BAAN VELA IS A HOUSE DESIGNED TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM OF DENSE URBAN SPACE BY BORROWING FROM NATURAL LANDSCAPES AND ENHANCING THE QUALITY OF LIFE, BY PH/AD

TEXT: XAROJ PHRAWONG

PHOTO: DOF SKY|GROUND

(For Thai, press here)

Architects around the world have proposed a wide range of approaches to housing design within the dense fabric of major cities. Some turn inward, creating layers of private space rather than opening directly to the outside, while others reinterpret urban living by inviting nature to mingle with interior spaces. As technology continues to advance, architectural solutions we encounter grow increasingly complex and diverse. Yet, regardless of the form these responses take, the fundamental principles that have guided architectural design for centuries remain indispensable and cannot be set aside.

In Japan, where architecture is often conceived on extremely limited plots of land, a technique known as ’shakkei’ (借景), or ‘borrowed scenery,’ has long been employed. This approach appropriates the surrounding landscape as part of the architectural composition itself. Even when a building is small and constrained by tight boundaries, carefully positioned openings and wall planes set at eye level allow a modest garden within the house to merge seamlessly with the natural scenery beyond its site. Through this subtle strategy, ’shakkei’ offers an elegant solution to the challenge of connecting architecture with nature on narrow urban land.

Within a design approach that takes problems as its point of departure, architecture is conceived through a mode of direct response and problem-solving. This method begins with a clear reading of the constraints and challenges embedded in the brief, followed by the formulation of solutions shaped by the specific context in which the architecture exists. Vela House exemplifies this way of thinking. Designed by PH/AD, the house is located in a decades-old residential estate in the Seri Thai area, with its rear boundary adjoining Bueng Kum Public Park. In response to the brief, the architects conducted a careful survey of the surrounding environment, studying the site from elevated viewpoints in neighboring houses. This process revealed the latent potential of the park landscape at the rear of the plot.

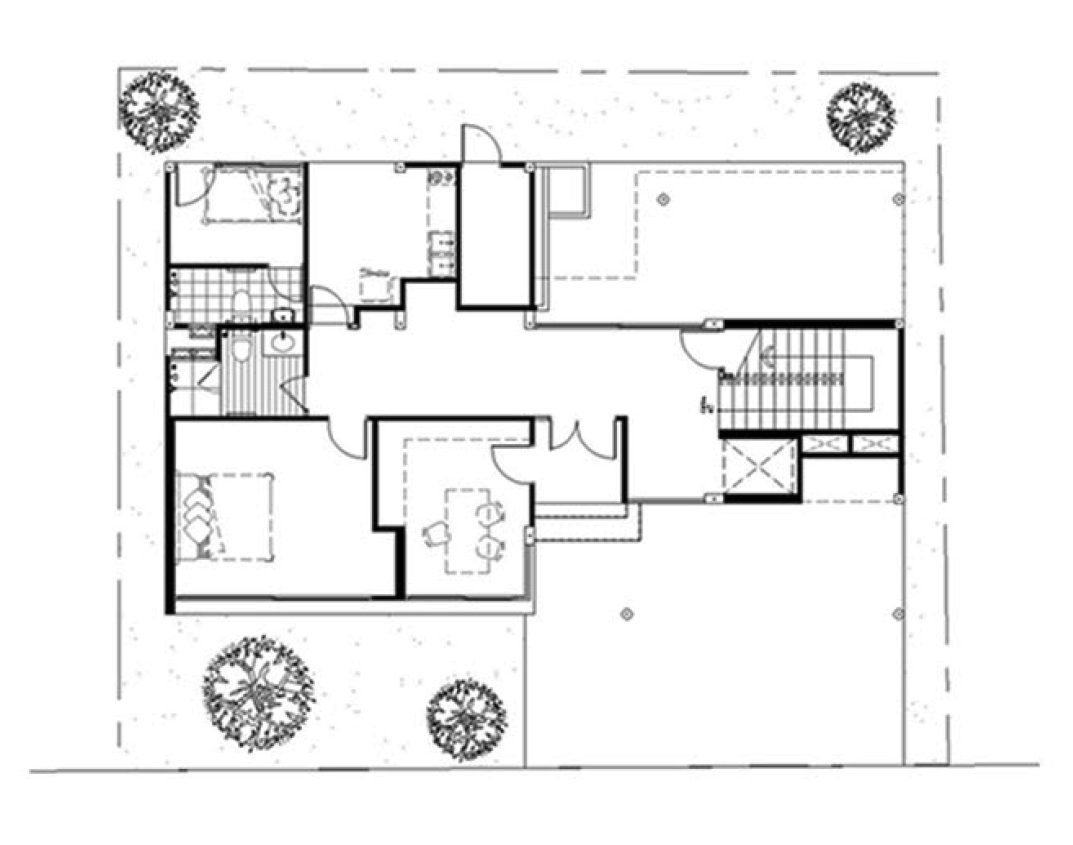

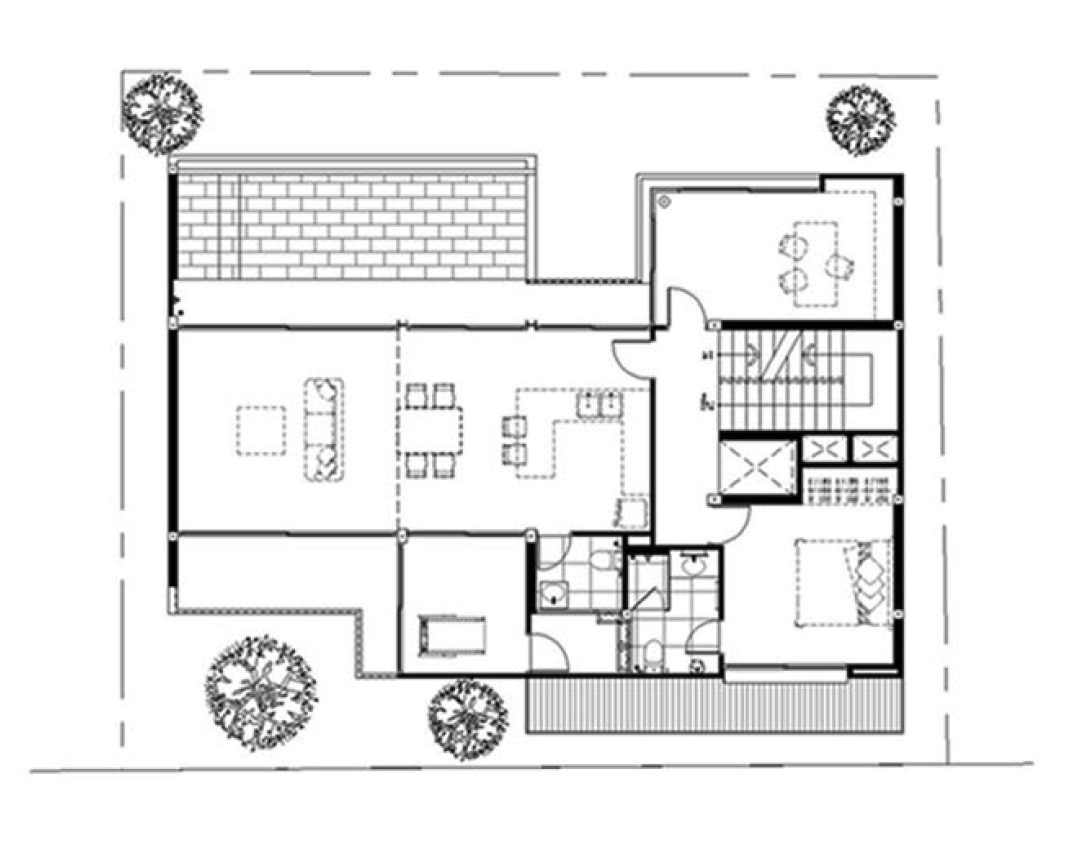

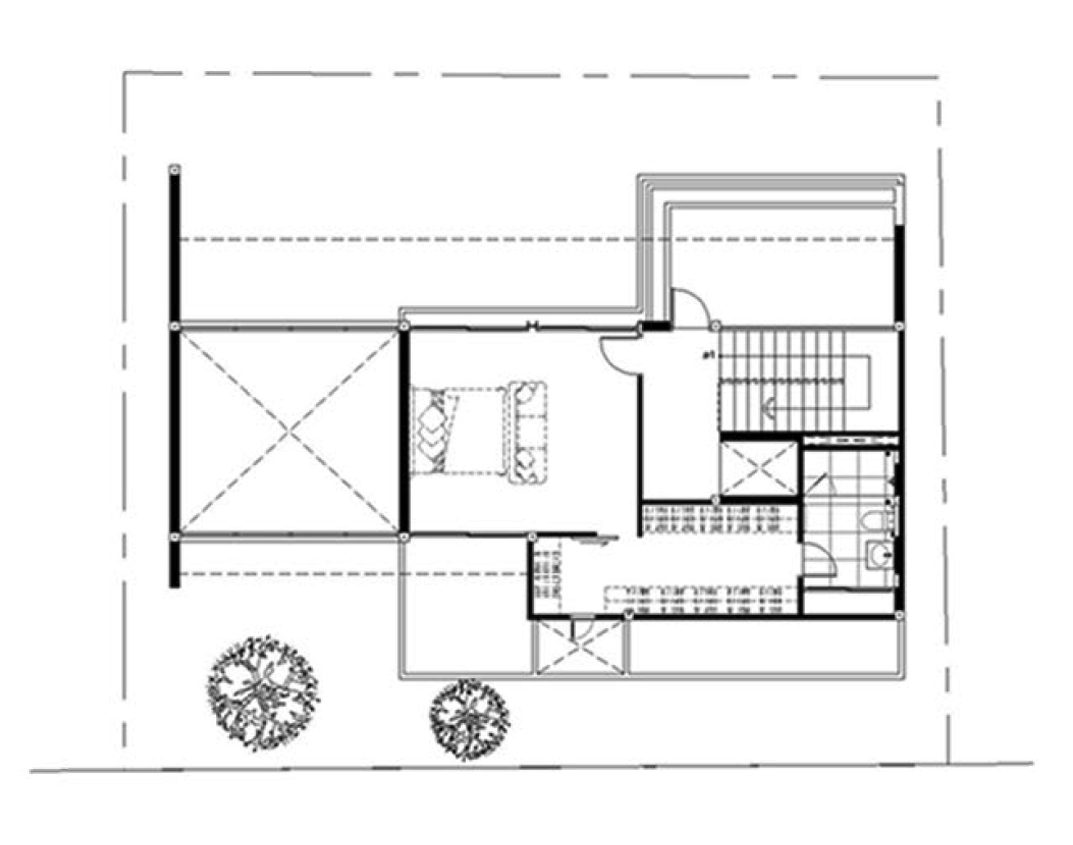

The design strategy therefore centers on drawing in this borrowed view from the park, a landscape unlikely to change over time. Above the boundary fence, the visible canopy rises to the height of approximately four storeys, prompting the architects to locate the home’s primary living spaces on the second and third floors. The ground floor is reserved for service functions, including workspaces, maid’s quarters, pool systems, and building services. The interior atmosphere is shaped to encourage constant interaction among its occupants. The main living lounge and swimming pool are positioned as the heart of the house on the second floor. This central space is conceived as a special double-volume area, enclosed by a fully glazed wall that opens vertically across two storeys. Elevated above the rear boundary wall, the treetops of Bueng Kum Public Park are drawn directly into the interior, becoming an integral part of the living experience. At the same time, this layer of foliage acts as a natural filter, softening the intense western sunlight in the afternoon. The resulting image of the main living space stands in deliberate contrast, a dialogue of solid and void, juxtaposing the uniformity of the housing estate across the street with the lush natural backdrop of the park beyond.

While drawing in the view from the adjacent park lends the house a generous and uplifting atmosphere, a closer reading of the building reveals a largely solid and enclosed exterior envelope. This condition stems from a programmatic necessity, as many of the perimeter zones are occupied by bathrooms that require a high degree of privacy. Each bathroom, however, is carefully resolved to ensure proper ventilation and access to daylight for hygiene and comfort. Small courtyards are inserted between the outer envelope and the bathroom walls, paired with strategically placed openings that allow natural light and air to enter. As a result, the building’s skin becomes a direct expression of its internal functions, closing itself where privacy is required, while opening upward to the sky to engage with natural phenomena.

This clarity and directness in translating interior use into exterior form also informs the material strategy of the house. Natural materials are prioritized, with stone veneer serving as the primary material throughout. Applied seamlessly from exterior to interior, the stone veneer establishes a continuous material language across the entire house. From within, this continuity is strongly felt, reinforcing a sense of cohesion. Where shifts in function need to be articulated, other materials are carefully introduced, such as the pairing of stone venee with timber or different tile finishes in the bedrooms.

If architecture is ultimately about elevating quality of life, then design, in this sense, becomes first and foremost an act of problem-solving, one that takes precedence over questions of style or decoration.