IN RECOGNITION OF THE EUROPEAN AND WORLD DAY AGAINST DEATH PENALTY, OCTOBER 10, THE EU DELEGATION TO THAILAND INVITES US TO WATCH A NEW DOCUMENTARY “HAKAMADA” SHOWING HOW A FAULTED JUSTICE SYSTEM HAD PUT IWAO HAKAMADA IN PRISON FOR 47 YEARS, 33 OF WHICH ON DEATH ROW

TEXT: PAWIT MAHASARINAND

PHOTO: COURTESY OF DELEGATION OF THE EUROPEAN UNION TO THAILAND

(For Thai, press here)

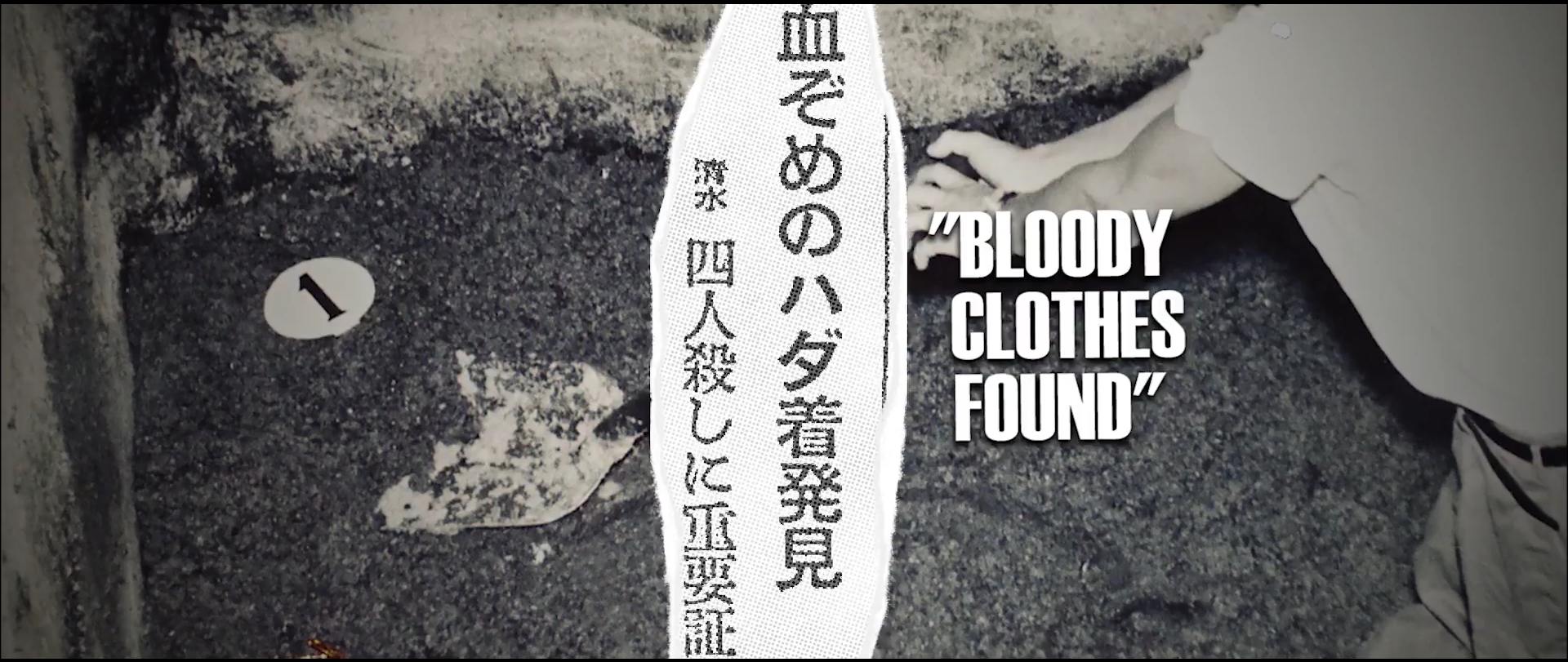

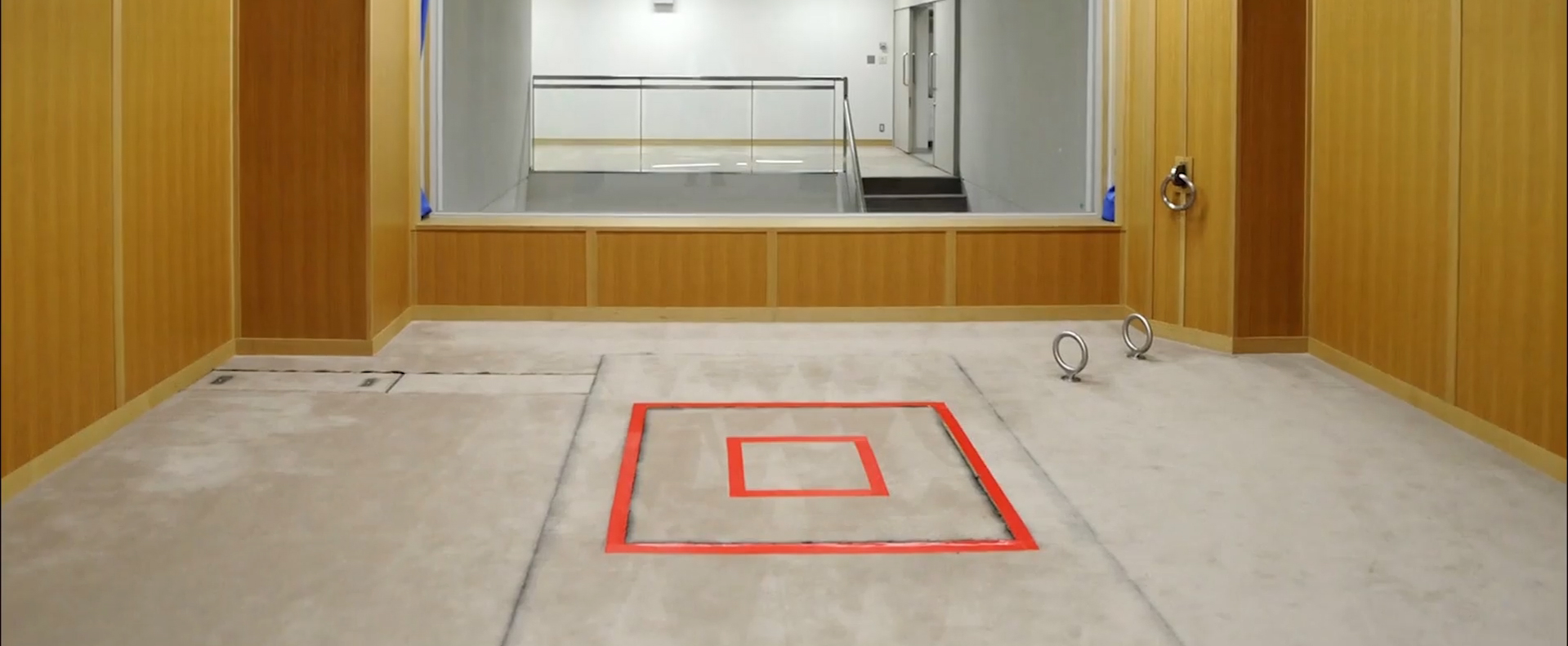

The opening scene of Melbourne-based director Louis Dai’s documentary “Hakamada” (2019) has long shots of familiar metropolitans of the country universally known for discipline and serenity with a voice-over of a Japanese man, calmly yet harrowingly, describing mornings of the executions during which the death row inmates heard the prison guards’ footsteps approaching until they stopped at a certain cell. As the fond memories of such contemporary Hollywood films as “Dead Man Walking” (1995) and “The Green Mile” (1999) surface, the film’s title then fades in. We naturally assume it’s the voice of former professional boxer Iwao Hakamada, Guinness World Records’ “longest-held death row inmate”; we later find out that it’s not. “Hakamada” is not just about a man who was doubtfully convicted for quadruple murder, robbery and arson in Hamamatsu, a quiet small town in Shizuoka prefecture in central Japan, back in 1966.

In the 72 compelling minutes of this documentary, the audience learn about the timeline of this case through a questionable justice system which seems to pronounce the guilty verdict first and then find proofs to support it later. It not only allows a crime suspect to be put into custody for more than three weeks for interrogation without a defense lawyer’s presence, but also denies the defense team access to the related evidences gathered by the police and the prosecution team. With the tightly knitted relationship between judges and prosecutors, Japan’s high conviction rate is not surprising; what’s astonishing is that it’s as high as that of China’s.

Dai himself was an expatriate, outsider who speak very little Japanese, when he first became interested in this case as the public outcry for Hakamada’s release and retrial was intensifying; as a result, his well-paced narrative in this film suits many of us outside the country who have not either closely followed the case or known about it. Although Dai tries to be neutral by not applying standards from other countries, the film would have been less one-sided had the police and the prosecution team had more presence. Exceptions are a few sound bites of the former’s inhumane interrogation in which toilet breaks were not allowed and the then-retired judge who handed Hakamada the death sentence regretting it in tears after his decades-long silence.

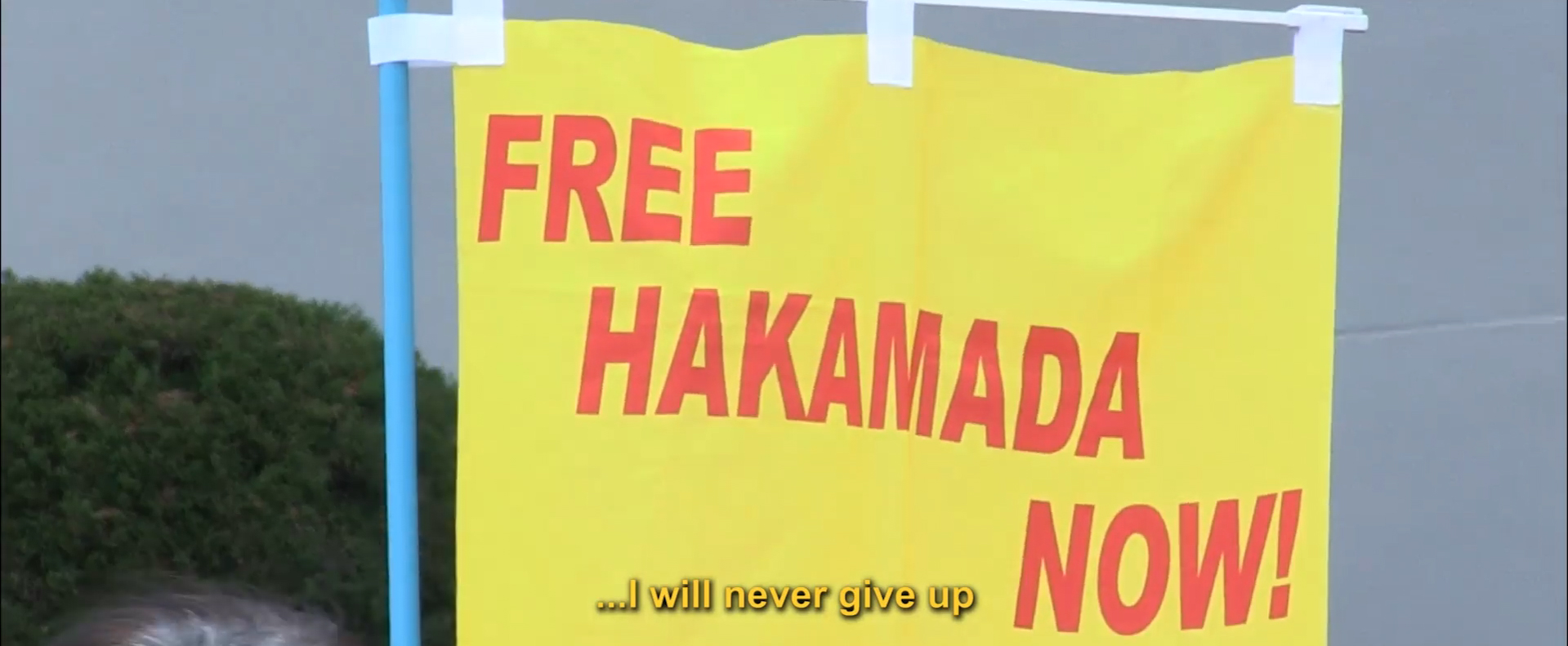

We don’t see Hakamada in his long incarceration but hear about his psychologically deteriorating condition from his elder sister Hideko who, with strong belief in his innocence, has devoted half a century to fight for his justice, first by herself and later with help from, among others, Amnesty International Japan. When we see Hakamada being released from the Tokyo Detention Center and later hear him speak while walking back and forth in his sister’s home, her words come back, triggering our imagination on what it’s been like in the solitary confinement. Shortly afterwards, and soon after we think that the long-overdue justice is served, we’re reminded that it’s not yet a victory to be celebrated. The case is still at the supreme court, after the lower court’s disapproval for retrial, and we never know whether Hakamada, now 84, would be able to clear his name in life or posthumously, or he would receive any compensation.

Back here in the Land of Smiles, the last execution of prisoner was in 2018, after the absence of nine years. It seems that whenever there’s a rape or mass murder case here in a primarily Buddhist country, we restart our debate on this an-eye-for-an-eye-a-tooth-for-a-tooth-a-life-for-a-life issue, citing various reasons. Let the discussion continue notwithstanding the cold hard facts that most countries have already abolished the capital punishment and that the word “corrections” in the name of the responsible government agency suggests punishment and reformation rather than revenge and termination.’

It’s thus timely that we’ll get to watch “Hakamada” on the European and World Day Against Death Penalty (October 10), thanks to the collaboration of the EU Delegation to Thailand, Alliance Française Bangkok and Documentary Club. It’s even more timely now that Thailand’s justice system is in more jeopardy than ever, for both the hit-and-run-then-travel-the-world case and frequent charges on political activists, we’ll also be listening to and discussing with the panelists from different fields after the film. “The Death Penalty: Justice or Capital Mistake?” panel discussion (in Thai with simultaneous English translation) features Namtaee Meeboonsalang, a provincial chief public prosecutor; Piyanut Kotsan, director of Amnesty International Thailand; Phra Theppariyattimuni Tuwanno, abbot of Hong Watthanaram temple; Don Linder, screenwriter of Thai film “The Last Executioner”; and Sanhawan Srisod, a legal advisor of International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

For more details, visit Facebook: European Union in Thailand.