THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE AL-MUJADILAH CENTER AND MOSQUE FOR WOMEN BY DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO REFLECTS THE FUSION OF TRADITIONAL MOSQUE TRADITIONS WITH CONTEMPORARY LEARNING SPACES FOR MUSLIM WOMEN

TEXT: PRATCHAYAPOL LERTWICHA

PHOTO: IWAN BAAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

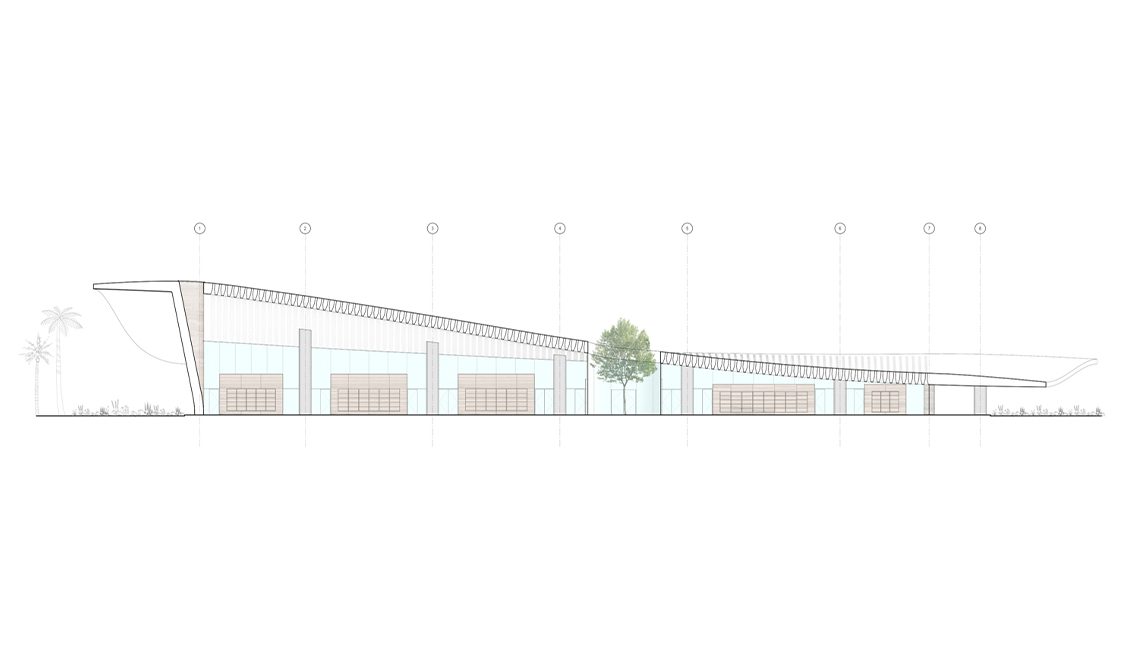

Rather than evoking the conventional image of a domed mosque encircled by slender minarets, this project takes the form of a single-story structure that merges seamlessly into the desert landscape. Beneath an expansive white roof that rises in a gentle, wave-like curve reminiscent of shifting sand dunes stands the Al-Mujadilah Center and Mosque for Women in Doha, Qatar, a reimagined vision of the mosque as a contemporary space dedicated exclusively to women.

Located on the western outskirts of Doha, the complex sits within ‘Education City,’ a 12-square-kilometer district that brings together universities, research institutions, and cultural venues. Conceived as part of Qatar’s national effort to chart a future less reliant on oil and natural gas, Education City has drawn commissions from some of the world’s most renowned architects, including Arata Isozaki, Grimshaw Architects, OMA, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the firm behind the design of the Al-Mujadilah Mosque itself.

The idea for the mosque originated with Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, Chairperson of the Qatar Foundation, who observed that spaces for Muslim women to worship were often limited and lacked the dignity afforded to those for men. Al-Mujadilah was thus conceived as the first women’s mosque in the Muslim world, a symbol of reform that envisions the mosque as an open, inclusive, and contemporary space. Its distinctiveness lies not only in its progressive vision but also in its architecture, which reinterprets the traditional typology of the mosque. While the sweeping roof follows the grid of Education City, the layout beneath aligns with the Qibla, the sacred direction faced during prayer, adhering to the mosque’s traditional orientation. At the heart of the building lies a glass-enclosed courtyard that contains two olive trees. Evoking a contemporary yet graceful reinterpretation of the traditional mosque courtyard, the olive courtyard organizes the interior into two principal zones: a library and a prayer hall.

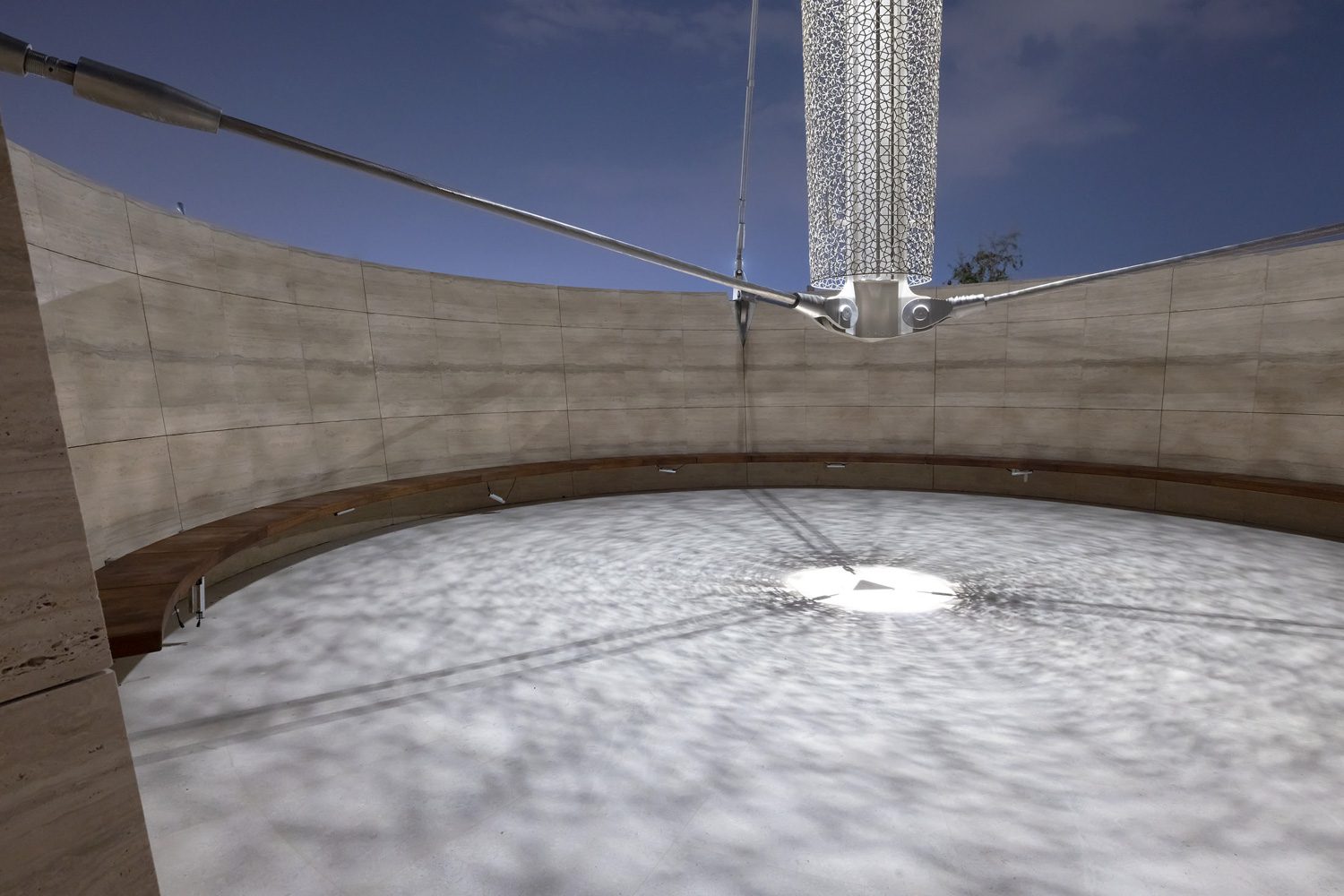

The prayer hall spans more than 875 square meters and can accommodate up to 1,300 worshippers. At the far end, the eye meets a travertine wall marked by two striking concave recesses. One defines the position of the Minbar, the pulpit, reinterpreted here as a slender sheet of blackened steel; the other forms the Mihrab, which indicates the Qibla direction. While traditional mosques often adorn the Mihrab with elaborate ornamentation, the one here is deliberately restrained yet profoundly expressive. The roof subtly lifts above it, allowing natural light to cascade down the stone wall in a play of illumination and shadow. The floor is covered with a large handwoven wool carpet made from New Zealand wool, its pattern derived from the enlarged motif of a Turkish prayer rug. The resulting pixelated effect lends warmth and intimacy to the vast, open space.

Photo: DSR

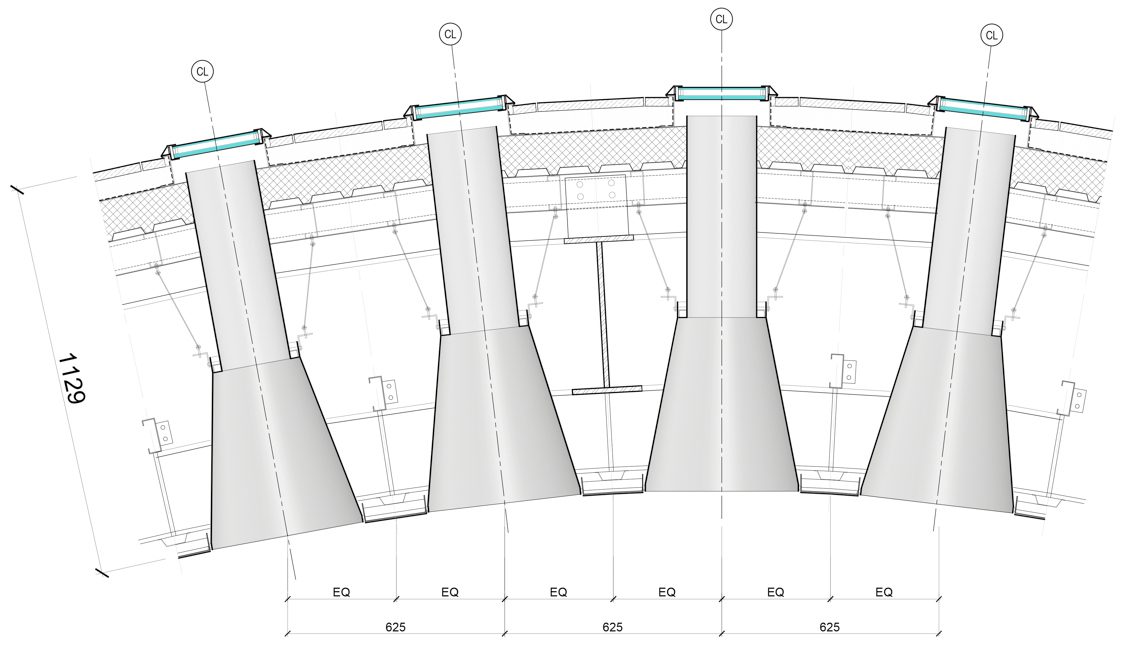

Though it departs from the conventional dome-topped silhouette, the building subtly carries forward the mosque’s architectural essence through a sweeping, undulating roof that rises above the prayer hall and gently slopes downward toward the library on the opposite side. This dynamic form creates a spatial contrast between an airy, expansive prayer hall designed for large congregations and a warm, intimate library that invites quiet reflection. Across the roof’s surface, more than 5,000 circular skylights diffuse natural light into the interior, bathing the spaces in a soft, even glow while minimizing heat penetration.

The prayer hall and library form the heart of the complex, surrounded by supporting functions such as classrooms and a café. This spatial arrangement reflects the founding vision of a mosque that transcends its role as a place of worship to become a center for learning and the empowerment of Muslim women. The travertine walls that define these spaces not only lend a sense of calm and continuity but also allow the building to blend harmoniously with the surrounding desert landscape.

The call to prayer resonates through speakers mounted within a reimagined minaret, a 39-meter-tall tensegrity steel tower woven into an intricate lattice. Its mesh-like pattern recalls the delicate perforations of mashrabiya screens, the carved wooden balconies characteristic of Islamic architecture. At the appointed time, the speakers ascend automatically to the tower’s peak, their sound carried softly across the landscape, which is enveloped by vegetation and sand mounds that ensure privacy and buffer outside noise.

As faith and society continue to evolve, Al-Mujadilah invites reflection on how religious architecture need not remain bound by tradition. Instead, it can return to its spiritual roots while embracing contemporary life with both grace and relevance.