GLASS PLATE NEGATIVES: STORIES THAT TRANSCEND TIME, FEATURES WORKS OF PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY AND THEIR ENTOURAGE. CAPTURED ON GLASS FILM, THE 102 PHOTOGRAPHS TELL STORIES ENCOMPASSING THE PERIOD BETWEEN THE REIGN OF KING RAMA IV AND KING RAMA VII

TEXT: NUTDANAI SONGSRIWILAI

PHOTO COURTESY OF BACC

(For Thai, press here)

A photograph works like a tool that captures and documents the past, preserving its existence. Every time an image is viewed, a story or a captured moment resumes its course, creating another reality within its own premise. A presentation of a historical photograph is, therefore, a presentation of evidence or a memoir, but they all are a type of apparatus that proves the existence of the past. In a situation where images are put on display, moments and periods in history are pulled back, superimposed in the present and telling other parts of a story for viewers of the current time to rebuild the past, as pieces of yesterday gradually complete the picture of the present.

Glass Plate Negatives: Stories That Transcend Time, an exhibition at the Art and Culture Centre, features works of photographs taken by members of the Royal Family and their entourage. Captured on glass film, the 102 photographs tell stories, which are split into 4 different parts, encompassing the period between the reign of King Rama 4 and King Rama 7. Each part is given a different title from Patombun (the first part) to Jatutathabun (the fourth part), telling stories from King Rama 5’s journey to rural areas of Thailand, people’s way of life in the time when Bangkok saw an influx of western culture, to the final part featuring the photographs taken in the period when Siam went through progressive developments.

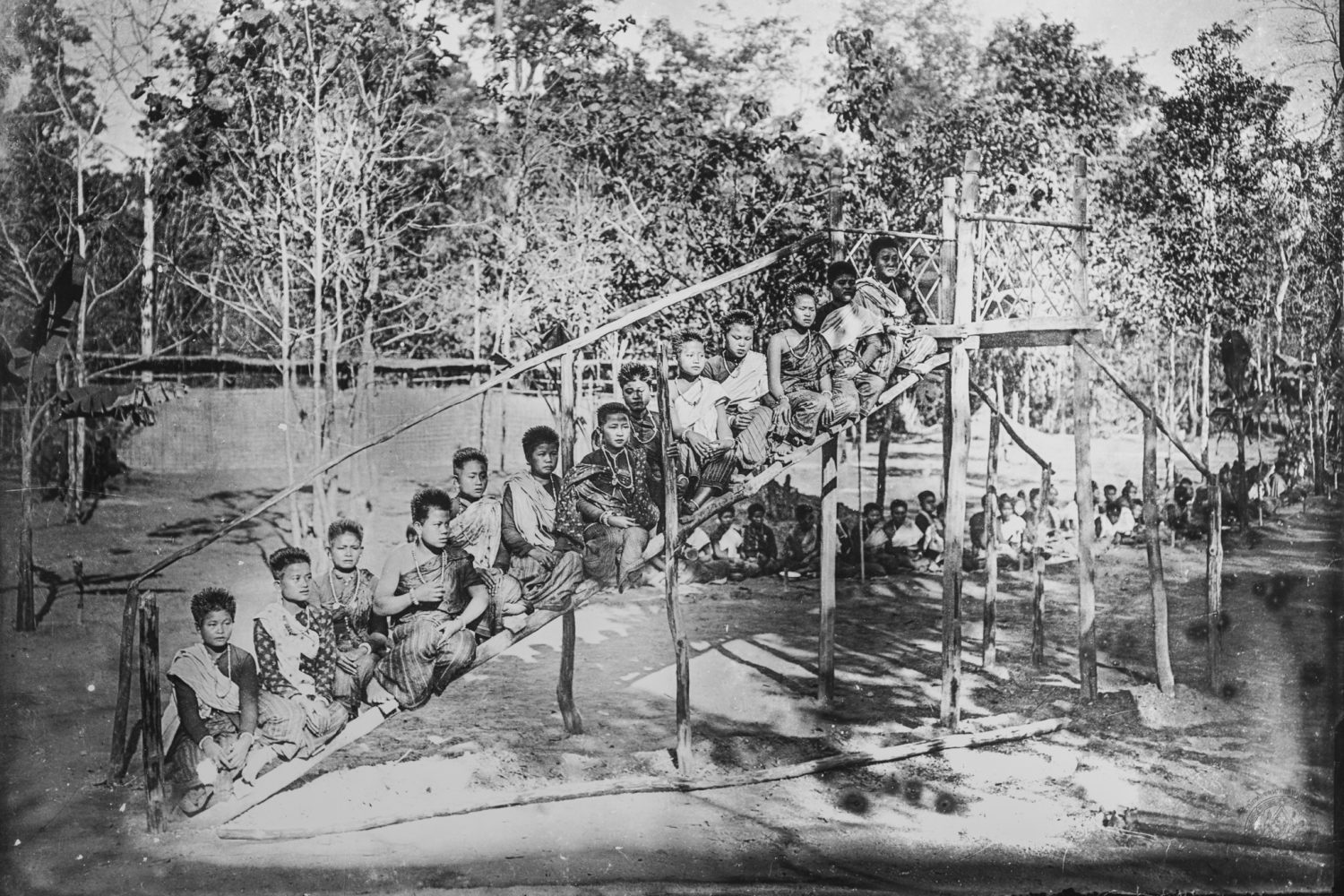

The first part of the exhibition or ‘Patombun’ tells the story of King Rama 5 and the time when he traveled outside of the capital, depicting images of locals’ way of life, as well as the photographs of the people taken by the king himself (with every person in one of the pictures looking straight at the camera), the all-white shirts they wear (or perhaps it’s because the pictures are black and white). Unfortunately, the identities of the people in those captured images were untraceable.

Leaving the first exhibition room, viewers would come across another set of photographs occupying a curved wall (this is the first area where viewers start their walkthrough of the exhibition). The camera captured the period during the journey where members of the royal family pretended to be the followers of Praya Boranburanurak who were conversing with the locals. Thanks to their undisclosed identities, the members of the Royal Family were able to wander around and take pictures from other different angles. Adjacent to the wall, another series of photographs are displayed, portraying the King’s misery from the loss of his own sons and daughters, before ending the period of the journey and the first part of the exhibition.

Another observation that should be made and documented in this article is the hole in the wall where viewers are able to walk through and enter the second part of the exhibition. The second circulation then begins, in addition to the one running along the curved wall. This benefits the viewing experience a great deal for it links the last photograph of ‘Patombun’ to the first photograph of “Tutiyabun” in the second part of the exhibition, which perfectly depicts the way of life and everyday surroundings found in Bangkok.

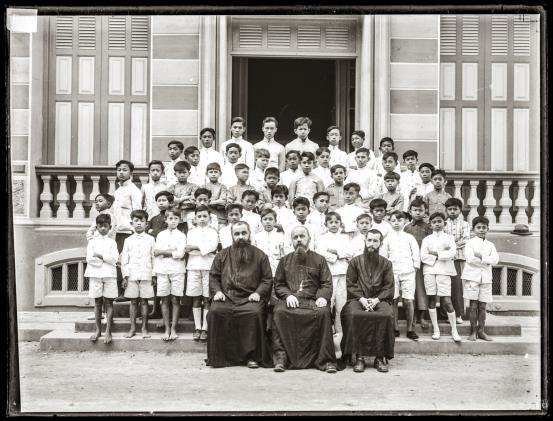

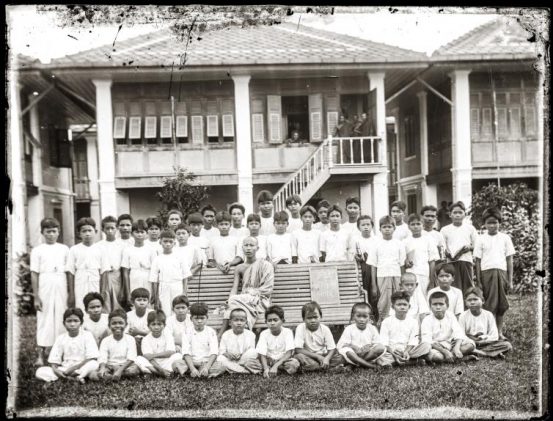

The next part, “Tatiyabun”, consists of photographs illustrating the arrival of western culture in Bangkok, depicting differences between the two social classes, the Thais and foreigners who had just settled in Siam, from the image of a swimming pool at the Royal Turf Club of Thailand to those of Y R Andre Department Store known for its pre-ordering services for imported products and car dealerships, which were considered very new businesses at the time in Thailand. The best depiction of the ‘differences’ is the three photographs exhibited next to each other on the curved wall. They were group pictures of students; one of the students of Saint Gabriel College (where the majority of students were non-Thais and obviously wearing school uniform). Another one is that of the students of Bali Waiyakorn School (dressed in polite attires but not uniforms). The next photograph is another group picture of the students of Wat Sung Nok Temple School where sons and daughters of members of the royal family as well as the personnel working under the office of Princess Suddhasininat Piyamaharaj Padivaradda. These photographs reflect the differences in educational systems between the upper class and the commoners, including the norms about sexuality, social classes, rights as well as student uniforms, which up until this day, is an issue that is still up for debate in Thai society. The exhibition’s curator, Sirikitiya Jensen, takes and interesting approach to clearly and interestingly illustrate such differences.

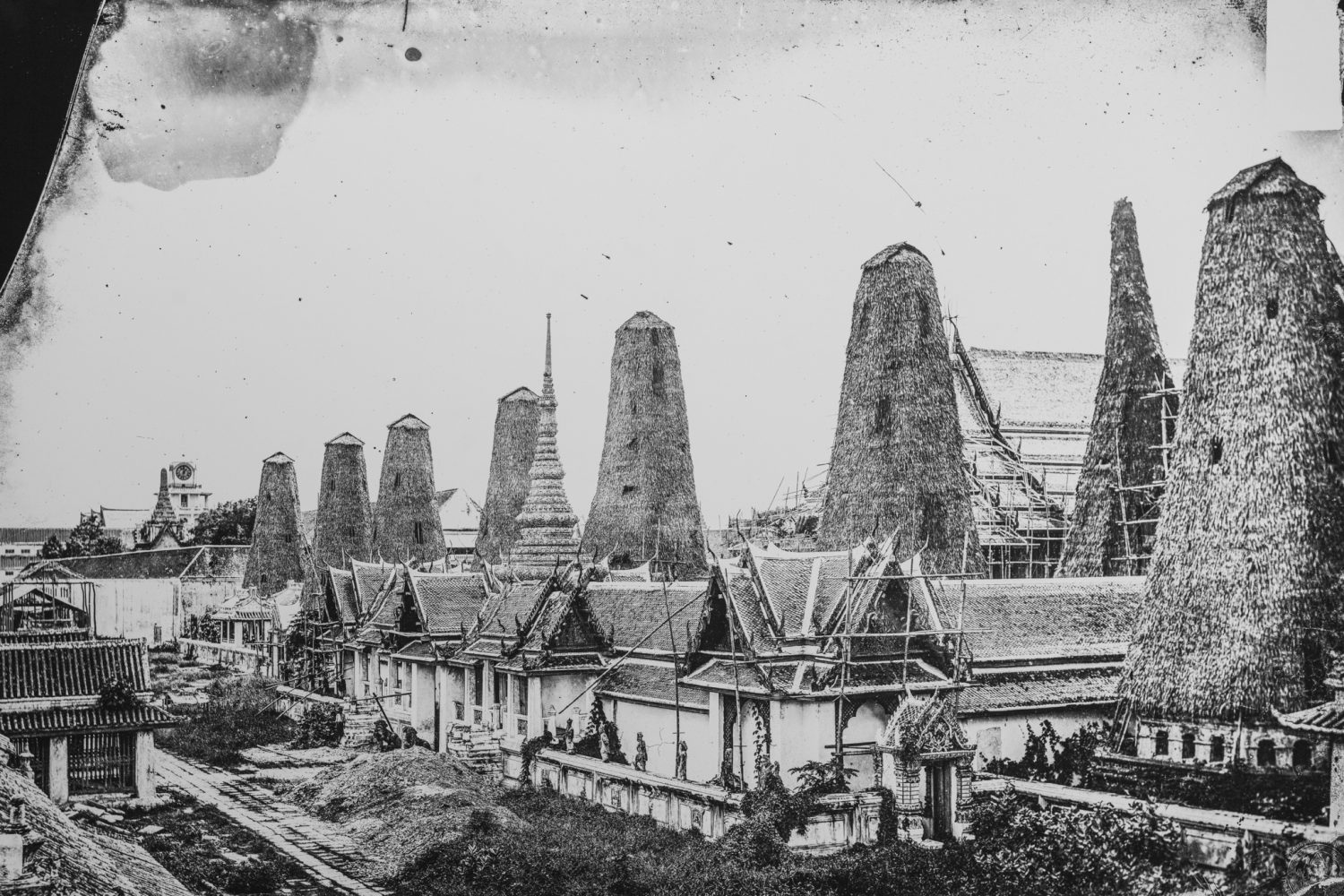

The last part, “Jatutathabun”, portrays the new developments succeeding the aforementioned period, such as the photographs of the Bangkok’s Train Station, a series of photographs of the construction of Chalermkrung Pavilion, from the model until the completion of the project. The exhibition also places more focus on archaeological works through the photographs of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab’s visits to a number of ancient sites such as Temple of Preah Vihear or the controversial ancient Naraibantomsin stone work placed on a pile of stone before it was illegally removed. This part of the exhibition is mostly comprised of the photographs taken during the Prince’s visits to rural towns across the country, while a number of pictures of temples and Buddhist monks are presented with only very few additional information.

Reaching the end of the exhibition, if we turn back to have a look, appearing before our eyes are a large number of photographs intertwined, creating a specific story and dimension within this contemporary space. The past makes its way to the present, but with a new set of historical meanings that has been viewed and recreated by the viewers. The time that was once still, starts moving again with the eyes of the present. Looking into each photograph with a perspective where the past and present are superimposed, we are required to reread, going back and forth, and learn that there are great differences viewed by varying pairs of eyes. This very same exhibition may tell a different story to each viewer. Stories exist throughout time, traveling back from the past, being retold and recounted from the eyes of the various viewers. The past and present are perhaps colliding; a parallel dimension that is running its course from the beginning to the end of the exhibition.