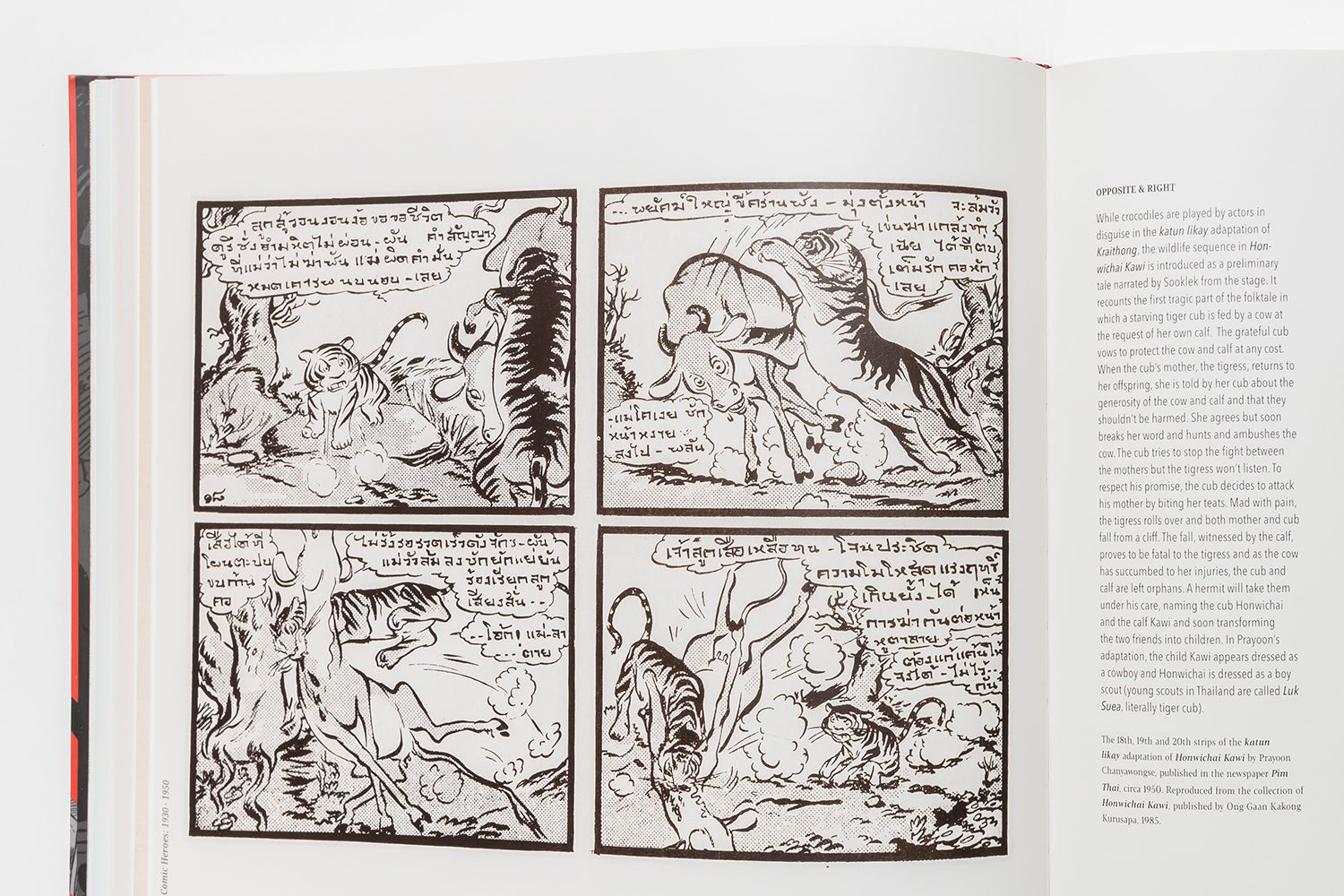

Around March of 2020, Nicholas was able to have access to over a thousand comic strips cut out and collected from Thai newspapers during the 1930s. The collection includes the nearly completed works by Sawat Jutarop and Jamnong Rodari, as well as the early works of Prayoon Chanyawongse and Tookkata, (for your information, none of these works are not kept at the National Archive). This book is the first publication to ever feature the works of Jamnong Rodari, who was one of the most revered comic artists among his peers. Most of his works, however, were lost and the finding led Nicholas to readjust parts of the book to include more stories about these forgotten masterpieces.

With the overwhelming amount of ingredients, achieving the right balance, flow and taste involves not just the author’s storytelling ability but the combined efforts of the Thai and English editor, Sarah Rooney and Narisa Chakrabongse, as well as graphic designer, Peerapat Kittisuwat, who all worked together in order for the book to live up to its ‘A Century of Strips and Stripes’ title. As Nicholas wrote in the introduction, the decision to take out many of the works was part of his determination and intention to showcase the most satisfactory big picture. He wrote that the works were selected based on his personal preferences and tastes as a westerner. It’s very likely that his readers could sense the bias but to be fair, Nicholas also chose works by referencing the admiration and preferences that Thai comic artists and readers have for those works as well.

The decision to feature content that is limited within the span of a century is the author’s own resolution. Nicholas chose to begin at 1907 when a comic strip with a clear storytelling sequence was first published in Siam. He intentionally left out political and humorous comedic comics, which are considered to be a form of Sequential Art.

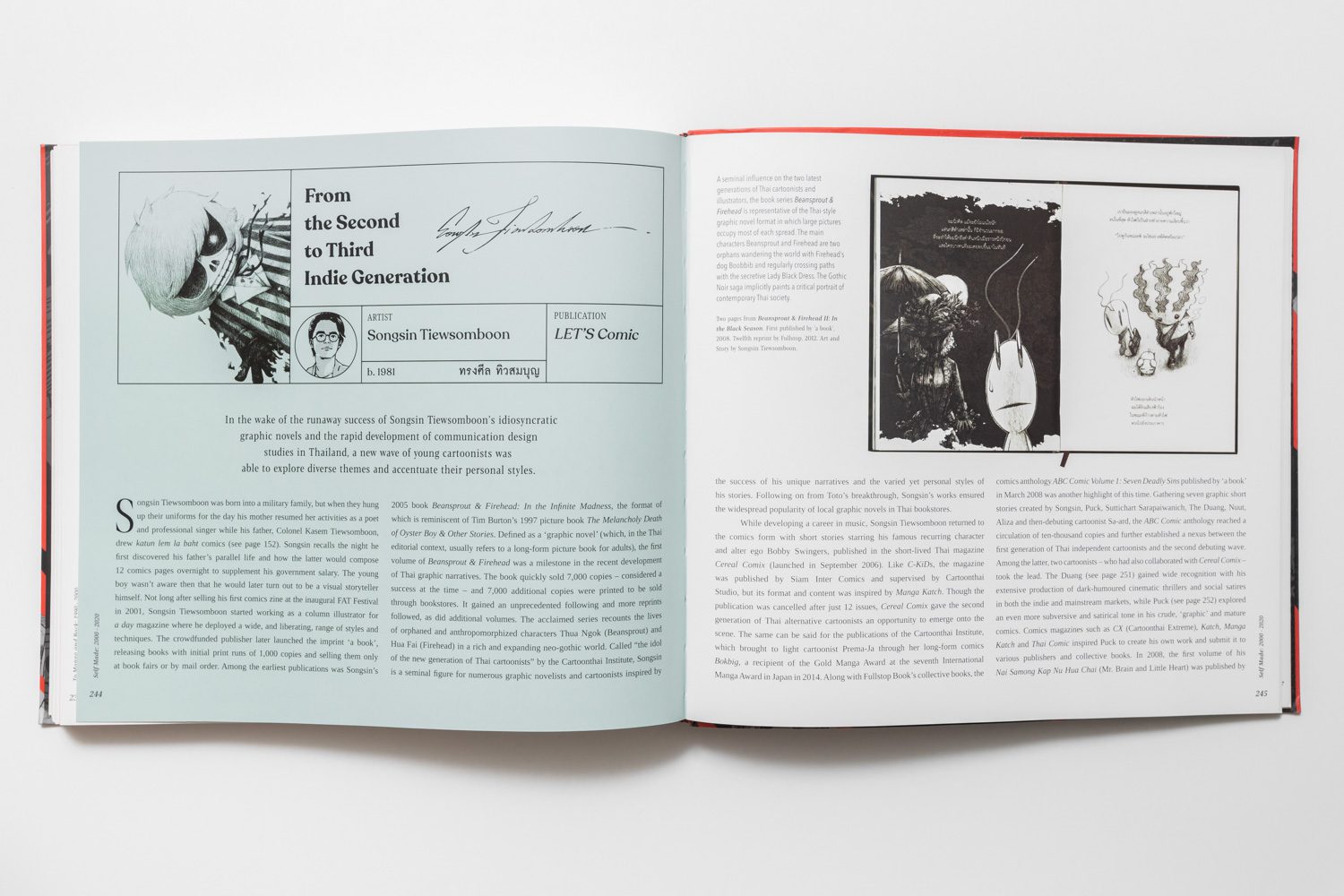

From 1997 onward, the book puts its focus particularly on Thai independent comics and rarely mentions mainstream pieces. 2007 is the last year of the century that Nicholas writes about. There really isn’t that much rationale behind it except the fact that the period between 1997 and 2007 is the decade that Thailand saw the heyday of alternative comics, which reached their peak and plateaued within that ten year span. The author’s conviction grants us readers with one fact about the actual scenario after 2007, which is the beginning of Thailand’s comic industry’s struggle that continues even until today. The contents he puts together from 1997 to 2020 forces one to accept the fact (which Nicholas himself also wrote in the introduction) that Thai people, be it the general pubic or the members of the academic sphere, have never appreciated comic art enough. And the reason isn’t too entirely complicated but merely because the majority of Thai people believe that comics are just a hobby for children and teenagers, or at times, a source of mass entertainment. The public has never acknowledged the significance of comics per se. Even the works published in newspapers during 1930s and 1960s, which had adults as the main target readers, were turned into a form of entertainment for children. Nicholas made an interesting discussion point that because middle class Thais who worked as office workers during the 1970s (2513-2523 B.E.) wanted to be respected within their social cycles, it forced them to discard what they regarded as too mainstream or typically local for their personal taste. They also pushed away Thai comic strips they once read in newspapers and labeled them as cheap entertainment for kids. In Nicholas’ perception and idea, Thai society did too little of a job in getting rid of the mindset that comics are for children, simply because the majority of the society was kept from acknowledging the diversity and popularity of Thai comics prior to 1997, the period in which Thai comics were connecting cultures, people’s lifestyles or even political ideologies and expressions.

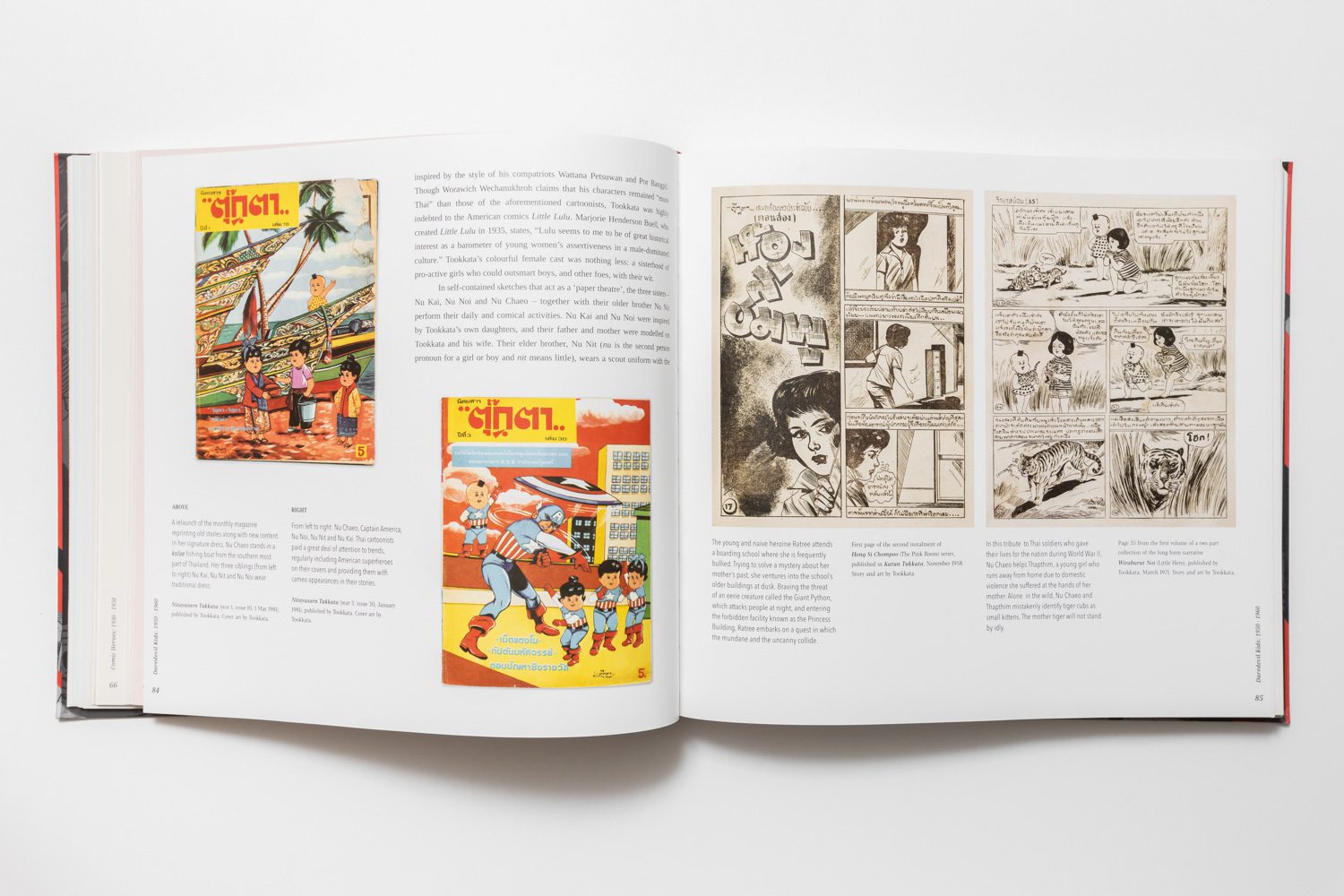

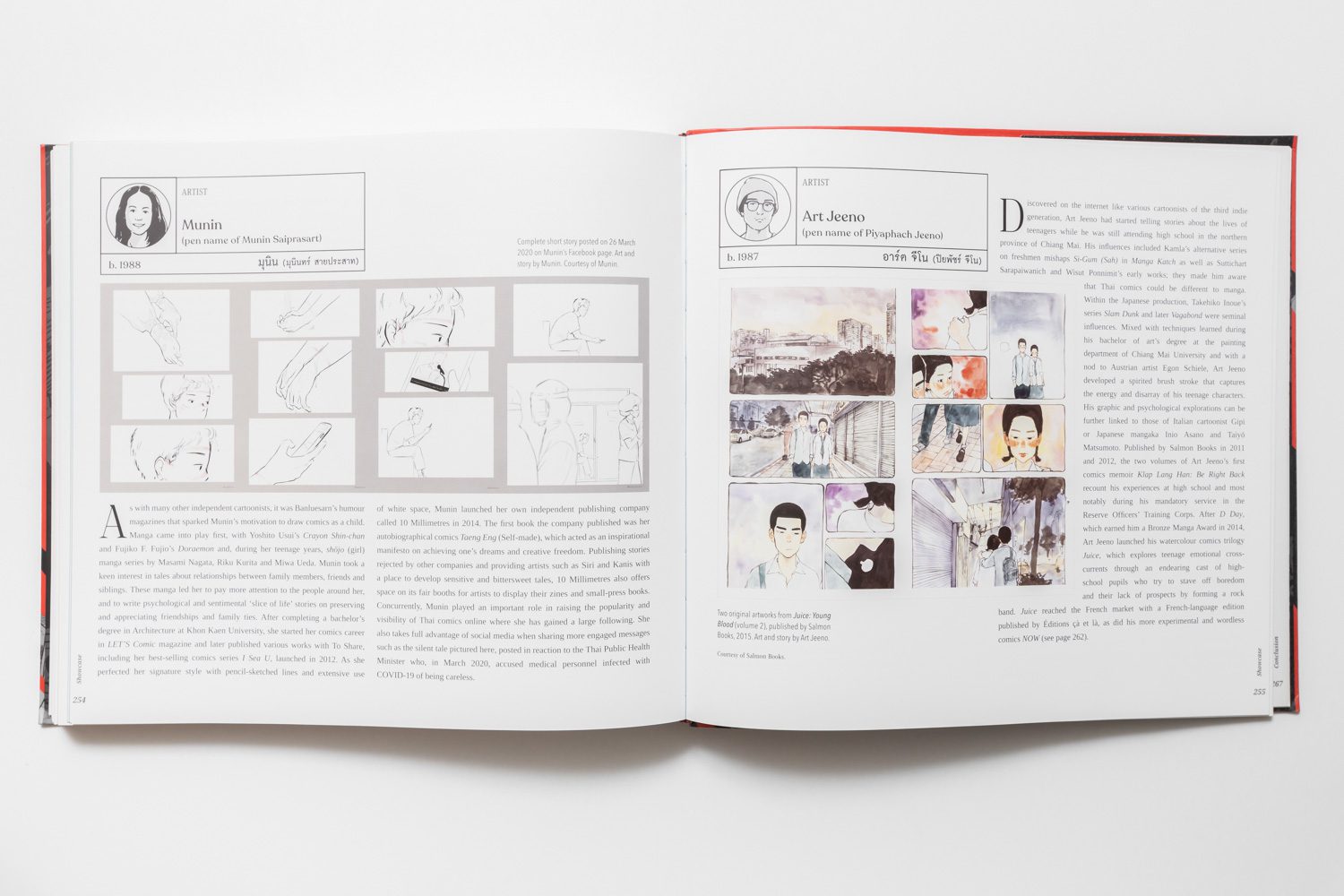

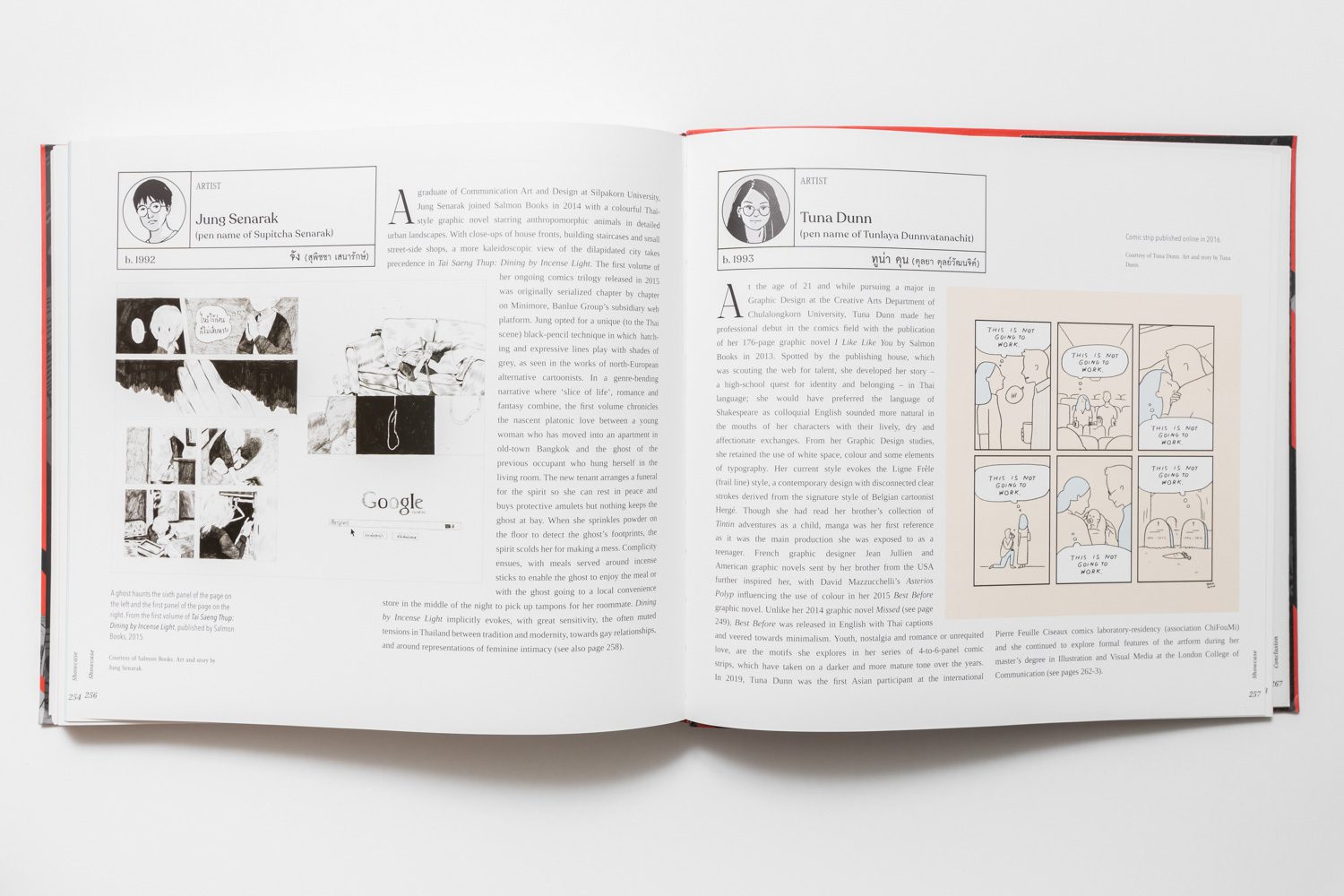

This book seeks for a balanced solution between; the author, editors, designers, information, contents, either scanned and regenerated, and newly created illustrations, the spaces and numbers of pages, the Thai and English format (which are designed to as similar to each other as possible), all a collective attempt to create an easier and enjoyable reading experience. Peerapat Kittisuwat and P. Library Design Studio came up with a solution, which is barely noticeable while skimming at first, but as one uses the book more and goes through the references, the appreciation in the details of the layout and how the book is designed and experienced in general will definitely grow over time.

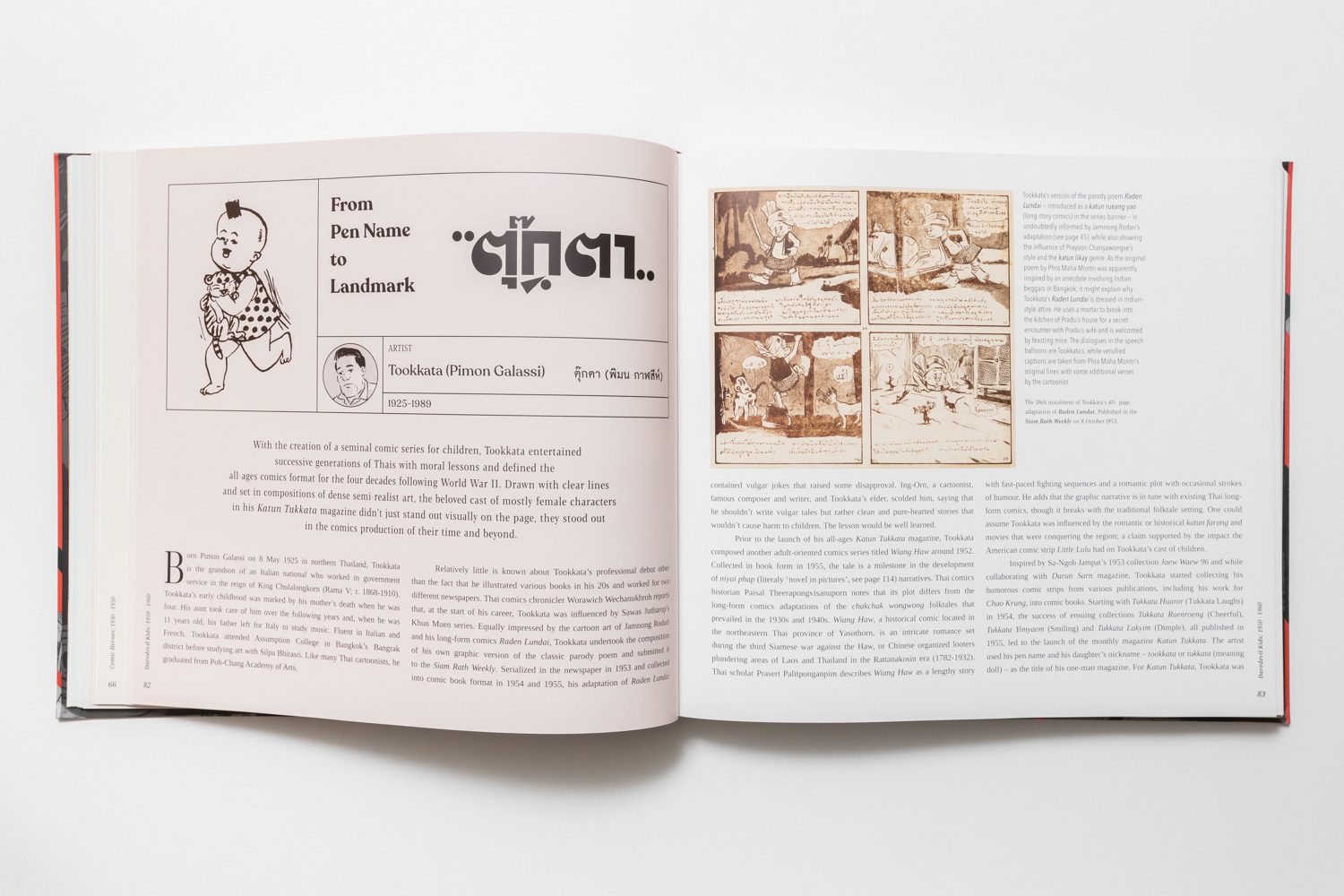

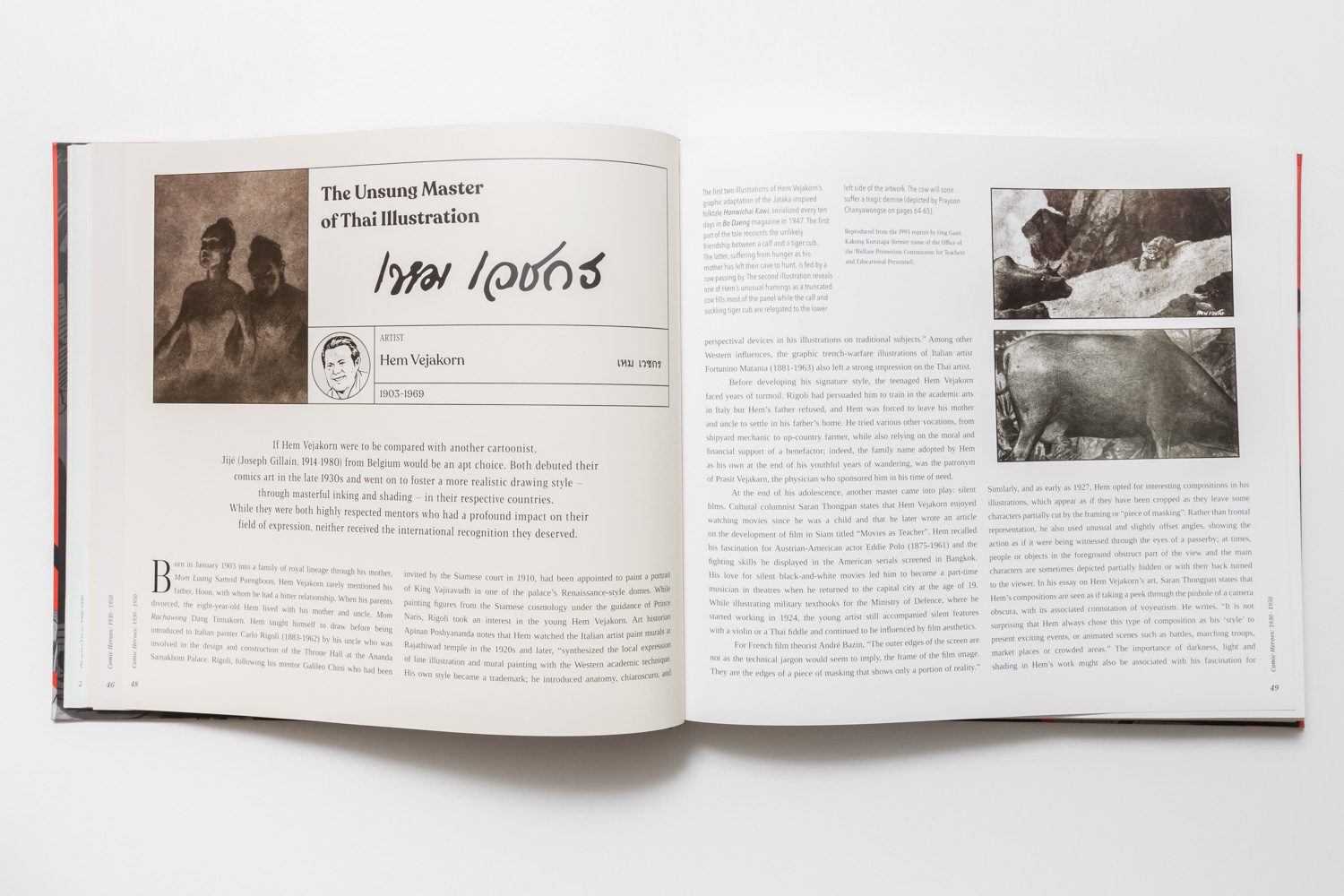

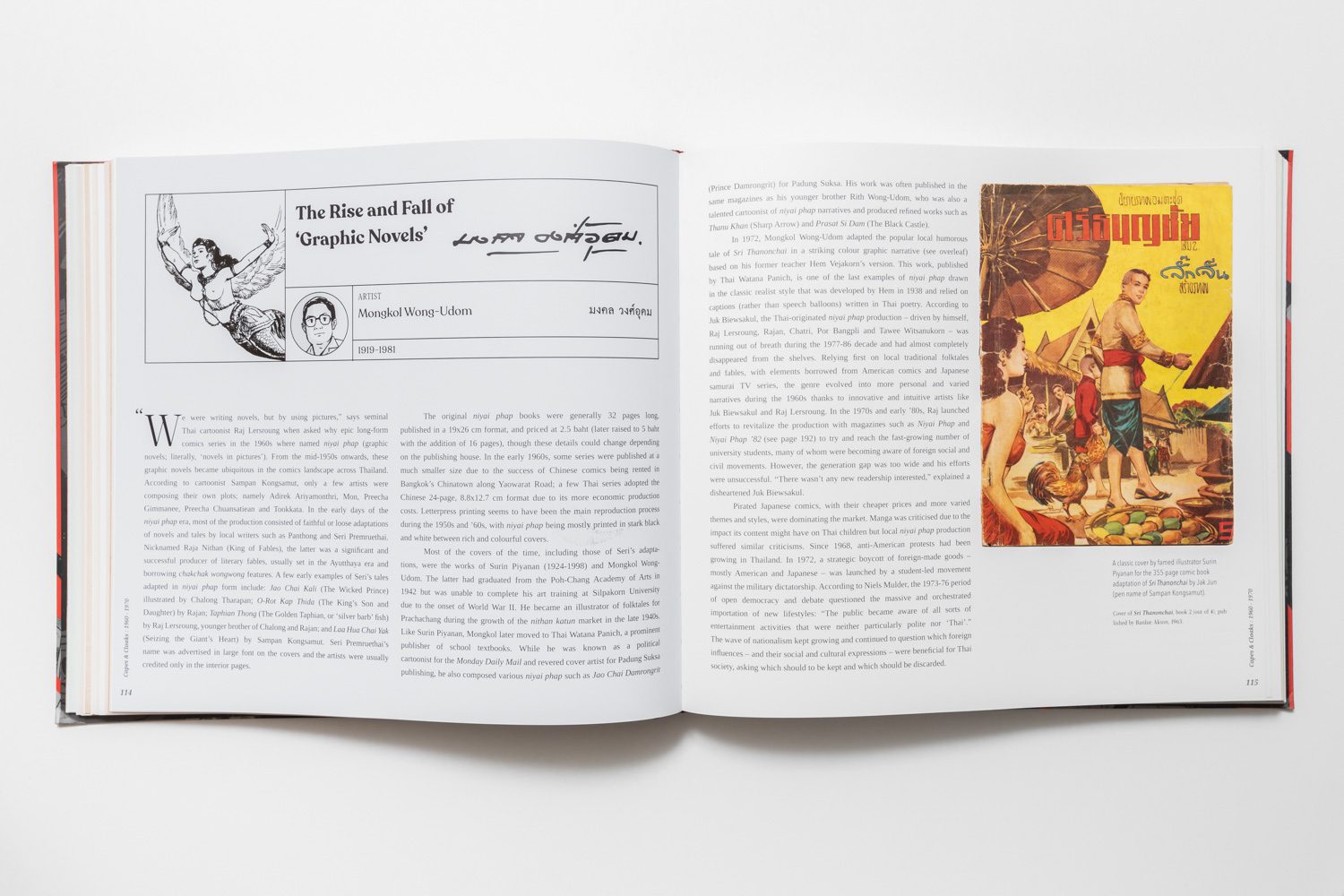

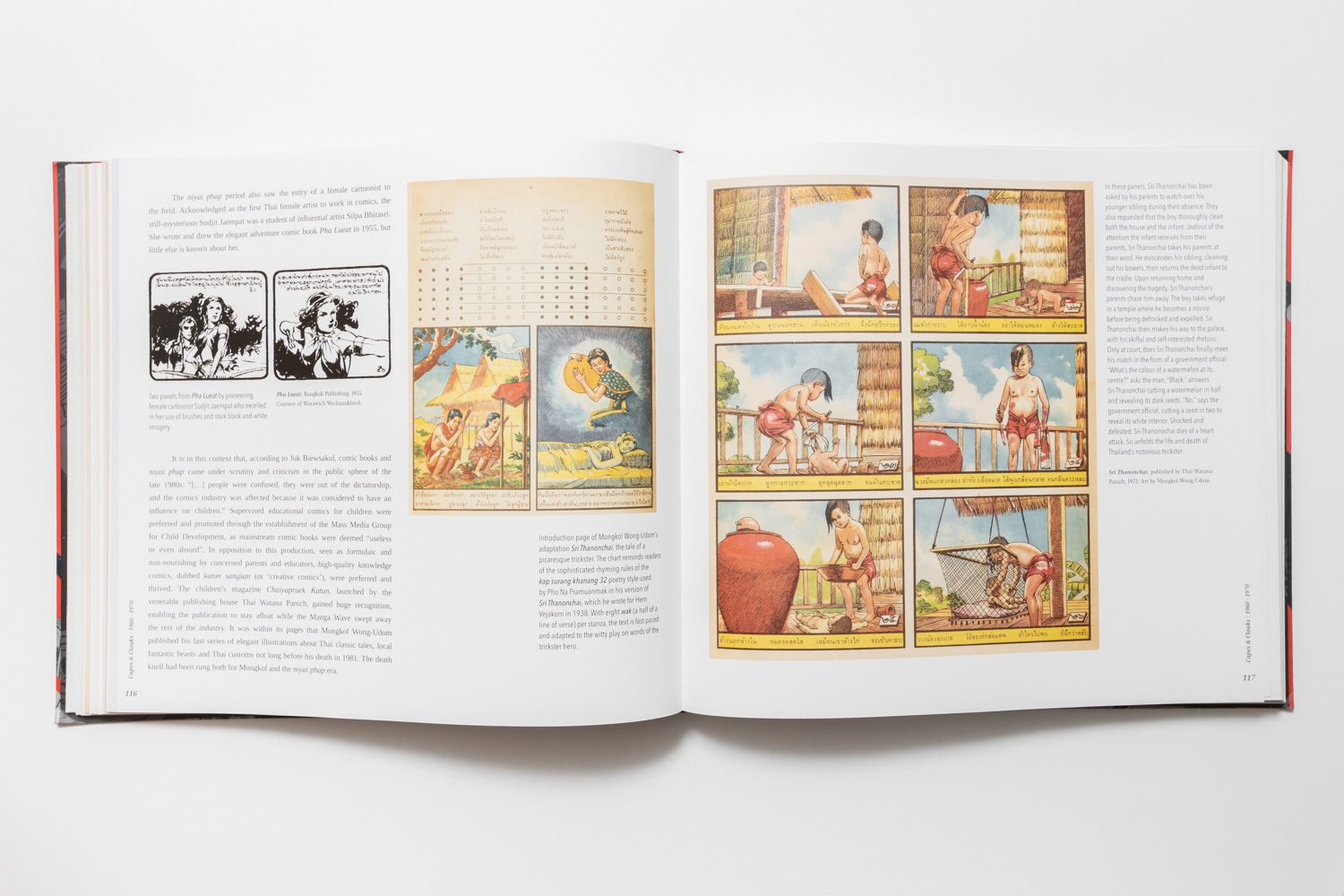

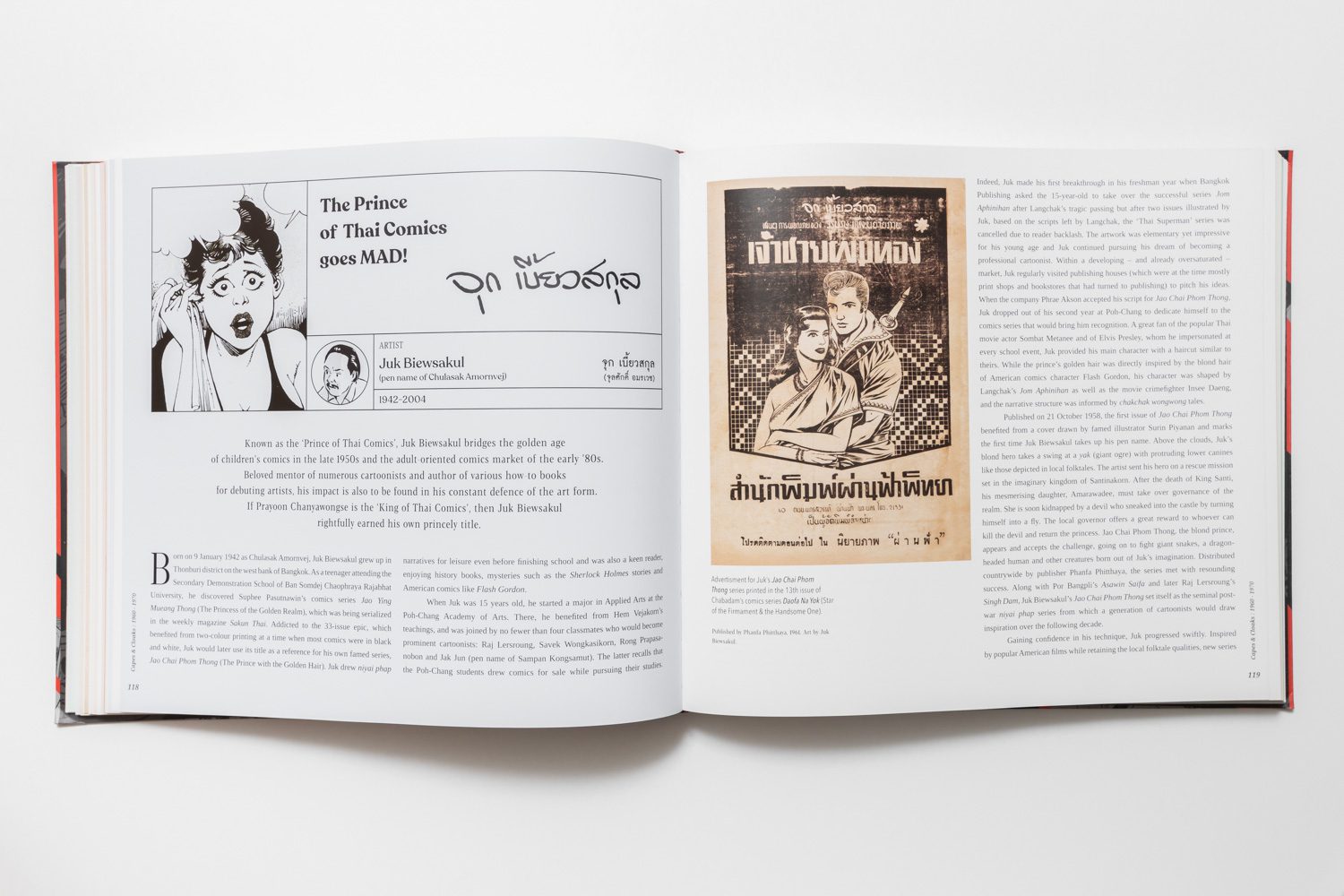

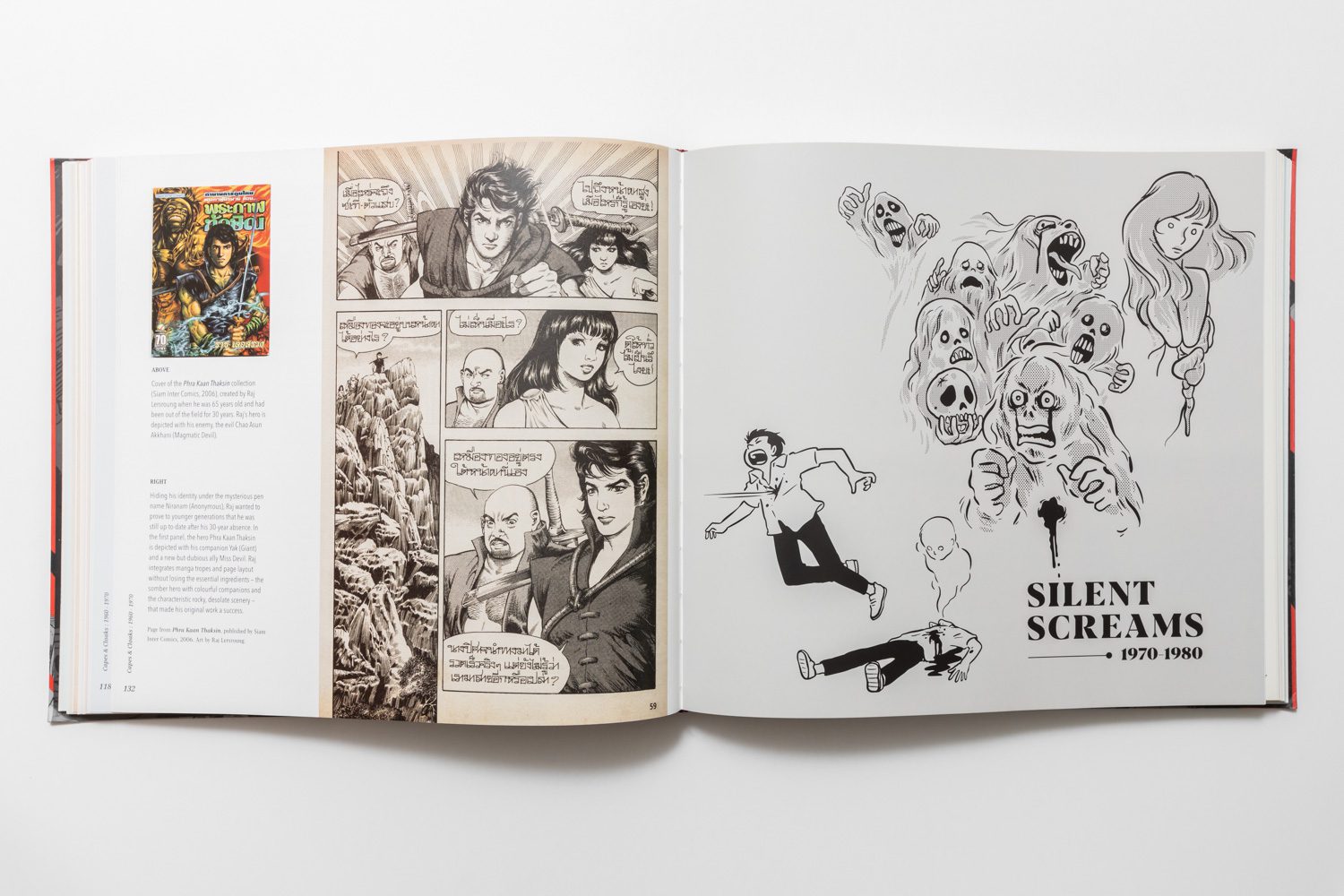

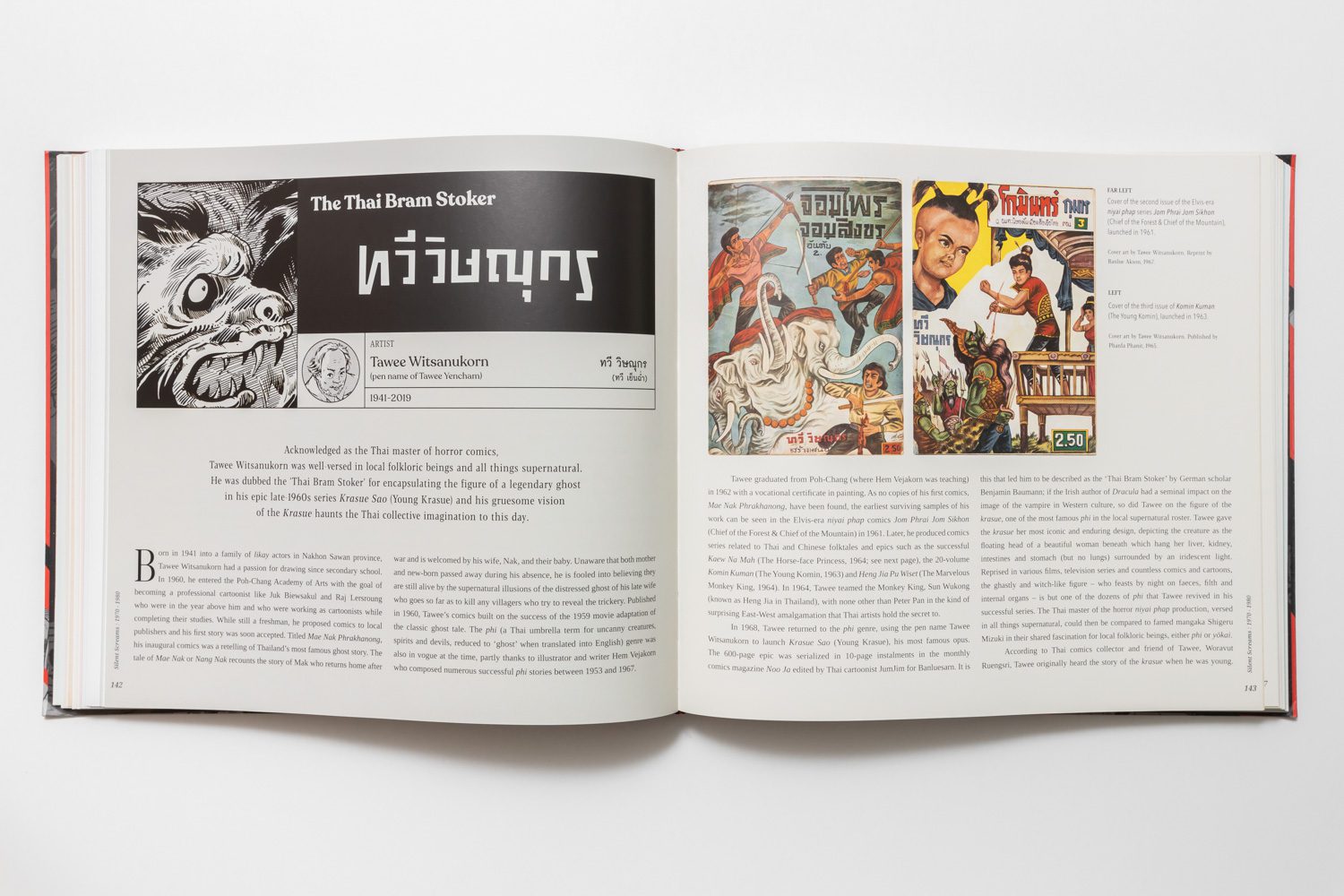

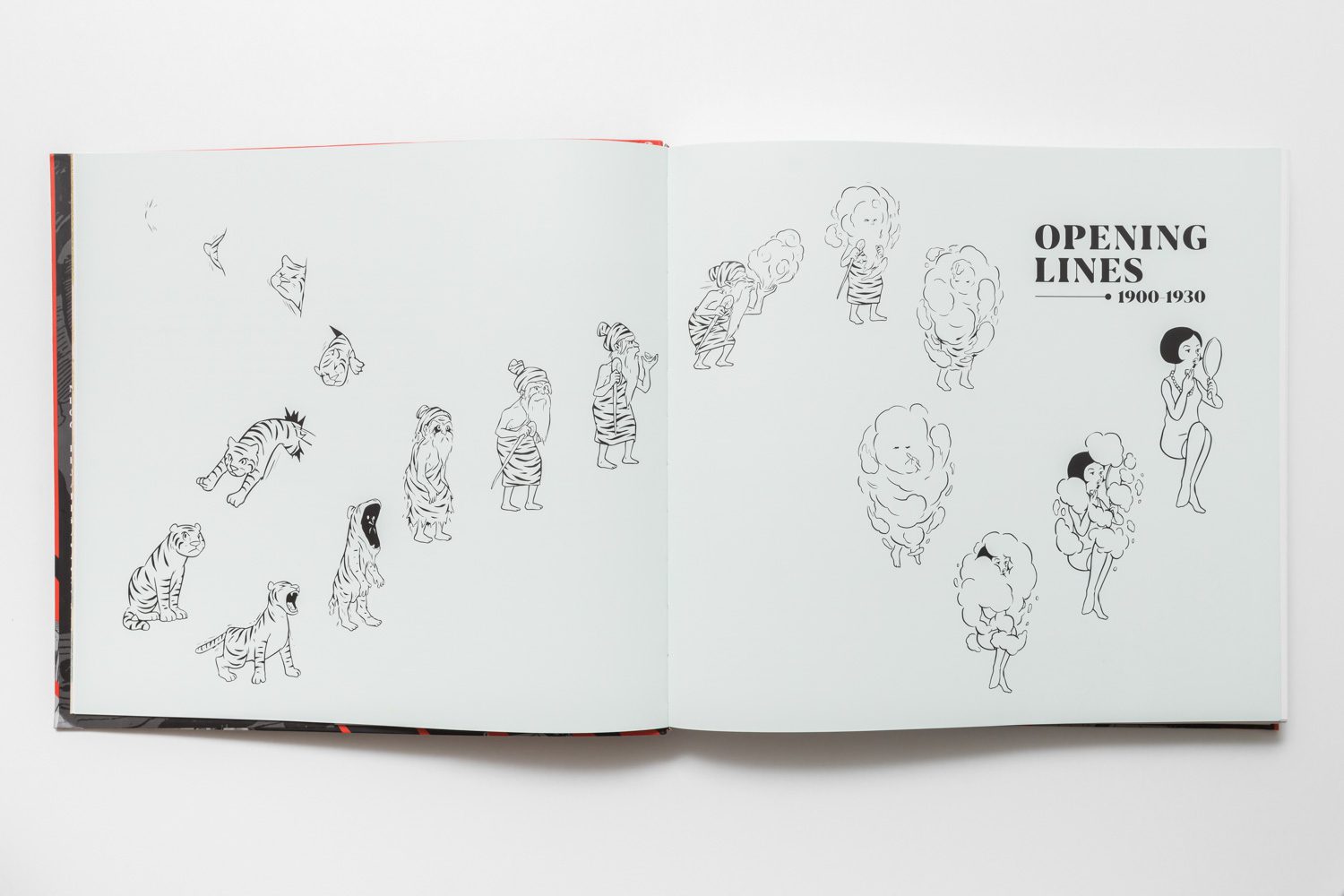

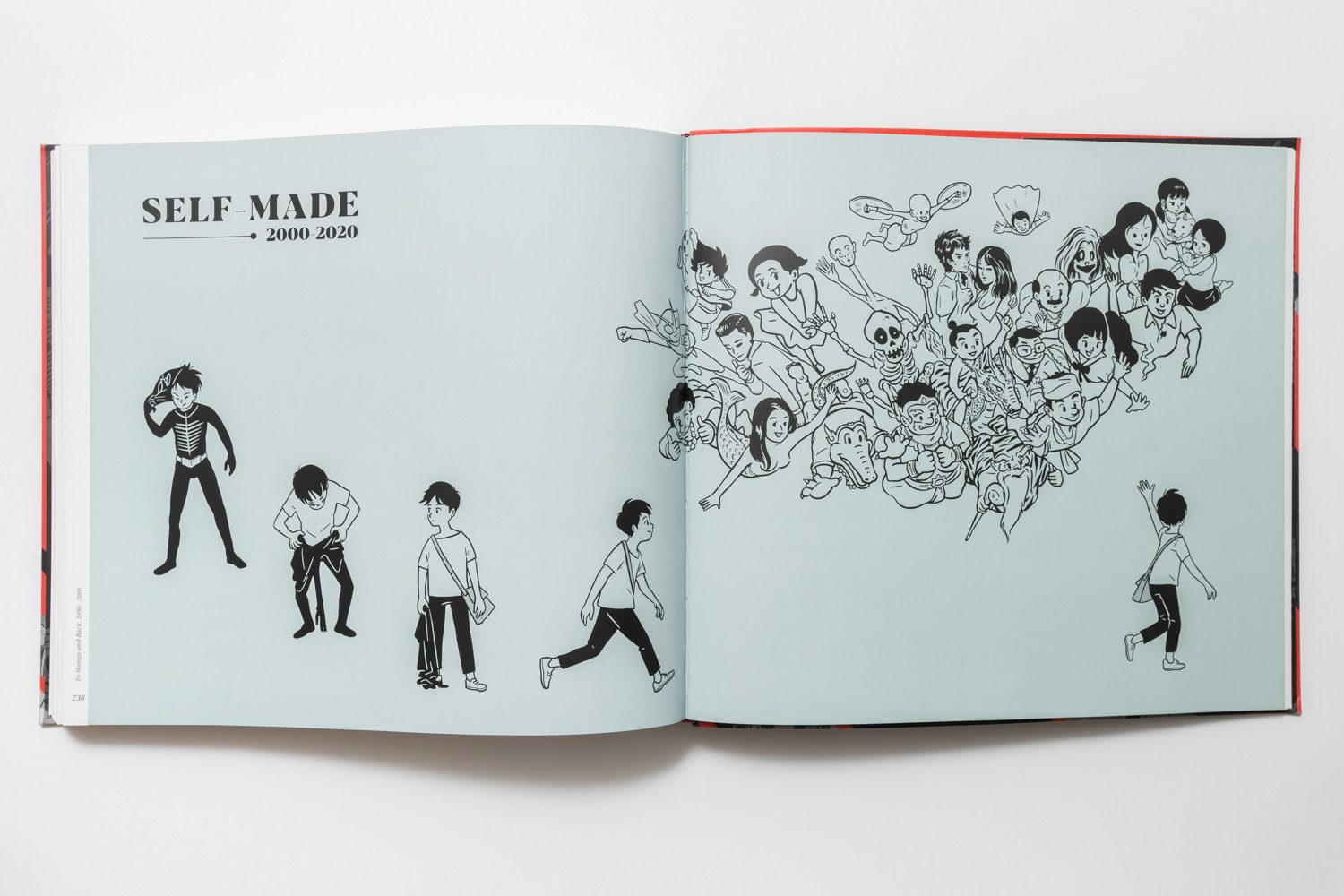

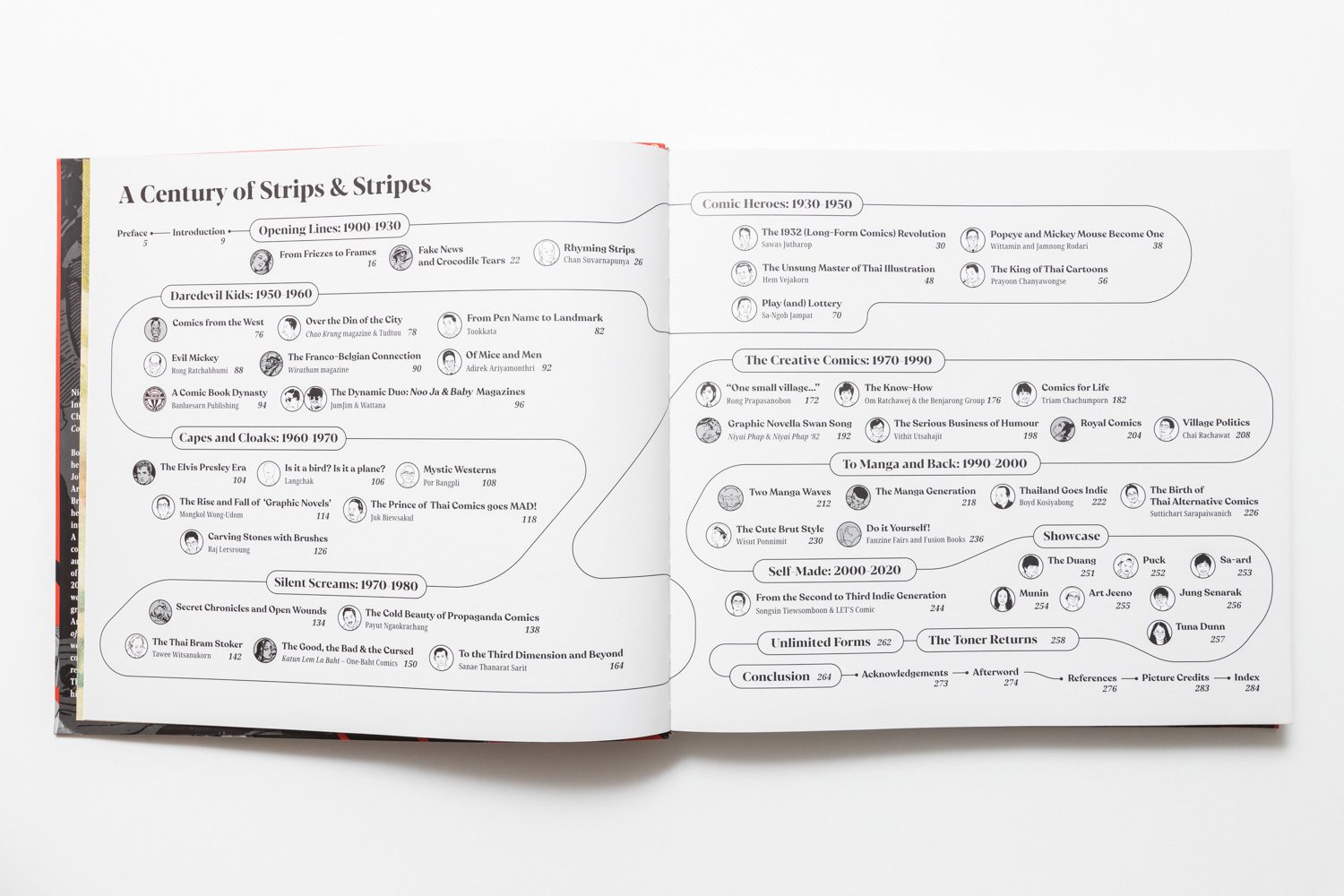

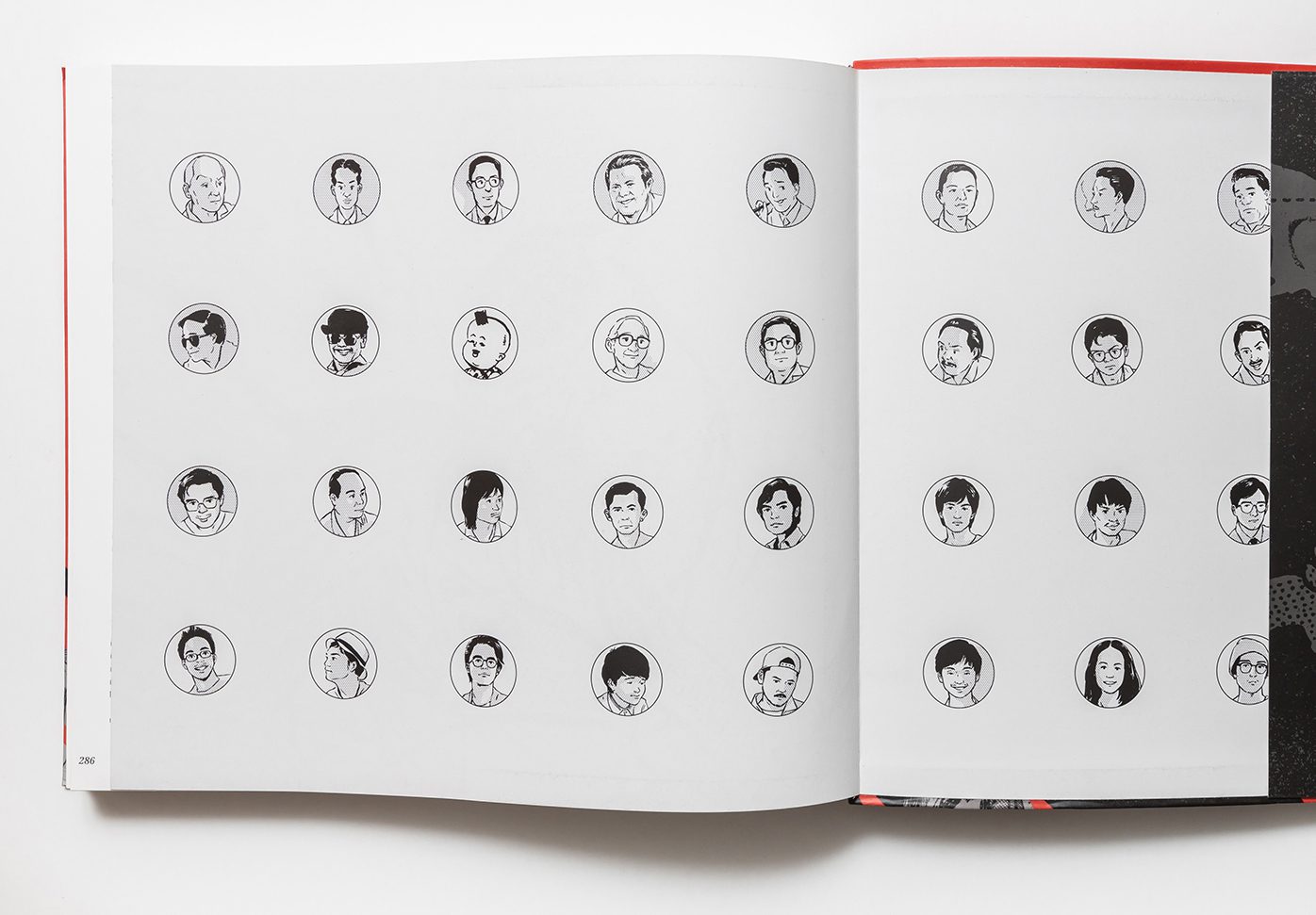

The details can be found in the form of the pages displaying the one hundred year timeline that also functions as the book’s table of contents, or the transformation from one character to another, which despite being executed as a simple animation, undoubtedly required a considerable period of time and determined decision making as to which character would be used in the opening page to introduce each era. Then there’s the system designed for each work’ title and front page to create a clear and memorable impression of the leading character of each comic that readers can easily pick up on, including the presentation of the artists’ signature, pseudonyms, real names, dates of birth and death dates. Also including the use of recreated portraits instead of photographs for many were too old or of too low quality to be published.

As mentioned earlier that this book can complicate Thai readers’ decision on whether to buy the English or Thai version, which isn’t because of the feel that comes with the original English version or the Thai version, which would obviously be easier and more comfortable to read. Although the translation is understandably never going to grab all the linguistic nuisances of the original, and it isn’t about the uncertainty when coming across the English spelling of Thai names or specific Thai words, which is almost impossible to grasp and express the actual pronunciation unless there’s a Thai version to compare. The larger and serious issue than all of these is the captions of the illustrations and images of the two versions, which are way too different to ignore. For instance, in the English version, there are extra explanations provided in the parts that talk about Thai literature, which is an area that most Thai people are already familiar with. Nicholas did mention that he spent a majority of his time working out this particular section of the book, and on providing the cultural and historical backgrounds for the non-Thai readers. There are also the parts that provide additional information about the foreign comic artists who inspired many Thai comic masters, which are done for the sake of Thai readers who may be unfamiliar with their names and works. My guess is that with the limited page numbers, to include 1:1 content must have been impossible unless the letters were reduced into a size that would be too small to read.

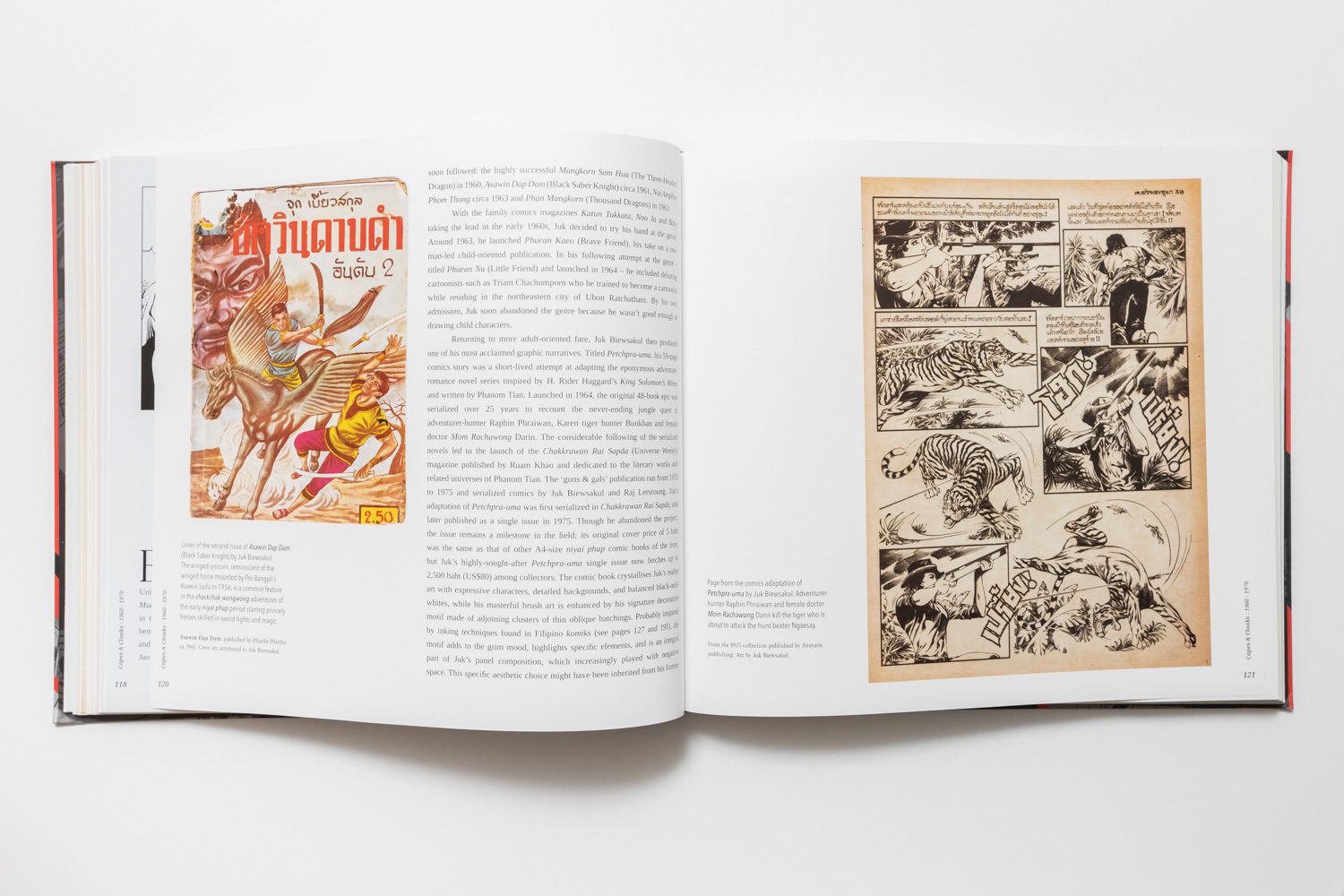

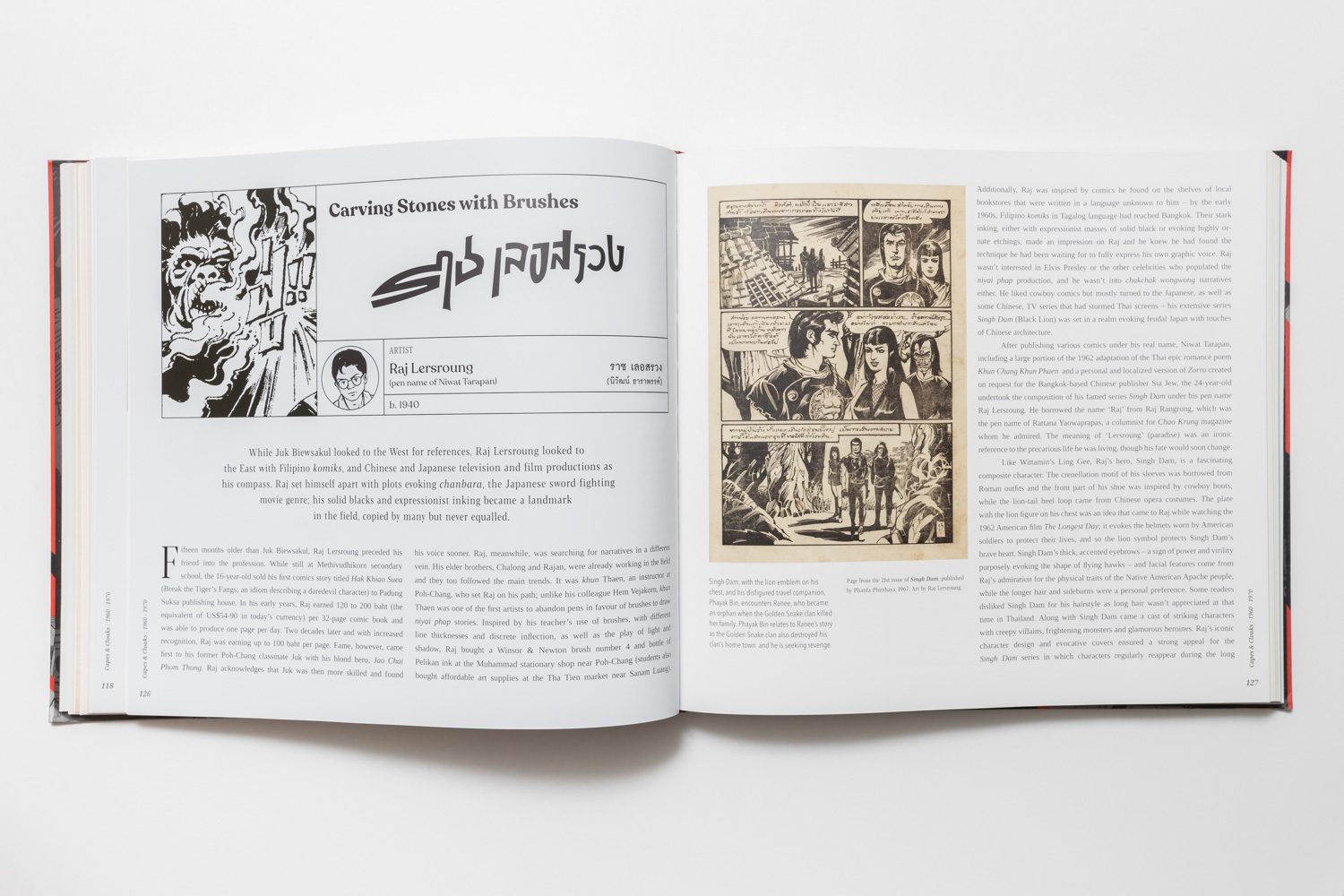

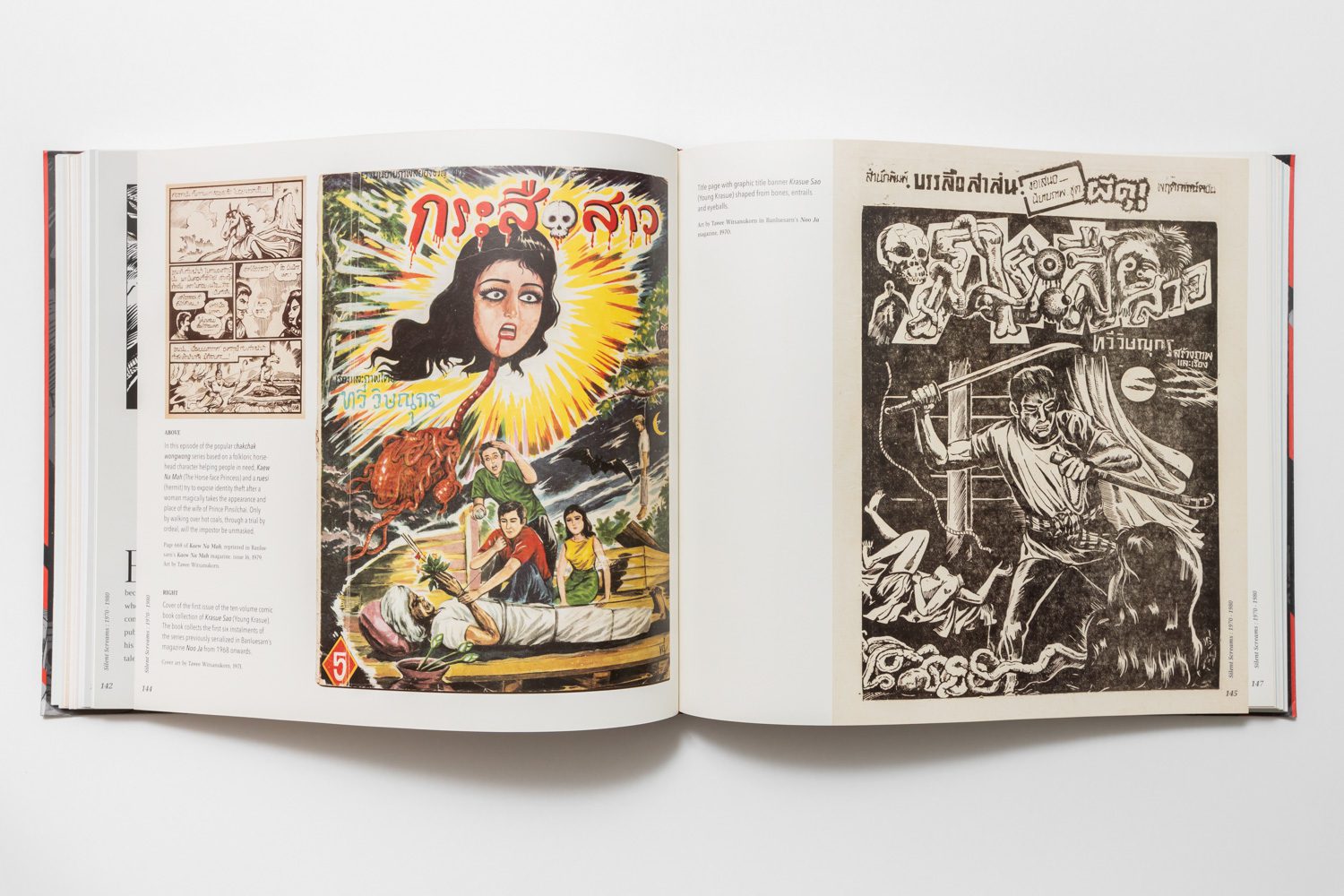

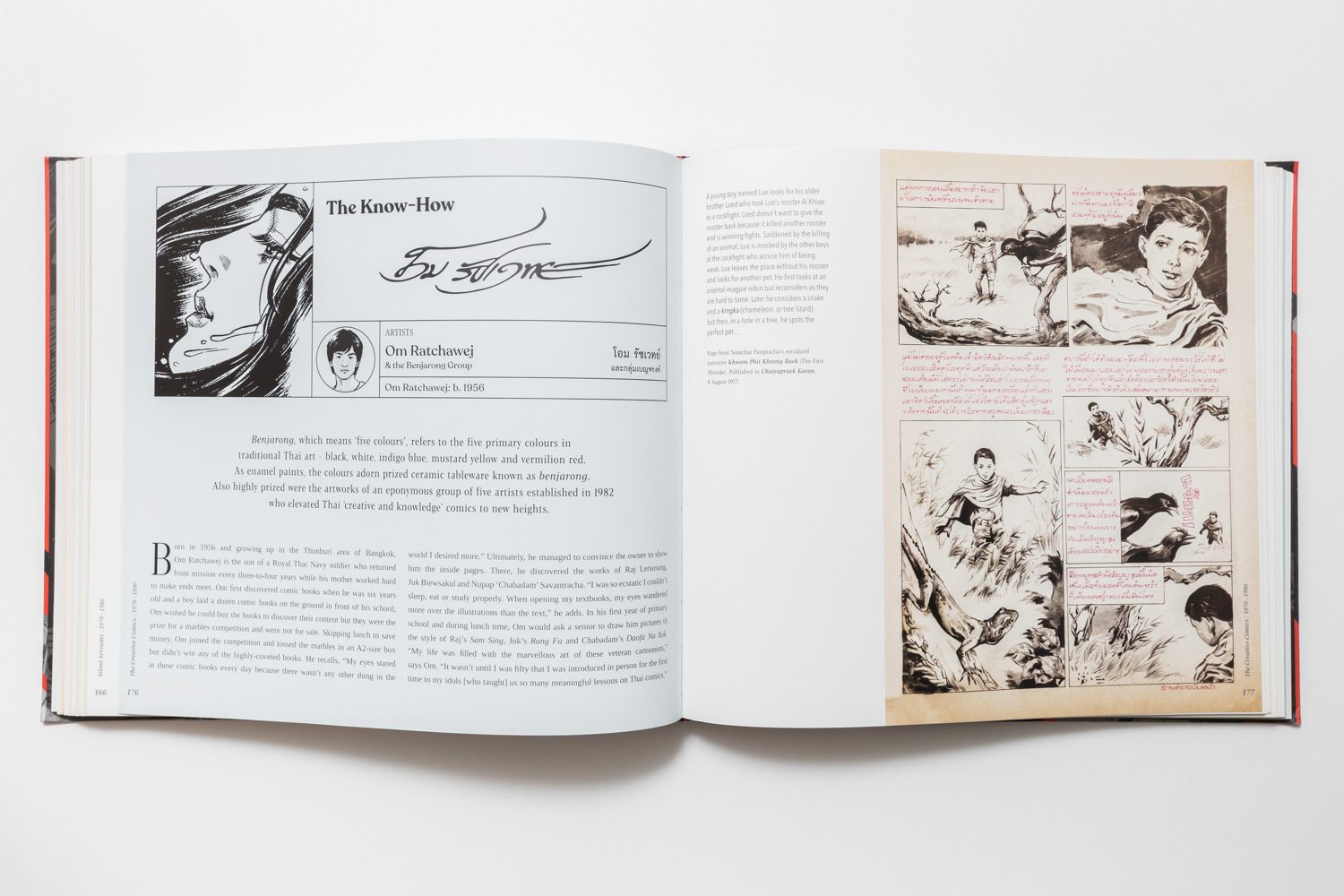

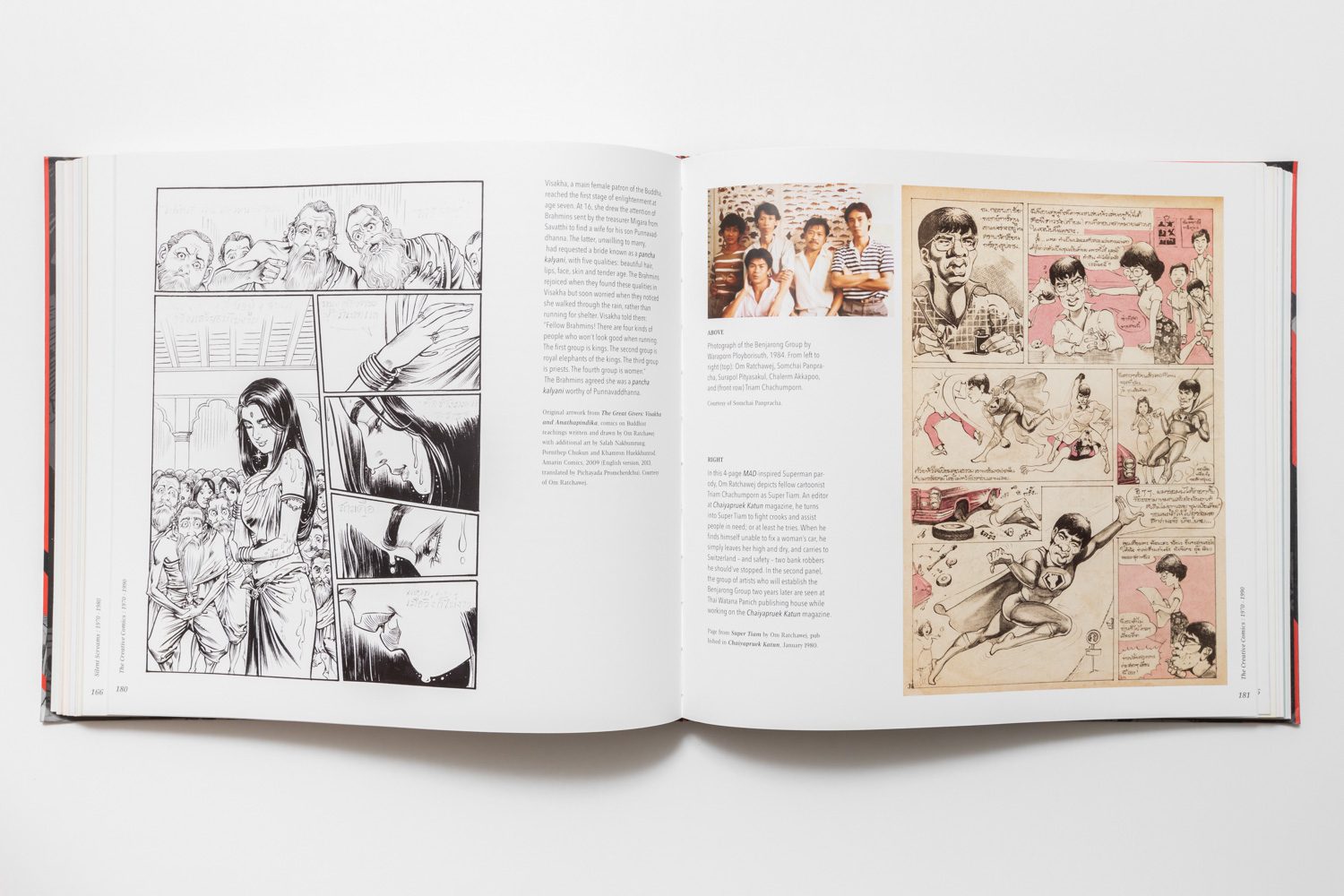

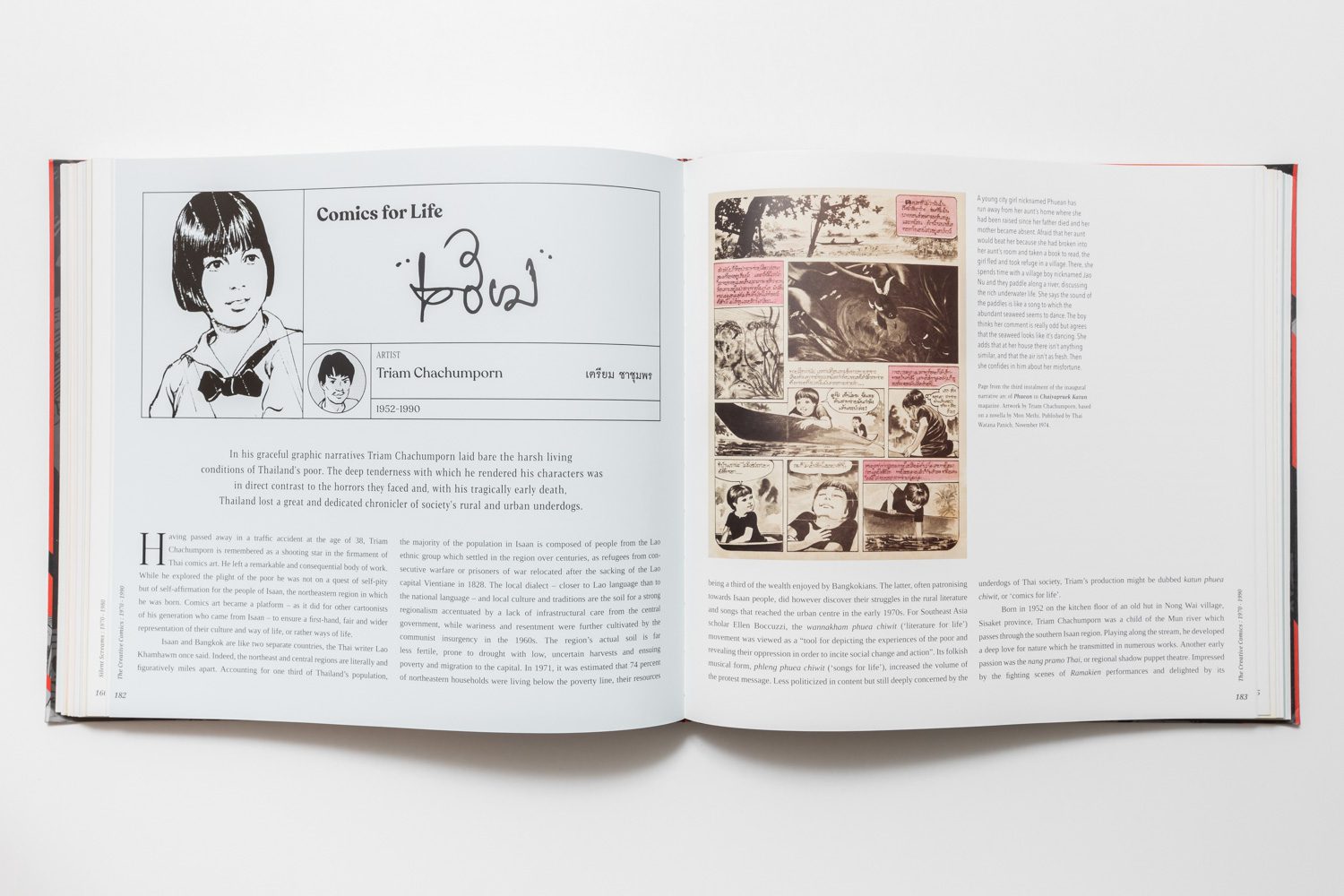

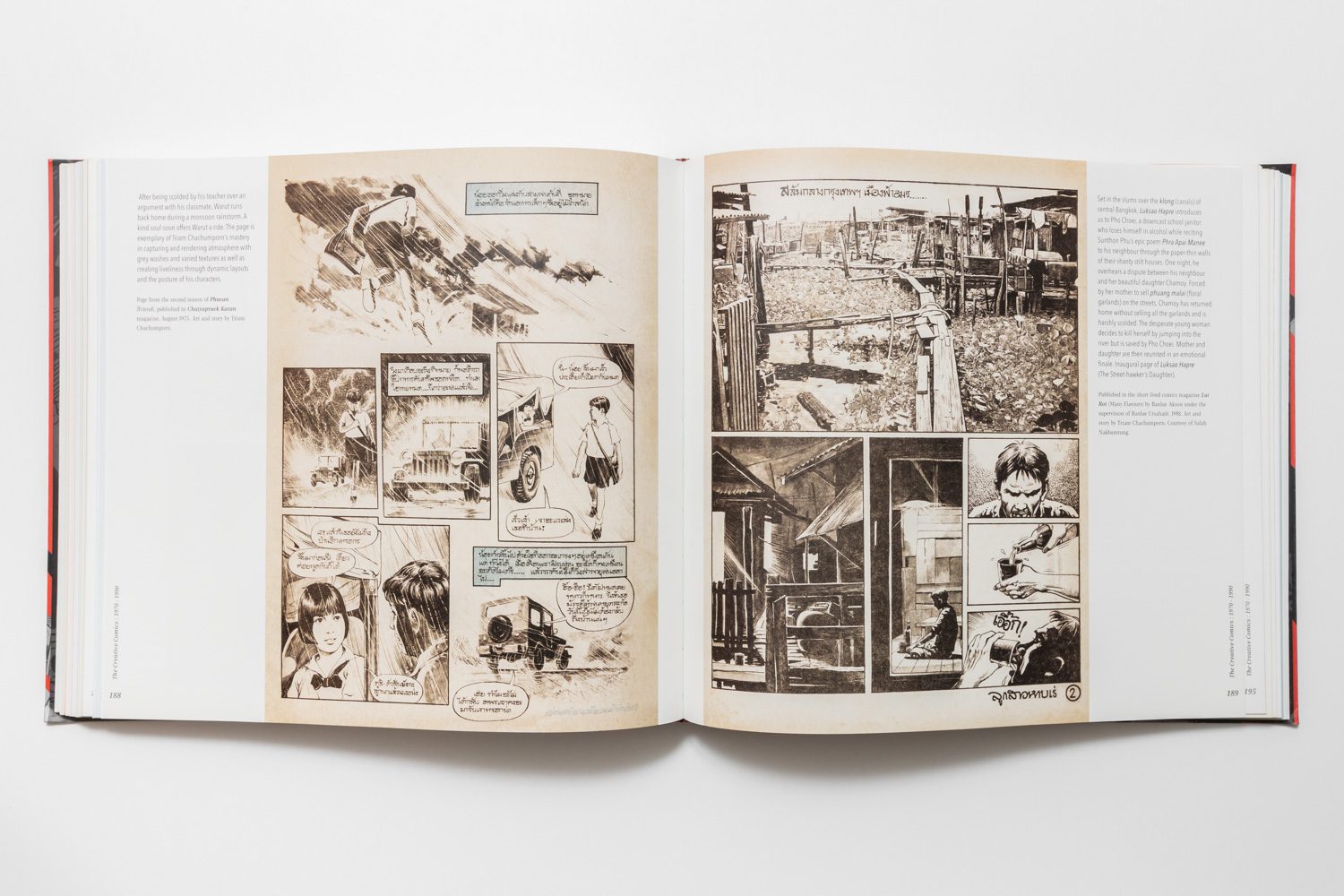

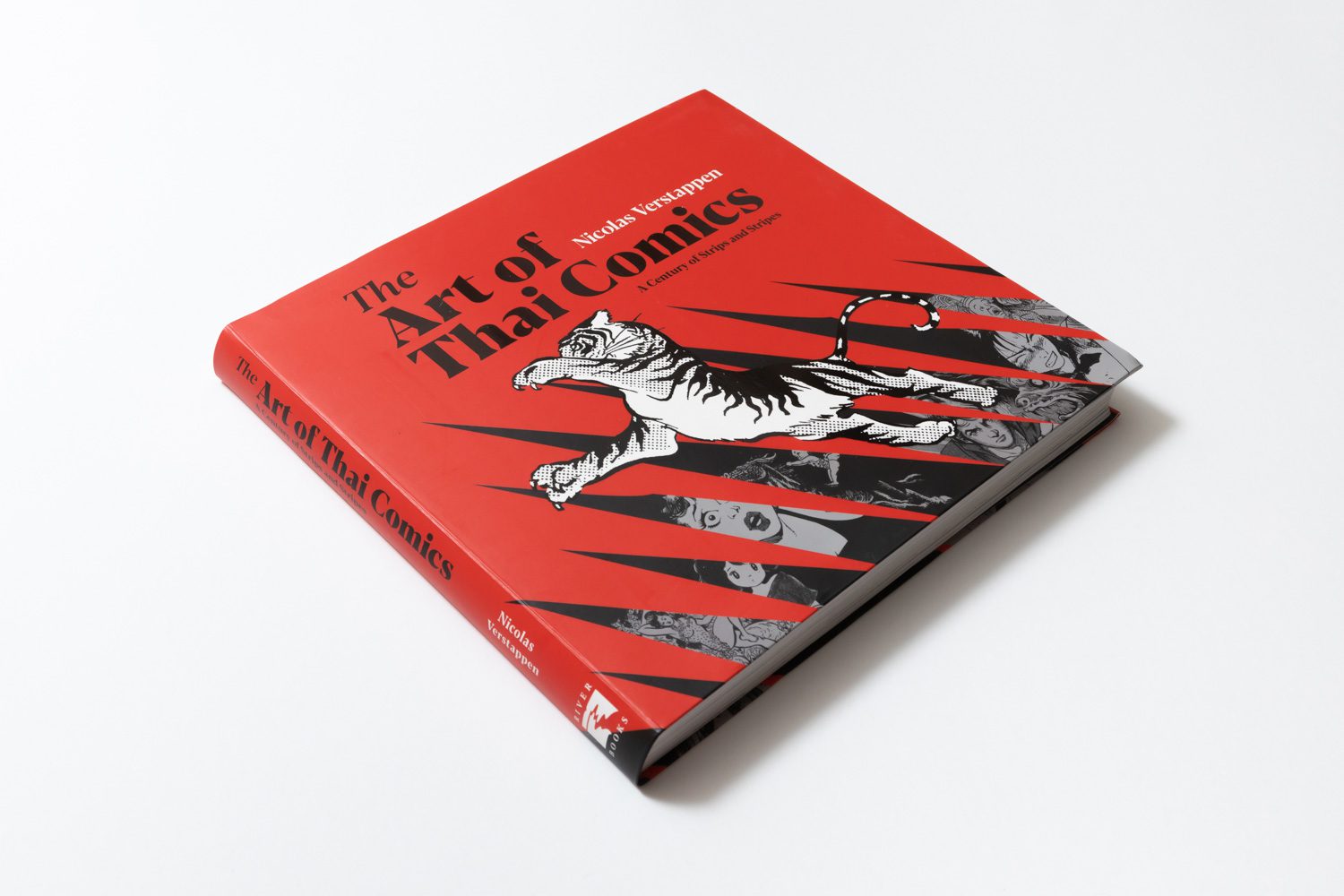

Having said that, just the scanned and restored images of the original comics alone, (Peerapat and his team are fully credited for their amazing work in handling the original documents. Despite facing various conditions, from papers that turned yellow, while some were damaged with holes or eaten by worms) make the book so impressive in and of itself. What the book achieves with its contents, as well as the regeneration and publishing quality that allows us readers to see the works of Hem Vejakorn, Witt Suthasatien, Jamnong Rodari, Prayoon Chanyawongse, Mongkol Wong-Udom, Juk Biewsakul, Raj Lersroung, Tawee Witsanukorn, Om Ratchawej and Triam Chachumporn, in such incredible condition is astonishing. In addition, Prayoon Chanyawongse‘s illustration of a tiger jumping over a cow on the red cover (although the cow is made absent because the work is actually an adaptation of a Likay (a folk theater) story called Honwichai Kawee, which was published in the Pim Thai newspaper around 1950) has allowed the book to be listed as one of the 100 books that Thai people (and I mean people in general not just children) should read in the 21st Century.