‘Autumn at Phan Fa’ during Bangkok Design Week 2024 | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

ART4D HAS INVITED FOS LIGHTING DESIGN STUDIO, KNOWN FOR THEIR NOTABLE WORKS IN THAILAND, TO DISCUSS THEIR ROLE AS LIGHTING DESIGNERS, THE ENJOYABLE AND SIGNIFICANT ASPECTS OF THEIR WORK, AND THE CHALLENGES THEY HAVE FACED

TEXT: NATHATAI TANGCHADAKORN

PHOTO COURTESY OF FOS LIGHTING DESIGN STUDIO EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Light is often relegated to the background in the design process, even though we emphasize its importance as a functional element that makes spaces ‘usable.’ However, in terms of aesthetics, other architectural components seem to carry more weight, especially in projects with limited budgets and time constraints.

FOS Lighting Design Studio, a studio renowned for its outstanding work, to discuss their role as lighting designers. They have successfully executed remarkable projects such as the lighting and projection mapping for the Maensri MWA Office Building at BKKDW 2023, ‘Unfolding Hua Lamphong’ during the Unfolding Bangkok 2023 festival, and the lighting for the 101st anniversary of Phaya Thai Palace.

‘Autumn at Phan Fa’ during Bangkok Design Week 2024 | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Let us briefly introduce FOS Lighting Design Studio, a forward-thinking lighting design practice in Thailand. The studio was founded after the economic downturn by Thaneeya Yuktadatta and Diwan Khattiyakornjaroon. Thaneeya, initially an architecture student aspiring to advance her career, pursued a Master’s degree in Light and Lighting at University College London (UCL) and later interned with PALICON Pro-Art Lighting, one of the few lighting design studios in Thailand at the time. Thaneeya humorously but candidly notes, “First and foremost, let me warn you that I chose this career path thinking I could escape the intensity of architectural design—well, in reality, I haven’t escaped that at all.”

Thaneeya Yuktadatta | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

We started with the fundamental question—the inception of FOS Lighting Design Studio—about what motivated Thaneeya to establish her own company in an era when lighting designers were not widely recognized as mainstream professionals, coupled with an economy in Thailand that was less stable at that time

Thaneeya’s fascination with lighting did not arise from the outset. It didn’t occur before she chose her field of study or even after completing her education. The birth of her passion happened while working with PALICON, marking her initial realization of the distinction between having a lighting designer and not having one.

Sala Karnparien, Wat Phra Chetuphon Wimon Mangkhalaram (Wat Pho)

“That was the first time we saw a clear picture of its beauty. It was witnessing the image that everything I had done, all the exhaustion, was because of this. It was beautiful, serene, and quiet. Back then, ERCO was developing dark lighting that created a visually soothing lighting effect. Anything that needed to stand out did, and I vividly remember the most impressive image—a bathtub with backlighting behind it. In reality, it was quite a small detail, but it made the entire ambiance look much more inviting and appealing. That was the first image that made me feel like, ‘This is it’.”

“As time went on, I encountered limitations regarding specifications because, when working with ERCO, I could see how incredible their products were. But there came a point where I felt like I wanted more freedom in terms of what I was going to use. So, I started working on my own as a freelancer with another colleague, Diwan. Eventually, we founded FOS Lighting Design together, a name coined by one of our friends from school, as FOS translates to ‘light’ in Greek.”

Phra Phuttha Maha Mongkol at Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahidol University

We proceed to ask Thaneeya about her experience as a lighting designer at FOS Lighting Design Studio over the years, especially given its status as a trailblazer in the field, and which projects have left a lasting impression and why.

Thaneeya responds that the most impactful works are those involving sacred, religious spaces rather than commercial projects. This distinction arises from the different design philosophies and collaboration dynamics involved. Thaneeya asserts that everyone involved in such projects, from owners to stakeholders and contractors, is collectively driven to ensure the final outcome of the highest quality. This collaborative spirit sets sacred space projects apart from other types of work.

“There’s another project I particularly enjoyed. I had the opportunity to work on the National Museum Bangkok once. To me, this project was impressive because it allowed me to apply theories I extensively studied during my academic studies. The materials were highly sensitive, and I had to devise efforts to evoke the mood of the artistic artifacts. It was a challenging but incredibly fun experience.”

National Museum Bangkok

National Museum Bangkok

National Museum Bangkok

While Thaneeya’s studies at UCL emphasized theory and research, practical experience became crucial for a deeper understanding before effectively applying the acquired knowledge. The National Museum Bangkok project can be described as a job that demanded a well-rounded arsenal of both knowledge and experience.

The difference in designing lighting for sacred spaces and museums is not limited to the type of space alone. Even within the realm of installations in sacred spaces, the approach varies. Religious artifacts in museums are not as bound by religious ideologies, but in the design process, the essence of ‘sanctity’ remains a crucial and necessary end result, while there are other site-related factors that also play a significant role.

National Museum Bangkok

A draft for lighting design at National Museum Bangkok

But these are not the only projects that have personally stood out to Thaneeya. Bangkok Design Week and Unfolding Bangkok, especially in the past few editions, stand out as two festivals she has thoroughly enjoyed almost every year. For Bangkok Design Week 2018, it served as a starting point that brought together Thai lighting designers, including herself, under the name Lighting Designers Thailand (LDT). This collective, initiated by Maez Bhucharoen, started off with a project called The Wall 2018 in the Talat Noi area of Bangkok, followed by The Wall 2019 at Scala Cinema, and finally, The Wall 2022 at Khlong Padung Krung Kasem Canal.

Her impression of these projects has a backstory. It’s crucial to mention that during her master’s degree, Thaneeya’s thesis was on urban imageability theory by Kevin Lynch. This academic background resonated with her work as a lighting designer and her dream to work in all types of spaces. And Bangkok Design Week provided an ideal platform.

“I have a special love for Bangkok Design Week 2019 at SCALA. I felt it deeply because I could illuminate both the interior and exterior of architectural components. I wanted to see the structure come alive once again. I wanted people to appreciate the architectural beauty through light, to the extent that they would not want to demolish the building. Unfortunately, the event didn’t receive much attention, and it was regrettable that Scala was eventually taken down. As for Khlong Phadung Krung Kasem Canal, while it was somewhat more like a social event, it also had elements of urban lighting in the architecture. So, I had the chance to design lighting that was integrated into the city’s fabric,” she emphasizes.

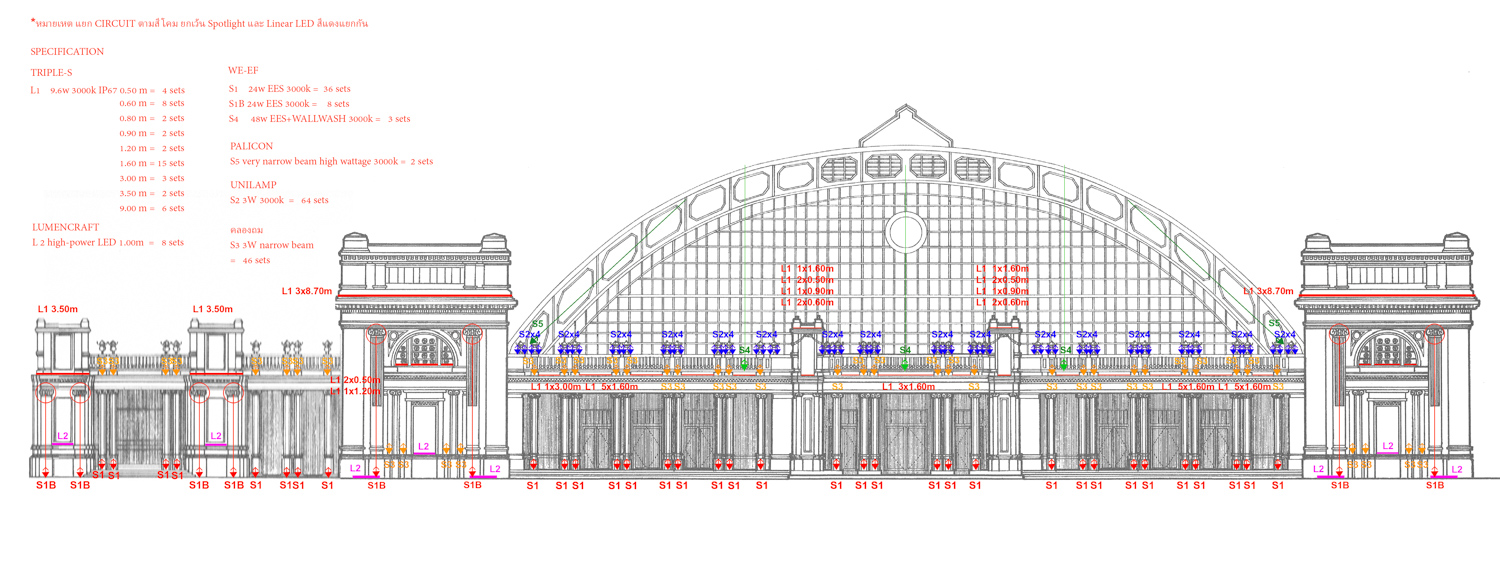

Apart from these aforementioned works, there’s another project under LDT that left an impression on her: Unfolding Hua Lamphong in Unfolding Bangkok 2023. The project involved designing temporary lighting for the Hua Lamphong train station, the long-standing train station that everyone is familiar with. By dividing the site into three zones: the front, the waiting hall, and the walkway, the lighting design for each zone considered the architectural aspect of a functional space rather than merely showcasing the station as a piece of installation.

Hua Lamphong during Unfolding Bangkok 2023

“The concept remains the same; there must be elements of architectural lighting, meaning lighting that enhances the architecture. Still, there must be something that attracts people, like the lighting effects used in social events or exhibitions. The architecture doesn’t exist in isolation; there have to be people, activities, and usage. Ultimately, when the project is complete, I have to express gratitude toward the people who participated in it, because them being there showcased the potential of the space, proving that, aside from being an old train station, it could serve many other purposes.”

Hua Lamphong during Unfolding Bangkok 2023

Having reached this point of the conversation, we took the opportunity to ask her about the difficulties and challenges in the field of lighting design.

“The Hua Lamphong Station project was challenging. One aspect is the sheer scale of it; when you walk around, it’s so vast that it can be overwhelming. If you want to make it successful within this budget, with this number of people working and this timeframe, just thinking about it can be stressful,” reflects Thaneeya on common challenges that many in the industry would understand well. “Also, it’s challenging due to lighting technology. It’s not like architecture, where changes happen slowly. Lighting equipment changes rapidly. It was like a certain way last year, and now it’s different. We have to keep up with the pace. That’s the challenge of technology, which requires us to learn endlessly. Event organizations are mostly challenging due to time constraints.”

Various limitations were revealed through work experiences, including something as basic as design specifications.

“Light isn’t exactly tangible. It is not something you can easily grasp. It cannot be described in words that everyone will mutually understand. Suppose we’ve gone through the design phase with the contractor. They see the design and check the numerical values of the light angle and color temperature, comparing them accurately. But even with the same numerical values, the lighting may not look the same. Or when we talk about warm light, there’s a big range to warm; is it yellow, pink, or orange? This is tiring, especially in government projects that strictly adhere to written specifications when we cannot exactly specify light in words,” Thaneeya narrates.

Phra Ubosot, Wat Suthat Thepwararam Ratchaworamahawihan (Wat Suthat)

Phra Ubosot, Wat Suthat Thepwararam Ratchaworamahawihan (Wat Suthat)

Phra Ubosot, Wat Suthat Thepwararam Ratchaworamahawihan (Wat Suthat)

What is your view of the role of lighting designers in the current Thai design scene? We asked Thaneeya the concluding question, considering that she is someone who has witnessed changes happening throughout her career. And she eagerly shared her insights.

“Nowadays, it seems there are more people working in this profession. When I first started, there were like ten or so of us practicing the field. I feel that more people have been acknowledging the importance of lighting design. It might reflect that this profession is becoming more in demand. However, there are still conditions attached to it. A project owner who wants to incorporate lighting must recognize the significance of lighting, first and foremost. They need to want their projects to have beautiful lighting and allocate a budget for it. Because when lighting designers choose equipment, which comes with certain conditions, not everyone is going to get on board. It’s impressive if a project owner appreciates our (lighting designers’) contribution and decides to use what we suggest. Because ultimately, it all leads to the same successful goal.”

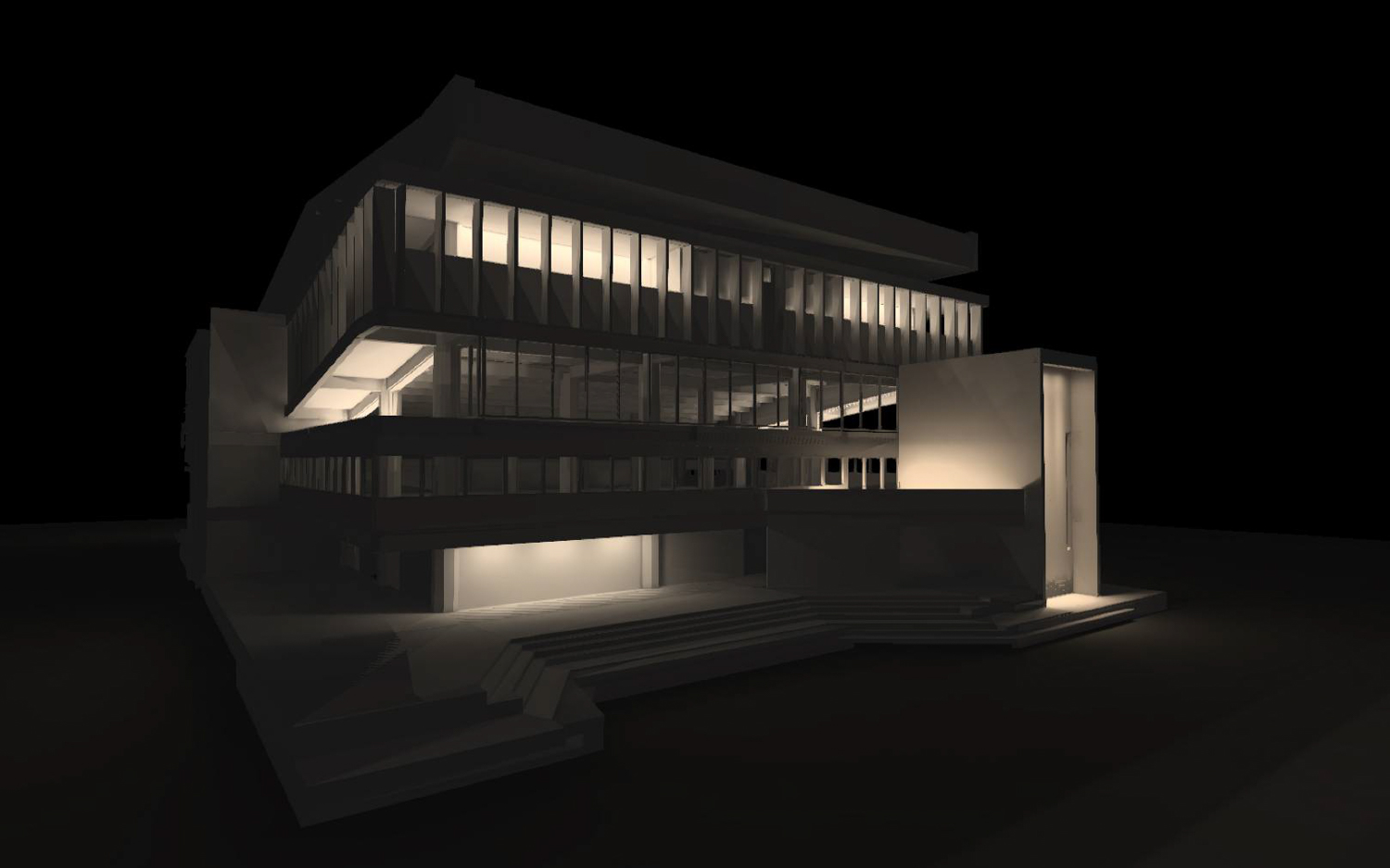

A draft for lighting design at the Hall, Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra campus

The Hall, Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra campus

The Hall, Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra campus

“At the end of the day, what I want to point out is that, in reality, having a lighting designer or not doesn’t make much difference. There are people who may think that this is already enough, maybe similar to my mindset before I started developing a serious passion for lighting design. But once you experience it, you will understand the importance of light on your own. These days, I think that everyone in this field of the profession is trying to establish that kind of mindset in order to prove themselves. This is a relatively new profession. Even though it’s not that new since I’ve been working for about twenty years now, it’s still going to take more time to see how everything will evolve and unfold.”

The Library, Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra campus

The Library, Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra campus

Every space requires light, extending beyond the pragmatic necessity for visibility and functionality; it unveils the next level of beauty that can be meticulously designed. As we ponder Thaneeya’s insights, it becomes apparent that, within the current landscape, every lighting designer is fervently crafting their own light, endeavoring to propel this profession into uncharted territories—stepping out of the veiled and frequently underestimated shadows that have obscured its true impact.