ART4D TALKS WITH JOE – APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL ABOUT MEMORIA (2021) WHICH RECENTLY WON THE CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 2021’S JURY PRIZE, AND HIS LATEST EXHIBITION, ‘A MINOR HISTORY, A LITTLE HISTORY’ AT 100 TONSON FOUNDATION, AS WELL AS THE STORIES OF HIS CAREER AND THE FUTURE

TEXT: PRATARN TEERATADA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

I first met Apichatpong Weerasethakul or Joe for the first time at his office, Kick The Machine, in Ladprao, Bangkok around twenty years ago. He was young and overflowing with many dreams; it’s kind of like the energy we tend to see from young aspiring start-ups today. He would write up proposals and send them to people and organizations around the world with hopes to get funding for his projects. He even wrote to George Soros once. “I’m still doing that these days.” The Joe I see today is still polite and humble. The tenacity and passion he has to achieve what he believes in has come into fruition. It has been personally fulfilling and the journey has given him his own cinematic language that has taken his storytelling to the point of global recognition, and deservingly so.

Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai, ©100 Tonson Foundation, 2021

Just last month, he gave a speech at the Cannes Festival with the compelling phrase ‘Long Live Cinema.’ Throughout the twenty years of his career, Apichatpong Weerasethakul has achieved many international successes and milestones. Just at Cannes alone, one of the world’s most revered film festivals has selected eight of his films for its official selection, three in the Official Section, two in Un Certain Regard and three in Special Screening. He’s won four awards in total; Un Certain Regard prize for Blissfully Yours (2002), Jury Prize for Tropical Malady (2004), Palme d’Or for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) and another Jury Prize for Memoria (2021).

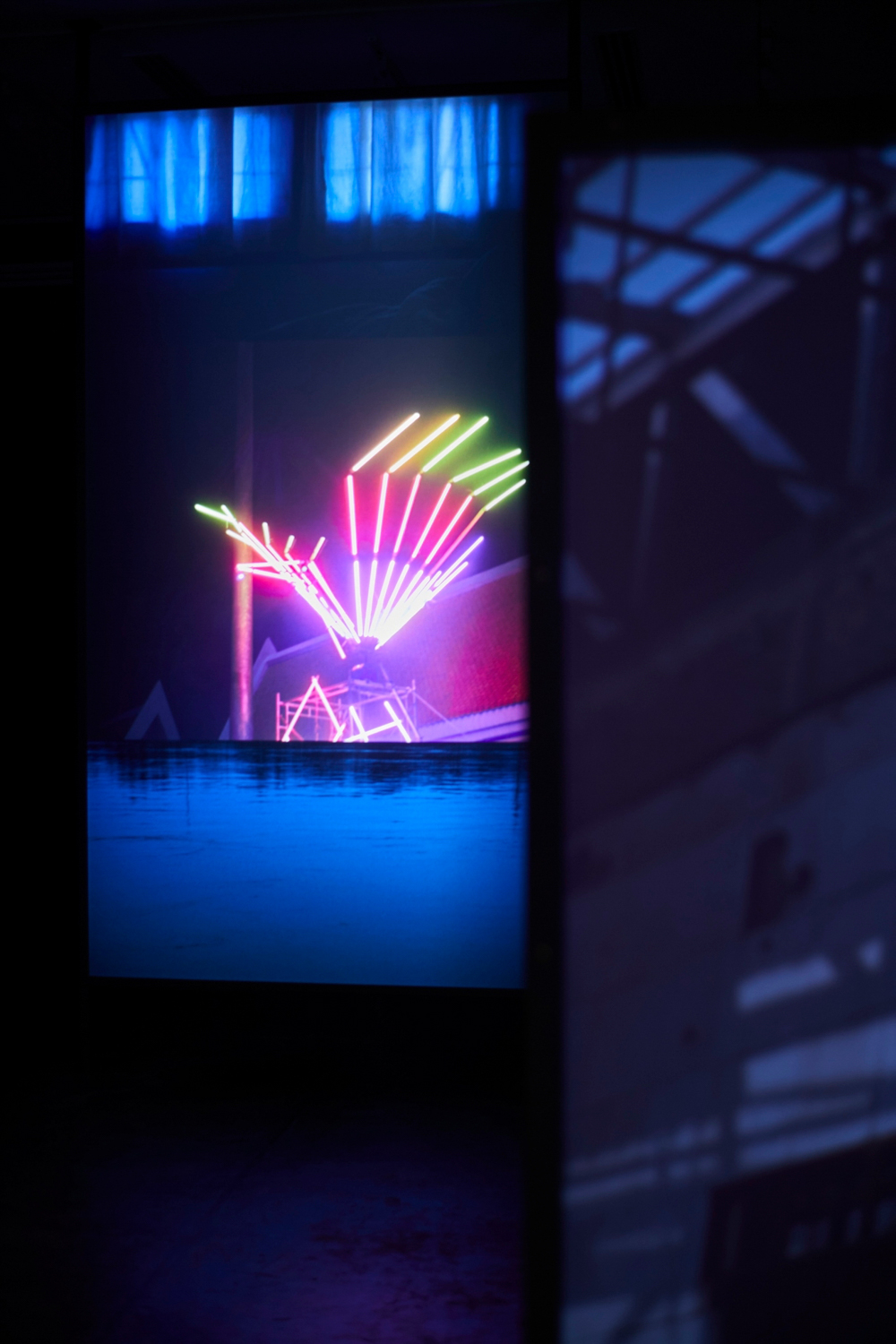

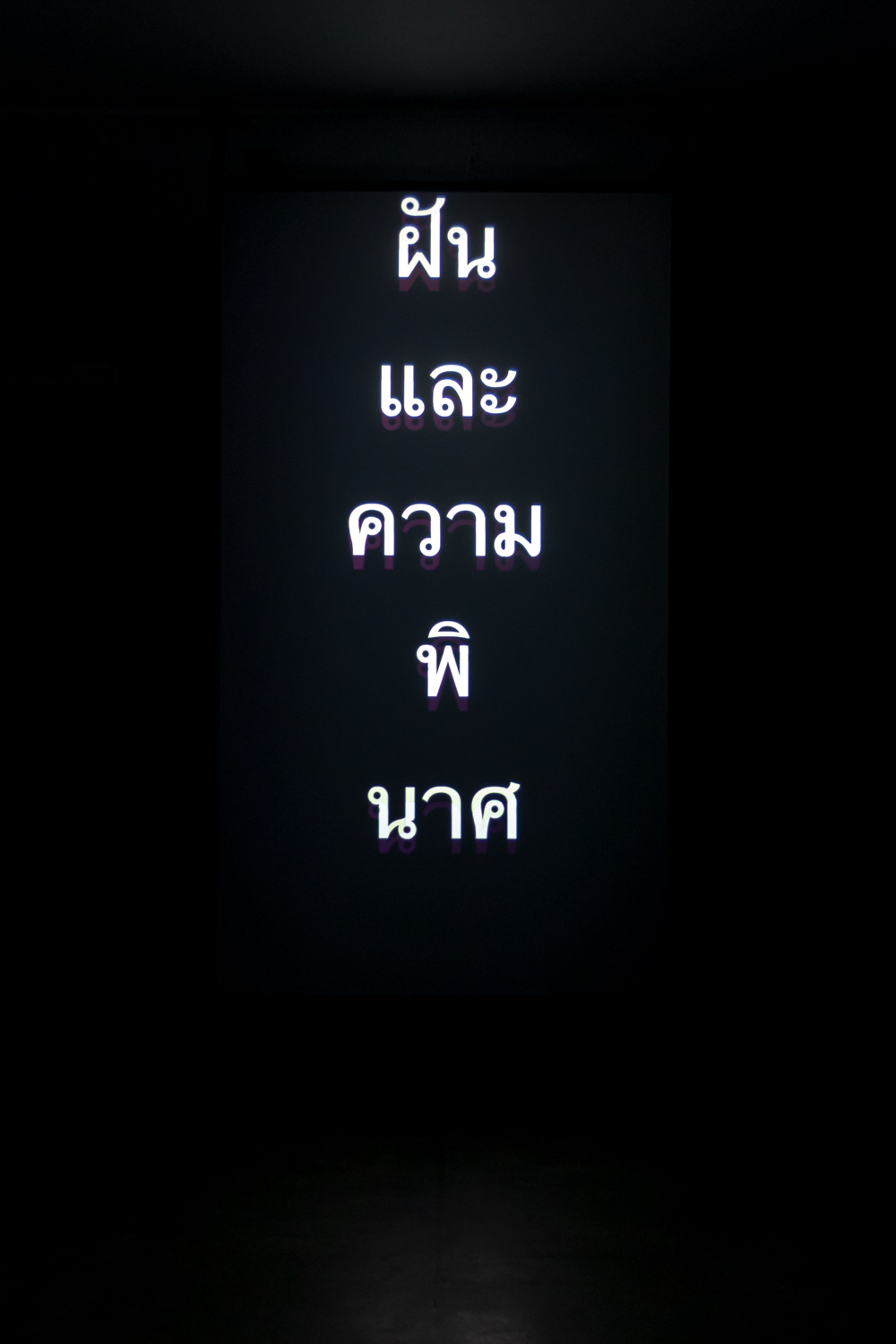

Joe is currently hosting ‘A Minor History’, an exhibition of video installations at 100 Tonson Foundation. He divides the series into two parts with the first part now showing from August 19th to November 14th, 2021. In our latest conversation, I congratulated him on his new film, Memoria, and the exhibition. We talk about his inner journey and its connection to his art and filmmaking. “Everything feels like a dream. It feels so surreal,’ Joe mentions as he articulates his thoughts about his life in these past twenty years.

art4d: Congratulations on Memoria. I was following your news at Cannes and it seemed pretty hectic since you had all these activities and press junkets, not to mention meeting media people and celebrities. Now that you’re back here, in Bangkok, when the city is still under lockdown, which is a completely different atmosphere from where you previously were. How do you feel, deep down?

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: It is different, obviously. It’s like Europe and Thailand are functioning at different paces now. Time seems to stay still here in Thailand because of the failure of vaccine management and the political situation. It feels like I’m starting over again and time goes by very slowly. In Europe, I was talking to a lot of people about several projects, and I was planning to go to quite a few places, but when I returned here, it’s like returning to the real world where there are issues about vaccine shortages and the underprivileged. I need to adjust and slow myself down a bit too. I’ve also been helping Sakda Kaewbuadee (Tong) with his refugee activities, which is pretty much like his main job now. Compared to Europe, my life here is definitely moving at a slower speed. But at the same time, I know that this country has always been an inspiration to me. With ‘A Minor History’ including the second part of the series I’m about to work on, it’s like coming back to the real world where the system that provides cultural support isn’t as strong and thriving as in Europe. If you ask me what I have been doing after Memoria, I guess I have honestly been adjusting.

Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai, ©100 Tonson Foundation, 2021

art4d: The day you left Cannes, were there any words, feelings or incidents that stayed glued in your memories, events or moments that you still think about even now when you’re far away from that place?

AW: It felt so surreal, everything about the whole experience. From having my film screened in front of a thousand people to when Tong told me about how young people use my words, ‘Long Live Cinema,’ as a way to express hope. I think that phrase hit me in the way that I haven’t really thought about the importance of what I do because to me it’s always been very personal. Throughout our conversations in these past twenty years, we’ve talked about how everything I’ve done is personal. It makes me realize that what I do has more of an impact than I thought it would have. It stunned me. When I left Cannes, I felt like I wasn’t alone anymore. There’s a sense of connection now. When I create work and it connects to the movements that are happening in a society when in fact, my films and society aren’t actually that interconnected.

art4d: As someone who hasn’t seen the movie yet, I’m hoping that I will get to see it in cinemas later this year or the beginning of next year. At this point, I’ve only seen Cemetery of Splendor recently at Thai Film Archive, because your films can only be viewed only in cinemas, on the big screen. The reviews I have read about Memoria talk a lot about the viewing experiences that audiences get from the design of visuals and sounds, and how it elevates the cinematic experience to the next level.

AW: It actually originated from the voices in my head. It’s a symptom called Exploding Head Syndrome (EHS), which isn’t exactly a noise but the feeling of the noise. It’s like when you hear yourself thinking, not through your ears but from the sounds inside your brain. It’s the same with Memoria. It was a period when I was travelling in Columbia and I used that experience to talk about the violence and people’s memories, through the violence, and the explosive sounds. In reality, its a very simple movie. It takes place within the span of a few days during the woman’s journey, where she is constantly attacked by this particular sound.

art4d: Could you tell us a bit about how you mix sounds with visuals to create this unique experience?

AW: I don’t know how to explain it, really. Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr (Rit) was the one who worked on the sound mixing with me, we both focused on the details of the sounds inside and outside of the frame. If you look at Cemetery of Splendor or my previous films, the focus is the same. But Memeria’s story progresses with this condition that the main character feels like she’s hearing something all the time, and that automatically is what the viewers have to experience. That’s why they hear all these details when in fact the process isn’t that much different from other films. The film tunes the audience in, somewhat guiding them through the excessiveness of sounds within different spaces. What we designed works well with the atmosphere inside a cinema. But what’s actually challenging is finding the explosive sound, and figuring out how to design it because it isn’t exactly a sound. There’s a scene where Tilda (Tilda Swinton, the film’s lead actor) tries to explain what she’s been hearing to the sound mixer about and they try listening to different types of sound.

art4d: Did Tilda hear the same sound you did?

AW: Not at all because the sound was created later in the sound mixing studio.

art4d: When you were filming in Columbia, did you have any experiences you want to share as a filmmaker with a background in architecture?

AW: There was a moment in time when I was experiencing this rumbling sound inside my head and soon I began to see images. When I closed my eyes, there would be a circle or a rectangle appearing. These shapes would pop up along with the sound, especially the circle. In Columbia, there are architectural structures that are in geometric patterns and they have these Brutalist characteristics. They’re massive, concrete structures with beautifully designed openings and they appear in some of the scenes in the movie as well when they talk about light and geometric forms.

art4d: Your works usually put more focus on landscape than built structures.

AW: You’re right. This film is different from others because of my obsession with the architecture and lighting of Bogota.

art4d: After Cannes, you went to the 32nd FID Marseille and they showed such incredible recognition for you and your work. I saw people carrying bags around with your name written in Thai. That must have been quite a memorable experience.

AW: It was very surreal. Imagine if there were people carrying bags with your name on them around the city. I’ve never looked at my name that way before. I used to wonder how people would react to it if they couldn’t understand what it was. To them, it could just be a meaningless drawing or a simple work of design. But it was surprising because I didn’t know about it before. When I arrived, I saw people carrying these bags. It’s such a prominent film festival in the southern region of France and people from other places including Paris usually attend.

art4d: The venue is interesting as well. It looks like a deserted building of some sort.

AW: That venue was used for the opening. It’s an outdoor theater. But normally, the screenings takes place at different local theaters. It’s the kind of festival that focuses on unorthodox, experimental films as well as documentaries. They’ve been screening my films throughout these past twenty years. This year, they gave me the Grand Prix d’Honneur, which is kind of like an honorary award. It was incredibly surreal and dream-like, from Cannes to the bags and to this.

art4d: How do separate your life as an artist and filmmaker?

AW: It’s all mixed up. The process of filmmaking is the opposite of art in the sense that it doesn’t generate income. The period when I work on a film may take a year, and during that year, I may have people who would come buy me meals when I’m on location. But one thing reflects the other, in a way. It’s still pretty confusing to me. I don’t have a specific formula and everything sort of flows together. Sometimes I incorporate both things together. The performance I did at Fever Room (Japan) originates from Cemetery of Splendor. Memoria also has some sort of succeeding connection. It’s like one form feeds on the other.

art4d: And now we have ‘A Minor History,’ how did that come to be? What story do you intend to tell with this exhibition?

AW: I was wrapping up the making of Memoria and I hadn’t been in Thailand at all. But there has been such a tremendous political movement going on and it’s inescapable now. I decided to go back to the route I’ve taken, which is making art. To me, making art is like having a meal. It’s nutrients I feed my brain with. With each work, I take a considerable amount of time researching, but I don’t think of it as a job. I look at it as something that fulfills what was stolen from me when I was kid, a chance to learn about things in elementary and secondary school. I was in the area but I didn’t know anything that happened at the time since the Primitive project. It intensified my passion for travelling as well. I took the same route, along Mae Khong River, from Nong Khai, Nakhon Panom, Mukdaharn to Ubon Ratchathani. I want people who have seen the exhibition to do the same. Travel, in Thailand, on the route you love and take your time. Each year, you can see the changes that have taken place. With this project, I intend to talk with the young generation, especially in Khon Kaen where I grew up. Young people operate differently from how people in my generation used to. They don’t care about seniority or believe in systems they are told to believe in anymore. Meanwhile, I’ve seen how the environment has changed. It’s the first time for me to see Mae Khong River in this color. It’s blue now. It used to be this earthy, muddy color. Since ‘For Tomorrow For Tonight,’ I’ve known and witnessed how China and Lao’s dam construction at different water sources have created devastating impacts, but I’m not an activist. I only went there to film, and to document. The project is divided into two parts. The first part emphasizes on traces, from dead bodies to deteriorated structures of old movie theaters, whatever I came across during the journey, including the traces of Mae Khong River that will never go back to the way it used to be. I could really feel that. Then, there are political memories of the area. The second part will focus more on young people and citizens.

art4d: Why have you designed the installation into three different screens with a Mor Lam set in the middle?

AW: It’s a kind of beauty that is somewhat more special than film. It’s a layer within a dimension and offers freedom for viewers to choose which screen they want to look at or observe and notice the relationships between the screens, which feel very much like these abrupt thoughts that pop up in your head. Mor Lam is something I grew up with. I grew up listening to the radio, watching movies in a cinema as well as watching Mor Lam artists perform. I knew Bank, the Mor Lam artist, because I used to work with him and this footage was captured while he was working. You can see the storytelling of these mundane places; a palace, a shack at the end of a rice field, a forest. There are only a few settings but we filmed them without any actors, just empty sets. It’s like watching the spaces communicate; the souls being joined to this hybrid show.

art4d: Are you still working with your favorite sound mixer with this project?

AW: Yes. I have been working with Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr (Rit) for 15 to 20 years now and it’s like we’ve found each other’s tunes. He knows which sounds or ranges that I like. Since the release of Memoria, 100 out of 100 viewers will say that this film is about sound design. So with this project I gave him a lot of freedom to experiment on different things.

art4d: And there’s also Mek Khrungfah.

AW: He’s from a younger generation and he’s an activist as well as a teacher. He is a poet and his work captivates me. He talks about experiences and his own political awakening, just like how I’m watching Mae Khong River dying. These kids are emerging. They are the new sounds; the new voices, and they’re intense and aggressive. Mek is like this beautiful and aggressive voice; the kind of voice that is completely aware of what it wants for the life that the government and society has failed to give.

Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai, ©100 Tonson Foundation, 2021

art4d: I read somewhere that you meditate. What’s the starting point of that, could you tell us a bit about it?

AW: I do practice meditation. It’s the madness inside my brain. I’m an over-thinker. I think it started after my father died in 2002 and I was about to start working on Tropical Malady. I was very mad and felt like I was on edge all the time. The years between 2005 and 2007 were quite a transitional time for me. I tried studying Buddhism and it’s very scientific, having to meditate and contemplate with the mind. I think it relates to what I do as well. Art and film is about time, and self—who I am. And meditation helps me with that.

art4d: I remember you mentioning the awareness of now.

AW: That’s right. It was like I created this whole other world and saw it as the most beautiful piece I could get from life. It’s like understanding how to live in the present, which was so hard for me back then. It’s still hard now. Making a film or an installation can get me to that point in a way. When I design something for people to perceive and digest, the most important thing is to listen. It isn’t just about the plot, but sitting down and listening to what happens.

art4d: Is it possible that you may want to try to simulate those inner feelings through a sensation in the body, kind of like how an inner experience connects to the act of meditating?

AW: That is possible. In many scenes, that’s how I want to convey the feelings but I can never do that with films. It’s merely a simulated state.

art4d: I read one of your interviews with an international media outlet, and you said that one of the activities you like doing during lockdown is watching trees.

AW: During lockdown, the projects that I was supposed to be working on came to a halt or were postponed. But I know that I’m still a lot luckier than a lot of people. I think people need to learn to stop. To me, this period of time is valuable in the sense that I get to look at where I’m at in life. Even with the energy I have with the house, I’ve never really looked at and experienced that before despite the fact that it’s something that I built. And I’ve learned a lot from that, especially from the animals. I looked at my dog and I saw him just sitting there, looking around and sometimes he would just fall asleep. If I could just learn what he feels, that would be nice. To be able to look at the things around you is very valuable. When you don’t have to do anything, take it as a chance for you to look at what surrounds you. Before COVID, all I could think about was the future.

art4d: You used to do an online forum with Thai Film Archive and I remember you mentioning your interest in Japanese literature and that you were reading Mishima Yukio’s books. What is it about Mishima’s work you find to be appealing?

AW: The way they talk about the complexity of human lives is so riveting, from sexual desires, power hunger and how we are all swept away by the stream of these endless needs. All of Mishima’s novels, despite being set in Japan, reflect these issues. Watching these people live their lives; it’s like meditating in a way. When I did that interview, I was reading his last four works and they talk about a man’s reincarnation, from one to four lives.

Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai, ©100 Tonson Foundation, 2021

art4d: What are the three most important things in your life right now?

AW: That’s…tough. (we talked about other topics for a while as Joe tried not to say it’s filmmaking because it’s quite dangerous to hold on to the role of a filmmaker). The first thing is the life I’m living. I’m living with my sibling and a dog and that’s enough. I don’t have to try too hard. Then it’s continuing to help Tong with what he has done. So it’s Tong. That keeps my hands full already. The second thing is seeing. Losing the ability to see is what I fear the most. The last is probably trees. I try to grow at least three new trees at home within the span of a year. If I can grow five or ten trees, I’ll be glad.

art4d: And your plan after this?

AW: I’m writing a new screenplay and it should be a project that I’ll get to work with Tilda again. I can’t say much about it right now but it’s very special. You can say it’s a new platform. And then I have another performance piece in Japan and South Korea.

art4d: How do you want to see Thailand progress from now?

AW: Wow…Can I wish for what the kids are hoping for? I want to see a reform. That’s it. I want the military out of politics. That’s very important. The military needs to leave the stage and reform itself. I want the monarchy to reform. That’s all I’m asking and everything will follow from there.

Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai, ©100 Tonson Foundation, 2021

Part One of ‘A Minor History’ is now available for viewing at 100 Tonson Foundation until November 14th, 2021, while Part Two is set to take place between November 25th, 2021 and February 27th, 2022.