THE PHOTOBOOK COMPILED PHOTOGRAPHS RECORDED PROTESTS MOMENTS THAT ERUPTED BETWEEN 2020 AND 2022 IN THAILAND, GRADUALLY REVEALING THE EMOTIONS AND MILIEU FROM GOVERNMENTAL OFFICIALS SURROUNDING THE PEOPLE’S BATTLES

TEXT: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUL

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Korn Karava

Photographs by

Asadawut Boonlitsak

Peerapon Boonyakiat

Patipat Janthong

Tanakit Kitsanayunyong

Varuth Pongsapipatt

Natthapol Suebkraphan

Natthawut Taeja

Laila Tahe

Tanagon Thipprasert

Peera Vorapreechapanich

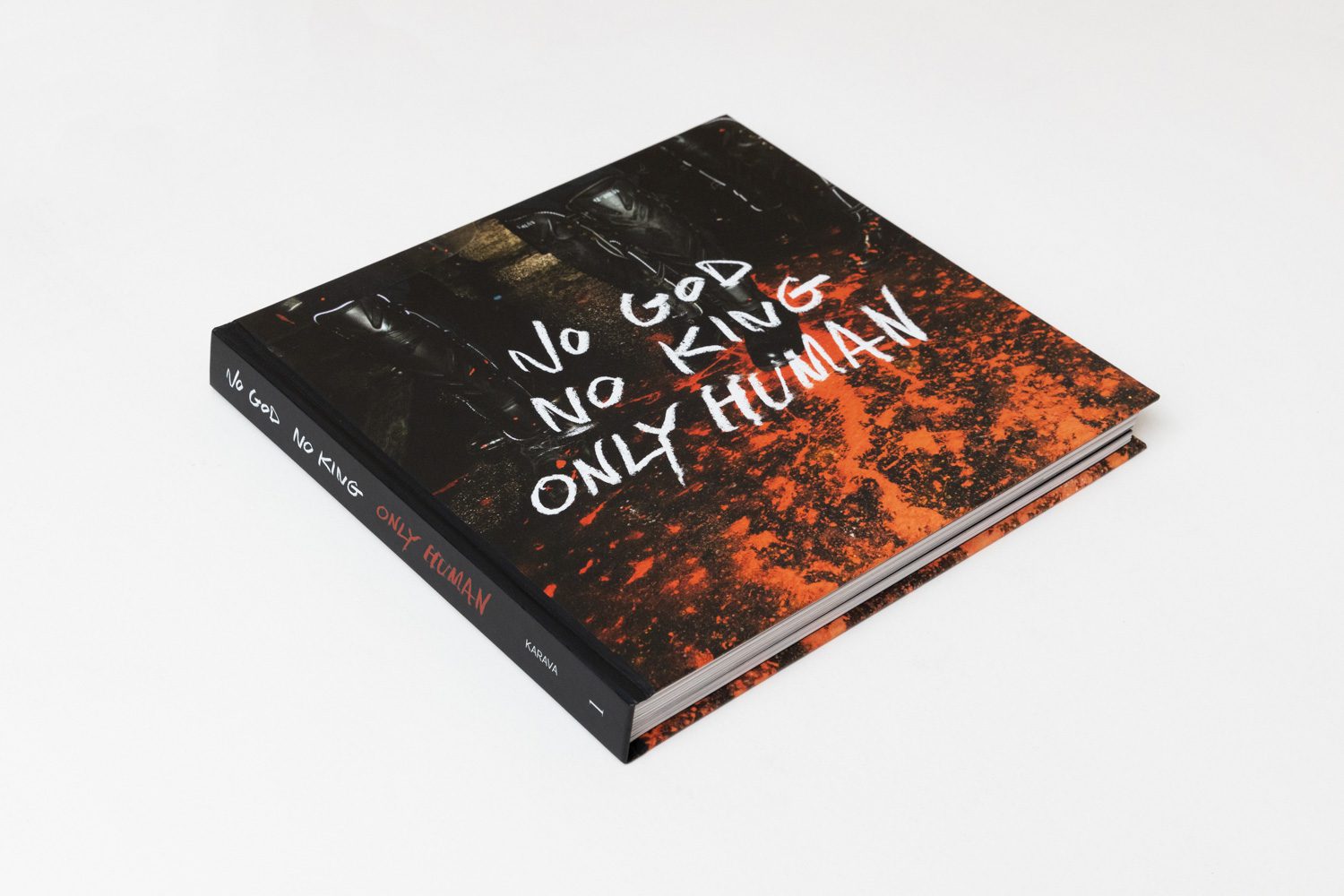

Karava publishing, 2022

24.6 x 23.1 cm

Paperback 192 pages

ISBN 978-616-594-230-0

After finishing this book, I wondered how I would explain this nearly two-hundred-page publication, which captures the history of the people—the common folk who took to the streets to fight injustice, especially since there isn’t a single word in it.

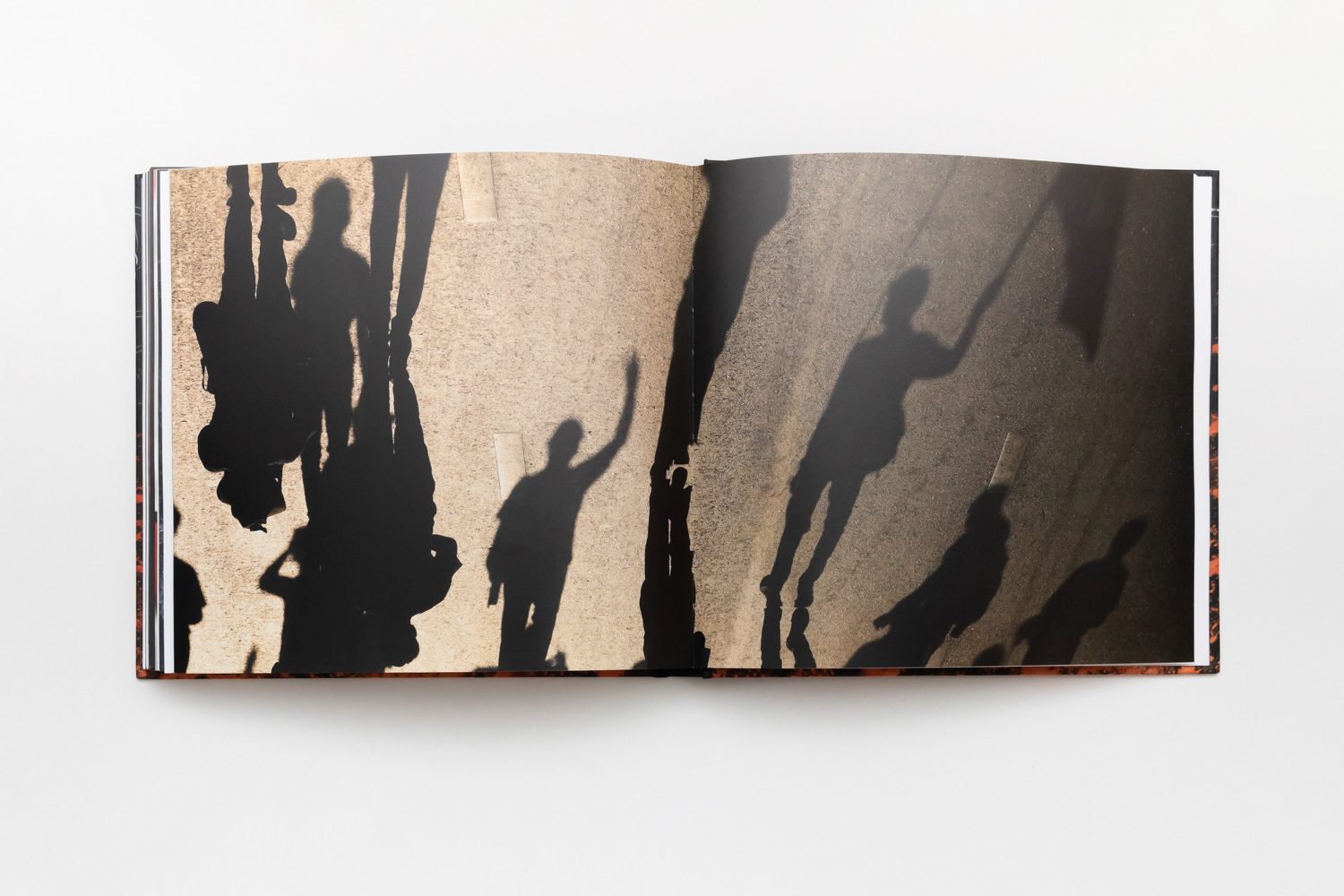

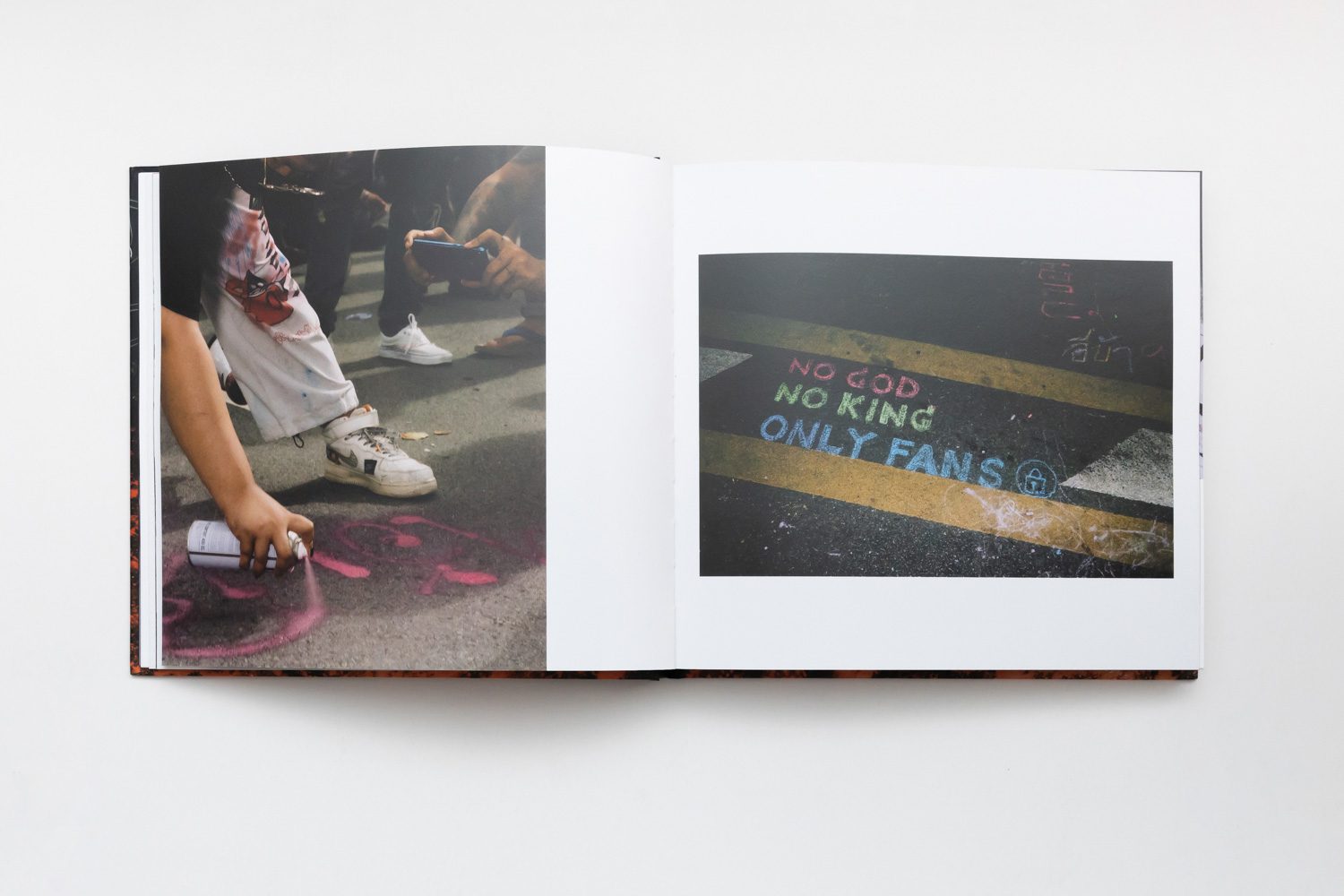

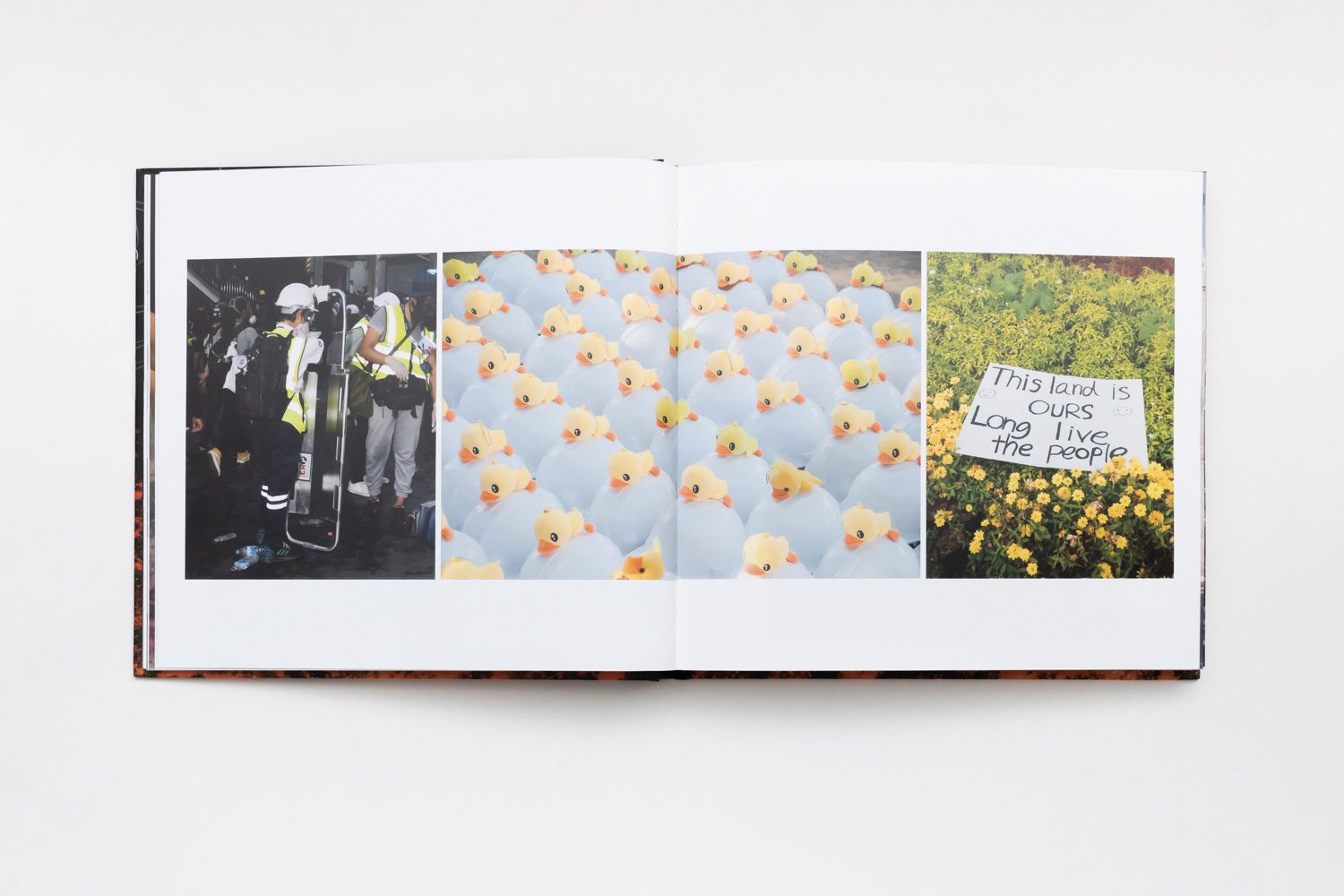

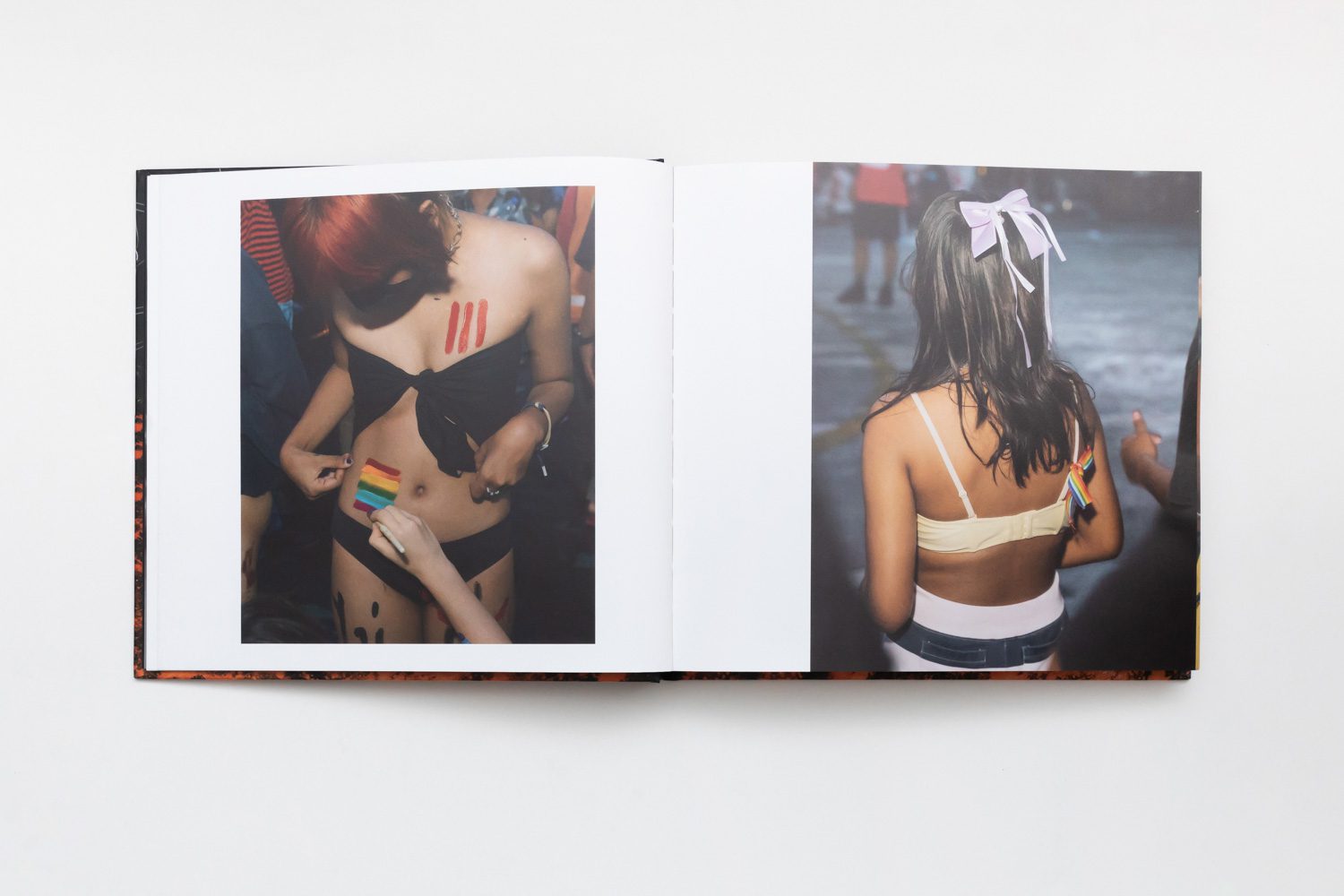

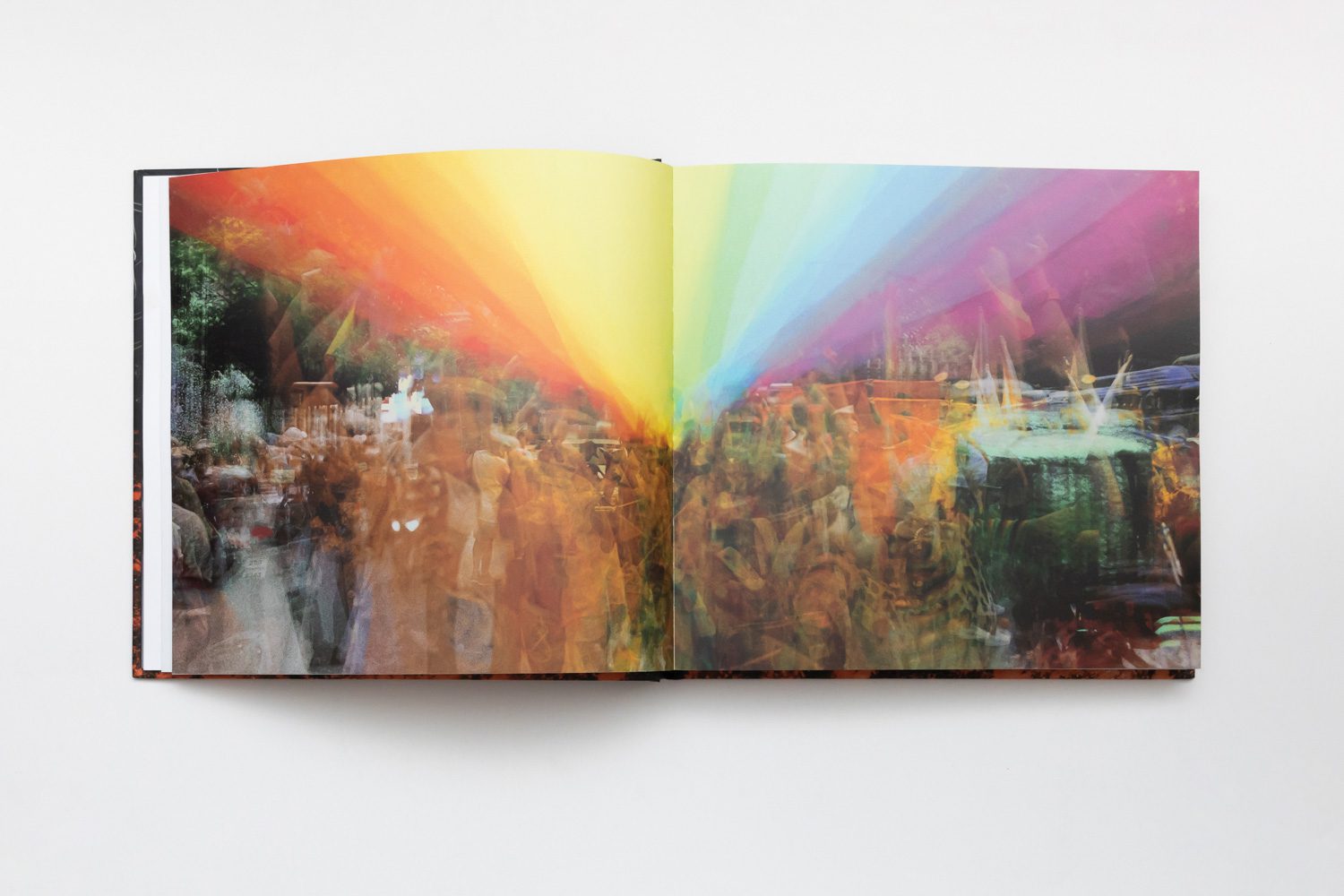

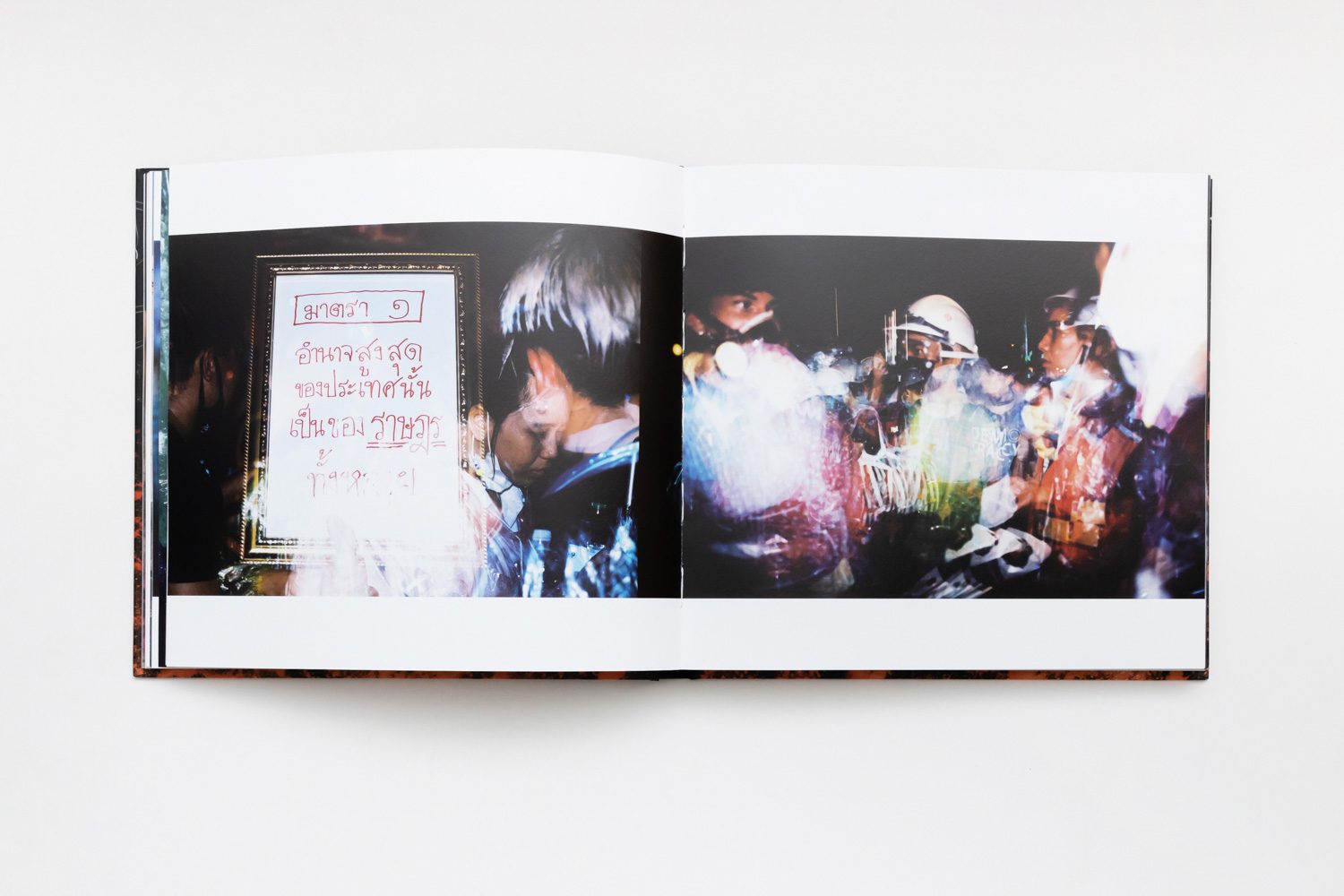

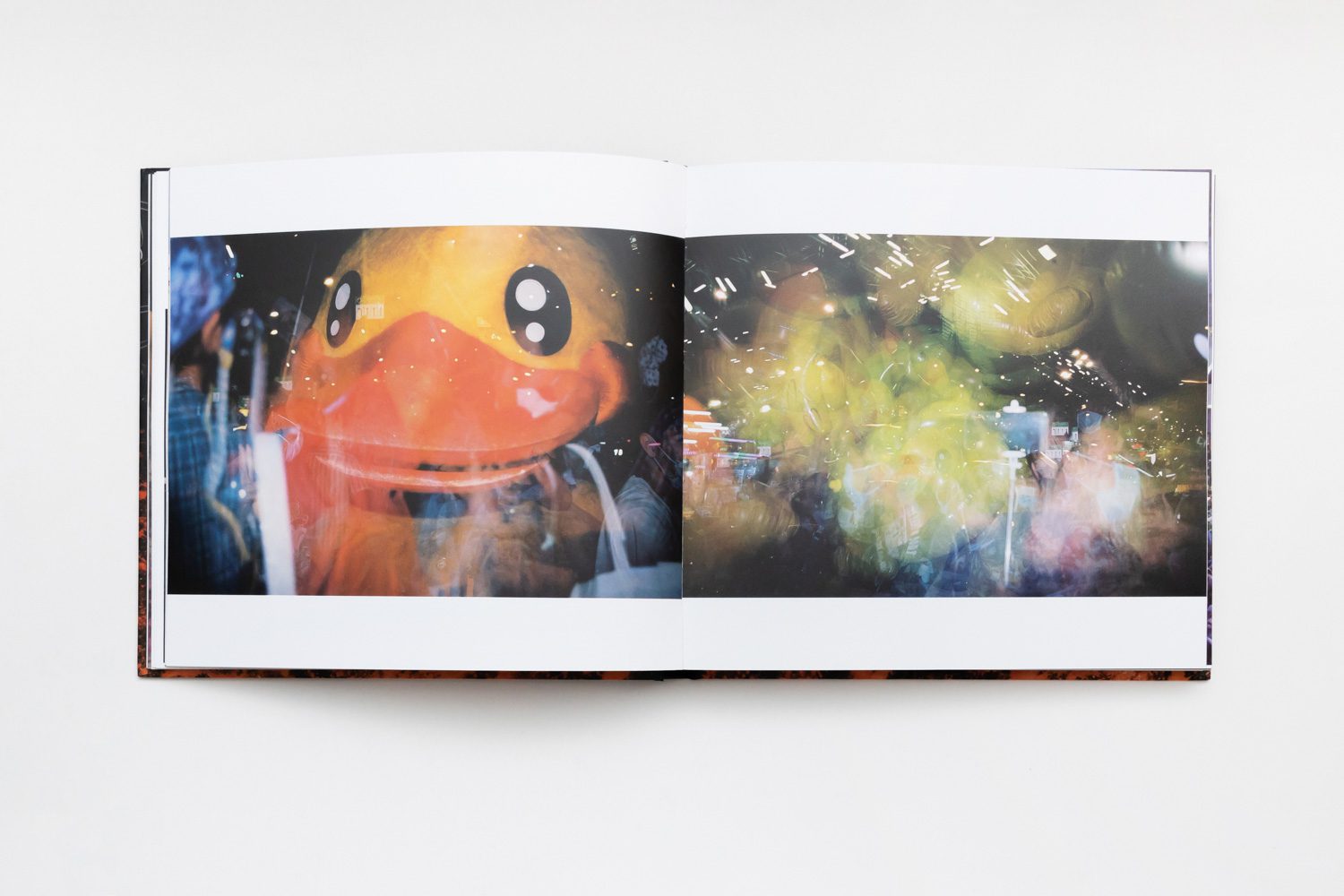

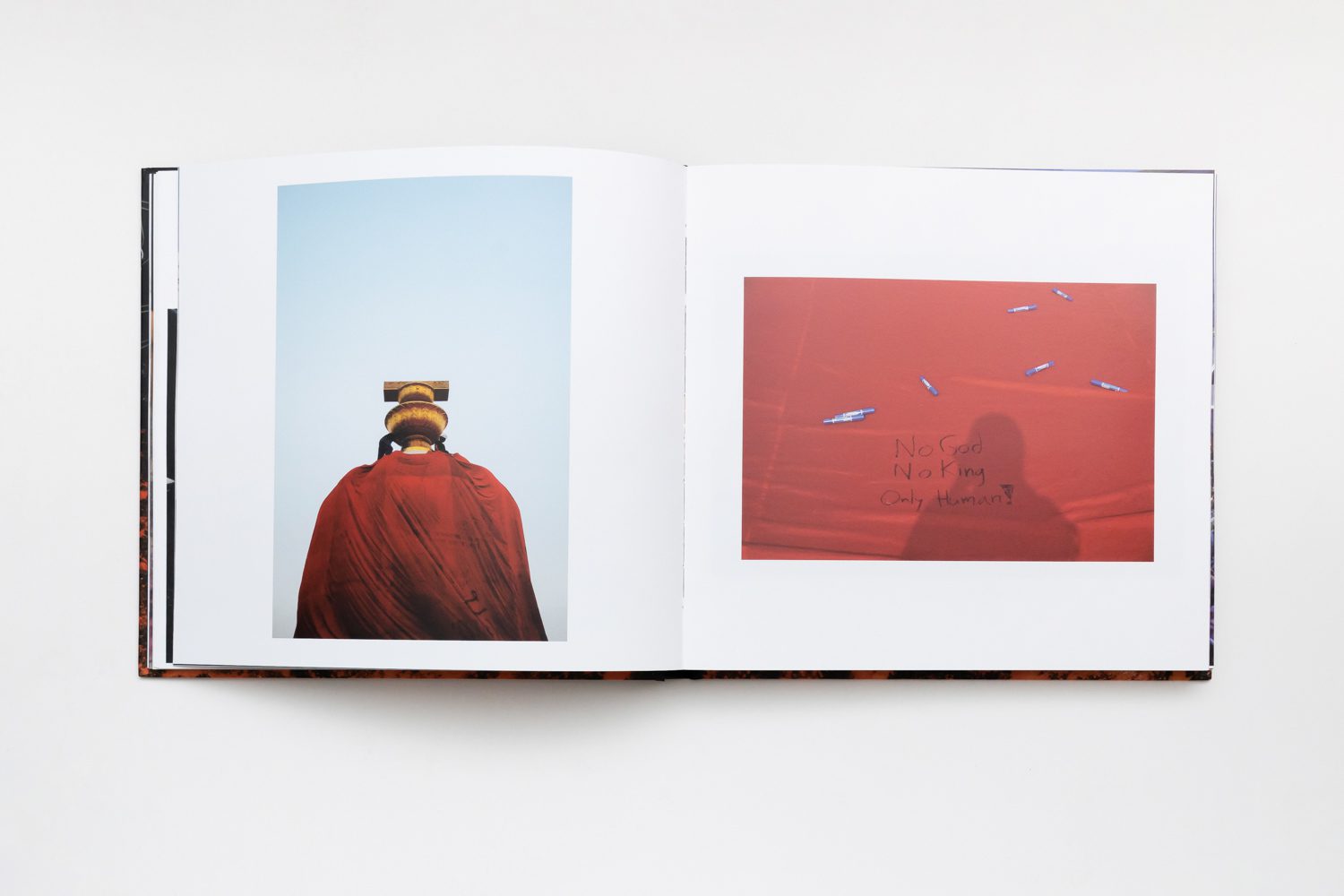

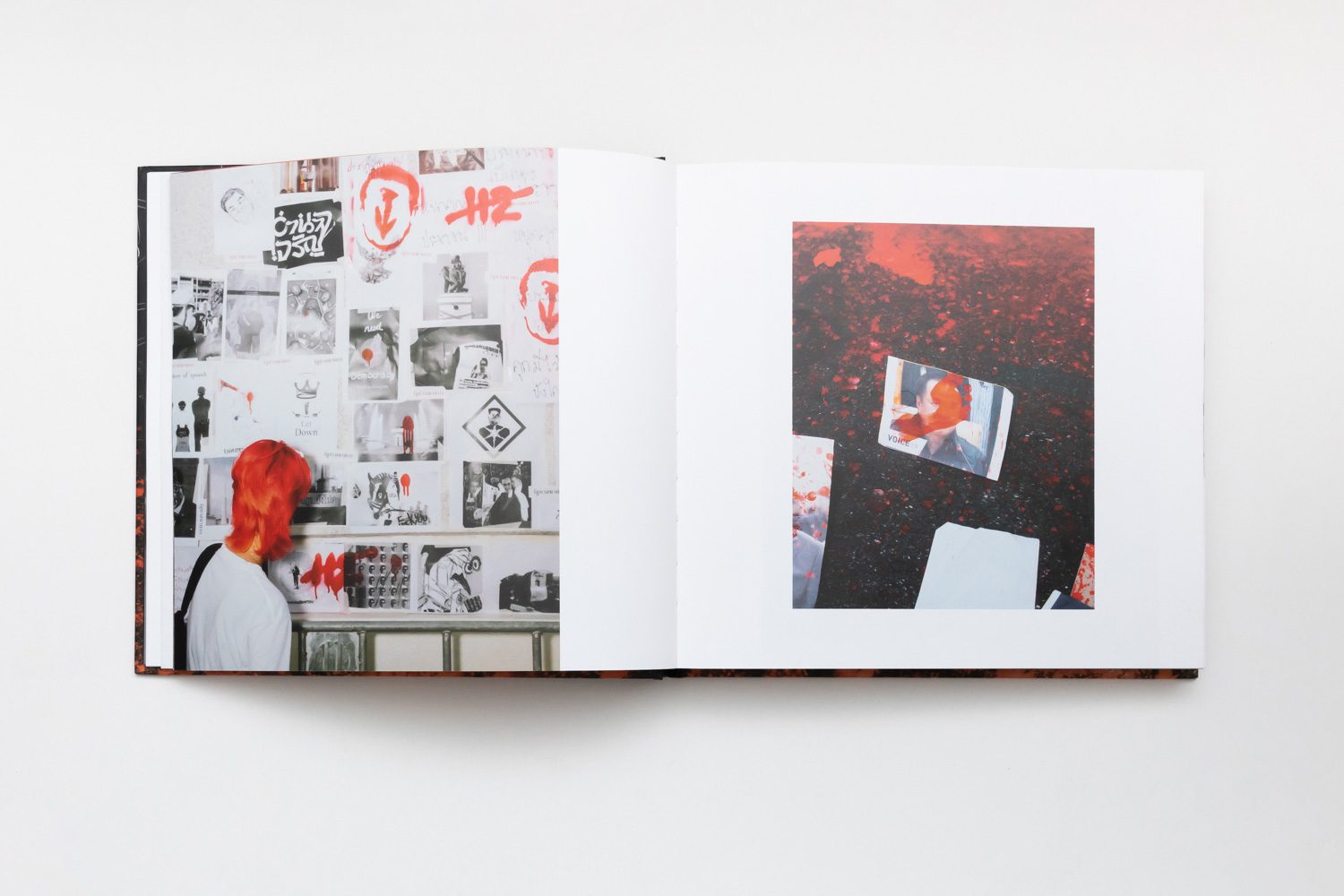

‘No God No King Only Human’ is a photo book published by Karava Publishing. The book compiled photographs by ten photographers who recorded moments and incidents that occurred during protests that erupted between 2020 and 2022 in Thailand. It was the period when people’s anger and frustration towards Prayut Chan-o-cha’s junta-in-disguise government, which was a direct product of the 2014 military coup, were at their peak. The already intense political climate was heightened by student-led demonstrations demanding monarchy reform, putting the hitherto taboo subject into the public debate and sphere. The phenomenon has transformed Thailand’s political landscape and social paradigm in unprecedented ways and sparked various demands ranging from gender equality to education reform. Not only does the book serve as an archive documenting one of the most monumental periods in Thailand’s history, but its photo book format invites readers to consider and contemplate the role of ‘photographs’ as a medium capable of transporting and delivering incredible masses of emotions and phenomena from actual locations where incidents occur. It also demonstrates how photos function and affect people in ways that go beyond the number of visible light wavelengths recorded by a camera’s sensor.

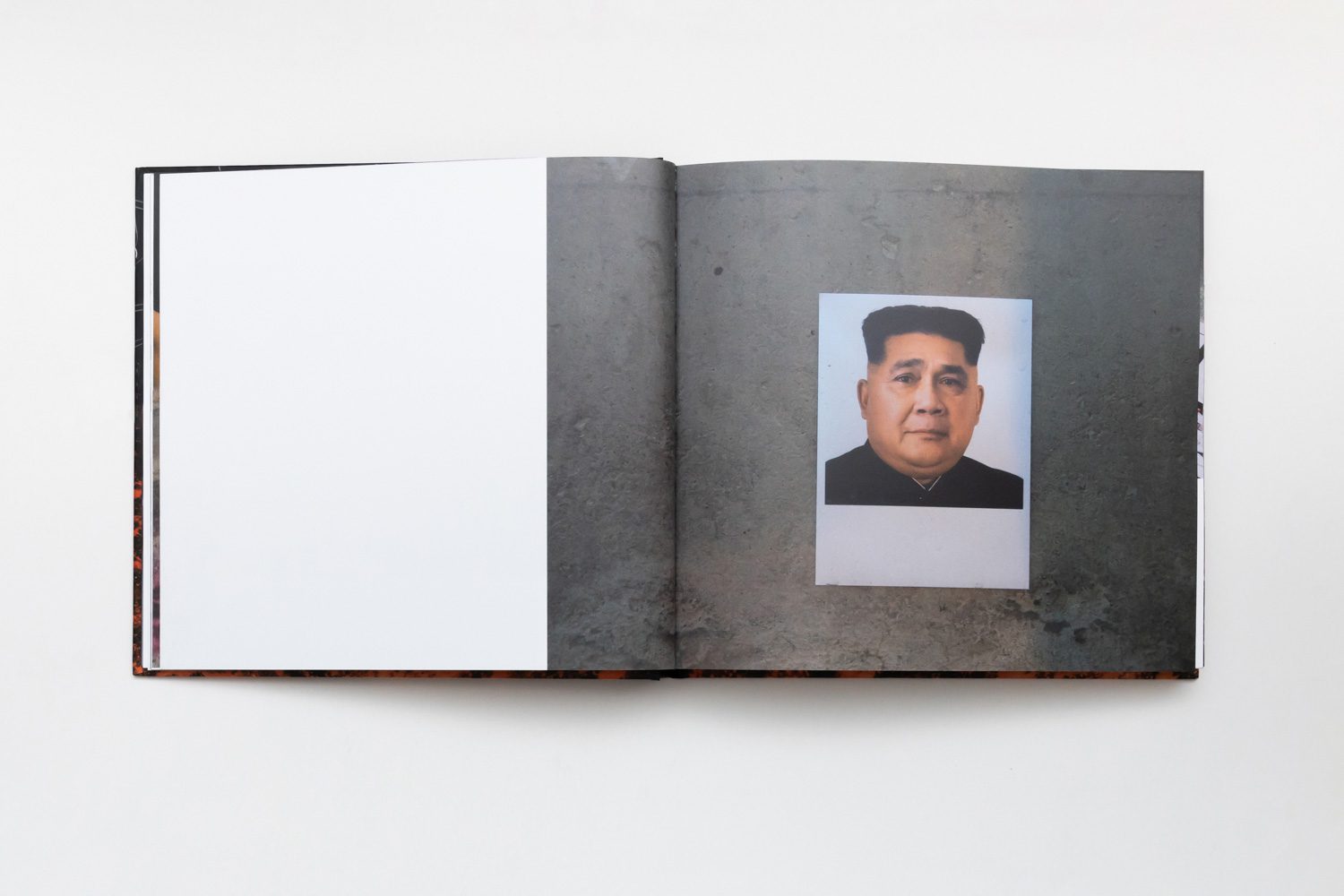

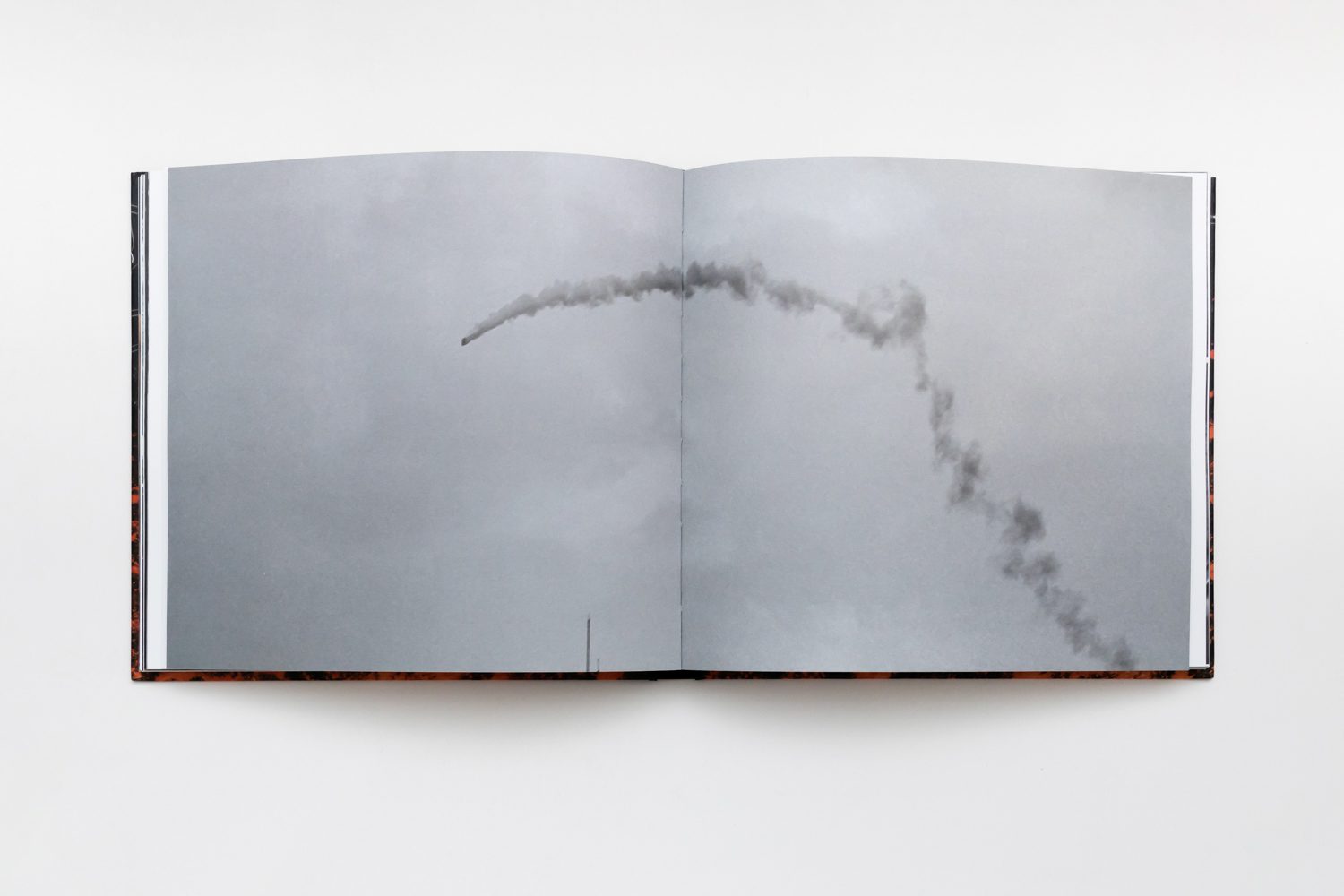

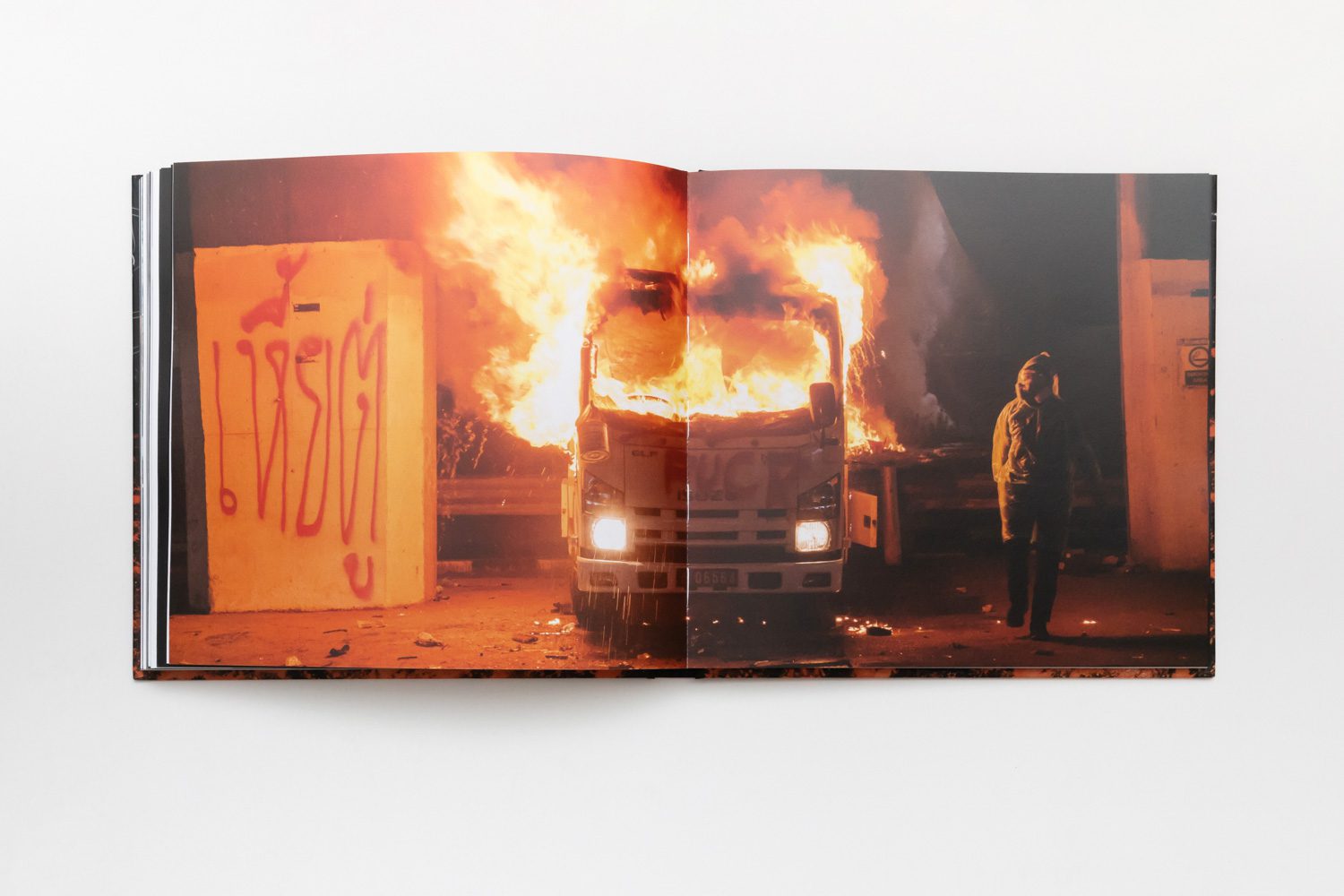

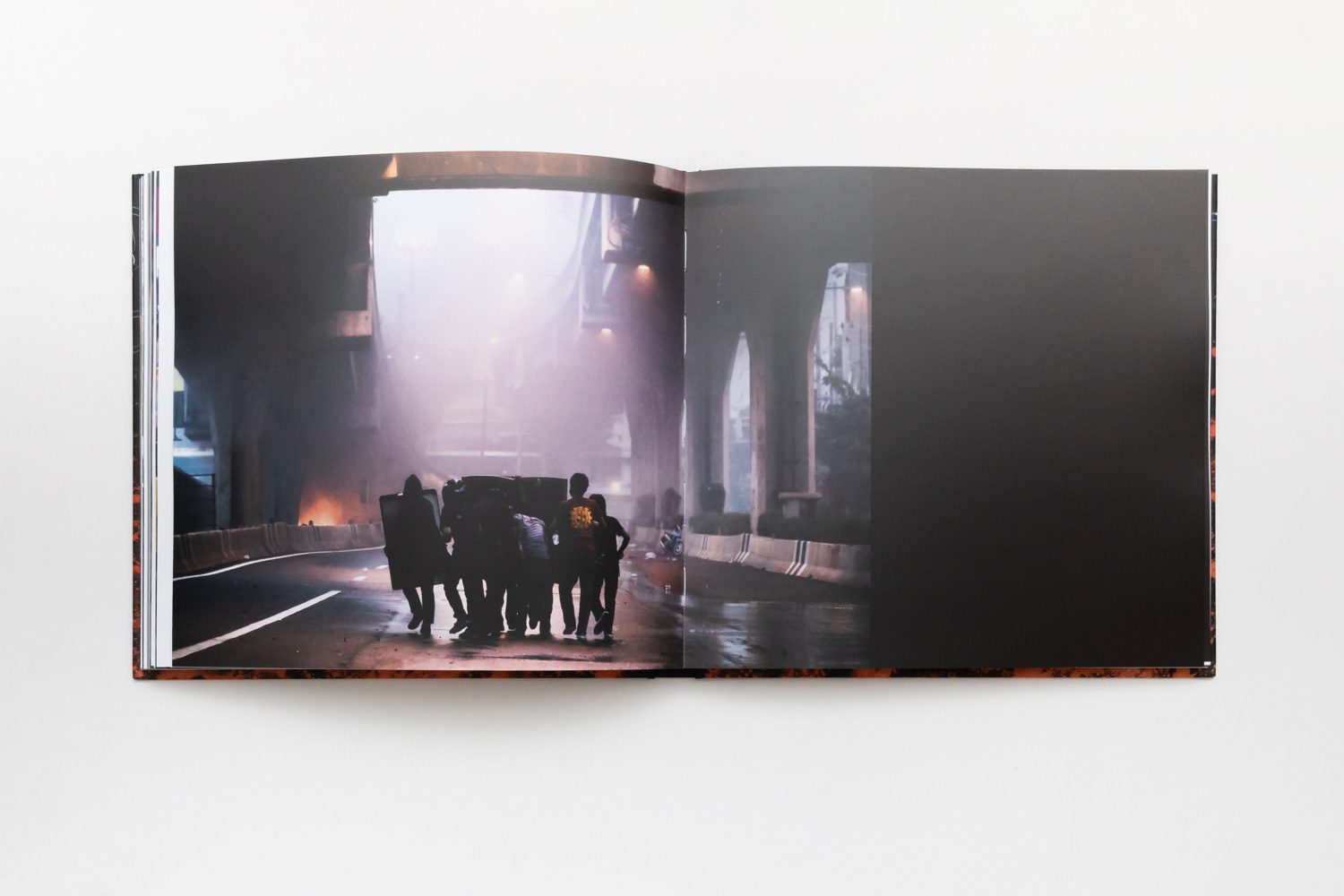

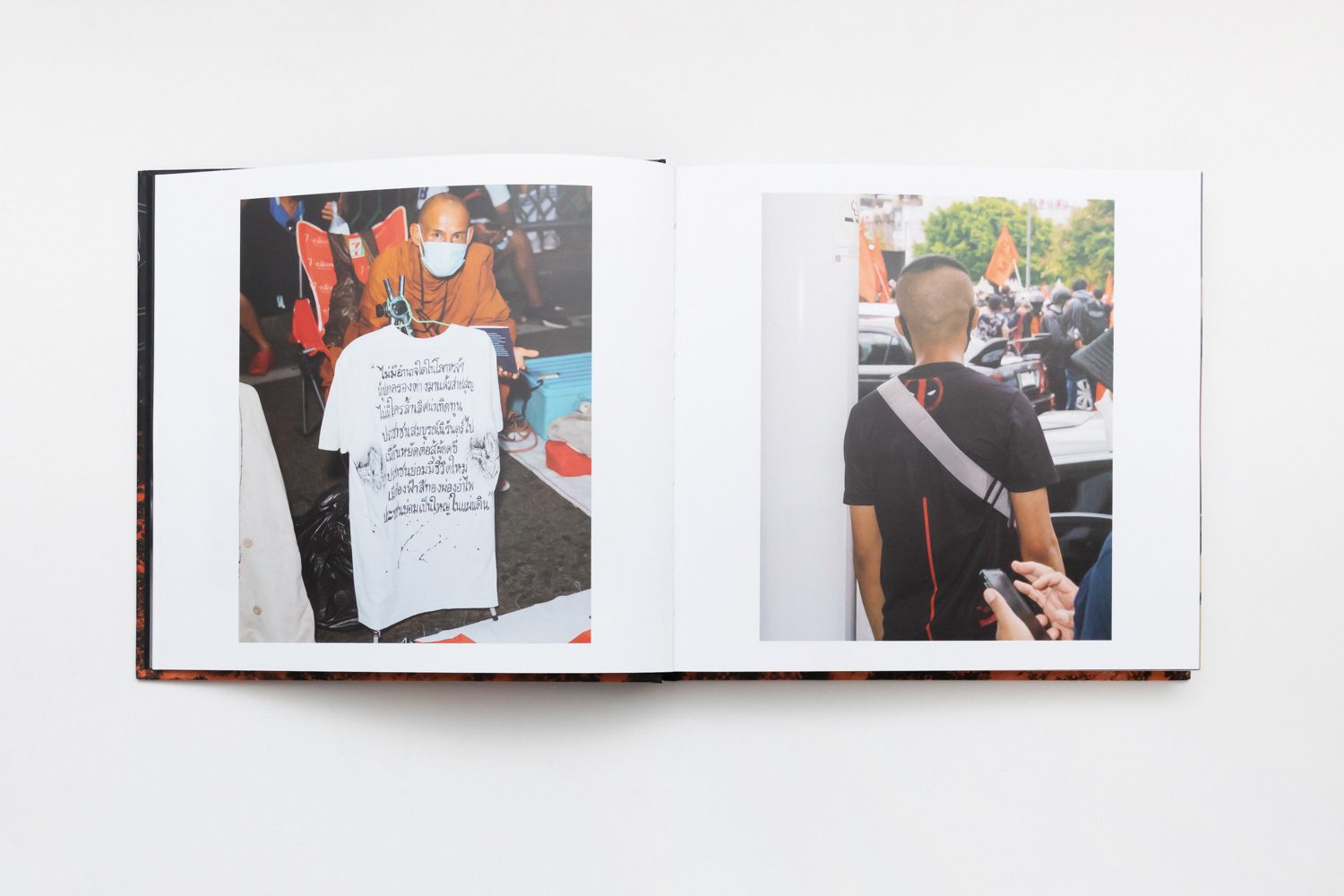

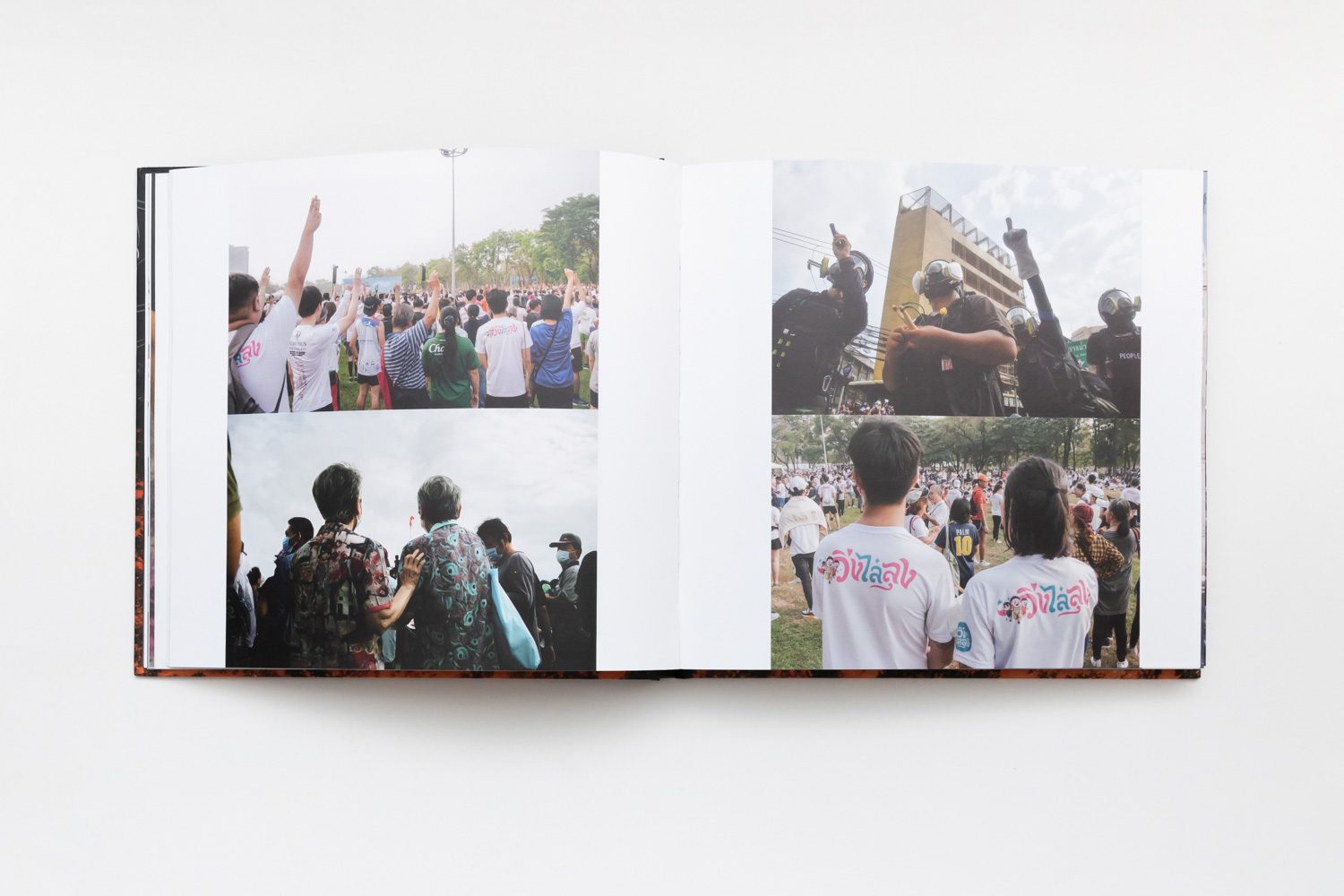

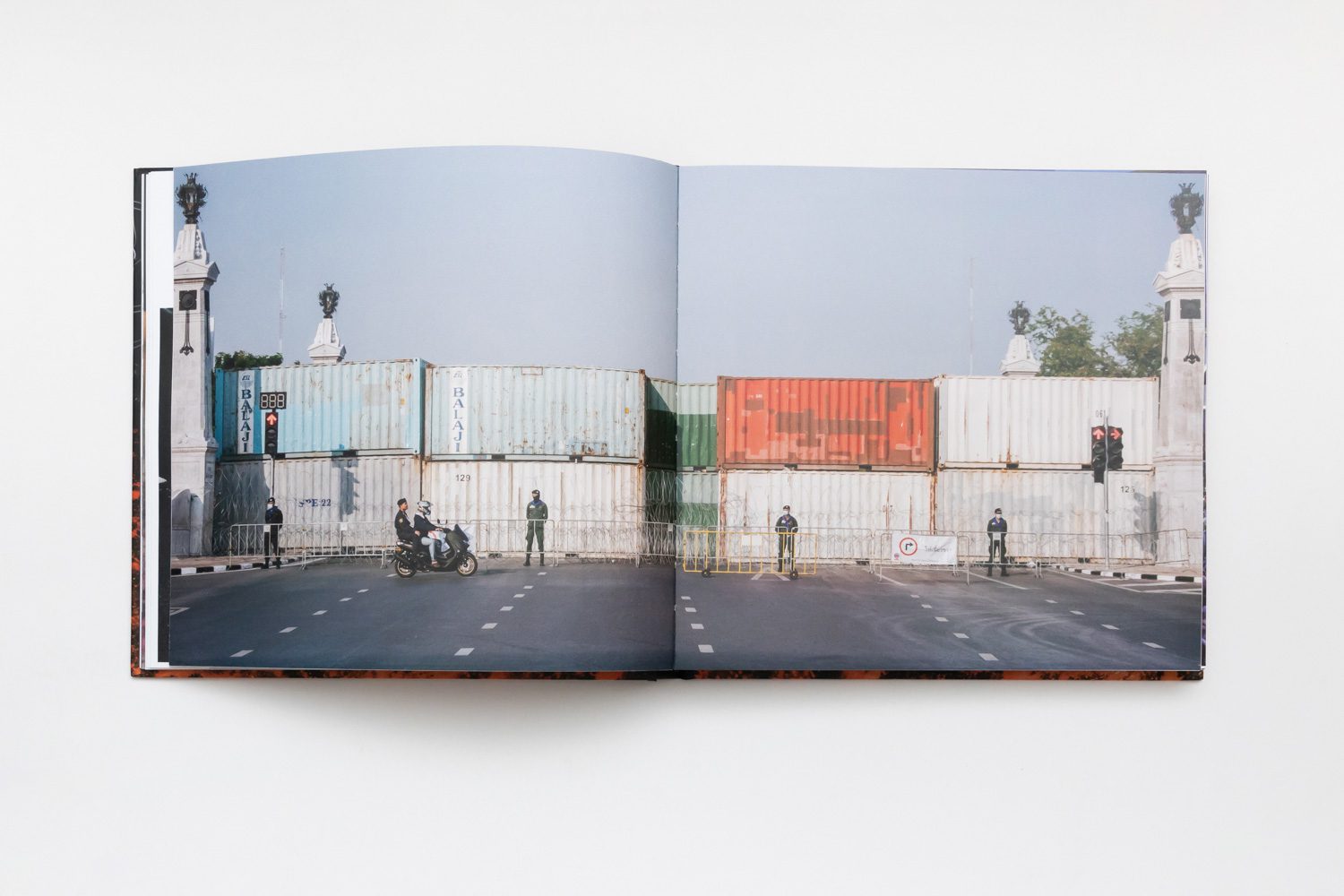

The book’s organization is not chronological, nor is it organized by the location in which the images were captured. It gradually reveals the emotions and milieu surrounding the people’s battles. It begins with photographs of less intense protests, such as the ‘Get Out Uncle Too’ running event (‘Too’ is Prayut Chan-o-cha’s nickname, while the ‘uncle’ moniker has been heavily publicized by the prime minister’s PR staff and followers, implying his kind and amiable attitude). The term was adopted as a means of derision by anti-government demonstrators. The book then takes readers through the more perilous protests where governmental officials and protesters clashed, such as the demonstration at Pathumwan Intersection, where riot police used water cannons to attack protesters for the first time, and other protests at Din Daeng Intersection, one of the most intense battlegrounds.

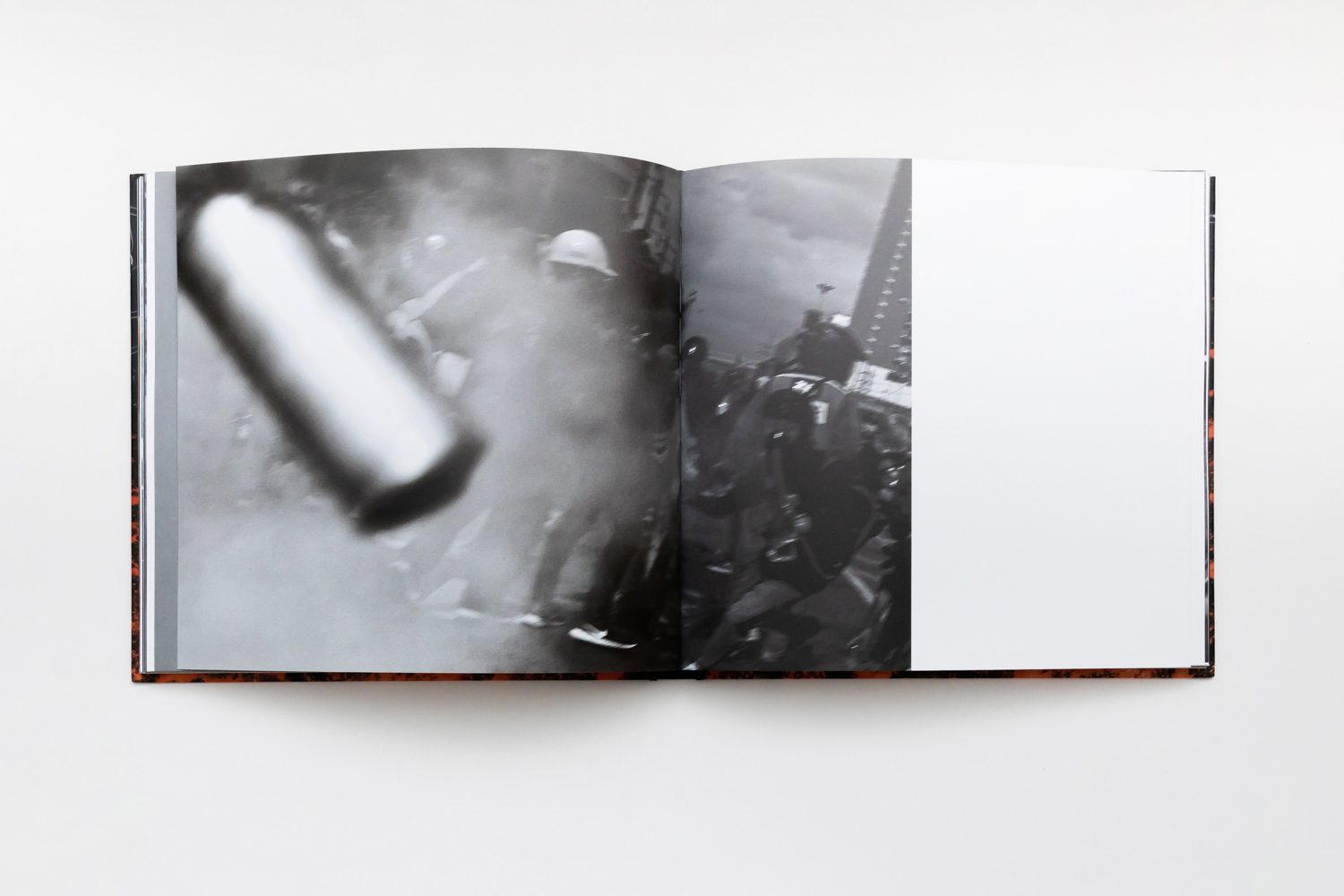

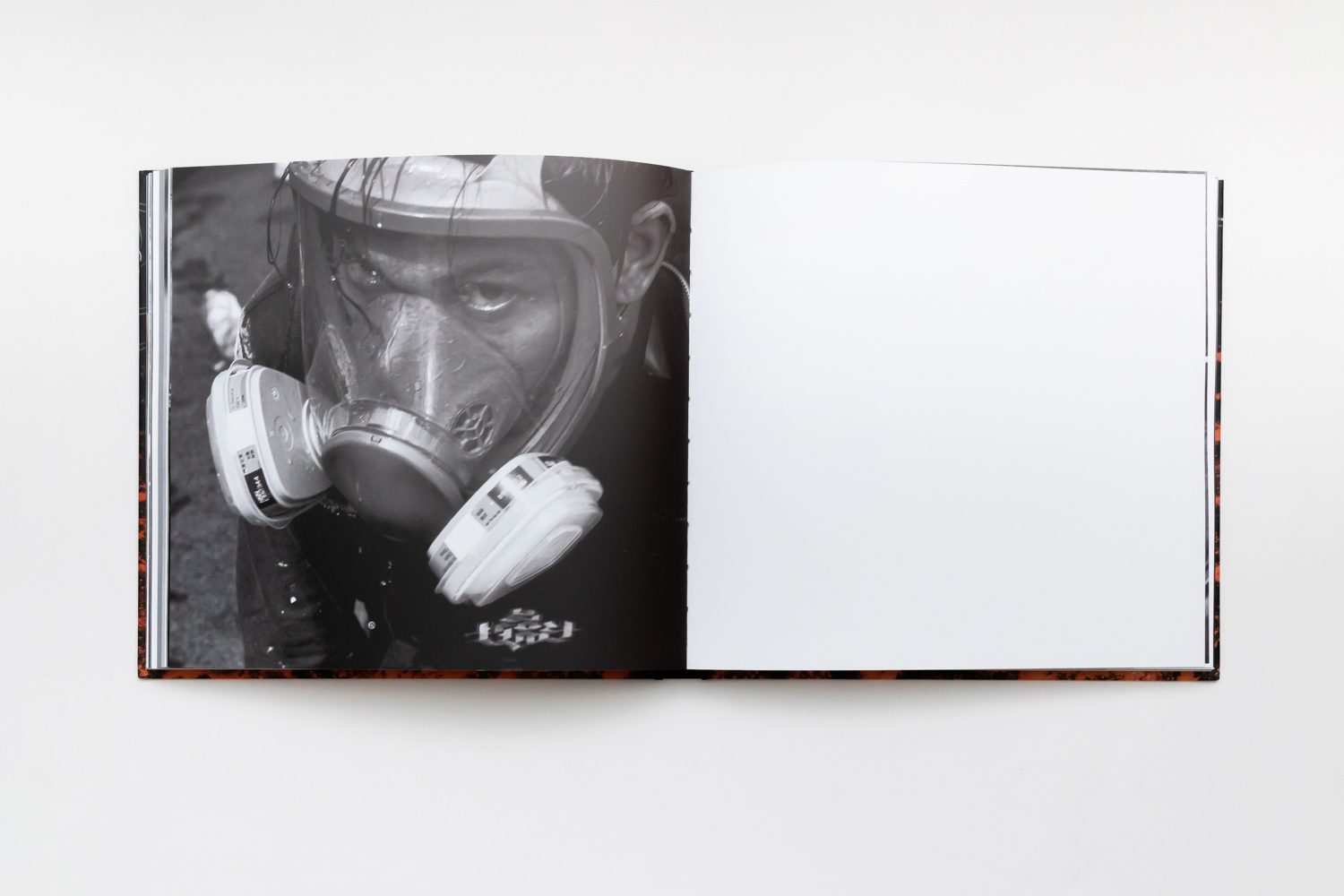

After reading the book for the third time, I realized that the ‘photographs’ were more than just a medium used to capture and convey the events and incidents that were part of the people’s ongoing battle. These photographs are, in and of themselves, a message. The manner in which each picture was taken illustrates the shifting definitions of people’s protests over time. People’s fights erupted in more verbal and symbolic forms during the initial protests. The protesters’ contents and actions were filled with a bit of humor and sarcasm. The photographs made during this time period are clear, with compositions that represent how the people who took them were given time to think and contemplate before taking a particular shot. But as the situation intensified, the meaning of these political protests changed and became associated with violence and unpredictability, filled with flames, people’s cries and screams, and brutality inflicted on innocent people by the hands of governmental officials in unimaginable ways. Many of the images taken during this time period are blurry and infused with a sense of urgency, possibly because the photographers, like the rest of the protesters, were attempting to survive the situation (the photographers and protesters are potentially the same people).

Another key point of the book became clear after I finished going through all the photographs of all the incidents that were captured. What was I supposed to feel from it? What should I do with what I witnessed? were the thoughts that popped into my head. Susan Sontag pointed out in her book ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’ (2003) that the process we devised to manage our emotions and feelings towards graphic images depicting violence happens through the way we think and contemplate about the origin and effects of a certain photograph we saw more ‘seriously’ than what we witness right before our eyes. ‘No God No King Only Human’ ‘s lack of textual descriptions and captions, the contents curated through page layout and negative spaces, and even their ‘Resistance Art’ status are all secondary details. The accounts of the fights and demands that shook long-standing institutions and the status quo, leading to violence and brutality, are what lie at the heart of the book. Such a core has encompassed other subsequent issues and events that have arisen as a result of the protests, ranging from the impunity of governmental officials to the unlawful and unjust enforcement of laws, to the day when these demands have found their way to the court and even the parliament, and have been discussed in a legal context and academic sphere. I wish for the readers of this book to remember when this great fight first began, on the street, by the youth and the common people, when these demands were met with bullets, when rain was turned into flames, and when people’s bodies became the last weapon they used to defend and fight for their own future.

No matter how many elections are held, I believe the fight will continue until the people’s wishes are fulfilled. Above all, this book serves as a reminder to us all that every change has its own origin, as stated in the quote on the final page—the only text featured in the book:

Without pain, there is thus also no revolution

No departure from the old, no history.

(Byung-Chul Han)

There are no heavenly blessings, no saviors, only individuals who continue to sacrifice their own future as they always have. Don’t forget to thank those who helped us get to the finish line, even if some of them are no longer with us to celebrate the great victory we, the people, will accomplish on the day when the change we all desire finally arrives.