AFTER 5 YEARS WORKING AS A DESIGN CONSULTANT FOR OTHER BRANDS, SARNGSAN NA SOONTORN LAUNCHED ‘JAOBAN’ IN ORDER TO CREATE LITERAL AND THEORETICAL CRAFTED PRODUCTS

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PORTRAIT: SAROENGRONG WONG-SAVUN

PHOTO COURTESY OF MOK KAM POR

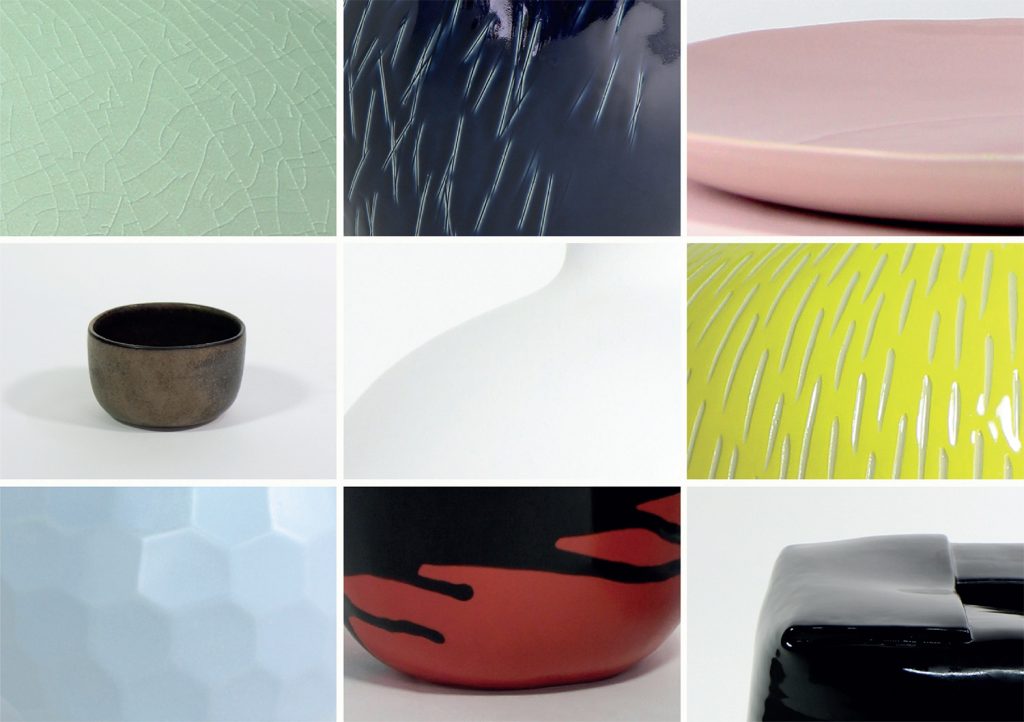

Artistic Direction for Prempracha’s Collection in 2014

JAOBAN เป็นแบรนด์เฟอร์นิเจอร์งานคราฟต์ที่เปิดตัวขึ้นใน ปี 2016 โดยสร้างสรรค์ ณ สุนทร ดีไซเนอร์ชาวเชียงใหม่ที่ในเวลานี้ใช้ชีวิตและทำงานอยู่ที่ฝรั่งเศส “ตอนนี้ข้างหลังแบรนด์ JAOBAN มีแค่ผมคนเดียว JAOBAN เป็นโปรเจ็คต์ที่ผมทำขึ้นมาเพื่อทดสอบแนวโน้มของงานคราฟต์เชียงใหม่ในตลาดโลก ยิ่งตอนนี้พ่อแม่เริ่มแก่แล้ว อีกไม่นานผมน่าจะต้องกลับไปดูแลกิจการที่บ้าน” ครอบครัวของสร้างสรรค์เริ่มต้นกิจการงานฝีมือตั้งแต่พ่อของเขาที่เคยเป็นครูประชาบาลอยู่เชียงรายย้ายมาประกอบอาชีพขายของจักสานในเชียงใหม่ ก่อนจะเขยิบมาขายไม้แกะสลักเล็กๆ น้อยๆ จนถึงปัจจุบันที่ประกอบธุรกิจไม้แกะสลักอย่างเต็มตัว

“ชีวิตวัยเด็กของผมเติบโตมากับของเหล่านี้ โดยเฉพาะตอนเรียนสถาปัตย์ที่มหาวิทยาลัยเชียงใหม่ ที่ผมซึมซับเรื่องความเป็นพื้นถิ่นมาจากอาจารย์จุลพร นันทพานิช มากทีเดียว” ถึงแม้ว่าจะจบมาด้านการออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรม แต่สร้างสรรค์กลับไม่ได้ตั้งเป้ากับตัวเองว่าจะเป็นสถาปนิกแม้แต่น้อย อาชีพที่เขาคิดไว้ในหัวตอนนั้นคือการเป็นนักกิจกรรมสิ่งแวดล้อม (น่าจะเป็นอิทธิพลที่ได้จากอาจารย์จุลพร ที่ทำกิจกรรมเคลื่อนไหวเรื่องสิ่งแวดล้อมมาอย่างต่อเนื่อง) แต่ก็พับความคิดนั้นไป เพราะมองว่าการทำอะไรสเกลใหญ่ๆ ที่เกี่ยวกับเมืองน่าจะต้องเอาตัวเองไปเกี่ยวข้องกับกฎหมายหรือนักการเมืองอยู่ไม่น้อย “พอเราไปฝรั่งเศส ด้วยความที่เราตั้งใจจะเปลี่ยนสายจากสถาปัตย์มาแต่แรกแล้ว เราเลยเลือกเรียนด้านการออกแบบอุตสาหกรรมแทน ตอนนั้นเราคิดว่าอยากลดสเกลการทำงานจากออกแบบอาคารใหญ่ๆ ที่ต้องใช้เวลานานกว่าจะเอาไอเดียในหัวทำออกมาเป็นรูปธรรมได้ มาทำงานชิ้นเล็กๆ อย่างการออกแบบอุตสาหกรรมที่จบงานได้ด้วยตัวคนเดียว”

สร้างสรรค์เรียนออกแบบอุตสาหกรรมที่ ENSCI-Les Ateliers อยู่ 3 ปี พอเรียนจบก็ทำงานเป็นดีไซเนอร์ให้กับสตูดิโอในปารีส อย่างเช่น Gabriele Pezzini, Constance Guisset Studio และ Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec ก่อนจะถูกดึงตัวกลับไปเป็นอาจารย์พิเศษที่ ENSCI-Les Ateliers อีกครั้ง เหมือนว่าในช่วงเวลานั้นที่สร้างสรรค์ไปทำงานอยู่ที่ฝรั่งเศสอย่างเต็มตัว ความเชื่อมโยงกับเชียงใหม่จะค่อยๆ ถอยห่างออกไปเรื่อยๆ อย่างไรก็ตาม เขาก็หาทางทำงานที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเชียงใหม่จนได้ จากการไปร่วมงานกับ Prempracha’s Collection ผู้ผลิตและส่งออกสินค้าเซรามิกรายใหญ่ของเชียงใหม่ที่ไปออกงานแฟร์ที่นั่นพอดิบพอดี

A ceramic collection which is the result of a collaboration between Na Soontorn and the Prempracha’s Collection

“ผมเข้าไปช่วยเป็น art director ให้กับหลายๆ คอลเล็คชั่นที่จะมางานแฟร์ที่ฝรั่งเศส ดูแลตั้งแต่ดีไซน์ของตัวผลิตภัณฑ์ การโปรโมท งานกราฟิกที่จะถูกเอาไปใช้ในส่วนต่างๆ” นอกจาก Prempracha’s Collection สร้างสรรค์ยังร่วมงานกับแบรนด์อย่าง DEESAWAT และ Bambunique ด้วย โดยหลังจากเป็นที่ปรึกษาของแบรนด์อื่นๆ ได้กว่า 5 ปี สร้างสรรค์ก็ก่อตั้ง JAOBAN ขึ้นมาในโอกาสที่เขาถูกเลือกเป็นหนึ่งในดีไซเนอร์ไทยให้ไปโชว์ผลงานในบูธของ SACICT ในงาน MAISON&OBJET “คุณสุวรรณ คงขุนเทียน คิวเรเตอร์ในปีนั้นเขาคงเห็นเราเป็นที่ปรึกษามาพักหนึ่งแล้ว เลยชวนเราไปร่วมครั้งนั้นด้วย ซึ่งข้อแม้ก็คือเราต้องเปิดบริษัทขึ้นมาเป็นเรื่องเป็นราว”

ในเวลา 3 ปีที่ผ่านมา JAOBAN เปิดตัวโปรดักต์ออกมาเป็นจำนวนไม่มากนัก ที่คุ้นๆ ตากันอยู่คงจะเป็นกระจก NIAN (เนียน) และที่แขวนเสื้อ KONG (ก๊อง) หรือล่าสุดอย่างโคมไฟตั้งพื้น ซึ่งทั้งสามชิ้นที่กล่าวถึงนี้เกิดขึ้นจากหลักการทำงานเดียวกัน “กับ NIAN นั้น รวมๆ แล้วคือเราต้องการ push ช่างฝีมือของเราเอง คอนเซ็ปต์คือผมไปจ้างช่างตัดกระจกในเชียงใหม่ให้ตัดกระจกที่ไม่เป็นวงกลมหรือสี่เหลี่ยมซึ่งเป็นรูปทรงที่เครื่องตัดกระจกทำได้ เพื่อจะบอกกับเขาว่าอย่าเอาคำว่า ‘handmade’ มาเป็นข้อแก้ตัวที่งานออกมาไม่เนี้ยบ” ในส่วนของตัวกรอบไม้ไผ่ สร้างสรรค์เลือกทำงานกับช่างฝีมือที่ทำงานอยู่ในโรงงานที่บ้านเพื่อทดลองว่าถ้าหากไม่จ้าง outsource จะสามารถทำงานได้หรือไม่ เช่นเดียวกันกับโปรเจ็คต์โคมไฟตั้งพื้นไม้กลึง ที่เขาลงไปทำงานร่วมกับหมู่บ้านตองกายที่มีประวัติศาสตร์การทำไม้กลึงมาอย่างยาวนาน แต่ในปัจจุบันจำนวนช่างฝีมือ (สล่า) ในหมู่บ้านกลับลดลงเรื่อยๆ

“เรามองงานคราฟต์เป็นมากกว่า consuming product แต่มันเป็นผลผลิตจากท้องถิ่น เหตุผลดั้งเดิมของคราฟต์คือการทำได้เอง ใช้วัสดุท้องถิ่น เป็นเหมือนของยังชีพหรือองค์ความรู้ที่สืบทอดกันมา” หลักการทำงานที่ว่าของสร้างสรรค์อาจเรียกได้ว่าเป็นการทดลองทำงานคราฟต์ในเชิงทฤษฎี ที่เน้นไปที่การทำงานโดยรักษาแนวคิดดั้งเดิมของงานฝีมือเอาไว้นั่นคือการไม่เปลี่ยนไปผลิตสินค้าในโรงงาน จากมุมมองนี้ ต้นทุนการผลิต พลังการผลิต และมาตรฐานการผลิต จึงกลายมาเป็นกำแพงเมื่อ JAOBAN ต้องส่งออกไปยังเวทีโลก สร้างสรรค์เล่าว่ามี buyer ติดต่อมาทันทีในครั้งแรกที่ JAOBAN ไปออกงานแฟร์ และก็เป็นไปตามคาดเมื่อ buyer ถามหาการรับรองมาตรฐานวัสดุ (ISO) ซึ่งเป็นไปไม่ได้ที่แบรนด์ท้องถิ่นจริงๆ จะมีทุนพอที่จะไปขอเครื่องหมายรับรองประเภทนั้น อีกอย่างที่เขาเจอมากับตัวคือ กำแพงภาษีของสหภาพยุโรป ที่ทำให้สินค้านำเข้าจากทวีปอื่นๆ สู้ราคากับสินค้าท้องถิ่นไม่ได้

NIAN, 2016 (NIAN is the Thai word used to describe something smooth and delicate)

“จำนวนของออเดอร์ก็เป็นปัญหา มันเป็นไปได้ยากมากที่เราจะทำงานแบบที่มันคราฟต์จริงๆ ในปริมาณที่เขาเรียกร้อง” สร้างสรรค์บอกกับเราว่าสิ่งเดียวที่ JAOBAN สอบผ่านคือดีไซน์ที่พอจะตรงกับรสนิยมฝรั่งแต่ก็ยังสามารถรักษาอัตลักษณ์ความเป็นท้องถิ่นไว้ได้ไม่ขาด อย่างที่กล่าวไปแล้วในช่วงต้นว่า JAOBAN เป็นแบรนด์เชิง experimental กรณีการทดลองตลาดโลกของ JAOBAN ทำให้เห็นความย้อนแย้งของการผลิตงานฝีมือในปัจจุบันไม่น้อย โดยเฉพาะคำถามว่ามันสมเหตุสมผลหรือไม่ ที่จะส่งออกงานออกแบบของไทยไปยังตลาดต่างชาติ “มันไม่สมเหตุสมผลตั้งแต่เราเอาของที่ local มากๆ ไปส่งออกแล้ว เพราะมันจะสูญเสียความเชื่อมโยงกับท้องถิ่นไป ไม่ใช่แค่ในกรณีของการส่งออกอย่างเดียว การขายในประเทศก็เหมือนกันที่เปลี่ยนให้มันกลายเป็นสินค้าของชนชั้นกลางและทำให้ความท้องถิ่นกลายเป็นแค่เปลือก” สร้างสรรค์ยังกล่าวต่อถึงบทบาทของ TCDC Chiang Mai ว่า มีพันธกิจสองอย่างที่ขัดขากันเองอยู่คือ creative + business TCDC Chiang Mai เลือกงานฝีมือที่มีอยู่ในท้องถิ่นเป็นหมุดตั้งต้นในการทำงาน ซึ่งก็เป็นเรื่องดีที่ TCDC พยายามเอาดีไซน์เข้าไปในพื้นที่และพยายามสร้างเวทีให้คนเหล่านั้นอย่างไรก็ตาม สิ่งที่ควรระวังก็คือถ้าผลักดันทางธุรกิจมากเกินไปงานฝีมือจะกลายเป็นแค่ “ของฝาก” ที่นักท่องเที่ยวซื้อกลับไปเป็นของที่ระลึก โดยเฉพาะในเมืองท่องเที่ยวอย่างเชียงใหม่

“ตอนนี้ทุกคนกลายมาเป็นพ่อค้าขายของฝากนักท่องเที่ยวกันหมด ถ้าไม่ร่วมกันคิดตอนนี้มันจะมีปัญหา เพราะเชียงใหม่ยังไม่มีทิศทางที่ชัดเจน” สร้างสรรค์มองว่าตอนนี้เชียงใหม่ยังหาจุดยืนหรือตำแหน่งแห่งที่ของตัวเองไม่เจอ การไม่มีฐานการผลิตเป็นโรงงานแบบกรุงเทพฯ ทำให้สินค้าที่นี่แข่งขันด้านราคาไม่ได้ ส่วนถ้าจะไปสู่เรื่องความเนี้ยบของผลงาน ปัจจุบันต้องยอมรับว่างานฝีมือเชียงใหม่นั้นได้มาตรฐานในระดับหนึ่ง แต่ก็ไม่ได้เนี้ยบขนาดที่จะทำให้สินค้ามีมูลค่ามากเท่างานฝีมือจากประเทศญี่ปุ่น ที่ผ่านๆ มาการสนับสนุนจากภาครัฐที่ต้องการสร้างสิ่งที่เรียกว่า “เศรษฐกิจสร้างสรรค์” ทำให้เกิดทั้งผลดีและผลเสีย แน่นอนว่ามีคนกลุ่มหนึ่งได้รับผลดีจากการสนับสนุนนี้แน่ๆ แต่ขณะเดียวกันการมุ่งไปข้างหน้าแบบที่ยังไม่มีทิศทางที่แน่นอนก็อันตรายพอกัน คงต้องรอดูต่อไปในอนาคตว่าทิศทางที่ดีและที่ควรจะเป็นของงานฝีมือในเชียงใหม่นั้นจะเป็นอย่างไร

Wooden furniture, a collaboration project with DEESAWAT

JAOBAN is a brand of craft furniture first established in 2016 by Sarngsan Na Soontorn, a Chiang Mai based designer who is now living and working in France. “I’m the only person behind the brand. JAOBAN is a project I initiated to test the feedback for Chiang Mai’s crafts in the global market. With my parents now getting older, I will have to go back and take care of the family business soon.” His family began their craft business back when his father was a teacher in Chiang Rai, prior to later moving to Chiang Mai where he started selling craft products. He gained experience in wood carving before starting a full-on, family-run woodcarving business.

“Craft has always been there with me as a part of my childhood. When I was studying architecture Chiang Mai University, I learned to appreciate the notion and value of vernacular creations from Chunlaporn Nuntapanich quite a great deal.” Despite being an architecture graduate, Na Soontorn’s goal has never been becoming a professional architect. The profession he had in mind for himself was to become an environmental activist (presumably due to influence from Nuntapanich, who is an avid environmental activist), but such intention wasn’t pursued for he realized the unpleasant fact that dealing with something that involves a city at such a large scale meant that he would have to get involved in the legal business and politics. “When I first came to France, the intention to deviate my career path from architecture was followed by a decision to study industrial design. I wanted to try working with something at a smaller scale, not large built structures that required such a long time for one’s ideas to be materialized and completed. With the scale of industrial design creations, I get to have complete control over both the thought process and production.”

A ceramic collection which is the result of a collaboration between Na Soontorn and the Prempracha’s Collection

Na Soontorn spent three years studying industrial design at ENSCI-Les Ateliers. After graduation, he worked as a designer for Paris-based studios such as Gabriele Pezzini, Constance Guisset Studio and Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec before he was offered a special lecturer position at ENSCI-Les Ateliers. The life as a full-time Paris resident made the distance between him and Chiang Mai seem even farther. Nevertheless, he managed to find a way to work on a project that could reconnect him to Chiang Mai once again through collaboration with Prempracha’s Collection, a major manufacturer and exporter of ceramic products based in Chiang Mai who happened to be in Paris for a trade fair.

“I was working as the art director for their collection that would be shown at the trade fair in France, overseeing the design, promotion and graphic design that would be used in the event.” In addition to Prempracha’s Collection,

Bamboobox, a collaboration project with Bambunique developed in 2015

Na Soontorn has worked with brands such as DEESAWAT and Bambunique and, after over five years as a consultant for many reputable brands, he founded JAOBAN. It was also the time when he was selected as one of the Thai designers who would be featuring works at SACICT’s booth at MAISON&OBJET. “Suwan Kongkhuntian, who was the curator of that year, probably saw me working as a brand consultant for quite a while. He asked if I wanted to be a part of it with the only condition being that I had to open a legitimate company.”

Over the past three years, JAOBAN has launched a fairly small number of products. Some of the most well-known works are the ‘NIAN’ mirror and the coat rack ‘KONG,’ as well as a floor lamp which is the most recent work of the brand. All three works were conceived under the same work philosophy. “With NIAN, I essentially wanted to push the limits of the artisans who were working for me. The concept is actually derived from the experience of finding a craftsman who would cut a piece of a mirror into other shapes than that of a standard rectangle or circle, shapes that cannot be cut using a machine. I wanted to show them that one shouldn’t use the word ‘handmade’ as an excuse for the unrefined details of one’s work.” The bamboo frame is the result of Na Soontorn’s collaboration with an artisan who works in the factory of his family’s woodcarving business. He experimented with the production process that didn’t rely on any outsourcing just to see if the whole operation could be carried out. The same approach was taken with the floor lamp where he worked closely with the local community called Ban Tong Kai whose villagers possess a long history and know-how in terms of wood lathing. Unfortunately, the number of local artisans (Sala) who are masters of these skills is gradually dwindling.

“I look at crafts as something that is more than just a consumer product but a local product. The primary reason behind a craftwork is that it is self-made and uses locally available materials. It is a survival tool, the product of ancient know-how that has been passed on through generations.” His method is considered to be quite experimental in theory, which puts emphasis on the conservation of the traditional concept of crafts and the refusal to industrialize the production process. For this particular aspect, the production costs, capabilities, and standards became an obstruction when JAOBAN was exported to the global market. Na Soontorn recalled gaining the immediate interest of, and contact from, buyers following their first trade fair. And as expected, when a buyer asked for the materials’ ISO, which is practically financially unattainable for a brand as local as JAOBAN, another dilemma became the European Union’s trade barriers that prevent imported products from winning the price war against local products.

KONG, 2016 (KONG means hang in Thai language)

“The number of the orders is also a problem. It’s almost impossible for us to create true craft products in the volume that they are asking for.” Na Soontorn said that the only test that JAOBAN was able to pass was the design, which matched the tastes of the Western clientele while the products’ local identity was kept intact. As mentioned earlier, JAOBAN is an experimental brand and a testing of its products in the international market allows for one to see the conflict in Thailand’s craft industry, especially the rationality of exporting Thai craft products. “Exporting products that are very local doesn’t make any sense from the start because the connection with the locality is lost. And it isn’t just the case of exporting, but the domestic market has turned crafts into consumer products for the middle class, consequentially turning its local identity into something so superficial,” described Na Soontorn of the role of TCDC Chiang Mai and its seemingly conflicting missions of ‘creative+business.’ With TCDC Chiang Mai choosing locally made products to serve as the starting point of its operations, it is a good thing that TCDC is trying to introduce design into these local communities and create a platform for these people. Nevertheless, TCDC has to be very careful and not push everything too hard to the point where these craftworks end up being just ‘souvenirs’ for tourists, especially in the context of a tourism city such as Chiang Mai.

“Everyone is turning into souvenir makers and sellers. If we don’t think about it now, it’s going to be problematic because Chiang Mai doesn’t have a definite direction of where it is going to go,” described Na Soontorn who views Chiang Mai as having still not found its ground or where it is going to stand. Unlike Bangkok, Chiang Mai doesn’t have its own production base, causing its products to demand a less competitive price. As for the issue of the works’ details, the standards of Chiang Mai crafts are quite good but they are still not at the same level as that of Japan’s. The government’s attempt to push forward this so-called ‘creative economy’ has rendered both positive and negative effects. Surely, there is going to be a group of people who will benefit from this support but moving forward without knowing the definite direction is also dangerous. What will and should the direction and future of Chiang Mai crafts be? All remains to be seen.