THE NEW SEWING BUILDING OF LONG GOY, A CLOTHING BRAND FROM CHIANG MAI, DESIGNED BY SHER MAKER, CONVEYS A SENSE OF PLACE, WHICH IS THE SHARED ESSENCE OF BOTH BRAND AND THE ARCHITECT

TEXT: MONTHON PAOAROON

PHOTO: RUNGKIT CHAROENWAT EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

We arrived in Chiang Mai’s Sanpatong district in the afternoon to meet with Supakorn Sunkanaporn, the owner of the local clothing brand LONG GOY, specifically to visit its newly completed studio/workshop. Its striking dark blue wall drew our attention as we passed the entrance to enter the building, which was designed by Sher Maker, a Chiang Mai-based studio.

Supakorn began by providing a brief history of his LONG GOY brand. It arose from his bachelor’s degree thesis and desire to modernize the province’s local cultures, as well as his personal connection to and experience with clothing as a result of his family’s business, which was a sewing factory producing traditional northern apparel. And by factory, he meant the area beneath his mother’s stilt house’s elevated floor. In his thesis, he applied the washed jeans technique in street fashion to Mo Hom, a locally made textile, by designing a new pattern with a laser-cut stencil incorporated to render more refined details. Supakorn recalled his lack of fashion knowledge, and the stumbling through trials and errors that led him to name the brand LONG GOY, which translates to ‘let’s try it out’ in the northern Thai dialect.

Photo: Monthon Paoaroon (left)

Supakorn had no orders when COVID-19 went into effect in 2019, since the majority of his clients were foreigners. However, the disruption provided Supakorn with an opportunity to reflect. He decided to continue his education at Bunka Fashion School. Supakorn chose to design an office uniform that would tell the story of Lanna from a new perspective for his thesis. When viewed from different angles, the skirt, which was made using the pleated technique, reveals two different colors. The technique that was the highlight of his thesis collection later became the design concept for this new building.

Photo courtesy of LONG GOY

Photo: Monthon Paoaroon

Supakorn’s inspiration for relocating the sewing operation into a separate building came from the dim and poorly ventilated space beneath the stilt house’s elevated floor. Patcharada Inplang, Sher Maker’s architect and his senior at King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Lad Krabang, was contacted to work on the design. Patcharada was dressed in a blue overshirt that she wore so frequently that it had practically become her uniform on the day of their meeting. And, as you might expect, it was a piece from LONG GOY’s collection, a brand she has long been a fan of.

The new sewing building was built near his family’s house, replacing the old rice barn, which had been relocated. The architect attempted to integrate the new structure with the existing family home, resulting in a design that is similar in size and proportion to the existing residential structure. The sewing workshop, which occupies 80% of the L-shaped building’s functional space, houses approximately 20 sewing machines that produce both LONG GOY products and traditional clothes of Supakorn’s mother’s tailoring service. The remaining 20% is saved for Supakorn’s stencil workshop, office space, gallery space, and an area where he works on various other experiments.

The sewing section is designed to be a lofty and open space, allowing for plenty of natural light and optimizing natural ventilation. Due to the dust and debris from scrap fabrics, no air conditioning system is installed in this space. Supakorn’s office is located at the back of the protruding end of the L-shaped building. The stencil workshop is located on the first floor, where he creates patterns for LONG GOY’s clothing items. The area is designed to be open and well-ventilated due to the odor caused by the use of potassium permanganate in the colorization process. The office space is on the second floor, and workshops are held in the outside garden at the back of the building. Supakorn and his mother collaborated with the landscape architecture team to gradually develop the garden’s design, which reveals a series of lines created by the spans between the tree lines, in accordance with the owners’ desire to preserve all of the trees that had grown on the property. An opening is added to the gallery space to grant visual access to the garden, allowing visitors to a passageway leading to the back of the property that can be accessed without having to walk past the sewing workshop located toward the front.

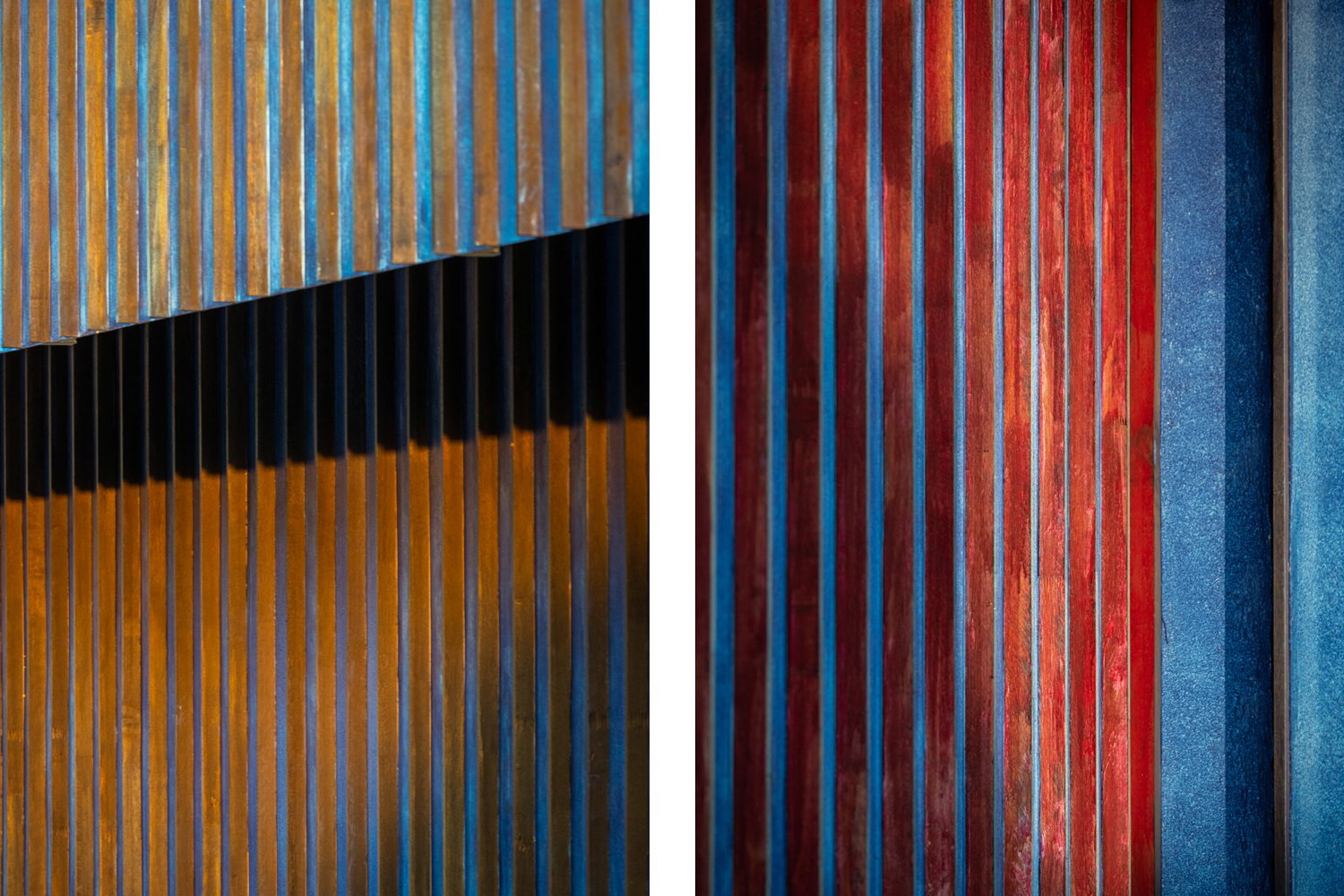

Patcharada explained that the distinctive dark blue wall that caught our eye earlier is designed to extend as a solid façade due to the exposure to the intense sunrays coming from the south. In addition, the architect designed the building with a void between the first and second floors to enhance airflow and ventilation in the sewing hall. Patchara joked that the process was a lot crazier than they thought during the design development stage, when Sher Maker tried studying different possible designs of the wall. Because there is always a lot of waste material from sewing process, they toyed with the idea of using fabric scraps as the wall’s finishing material. Supakorn not only never interfered with any of the ideas, but also encouraged the design team’s creativity. They eventually came to the final conclusion—a common ground that would allow the building to be built as a tectonic structure by local builders and artisans at a reasonable cost, thus the use of a steel structure and smartboard partitions.

Photo: Rungkit Charoenwat (left), Photo courtesy of Sher Maker (right)

Photo courtesy of Sher Maker

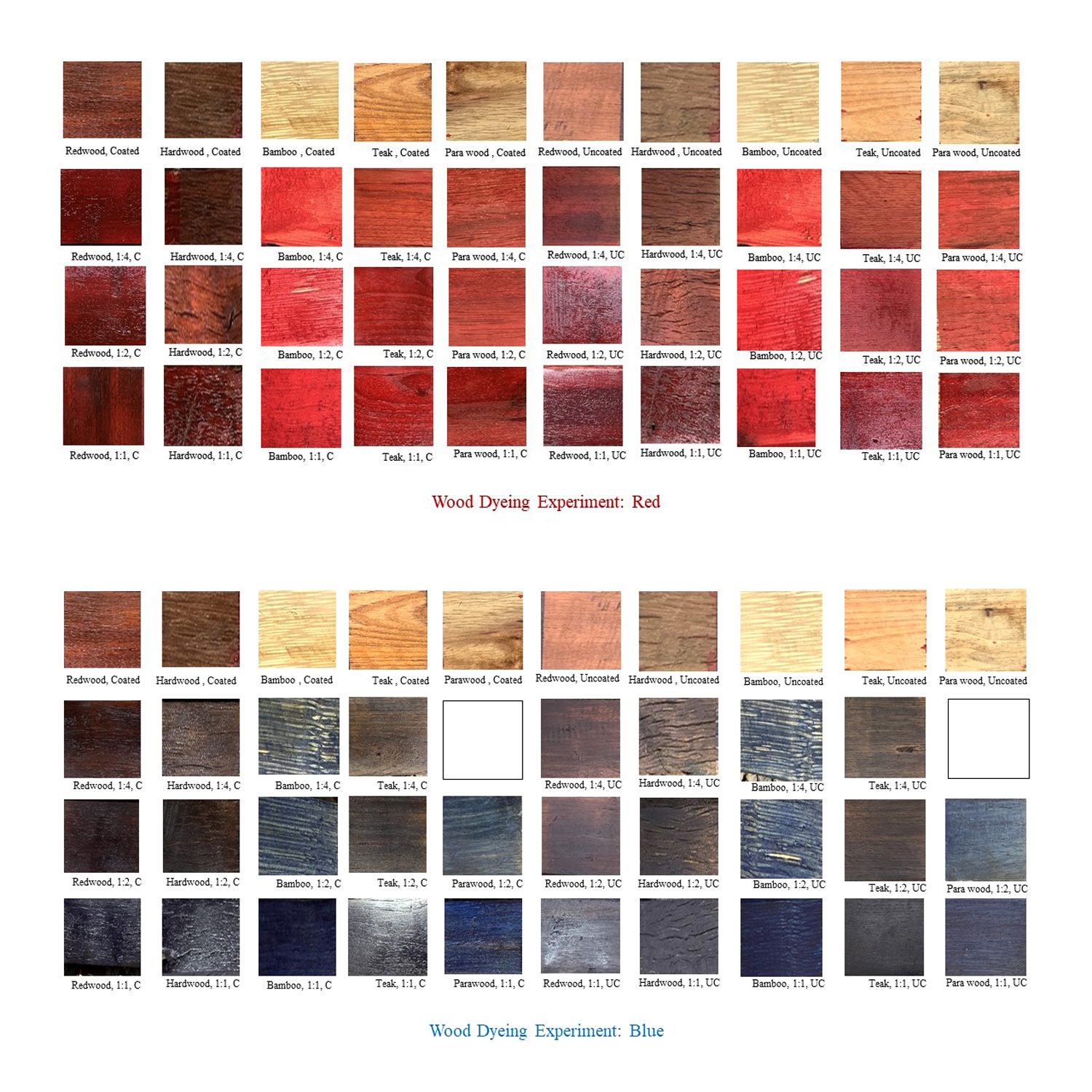

Sher Maker proposed using the pleat technique inspired by Supakorn’s thesis project to break down the wall’s monolithic mass. They tried on various colors, including ‘hom’ (the blue tone of Mo Hom textile). The design was refined until it was settled on the dark blue tone, which renders more graphic elements. The family’s old wood scripts were pressed and installed in a calculated sequence, with red painted on one side and dark blue painted on the other. When viewed from the outside, the building reveals itself in the dark blue color, and when viewed from the inside, it appears reddish-brown. Supakorn explained that he chose this combination of red and dark blue because he wanted the new structure to blend in with the color of the old wooden house when viewed from the inside out. During the construction process, the architect and builders discussed the watercolor-like finish with brush stroke traces and repetitive textural details that would match the red wooden trims. The requirement was difficult for the painters because they are used to painting walls with smooth textures, but the end result is satisfying nonetheless.

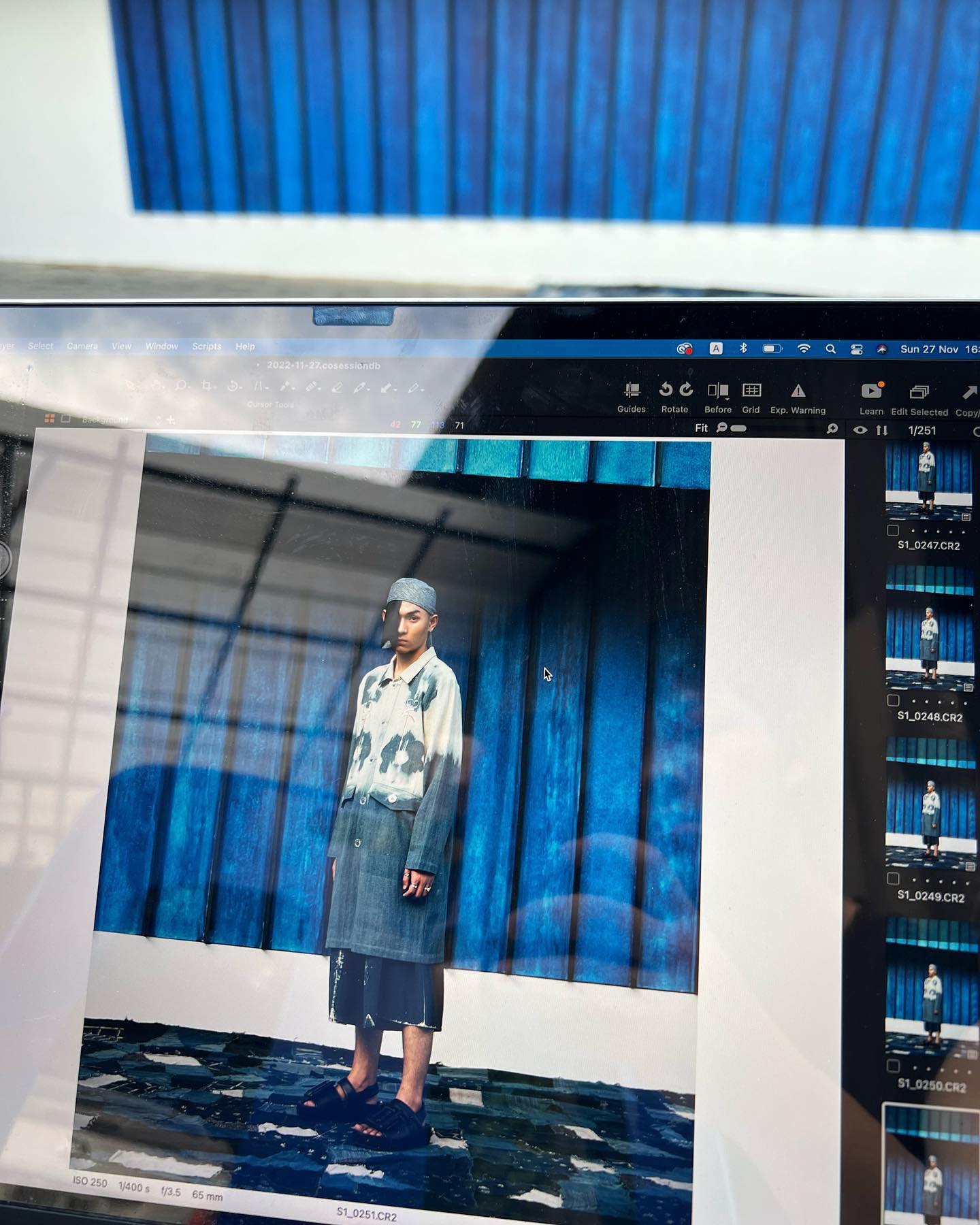

Sher Maker has always collaborated closely with local brands, as we’ve noticed. Patcharada stated that the outcome of each project has its own individual character, depending on the nature of the brand with which they collaborate. There are projects where they, as the project designer, must tone down their creative drive and focus more on issues that would better benefit the brands, like waste management or cost reduction. However, because LONG GOY is a design-oriented brand, the ideas that were proposed, such as the building’s colors, were taken up a notch by none other than the owner himself. As a result, the project ends up being even more unique than expected. This distinctiveness is clearly reflected in the catalogue of LONG GOY’s new collection, which uses the new building as a backdrop and captures the clothes and architecture as one beautiful and cohesive narrative.

Photo courtesy of LONG GOY