EXPLORING MYTH, CARNALITY, AND DECAY THROUGH MICHAEL SHAOWANASAI’S EXHIBITION ‘G’SEIN’

TEXT: KANDECH DEELEE

PHOTO: PREECHA PATTARA EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Michael Shaowanasai’s G’SEIN is billed as a gathering of works drawn from the artist’s lifelong ‘observations and curiosities.’1 While the exhibition’s title and curatorial note initially flirt with the retrospective mode, it is worth noting that the works are neither arranged chronologically nor grouped thematically into a neat overview of ‘life and work.’ Instead, the exhibition returns the question back at the phrase itself, pressing on what ‘throughout the span of being an artist’ actually means. Although the framing reads almost like a summation of a career in preparation for retirement, the title resists closure. Shaowanasai twists the final consonant, transforming เกษียณ (retirement) into เกษียร, a word borrowed from kaseera, meaning ‘milk,’ as if to refuse the inevitability of ‘retiring.’

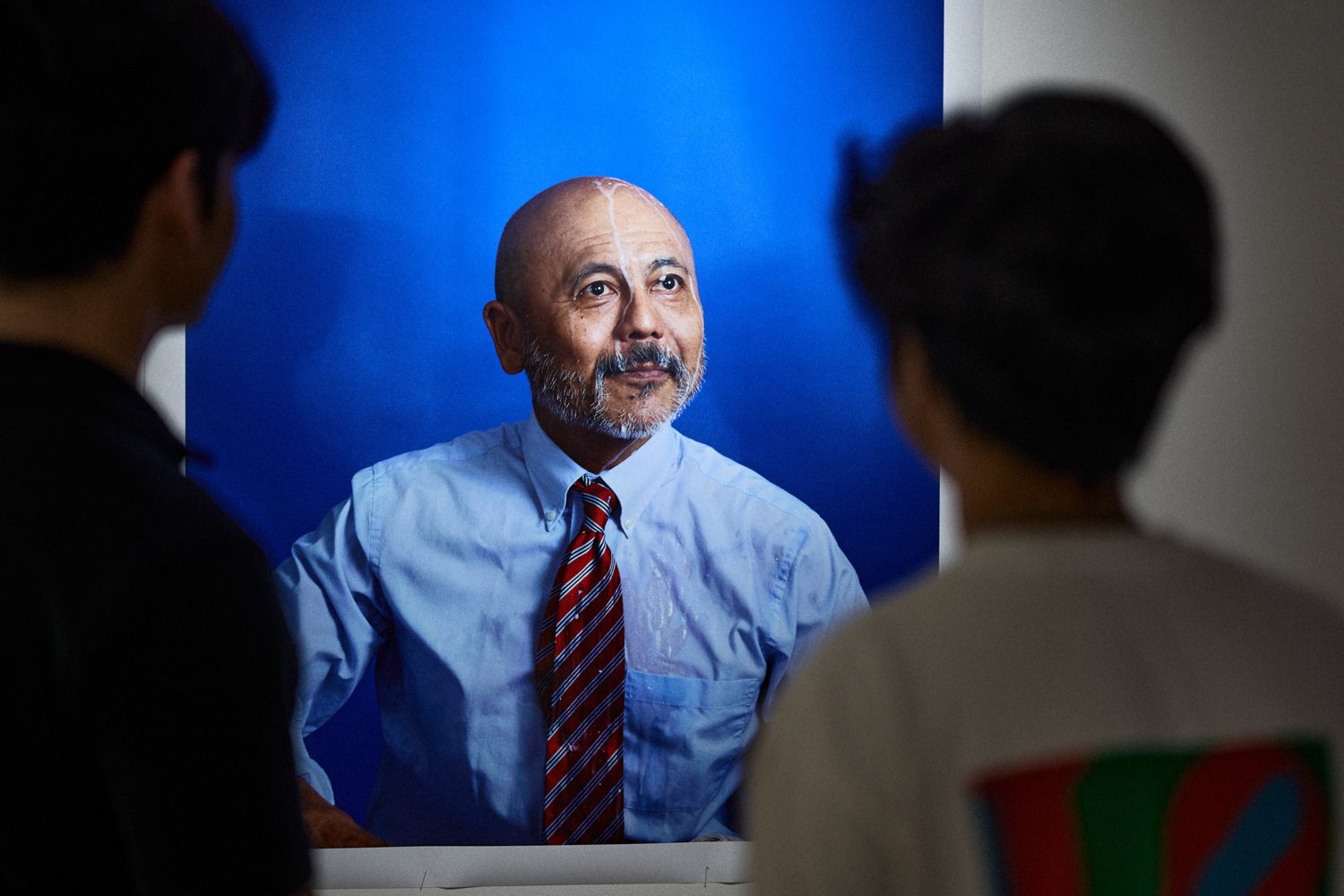

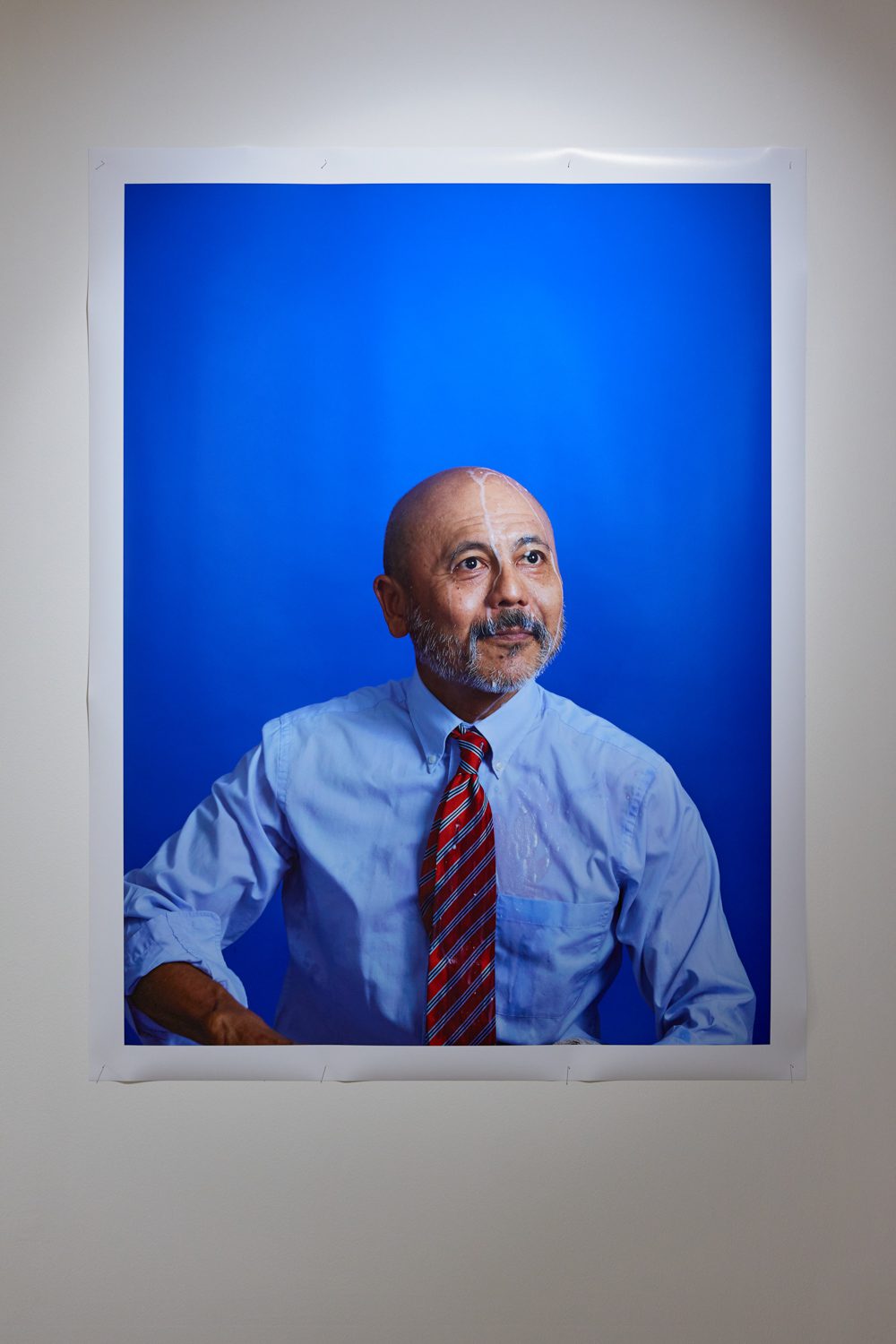

One of the most striking images from the exhibition is that of an older man, his wrinkles unconcealed, clad in a pale blue office shirt and a glossy red striped tie. His face is streaked with a milky fluid, sliding down to stain the fabric. His eyes tilt skyward, gleaming with a pleasure that makes the source of the substance unmistakable. The scene is neither mysterious nor coy. Viewers recognize it instantly: an office worker at the threshold of retirement caught in a bukkake scene. Here, G’SEIN overlays itself onto retirement through a play of sound, just as ‘milk’ and ‘semen’ overlap in form through their shared qualities as thick, opaque white fluids.

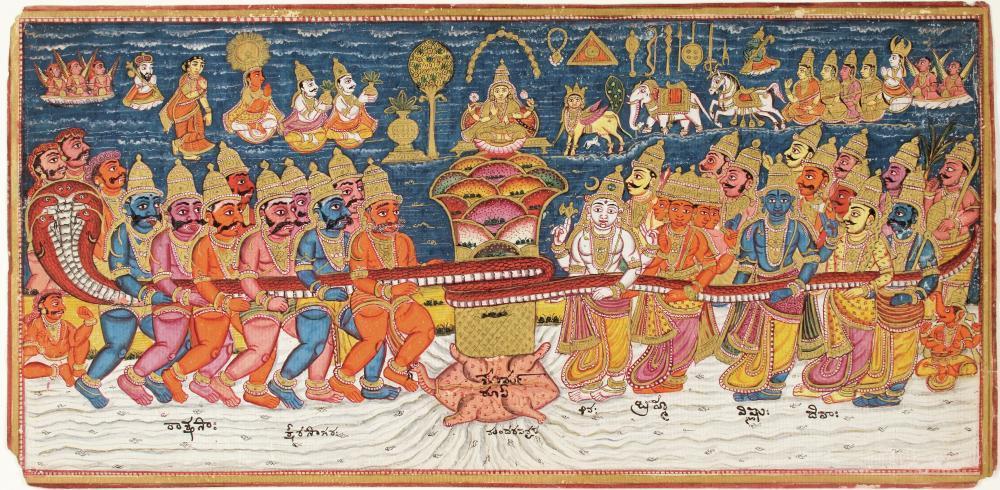

The Ancient Text of the Lord Creation (c.1825) Edwin Binney 3rd Collection. | Image courtesy of The San Diego Museum of Art. (https://saacsdma.org/collection/)

Parrott, R. (1983). A discussion of two metaphors in the ‘Churning of the oceans’ from the Mahābhārata. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 64(1/4), p. 19.

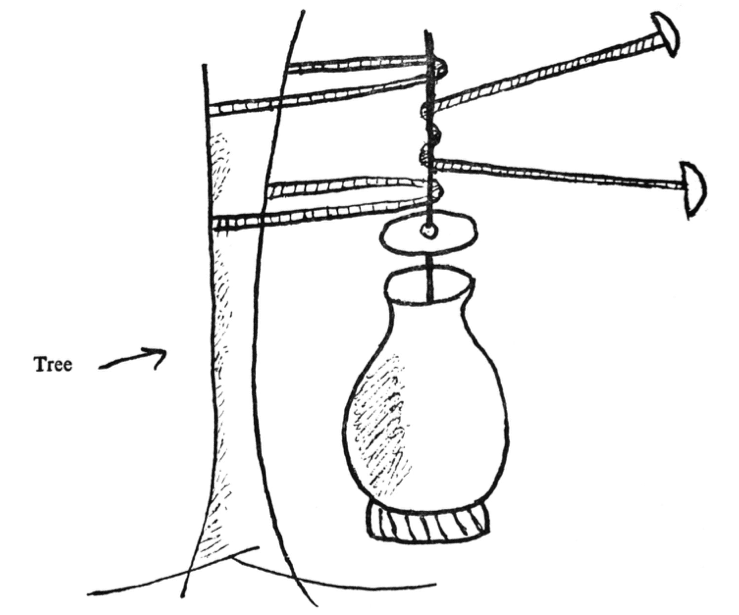

The choice of the word เกษียร is more than a cheeky pun or an act of slipping past propriety. The term resonates with the ancient cosmological tale of the ‘Churning of the Ocean of Milk’ (เกษียรสมุทร), a foundational Hindu myth in which gods and demons join forces to churn the cosmic sea of milk in search of ‘amrita,’ the nectar of immortality. To perform this feat, they heave Mount Mandara into the ocean as a churning rod, wrap it with the great serpent, Naga Vasuki, and pull in opposite directions until the sea is roiled into turbulence, giving up its hidden nectar.2 The image of cosmic churning echoes the very practical methods of ancient Indian dairy making, in which milk was agitated with a wooden staff and rope3 to produce butter or buttermilk. It’s an act of preservation, extending milk’s life just as amrita defies death. Yet the myth is not only about sustenance. The churning has long been linked to sexuality, fertility, and generative power. Mount Mandara becomes a phallic axis, whipped and tugged in rhythm, producing the ‘waters of life.’ The nectar of immortality that emerges at the end can be read, quite plainly, as semen, the life-giving fluid brought forth through ritual exertion.

Churning, grinding, tugging, rubbing: each becomes an act thick with expectation, a kind of karma, labor traded for time and exertion in the hope of eventual fulfillment; of consummation. The metaphor extends easily to life itself, with its ceaseless investments of effort and time in search of some elusive yield. In many cases, it resembles the contemporary obsession with early retirement—the dream of escaping the grind before its natural end. Yet once life reaches a certain point, expectation itself becomes unavoidable. We expect, and are expected, to have produced some yield from all that karmic labor: a crystallization, a residue, like butter coaxed from milk through its endless agitation. In this sense, ‘retirement’ turns back upon Shaowanasai, confronting him as one of Thailand’s seminal contemporary artists.4 These questions stem from the fiery urgency of his works, they press to anoint him as a venerable figure enshrined in art history, and they circle, too, with the desire to retire him from relevance altogether.

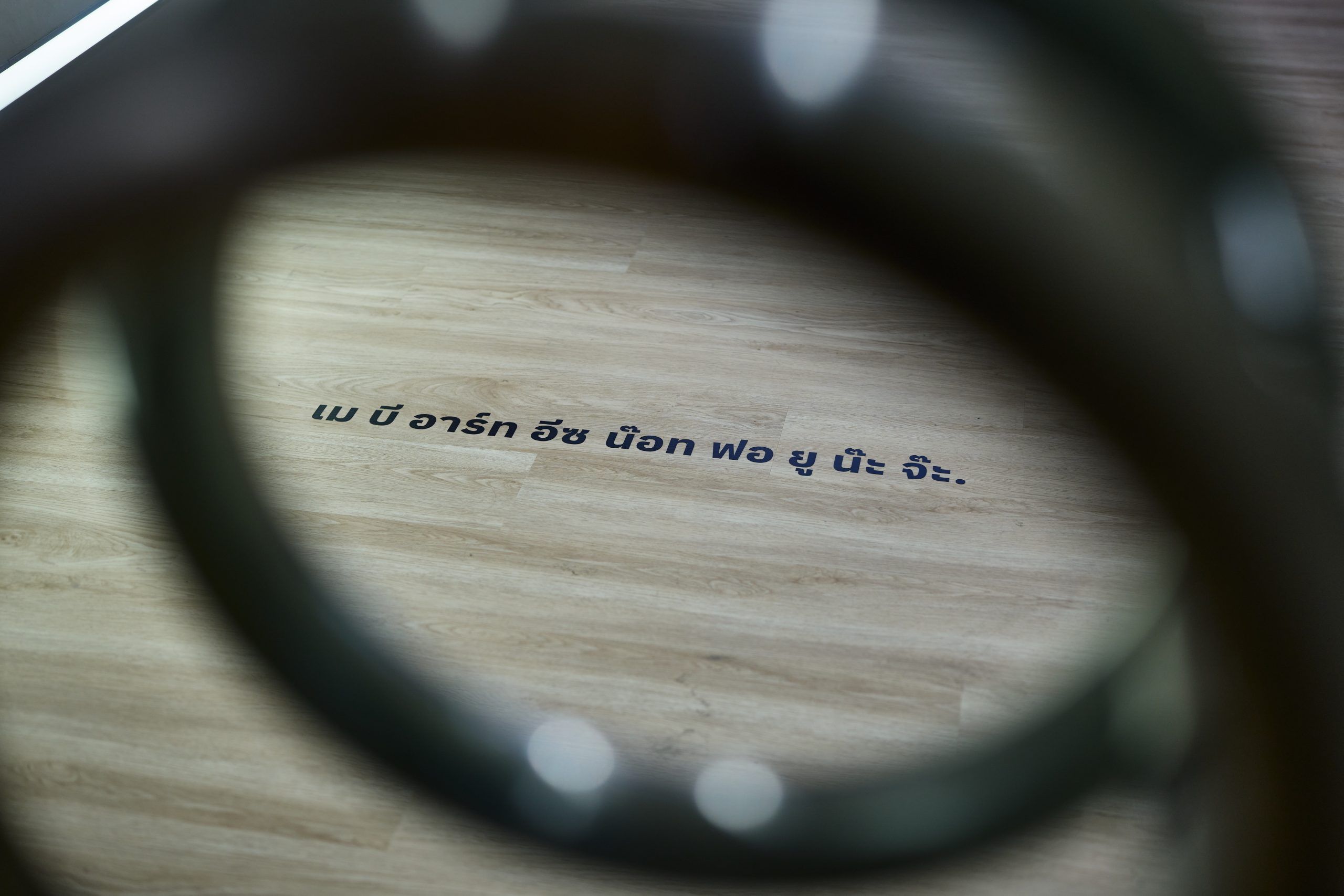

Throughout the exhibition, the space brims with ‘paratexts’ affixed to floors and walls, functioning like questions and answers that establish a kind of distance or frame around each work. Examples include karaoke-style transliterations of phrases such as ‘เม บี อาร์ท อีซ น็อท ฟอ ยู น๊ะ จ๊ะ’ (May be art is not for you, na ja – ‘Perhaps art just isn’t for you, dear’), ‘เล็ท มี เทล ยู ออฟ ว็อท ทู ติ้งค์’ (Let me tell you of what to think – ‘Let me tell you what you should think’), and, most striking of all, ‘เว็น ยอร์ พิ้วบ์ เทินท์ ไว้ท์ … ยู อาร์ เอ็กซเป็ก-เต็ท ทู โนว์ ซรรม ฌิฐ อเบ้าท ไล้ฟ’ (When your pube turnt white … you are expect-ted to know sarm shit about life – ‘When your pubic hair turns white, you’re expected to know some shit about life’). This last phrase appears beneath a quartet of photographs: close-up shots of a single white hair set starkly against black backgrounds.

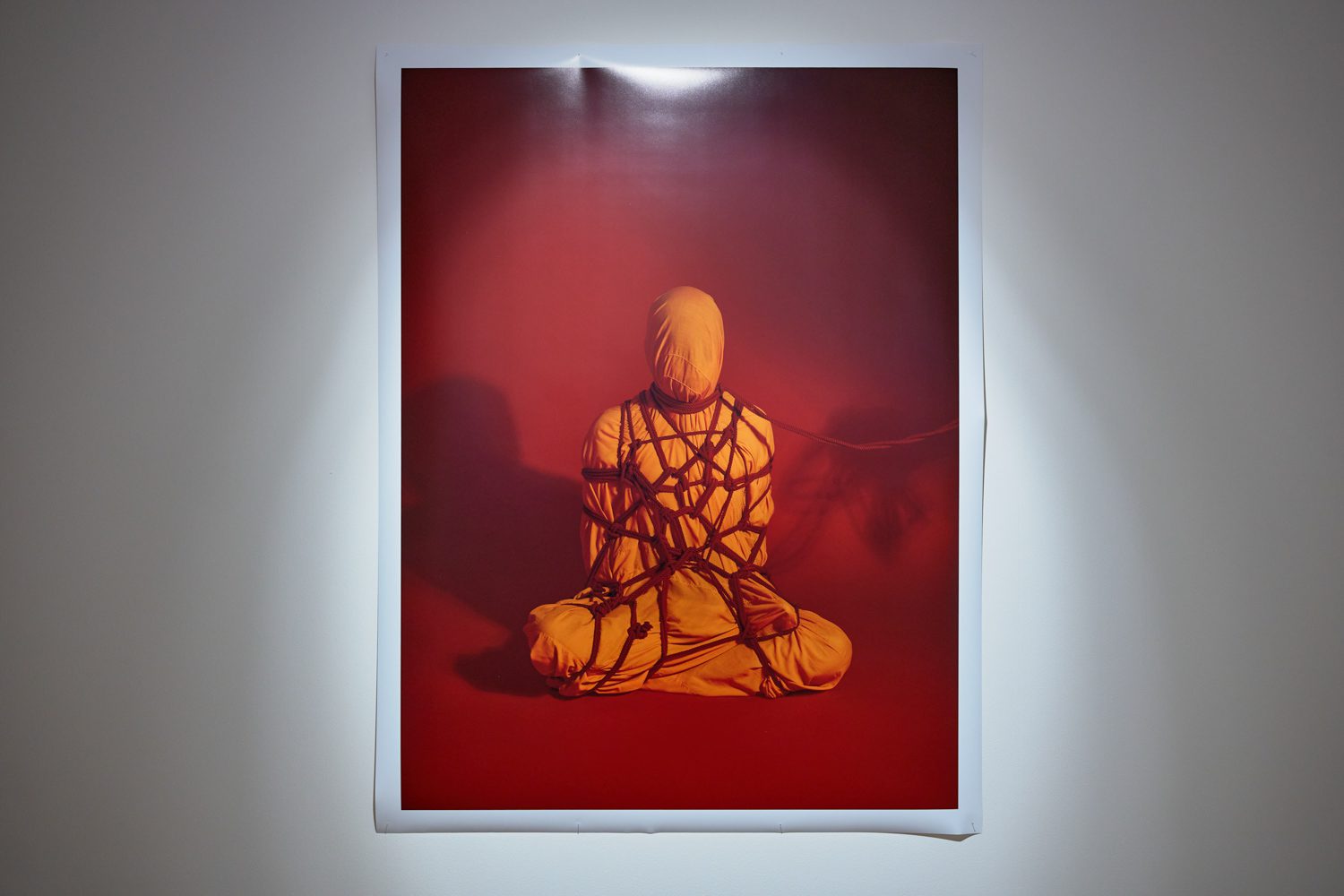

The theme of decline is pushed further, twisted into a meditation on degeneracy itself and its perennial promise of renewal. Just as the gods, weakened by the curse of the sage Durvāsas, had to rely on the nectar churned from the Ocean of Milk, so too the imagery of decline here crosses into another register: monks ringed by heaps of vice. Human figures are draped in saffron robes but bound in erotic knots of shibari. Holiness appears in tatters, faith depleted, waiting for reform, purification, and revival.

When the shibari-bound figures in robes are placed in the same room as the aging office worker with semen on his face, meanings that once seemed fixed begin to unravel. In reality, one need not wait for monks to be caught in ritualized bondage: even the mere ‘movement of semen’ is, according to monastic law, a grave transgression— a sanghādisesa offense.5 In one setting, semen is taboo, so forbidden that its mere flow marks sin. In another, it becomes life-force, joy, amrita itself, inseparable from creation, a natural condition of the body from which there is no escape. Shaowanasai’s work insists on this awkward dissonance of meaning: should we embrace it, suppress it, or reject it outright? Or is it all simply a matter of context, which works tirelessly to stratify, to order, to enforce difference on something that, in itself, carries no such distinction?

Shaowanasai’s photographs are never documents of ‘ordinary’ environments, nor attempts to capture, or to feign, the natural as if it were already there. They are setups—theatrical stagings closer to ritual drama performed on a stage or still-lives arranged in a studio. His images of monks, pushed so far off-script they verge on heresy, are not crude denunciations, not assaults on debased clergy delivered in the scolding cadence of a sermon on right and wrong. Rather, they beckon us to step back, to question the artifice, the staging, the selection, and, ultimately, the instability of meaning itself.

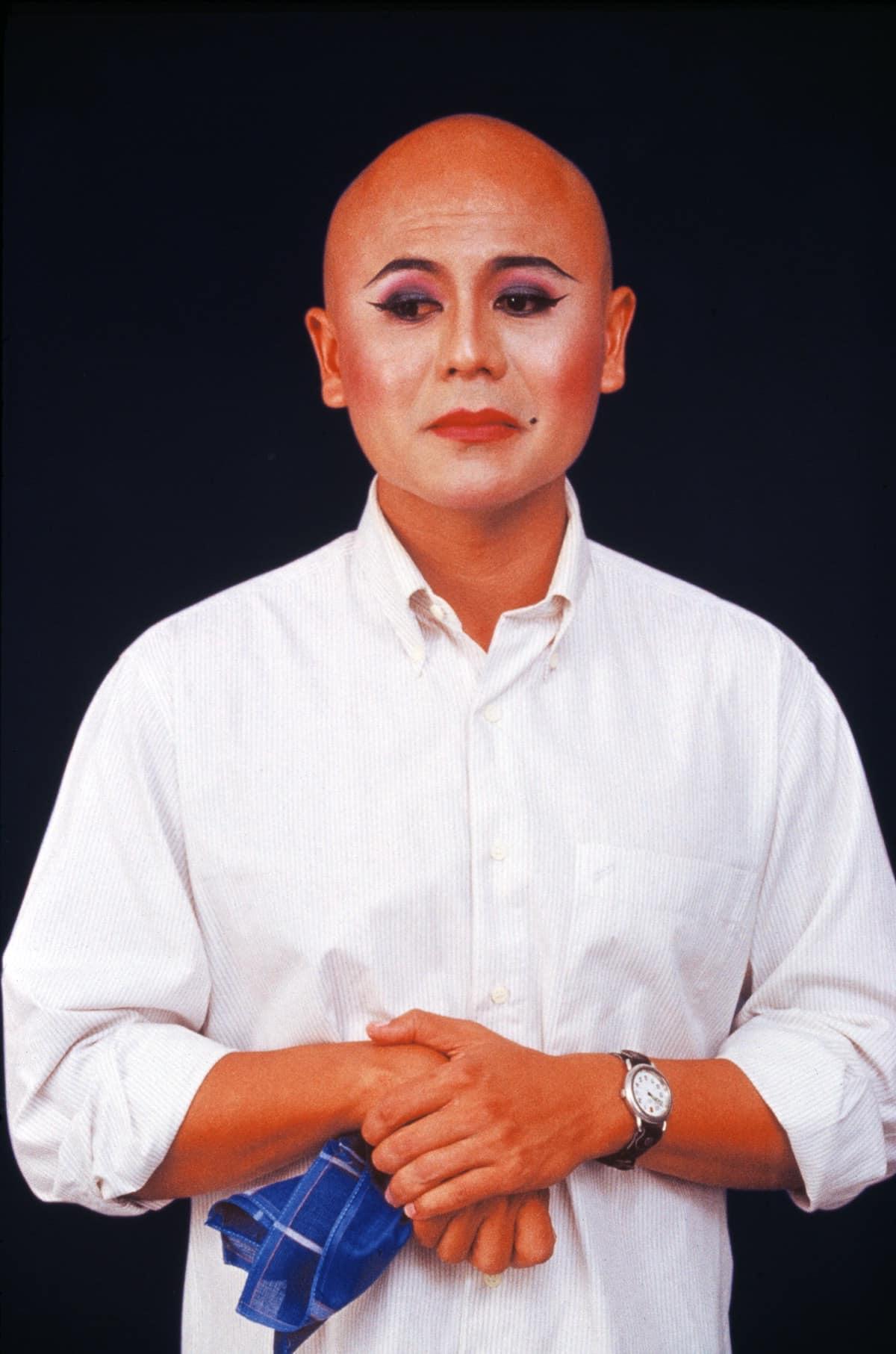

Semen and sexuality, in his work, fall in the sites where structures of authority struggle to regulate meaning. Once placed ‘out of place,’ they evoke embarrassment and unease, the awkward tension between taboo and unfamiliarity. Monastic codes demand the strict separation of sex from the domain of discipline. That same tension erupted two decades ago when Shaowanasai’s own ‘Portraits of Man in Habit,’ which are photographs of himself in monastic robes and heavy makeup, were exhibited in the exhibition, ‘alien{gener}ration (2000)’. The series drew fierce protests from devout Buddhists, forcing the organizers to remove the works from display. Shaowanasai responded with ‘Portraits of Man in Habits #2’: new photographs of himself clad not in saffron ropes but in plain white attire of a layman who has disrobed. His demeanor is subdued, even mournful, yet the cosmetics remain on his face, as if they cannot be scrubbed away.6 Art, it seems, continues to return to this question: what happens when things fall ‘out of place?’

Shaowanasai’s work unfolds in layers, yet those layers continually fold across one another. The aging male figure and the errant monk alike point to the instability of meaning. At each seam where meaning slips or drifts, questions arise from the impossibility of fixed coordinates; questions that never settle into definitive answers. Perhaps there is no need for anything to be fixed at all. Not because of vagueness or blur, but because of the very potential to flow, to shift, to remain alive. Like Shaowanasai himself, who refuses the patriarchal authority that guards sacred space, who refuses definition, who refuses retirement, and who even seizes upon amrita as a way of warding off decline.

And crucially, though semen may require a ‘ritual’ to be summoned forth, we know well that it need not appear only in the context of heterosexual union.

G’SEIN is on view at HOP – Hub of Photography, 3rd Floor, Seacon Square Srinakarin, from July 26 through September 21, 2025.

_

1 HOP Hub of Photography. “G’SEIN – เกษียร,” solo exhibition by Michael Shaowanasai. Facebook. Accessed August 19, 2025. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/reel/1396491618076597

2 King Vajiravudh (Rama VI). (1966). Lilit Narai Sip Pang [The Ten Incarnations of Narayana] (4th ed.). Bangkok: Khlang Witthaya. (First published 1923).

3 Parrott, R. (1983). A discussion of two metaphors in the “Churning of the oceans” from the Mahābhārata. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 64(1/4), 17–33.

4 Michael Shaowanasai has been recognized as one of the pioneering figures of contemporary art in Thailand through the exhibition “RIFTS: Thai Contemporary Artistic Practices in Transition, 1980s–2000s” at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, held from August 30 to November 24, 2019.

5 Somdet Phra Maha Samana Chao Krom Phraya Vajirananavarorasa. (1899). Navakovada. (Reprinted for distribution at the royal cremation ceremony of Mr. Thian Theerachaichayut, 1981), p. 3.

6 See more information about ‘Portraits of Man in Habits’ in Chanan Yodhong. Michael Shaowanasai’s ‘Luang Je’ and LGBTQ discrimination in religion. The Matters. Retrieved August 13, 2025. Available from https://thematter.co/thinkers/portraits-of-a-man-in-habit/92721.