A VARIETY OF WORKS, A VARIETY OF STORIES, TOLD IN THE UNIQUE ARTISTIC LANGUAGE OF EACH NEW GENERATION OF ARTISTS IN EARLY YEARS PROJECT #8

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Now in its eighth year, the Early Years Project (EYP#8) brings together eight emerging artists selected to participate in a mentorship and development program culminating in a group exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC). The show presents a diverse array of practices—ranging from sculpture, drawing, and painting to textiles, ceramics and installations. While mixed media features prominently, it is notable that, proportionally, video works appear less frequently in EYP#8 compared to The Shattered Worlds: Micro Narratives from the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the Great Steppe, an exhibition by more established artists currently on view one floor above. Thematically, EYP#8 is just as wide-ranging, with each artist offering distinct narratives, bringing their own emotional temperature to the work.

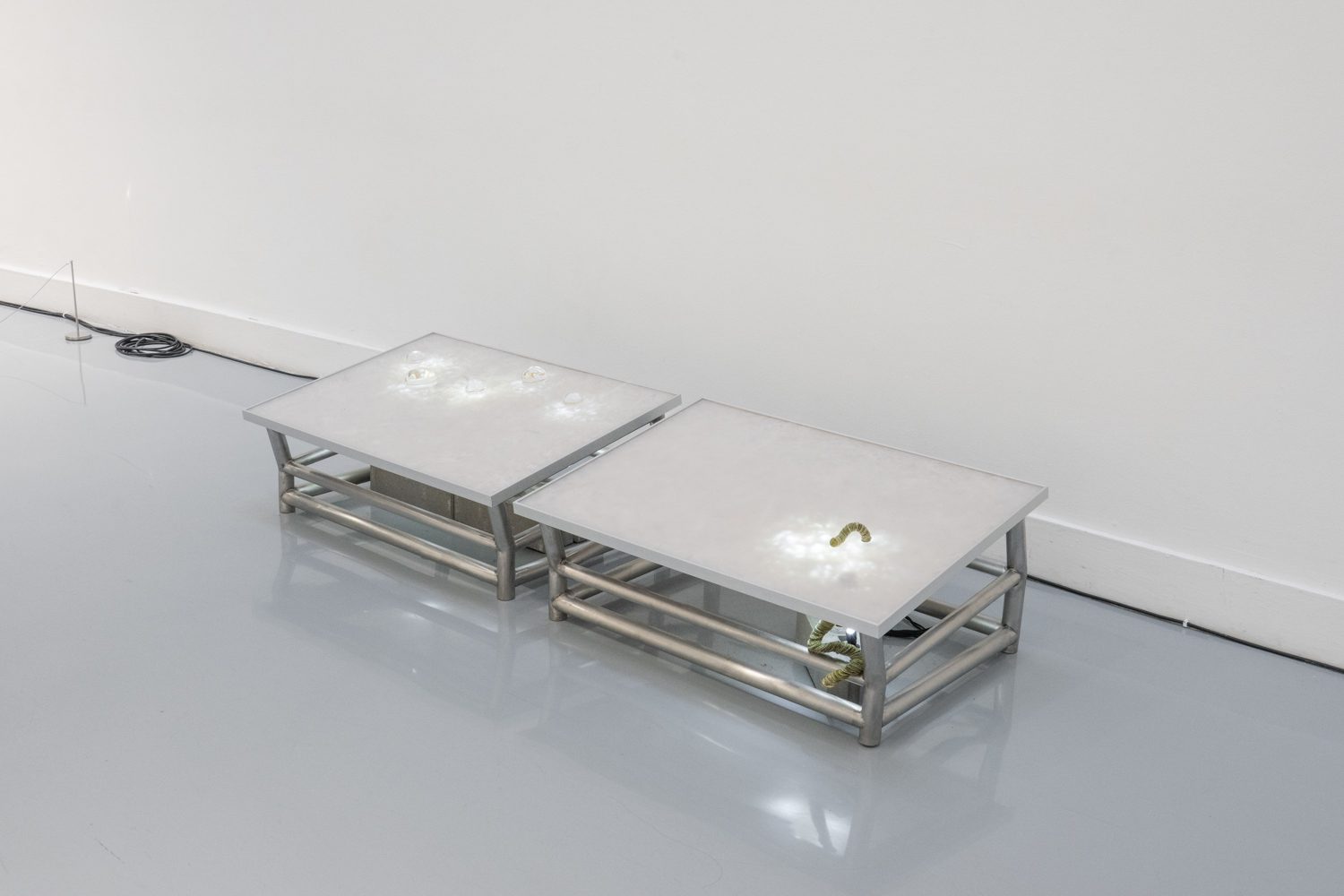

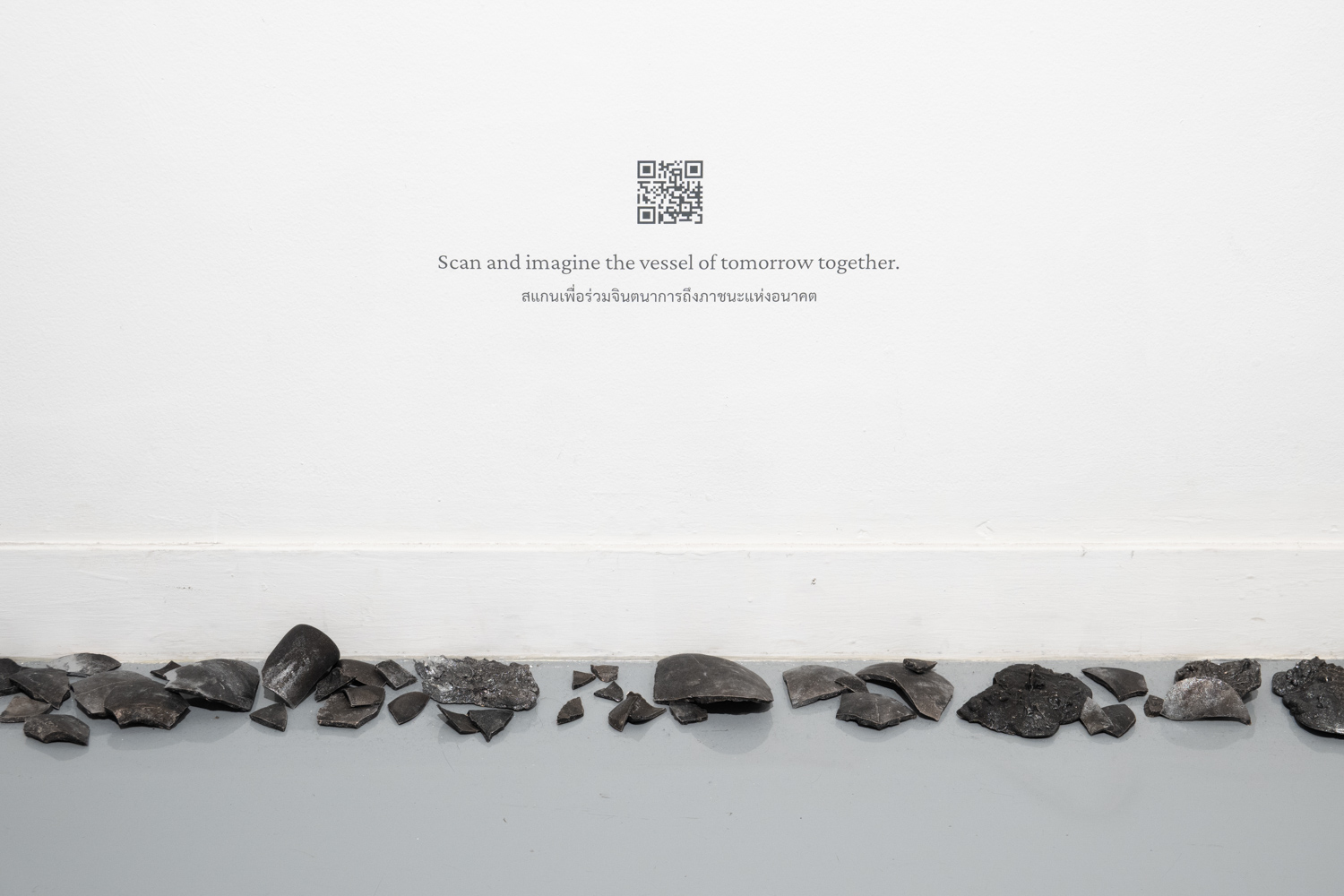

If we’re talking about playful tones, Vessel (2025) by Papimol Lotrakul might just be the most imaginative and delightfully eccentric work in the show. Her fascination with ‘vessels’ stems from their role as essential, everyday tools; objects that have existed across civilizations and quietly borne the weight of human history. But beyond their utility, vessels carry layered symbolic meanings across cultures. For Papimol, they speak to a deeper yearning: the human desire to fill a sense of emotional voids. In this series, she presents six vessels, each with a distinct shape, personality, and set of quirks (one even vibrates). Each is paired with a speculative, dystopian narrative drawn from her imagination. One story envisions a world overtaken by aliens, where humans become memory-less laborers. Another imagines endless acid rain, a world devoid of art and music, where people reject childbearing, forcing authorities to engineer synthetic ways to replenish the population. In yet another, dreams are recorded and sold as commodified data. While these scenarios are wildly entertaining and often cinematic, they tap into deeper questions. Beneath the playfulness lies a sincere curiosity about the future of humanity, told from the perspective of an artist who, like many of her generation, will be a part of whatever future unfolds.

Yotsunthon Ruttapradid is among the artists in EYP#8 who questions the effects of digital communication especially, how we think and behave as a society. His work Hyperlink Inter Me (2025), a non-narrative video sculpture, takes the form of a curved archway composed of multiple television screens. Each screen displays a stream of letters, numbers, and fragmented visuals without a cohesive storyline. The result is an ongoing cascade of content that recalls today’s social media feeds, where meaning is often secondary to short-term emotional stimulation. As viewers walk beneath the arch, the installation evokes the sensation of passing through an MRI scanner. Yet rather than revealing one’s internal organs, Yotsunthon’s tunnel enacts an algorithmic scan of the self, shaped by patterns of digital consumption. It compiles and translates behaviors and preferences into data, which ultimately transforms becomes identity into commodified, marketable information.

Positioned near Yotsunthon’s installation, Unexpected Growth (2025) by Apisara Hophaisarn offers a quiet counterpoint to the synthetic atmosphere of the digital world. Her work draws viewers into a space of restraint and simplicity, composed of small-scale installations built from stacked bricks. In some, delicate weeds sprout through the gaps; in others, grey-covered books rest seamlessly among the structures. A second component of the work features sheets of handmade paper crafted from those very weeds. Displayed in acrylic frames and set atop a truss structure, each sheet bears organic forms reminiscent of enlarged plant cells or microscopic life. The work originates from Apisara’s close observation of the urban environment, particularly the small, persistent weeds that push through the cracks of brick-paved sidewalks. She sees in their humble, often overlooked presence a quiet struggle for survival within the city’s arid, unyielding landscape. By transforming these weeds into paper, she initiated a reflective process, one that deepens her awareness of the interconnections between people, nature and in the world around her.

In this edition of EYP#8, several artists turn their focus toward social issues rooted in their hometowns. Among them is Nitithorn Nooklin from Surat Thani, who addresses the environmental crisis affecting the sea through NEW species (2025), a series of sculptures that are as charming as they are unsettling. The figures, crouched and hunched, with their bodies covered in coral and shells that sprout like tumors, appear tethered to the rocky outcrops beneath them. Accompanying the sculptures is Kammapanthu (2025), an animated film about the underwater life. Lalita Singkhampuk, drawing from her family’s experience in Mae Sai, Chiang Rai, presents two mixed-media installations, Till We Meet Again (2025) and Goodbye For Now (2025). The works document the practice of house-raising, a strategy her family adopted in response to recurring floods, particularly following the devastating flood of 2024.

At first glance, raising a house may seem like a practical decision made by a single household bracing for future flash floods. But when viewed in the context of Lalita’s installation, which features small wooden supports propping up a tilted section of flooring, it becomes a quiet expression of resistance. Her work reflects the broader struggle of local communities striving to remain in place amid increasingly severe natural disasters. It also points to a deeper structural issue, one exacerbated by the actions of powerful corporate interests. For families without the means to relocate or rebuild a new home, lifting the existing structure becomes the only viable option. Though it demands less financial investment, it carries significant risks, particularly regarding safety.

The Elephant Cosmology: Fossils and Civilizations (2025) by Thanawat Numcharoen is another work in which the artist turns to his place of origin for inspiration, this time through the enduring figure of the elephant. In Southeast Asian Buddhist-Hindu cosmology, elephants appear across a range of mythological narratives, including the belief that the world is a flat, expansive earth balanced on the backs of four elephants. Thanawat also references the founding legend of Sisaket, his hometown, where a royal white elephant, regarded as a symbol of merit and divine authority in the Ayutthaya kingdom, was said to have strayed into the region and was eventually captured by local mahouts. Alongside these myths, Thanawat incorporates historical realities into the work as well. Elephants were not only revered but also instrumental in shaping the physical and economic foundations of ancient kingdoms, serving as laborers in construction and carriers of trade goods.

Whether drawn from legend or fact, the elephant has long been central to the consolidation of kingdoms and the projection of royal power. Thanawat explores these layered meanings through a series of drawings, acrylic paintings on canvas, sculptures, and prints, displayed in a manner reminiscent of historical museum exhibitions. His references to Buddhist-Hindu cosmology speaks not only to the past, but to its lingering influence in the present. Though elephants today are largely removed from political and economic life with many now relegated to the tourism industry, certain belief systems surrounding them, once established and passed down through generations, continue to shape aspects of legitimacy within contemporary society.

In addition to visual artworks, this year’s edition of EYP also includes performance art. Things Left to Forget (2025) by Pitchapa Wangprasertkul is a deeply personal work that incorporates a collection of everyday objects, from pillows, nails, coat hangers to a steering wheel, recreated using delicate, pastel-toned fabrics, lace, and crochet. Each object is tied to the artist’s experience with domestic abuse, which left lasting effects on both her body and mind for years afterward. A key element of the performance is an oversized pillow, its exaggerated scale intended to communicate the magnitude of the harm, greater than what anyone in her family, or perhaps even the artist herself, could have fully understood at the time. The soft, gentle materials enveloping each object act as a form of protection, as if neutralizing their capacity to inflict further harm.

Pipatpong Seepeng also draws from personal history, exploring internalized emotions and familial experiences in Persona (2024–2025). The work is presented within a small, enclosed room constructed inside the gallery. Upon entering, one feels as though they’ve stepped into the artist’s subconscious. The installation brings together textiles, papier-mâché dolls, mural paintings, drawings, unused objects, and sound—all seamlessly integrated into a cohesive, immersive environment. Through this layered space, Pipatpong addresses the pressure to conform to familial and societal expectations, which led him to suppress parts of his identity, including his gender expression.

What stands out most in Persona is the unsettling atmosphere Pipatpong creates within the room itself. It’s an intensity heightened by his use of textiles, a medium rarely encountered in such raw and expressive form. The entire installation feels like a canvas violently splashed with paint, with little regard for control or consequence. And yet, despite the difficulty of articulating exactly what the work is, many who encounter it may find something unexpectedly familiar: a glimpse of their own buried emotions reflected in his.

Early Years Project #8: Be Your Own Island is now showing through 29 June 2025 at the Main Exhibition Hall, 7th floor, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC).