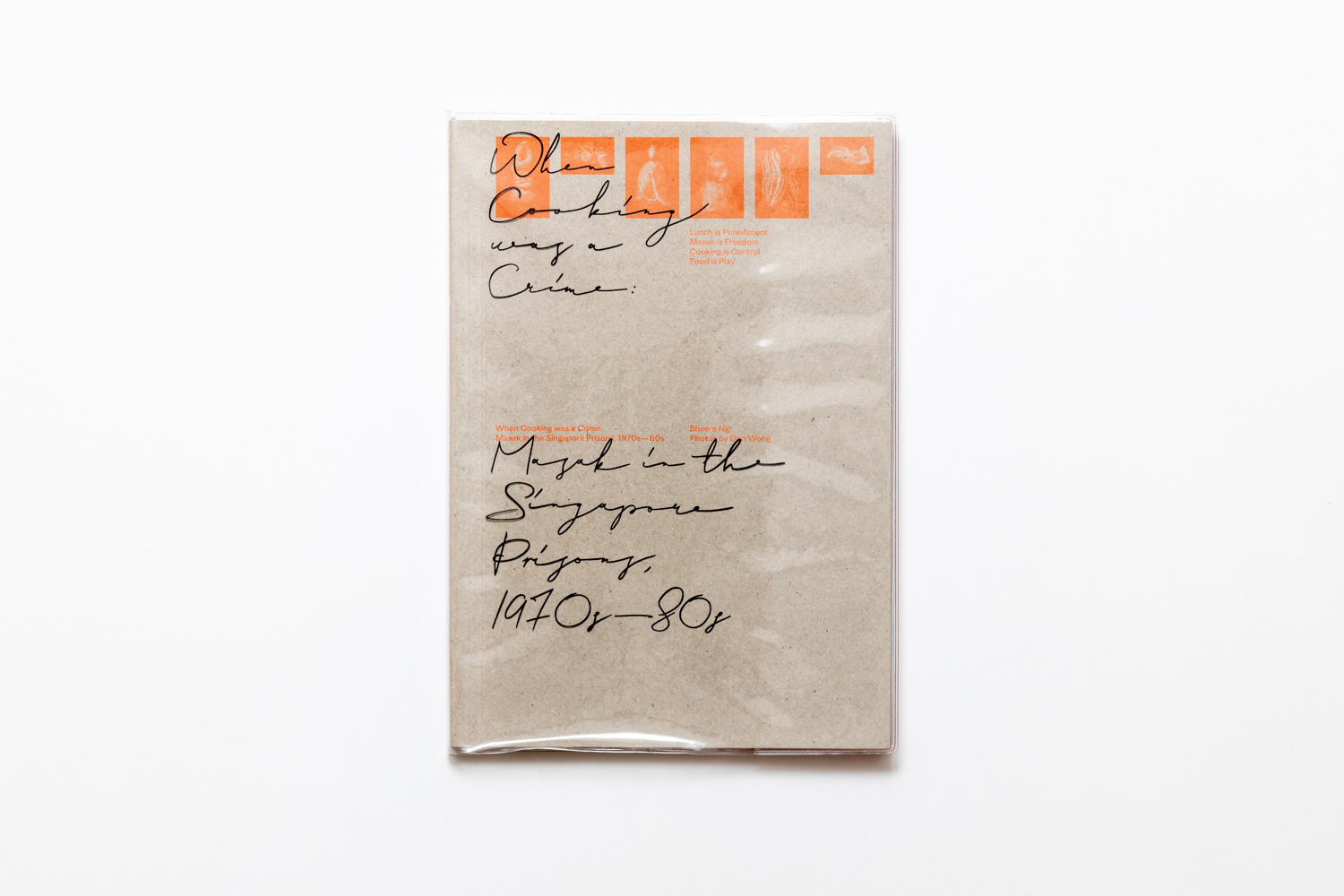

RELIVE THE MEMORIES BEHIND THE KITCHENS OF PRISONERS IN SINGAPORE DURING THE 1970S – 1980S WITH THIS PHOTO BOOK THAT PORTRAYS THE MASAK OR THE PRISONER’S SECRET KITCHEN SMUGGLING OPERATION THROUGH THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF FOOD AND KITCHEN UTENSILS WHICH CELEBRATE THE FREEDOM (OF TASTE) OF THOSE WHO ARE NOT FREE

TEXT: PRATARN TEERATADA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

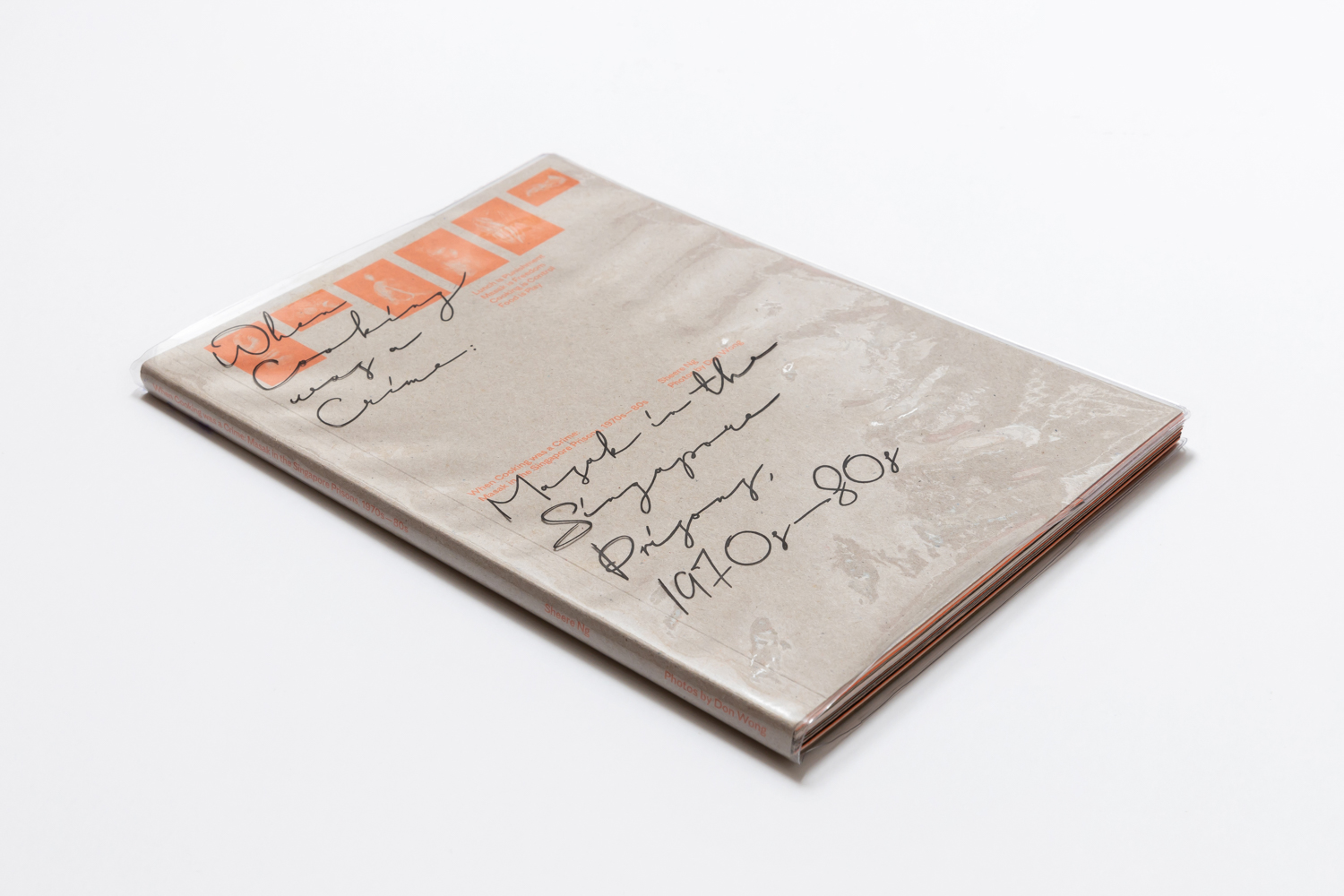

Research and Text by Sheere Ng

In Plain Words, 2020

176 x 250 x 10 mm

128 pages

Soft cover with plastic sleeves

ISBN 978-9-811-48239-7

There is one fact about good creative works: they tend to be born out of the creators’ predicaments and struggles as they are forced to go through and overcome more challenging and painful obstacles than people with a comfortable lifestyle would have to. Think of the early songs by bands like Carabao or Oasis when they were still poor and unsuccessful, or the low-budget films Zhang Yimou created during his days as a young, unknown filmmaker, or Van Goh’s paintings.

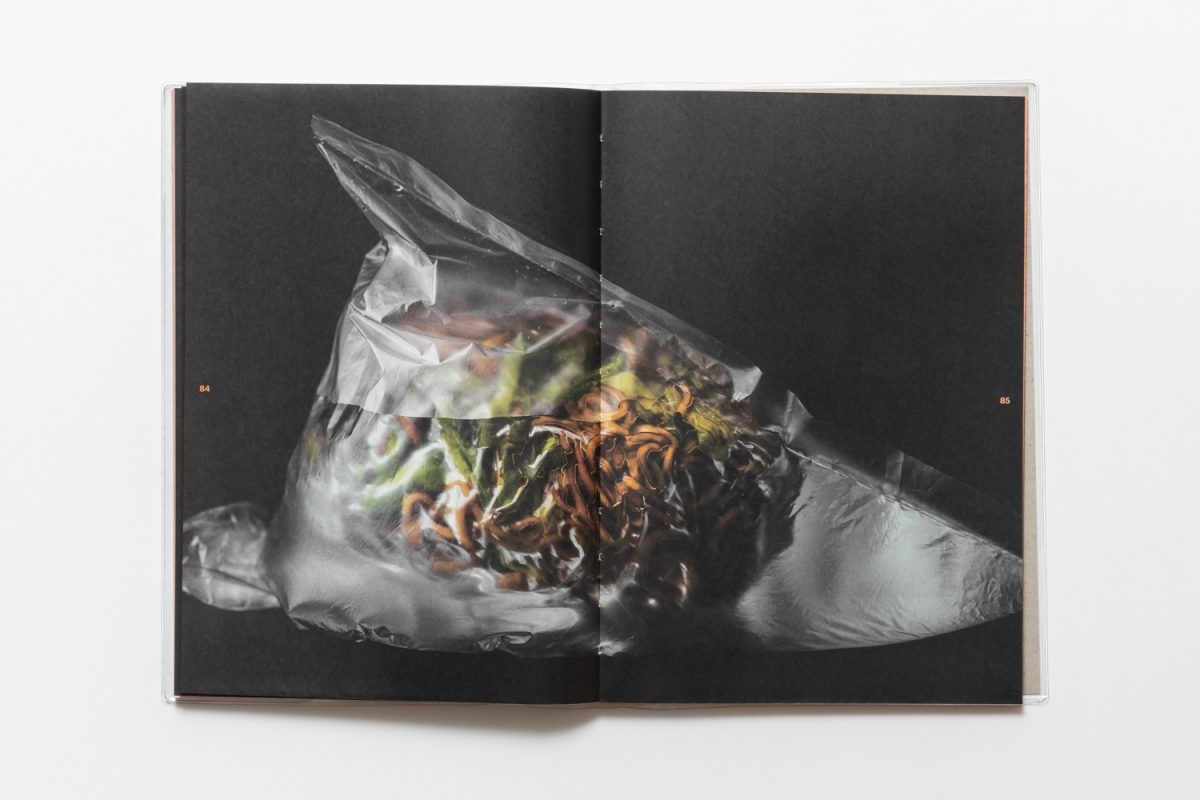

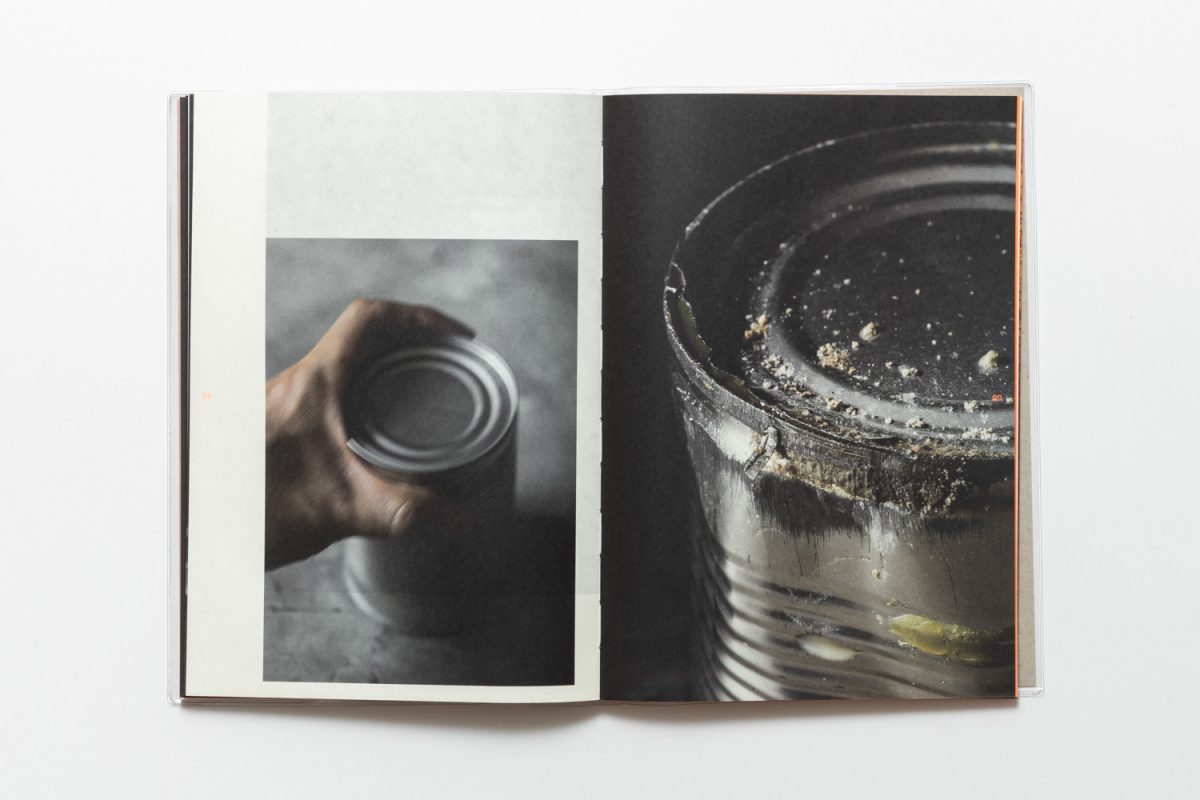

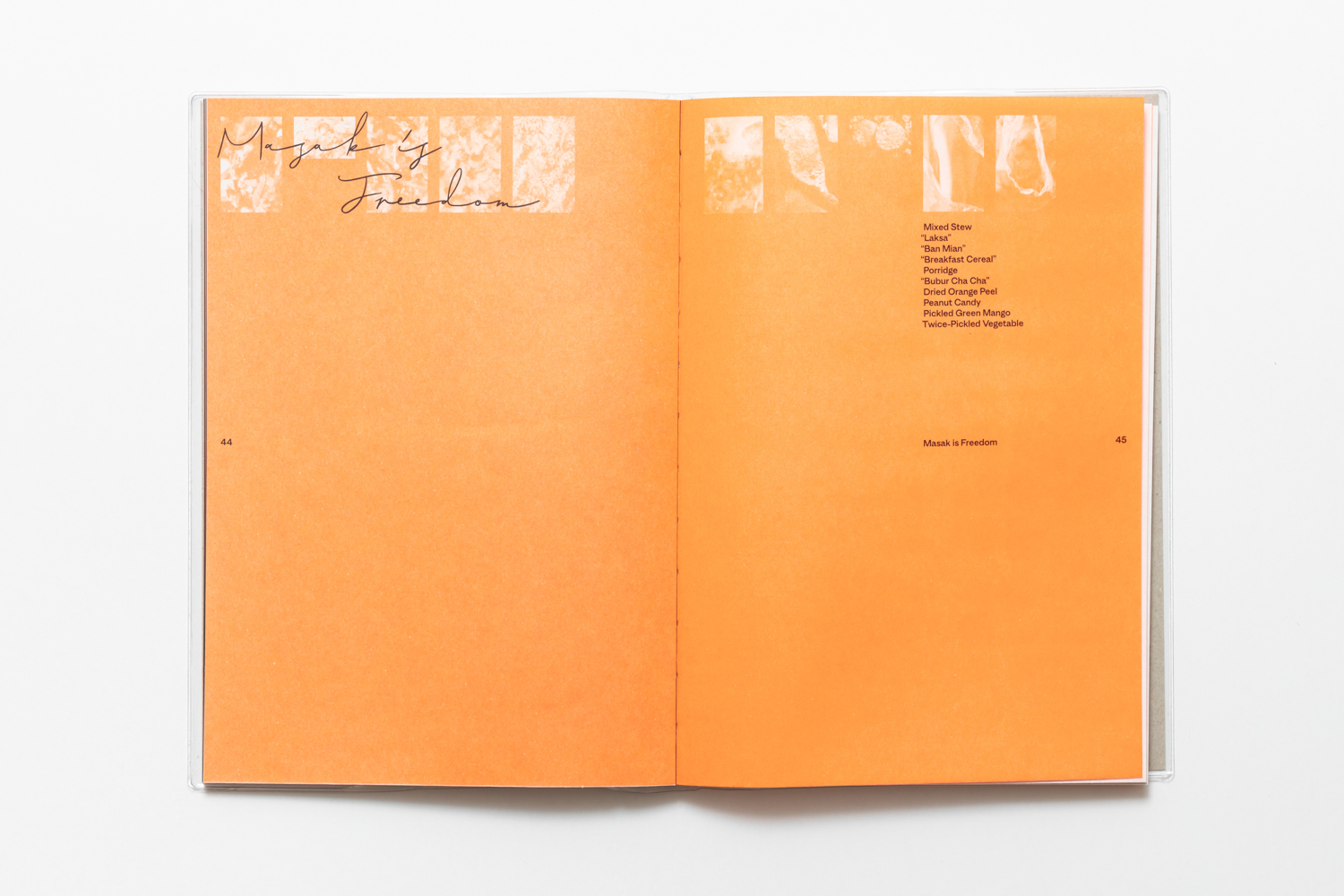

This book combines experiences and memories of prisoners incarcerated in Singapore’s prisons between the 1970s – 1980s about operation MASAK or the kitchen smuggling operation. Most of these prisoners went to prison for drug-related crimes and their association with criminal organizations. In Asian culture, food is a symbol of love. In the time when the society was peaceful and the economy prospered, as a prisoner, finding your way to snatch goods and ingredients and making secret appointments to cook with your fellow inmates behind the guards’ back was undoubtedly a celebration of freedom.

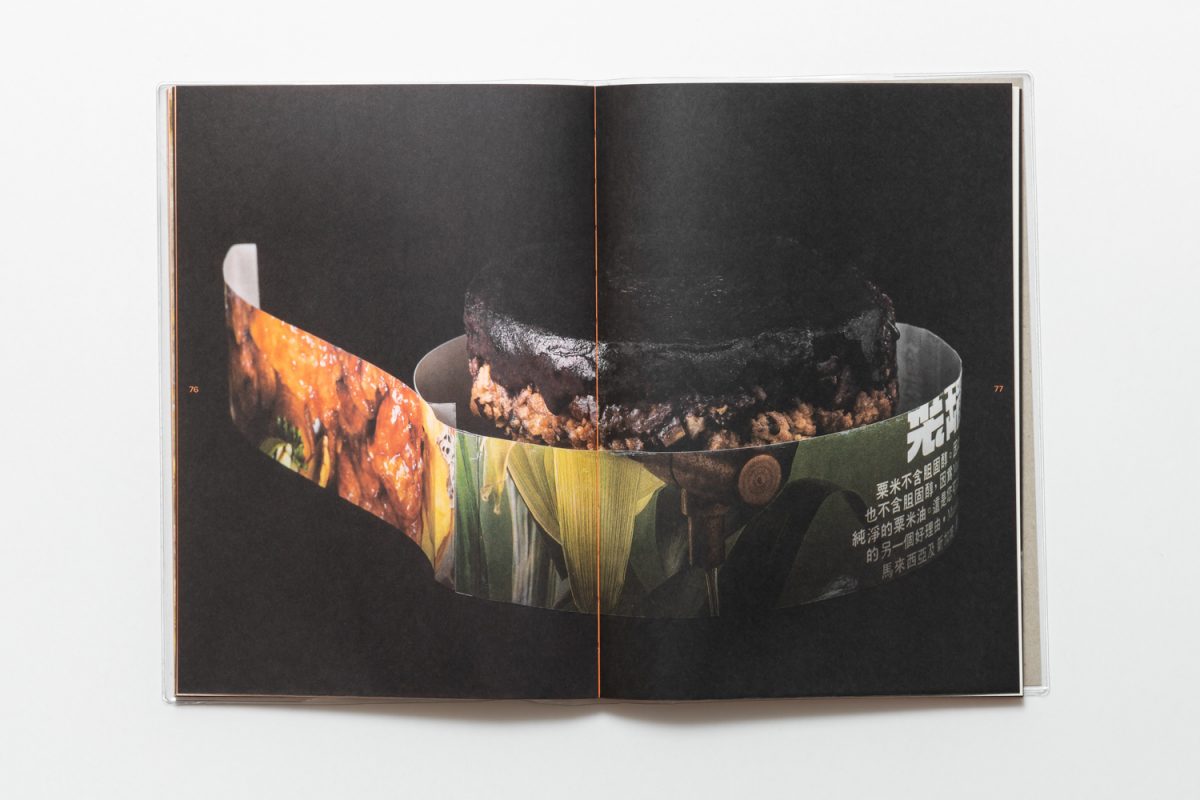

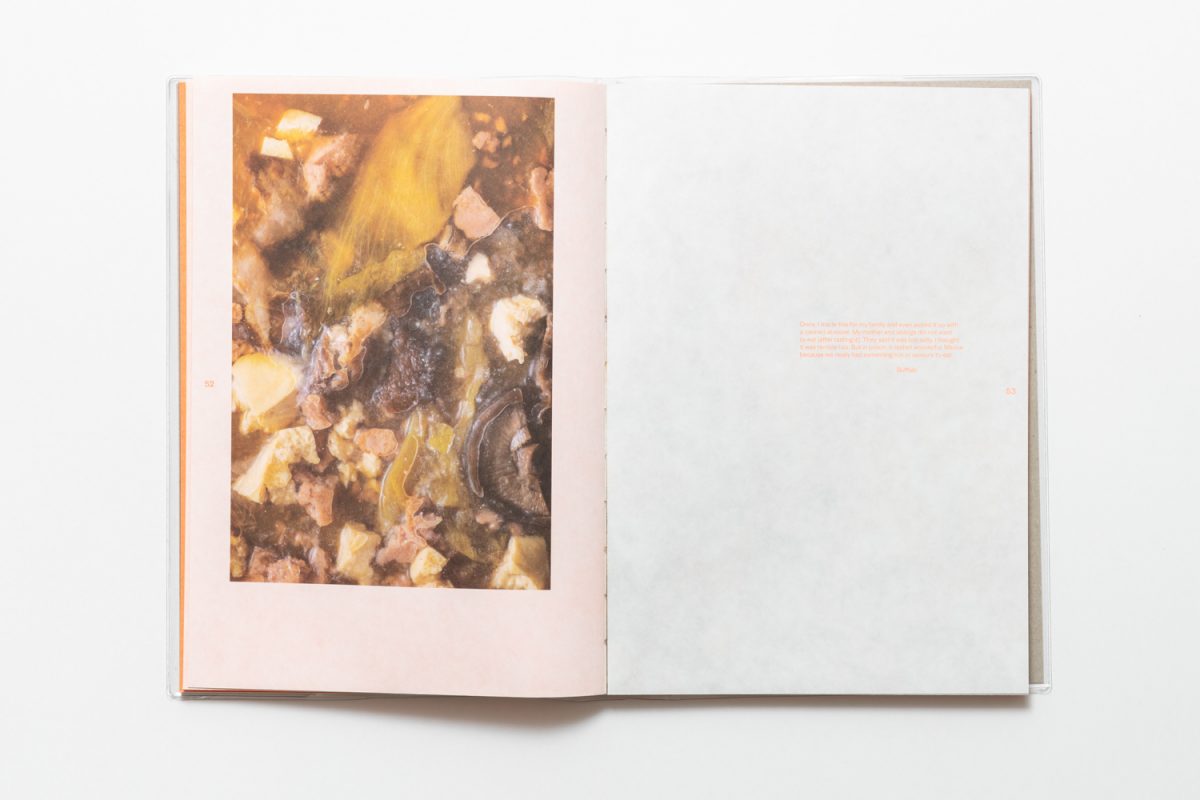

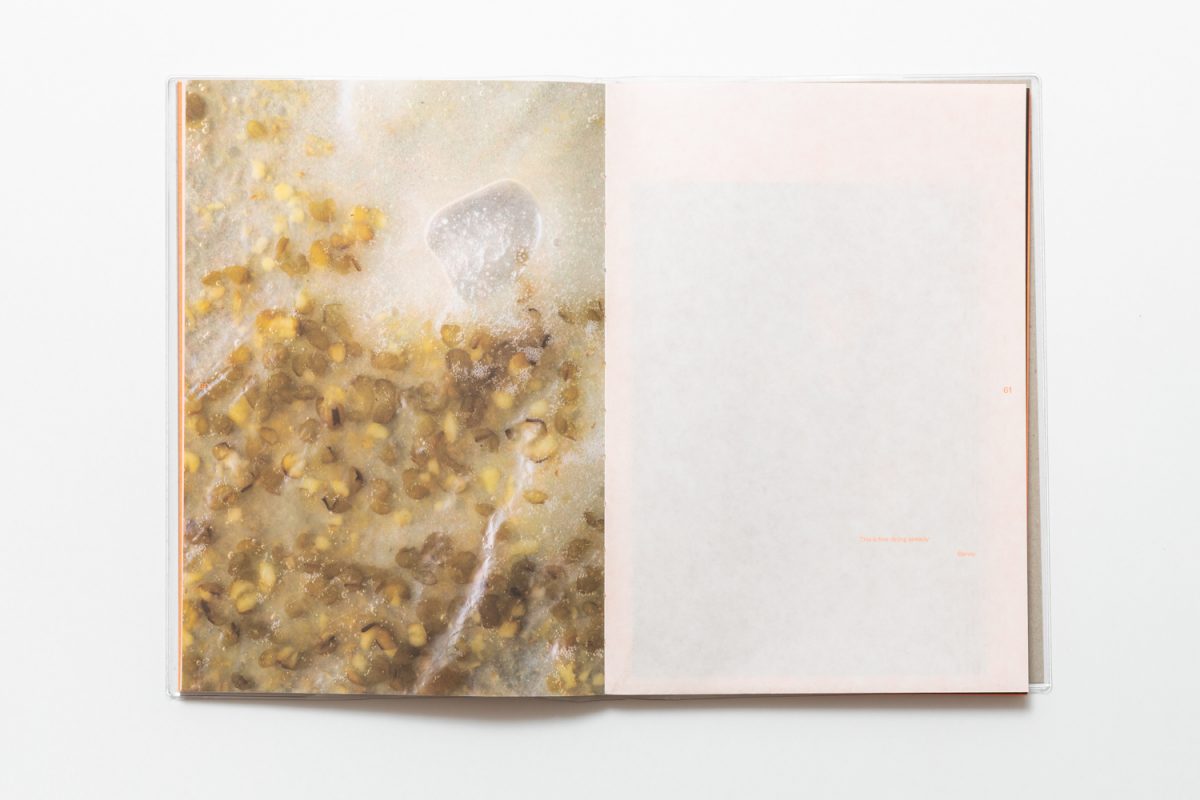

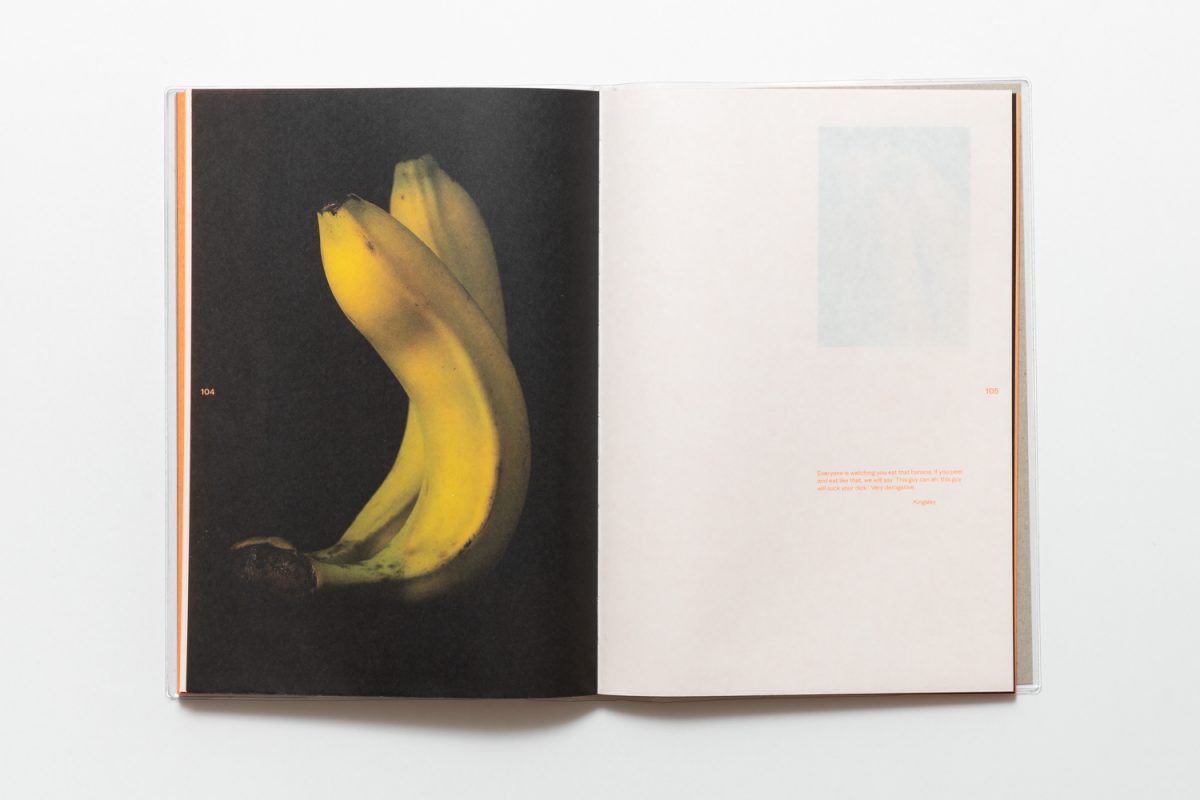

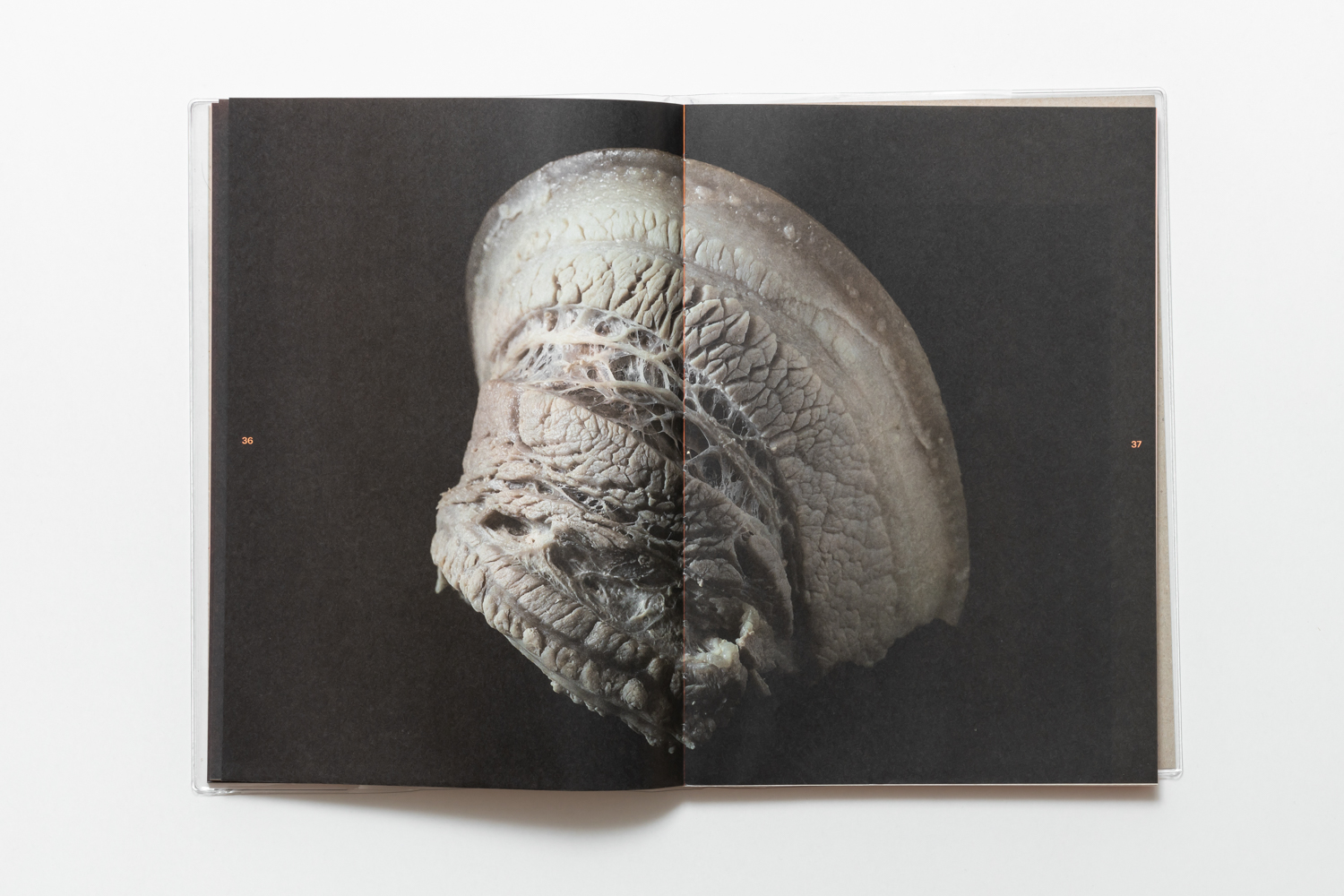

While life in prison guaranteed three meals a day, for most prisoners, having to eat cold, tasteless food on repeat was another form of torturous punishment. The MASAK operation, in a way, signified rebellion through stealing and possession of contraband objects, destroying the state’s property, all to make local dishes they were craving. They mixed and matched whatever ingredients they could find from the kitchen to the hospital room and training rooms during the day. In a way, it was a declaration of freedom—the hot, flavourful food cooked in the flavors that could never be found in prison food. The cooks’ ability went through the roof when they managed to make birthday cakes, play food games and to even have used food to create sexual metaphors.

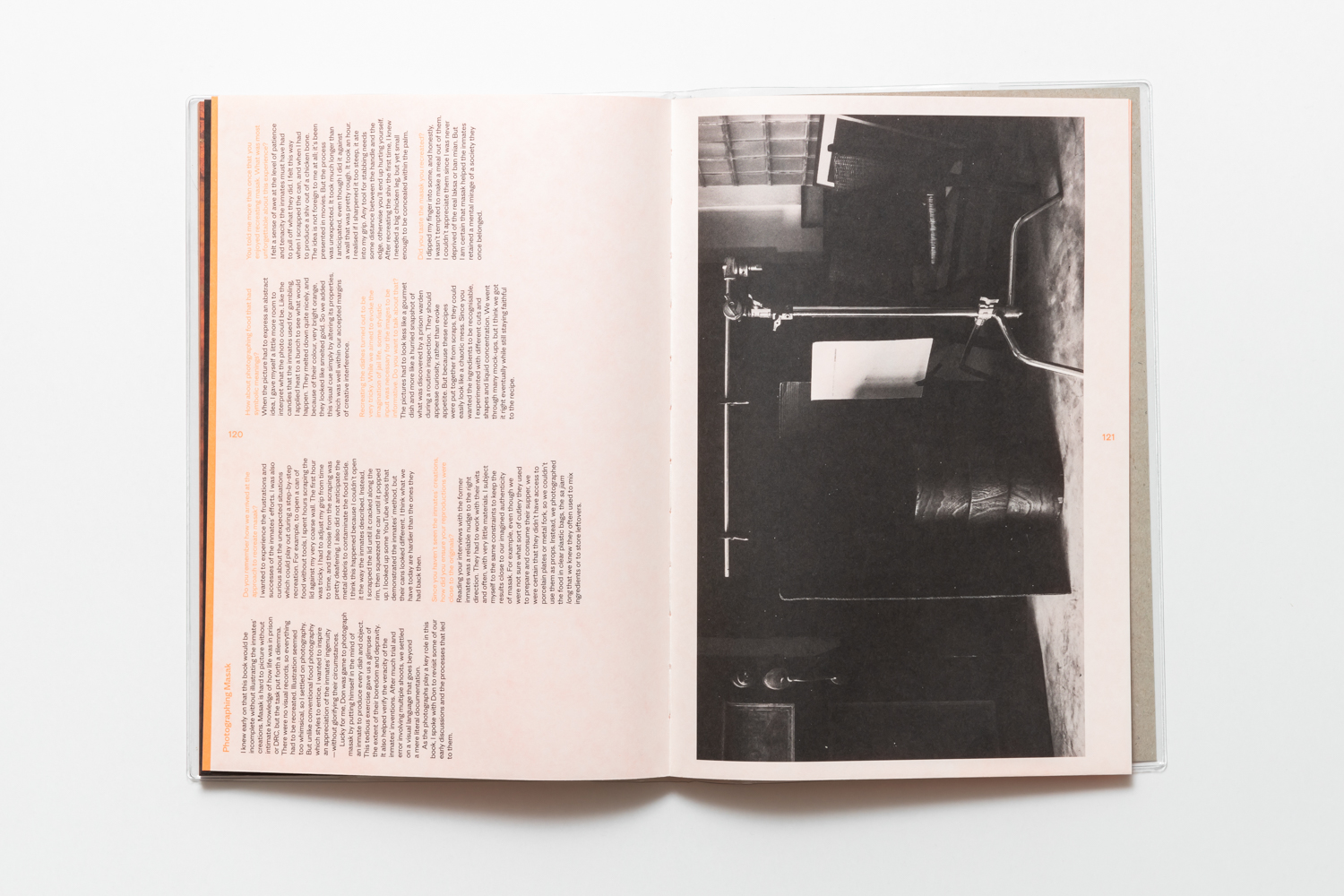

The team behind the making of the books includes Sheere Ng, a writer and researcher with an eager interest in food and marginalized cultures. Ng went from place to place to interview former inmates who were incarcerated during the particular time, reproduced the conversations, and transformed them into photography by Don Wong with Practice Theory overseeing the book’s design. The final result is a book with photographic recreations of dishes and cooking utensils from the memories and stories of the prisoners in Singaporean prison during the 1970s and 1980s. It was a period in many people’s lives filled with friendship, creativity, and a longing for freedom.