FROM EXPLORING THE LANDSCAPE OF CONFLICT, THE EXHIBITION ‘UNDO PLANET PART 2: LAND ART AND NON-HUMAN BEINGS’ EXPANDED TO ADDRESS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND NATURE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE ANTHROPOCENE ERA

TEXT: KANDECH DEELEE

PHOTO COURTESY OF BANGKOK ART AND CULTURE CENTRE (BACC) EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

While ‘Undo Planet Part 1: Undo DMZ‘ examined the complexity of relationships forged within a specific terrain, including a forest co-produced through inter-state conflict, the remnants of war whose original forms have been obscured, and the resurfacing of the primordial once human activity is withdrawn, ‘Undo Planet Part 2: Land Art and Non-Human Beings’ shifts its focus outward toward the dispersed and entangled relationships between humans and nature across the globe. It brings viewers face to face with what is familiar, intimate, and ordinary, so commonplace that we often forget how these interactions began as the simplest of gestures: not through domination, but through an attempt to connect.

The sun, flowing water, the earth, and the sky surround us with both closeness and mystery. Though ever-present and shared with humanity since deep time, the essence of nature is never easily grasped. Nature continues to release forces that are both benevolent and destructive, consistently exceeding human expectations. To survive the manifold challenges of this pale blue dot1, humans must learn to seek new modes of connection with the natural world.

The sunlight that passes through the four tunnel apertures of Sun Tunnels (1978) by Nancy Holt, aligned with the summer and winter solstices2, points to a process of human perception, learning, and adaptation grounded in interaction with the natural world. Humans observed that the Earth’s orbit around the sun follows recurring patterns, cyclical and systematic, giving rise to calendars capable of predicting weather conditions with greater precision. As a result, agriculture, animal husbandry, foraging, and hunting could be carried out more effectively, no longer reliant on blind chance or left solely to be sorted by the forces of natural selection.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Although scientific language often speaks in terms of ‘discovery,’ such as determining the specific dates on which the summer and winter solstices occur each year, Sun Tunnels, operating within the register of art, allows these calculations to be made visible. Apertures of varying sizes cut into the tunnel walls generate different images of sunlight across the seasons. Holt’s tunnels thus become a kind of calendar, one that turns our attention back to the calendar itself as an invention, something constructed rather than given. The calendar is not an intrinsic property of the universe. Rather, it is a method through which humans come to understand nature by producing a particular form of representation. It renders nature into an image that appears more stable, more fixed, and easier to comprehend, even though the temporal measurements it relies upon are, in reality, always subject to slight and continual deviation.

Humans, then, are not masters of time, nor do we command nature or perceive the true essence of all things with complete clarity. Each time we attempt to do so, what emerges is merely the construction of new instruments through which we compare ourselves to nature and seek connection with it. At the same time, we may imagine, within the limits of our own constraints, the possibility that other living beings negotiate and relate to nature through entirely different means. Bears know when to enter hibernation. Trees shed their leaves in winter to reduce transpiration. Seagulls migrate south each year to escape the cold of Siberia. None of these strategies can be dismissed as untrue, nor can we claim that our own way of knowing is the only authentic one.

If calculating and organizing the seasons through the calendar is merely one form of representation through which humans connect with nature, then it follows that other pathways and methods of connection must also be possible. Barruntaremos (Inklings) (2021) by Asunción Molinos Gordo explores Cabañuelas, a system of weather prediction passed down through generations in Spain, Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa. This method relies on observing recurring environmental changes until they form patterns capable of anticipating weather conditions that may follow. For example, when the north wind known as Cierzo arrives, temperatures are expected to drop rapidly. In August, lifting a stone to find moisture beneath it is read as a sign of heavy rainfall in the following April and May. When the moon rises upright, rain is believed to be imminent, while a tilted moon suggests dry weather ahead.

It is worth noting that this ancient mode of weather prediction is grounded in a logic of interdependence, one in which multiple elements act upon one another to yield a forecast of what may come. Wind, direction, stone, water, and the moon are all intricately entangled. Cabañuelas does not seek to uncover every mechanism orchestrating nature behind the scenes. Rather, it operates through careful observation, tracing certain lines of possibility that emerge from an endlessly interconnected web of relations. When something shifts out of place, these lines of probability are correspondingly bent and altered. No single method of prediction can ever account for all the variables at work within such fields of possibility. Some forces may contribute as ‘actors’ yet remain largely imperceptible. At moments when one such actor changes, the ‘familiar’ trajectories of possibility can abruptly fracture.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

As recounted by Pedro Sanz Moreno, a shepherd interviewed in Barruntaremos (Inklings), everything has changed as a result of shifting human behavior. The proliferation of cars and airplanes, he explains, has caused the climate to change more rapidly and become increasingly volatile, producing what he describes as ‘an interference in the signals of the landscape.’ He recalls the arrival of Storm Filomena, when he was able to predict that snow would fall, yet could not have anticipated the sheer magnitude of the snowfall that followed.

Moreno’s account points to the onset of the Anthropocene, a moment in which human activity disrupts the Earth’s natural conditions with an intensity that exceeds the planet’s capacity to maintain equilibrium3. Representations that once mediated human connection with nature have become distorted, turning into evidence of broken signals and failed transmissions. The elements of probability have been interfered with and reshaped by forces that those involved cannot fully comprehend or control. Ultimately, these disruptions place human existence itself at risk.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

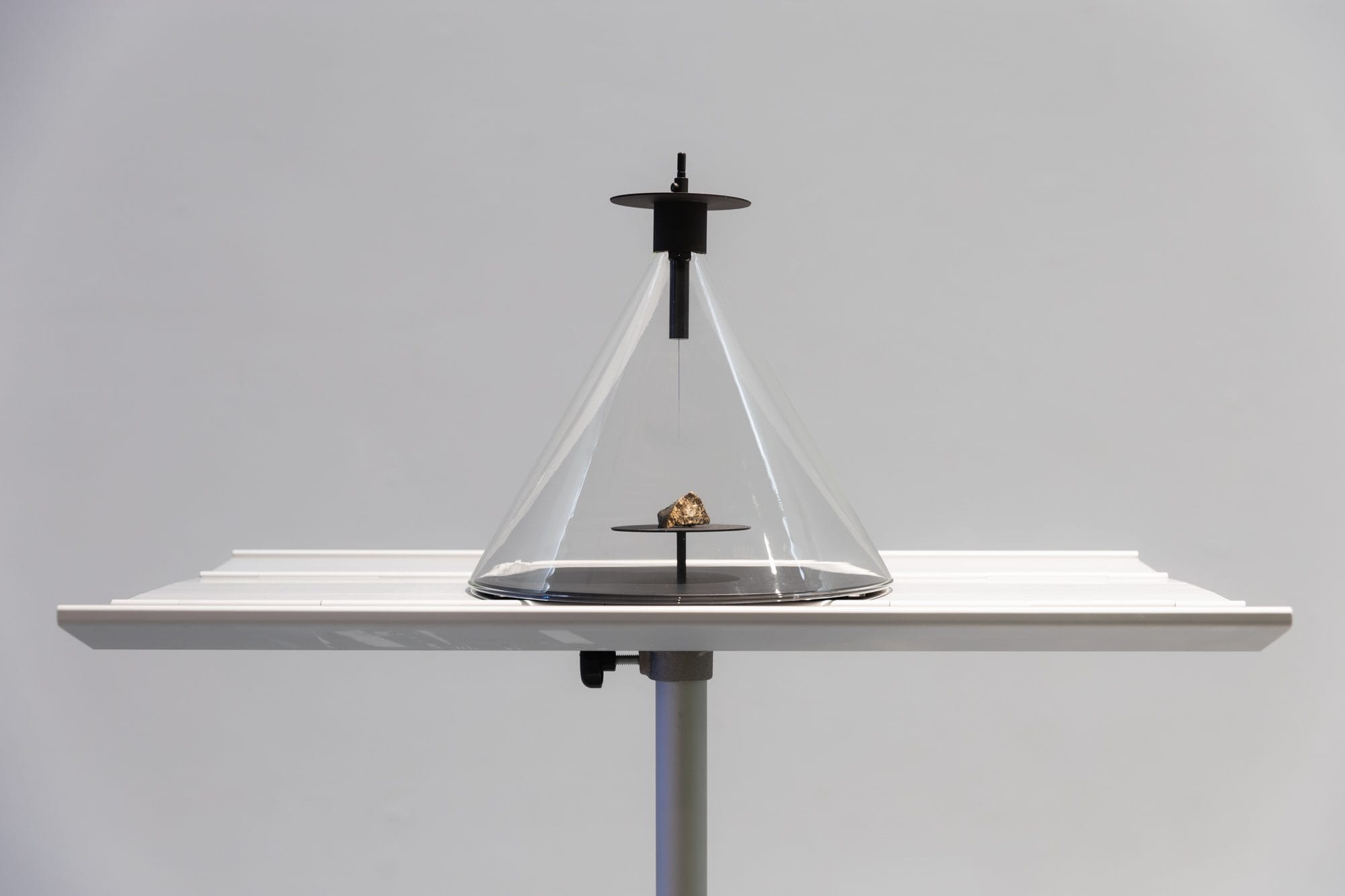

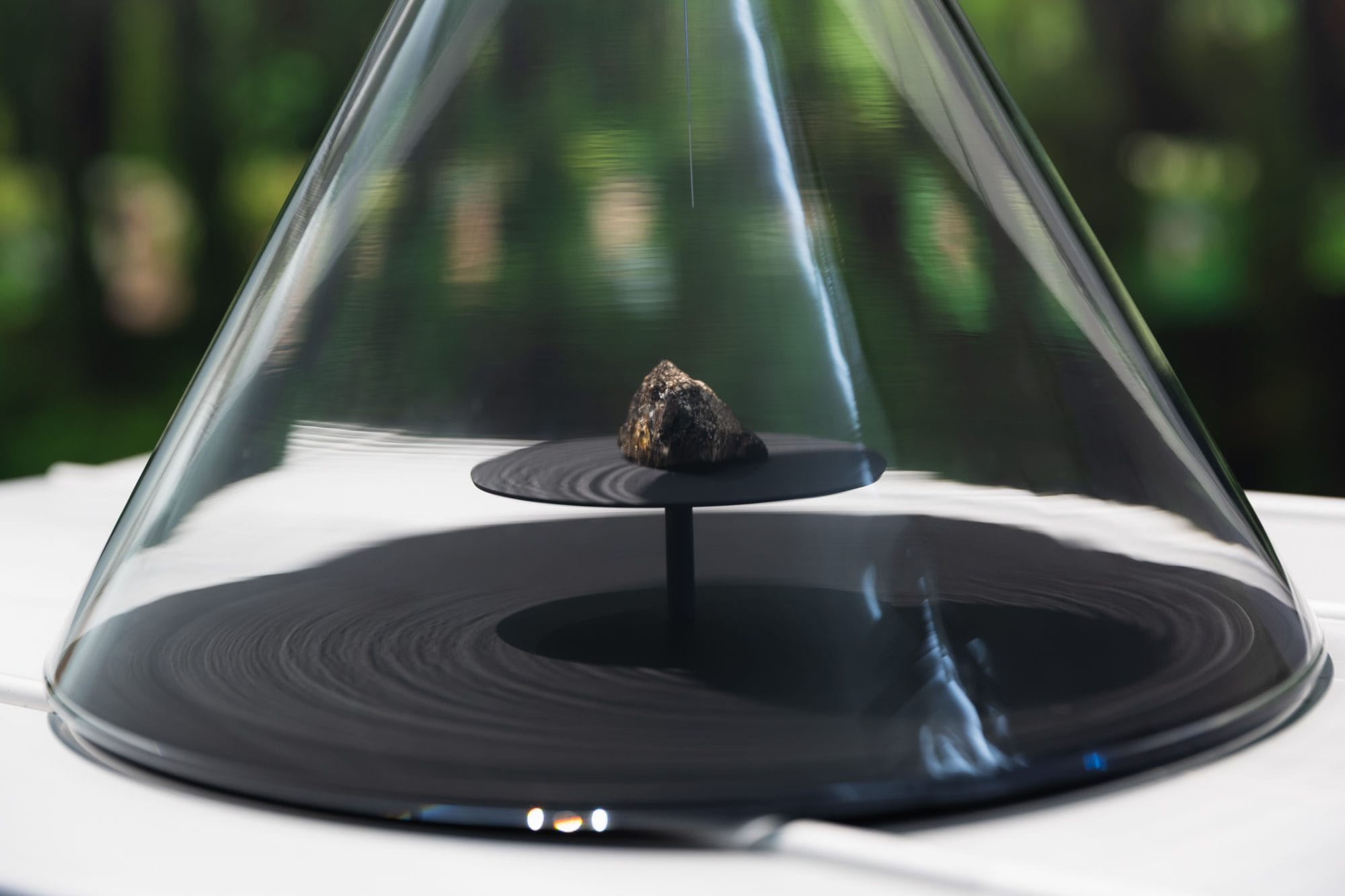

Human activity that distorts our interactions with nature appears with particular force in Ambergris (Capture and Dispersal) (2024) by Dane Mitchell. In this work, the artist presents natural ambergris, a substance produced through the digestive system of sperm whales, installed alongside a distillation apparatus that releases its scent as vapor. This is paired with a diffusion device emitting a synthetic ambergris fragrance, produced through the microbial fermentation of carbohydrates.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

In one sense, this could be seen as a human achievement, the ability to replicate a natural substance and transform it into something of our own making. Even so, natural ambergris continues to carry greater value, distinct qualities, and desirability within the perfume industry than its synthetic counterpart. The distance between the two is therefore measured by criteria of purity and naturalness. Yet environmental crises driven by human activity, intensifying year after year, have begun to interfere with the very conditions under which natural ambergris forms. As the work’s description notes, ‘sperm whales have become living repositories of industrial pollution.’ Ambergris produced through their digestive systems can no longer avoid contamination by industrial pollutants. In this light, the work calls into question the very distance between polluted natural ambergris and synthetic ambergris.

The two motors installed to release vapor thus evoke the image of factories and industrial systems that absorb and extend themselves outward, generating repercussions across the surrounding ecology. When all things are interconnected, mutually dependent, and continually affecting one another, industrial pollution cannot operate in isolation from ecological and environmental systems. Its impacts, both perceptible and beyond perception, become channels through which industrial contaminants infiltrate the environment, transforming it into an endless site of pollution production. The sperm whale, in turn, is rendered a kind of machine that absorbs residues and produces ambergris contaminated with particulate traces of pollution.

The story of the sperm whale and contaminated ambergris reveals that humans have not merely ‘fallen out of sync’ with their original relations to nature. Rather, activities driven by late capitalism have intervened in, regulated, and exerted control over forces that were never fully controllable to begin with. Synthetic ambergris thus remains only an imperfect act of ‘replication,’ incapable of serving as a one-to-one substitute. More troubling still, the very ‘original’ from which this imitation was learned, encountered, and connected has been damaged to the point that it may never return. In the future, we may find ourselves inhabiting a world composed solely of models, synthetic substances, and representations.

“The earth’s history seems at times like a story recorded in a book,

each page of which is torn into small pieces.

Many of the pages and some of the pieces of each page are missing”.

- Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970.

Much like the opening line of Robert Smithson’s filmed documentation of Spiral Jetty (1970), quoted earlier, the history of the world as it unfolds through our relationship with nature appears torn, frayed, and increasingly incapable of being stitched back together. It resembles a book from which certain pages have gone missing. Worse still than the act of interpretation meant to compensate for these absences is a persistent impulse to ‘write into’ the gaps, to force meanings that align with our own desires. The problem, then, may not lie solely in distorted understanding or in the failure to reconnect and coexist with nature ‘as it should be,’ as Moreno reflects in Barruntaremos (Inklings). Rather, it lies in our inability to foresee what the consequences of our interventions might ultimately lead us toward.

‘Undo Planet Part 2: Land Art and Non-Human Beings’ is on view at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 7th floor, from 19 December 2025 to 22 February 2026.

_

1 Carl Sagan, (1994), Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, Random House.

2 Summer Solstice refers to the day with the longest period of daylight in the year, while the Winter Solstice marks the day with the longest night of the year.

1 See further discussion of the Anthropocene in Trongjai Hutangkura and Natthakrit Yodrat. (2021). Anthropocene. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre (PublicOrganization). https://www.sac.or.th/portal/th/article/detail/224