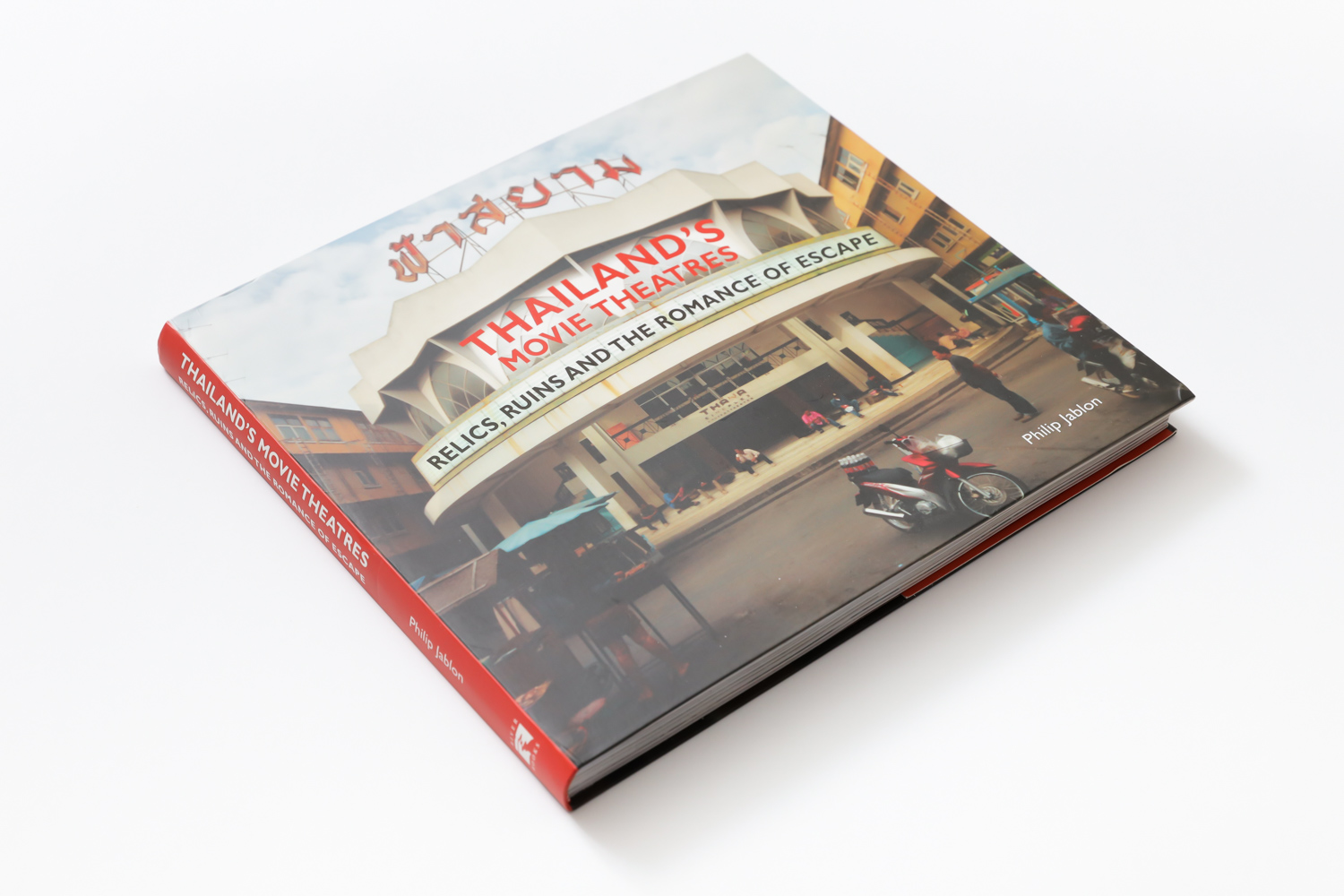

TO REMIND OF HOW MUCH IT MEANT IN THE PAST TO COMMUNITIES AND PEOPLE AND BRING BACK THE GOLDEN AGE OF THAILAND STANDALONE CINEMA, PHILIP JABLON, AN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHER, SPENT MORE THAN 10 YEARS COLLECTING THE FINAL MEMOIRS OF THE STANDALONE MOVIE THEATERS THROUGH HIS PHOTO BOOK

TEXT: PRATARN TEERATADA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

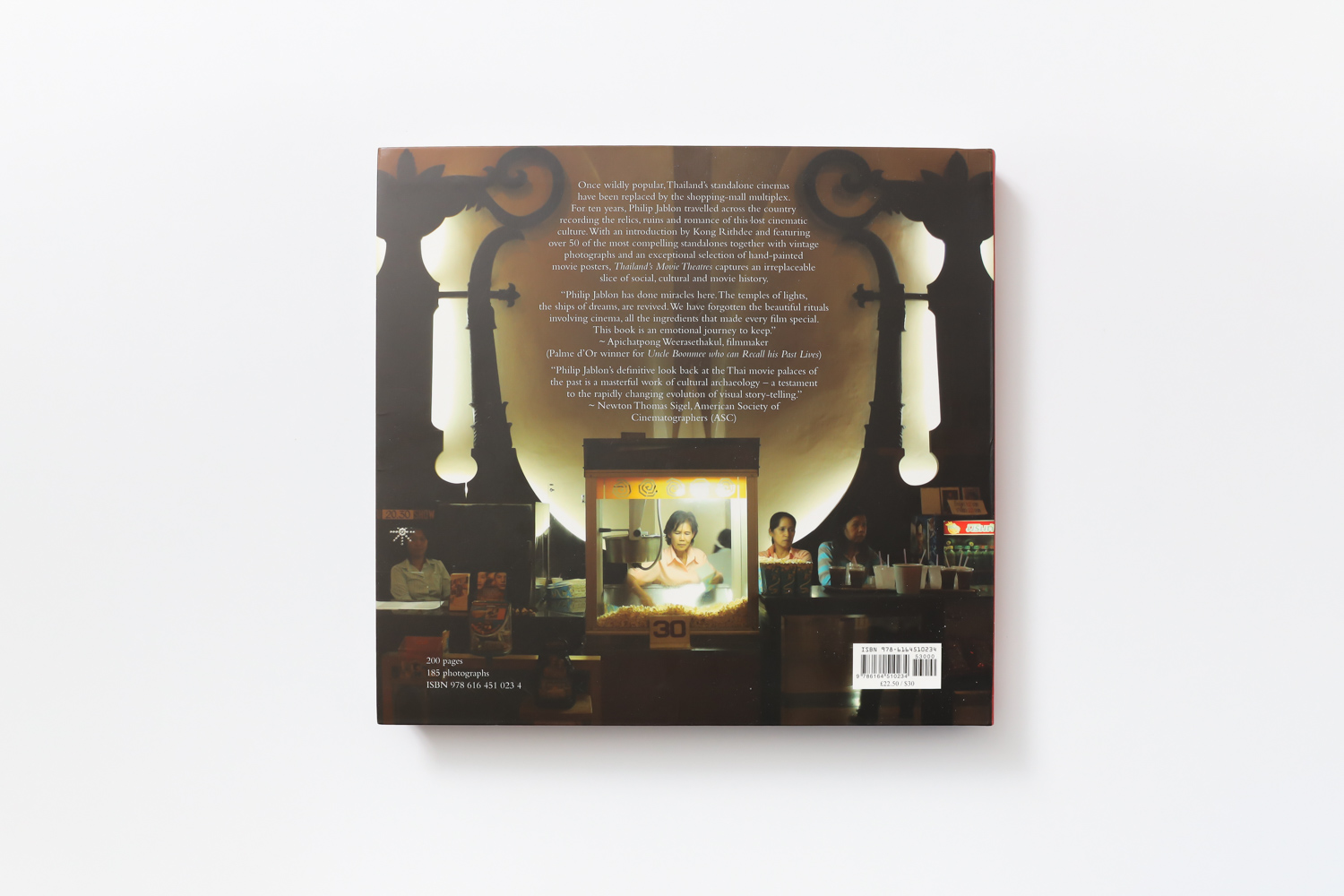

Philip Jablon

River Books, 2019

9.33 x 0.8 x 10.07 inches

Paperback

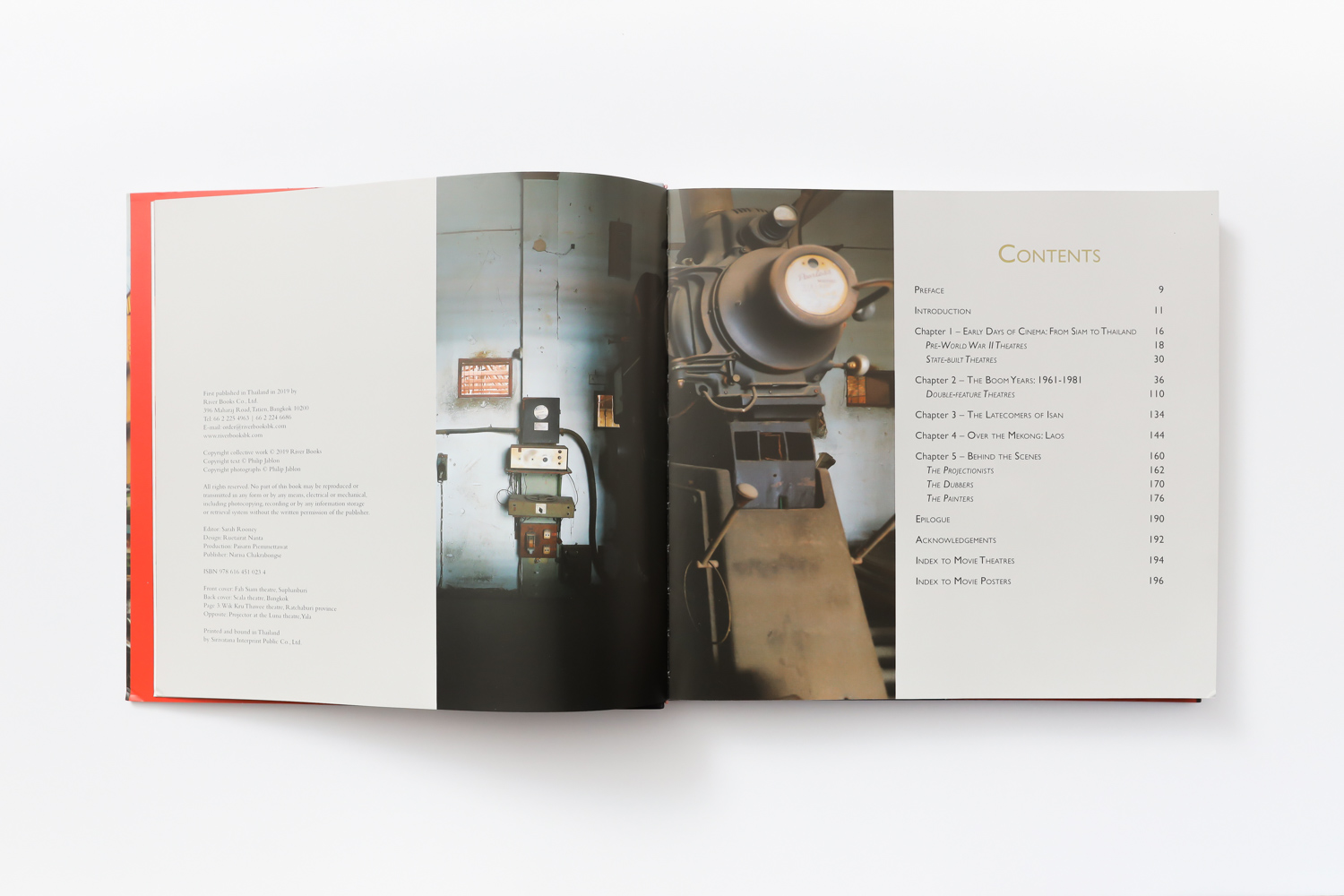

208 pages

978-6-164-51023-4

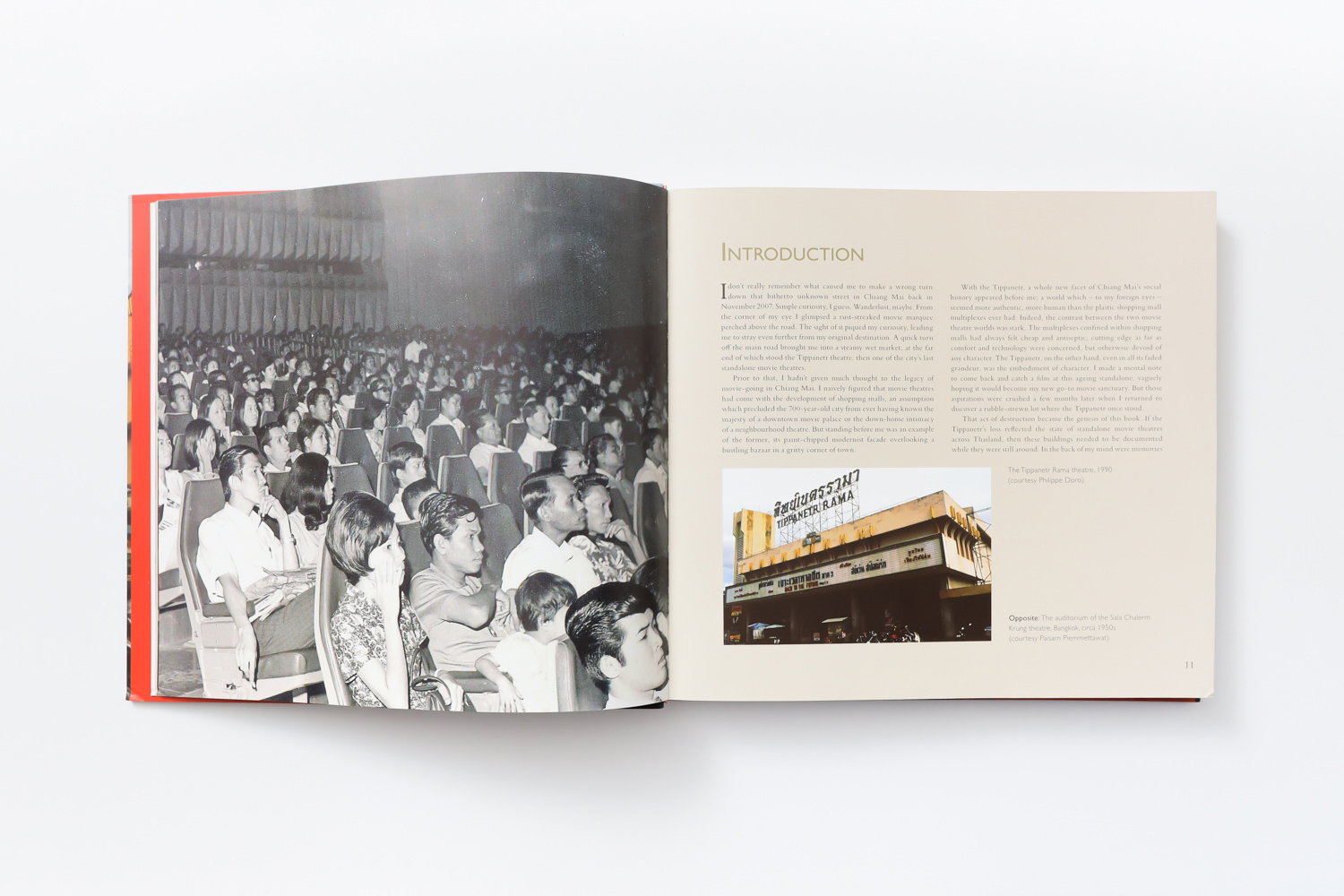

I finally had a chance to watch Tsai Ming-Liang’s ‘Goodbye Dragon Inn’ last year. The Taiwanese film tells the story of a time before an old movie theater named Dragon Inn was about to close down. As expected from the Taiwanese director’s cinematic language, the film is filled with stillness, an unhurried pace, languidness and very little conversations. They, however, fit well with the film’s settings, which are merely the inside and outside of the movie theater, showcasing a few cinema goers, the usher doing all kinds of work, and the projectionist operating the screening room. It’s a sense of being entirely disconnected from the outside world. It’s the spirit, the wreckage and the kind of romance that cannot be found anywhere else but inside that particular theater.

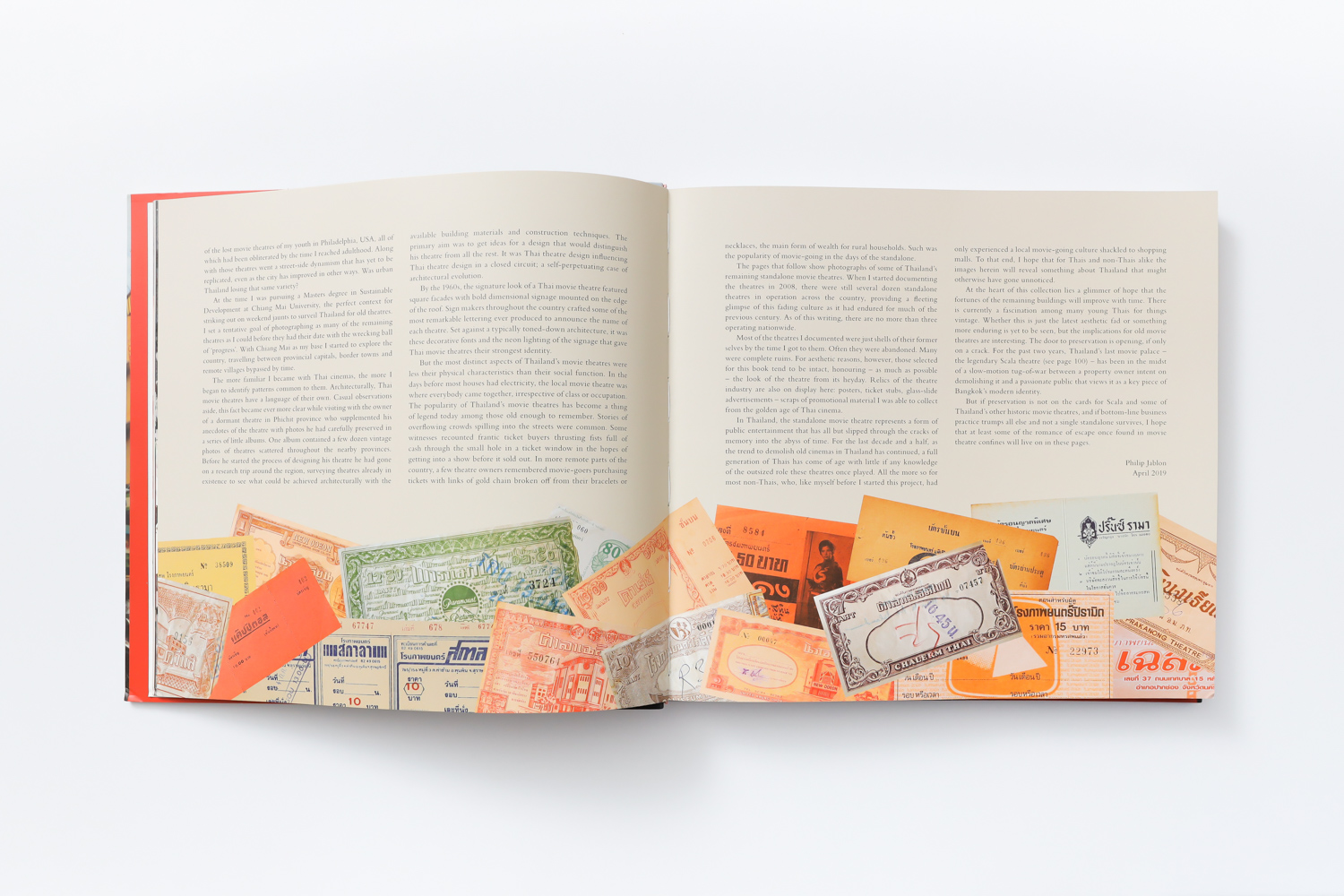

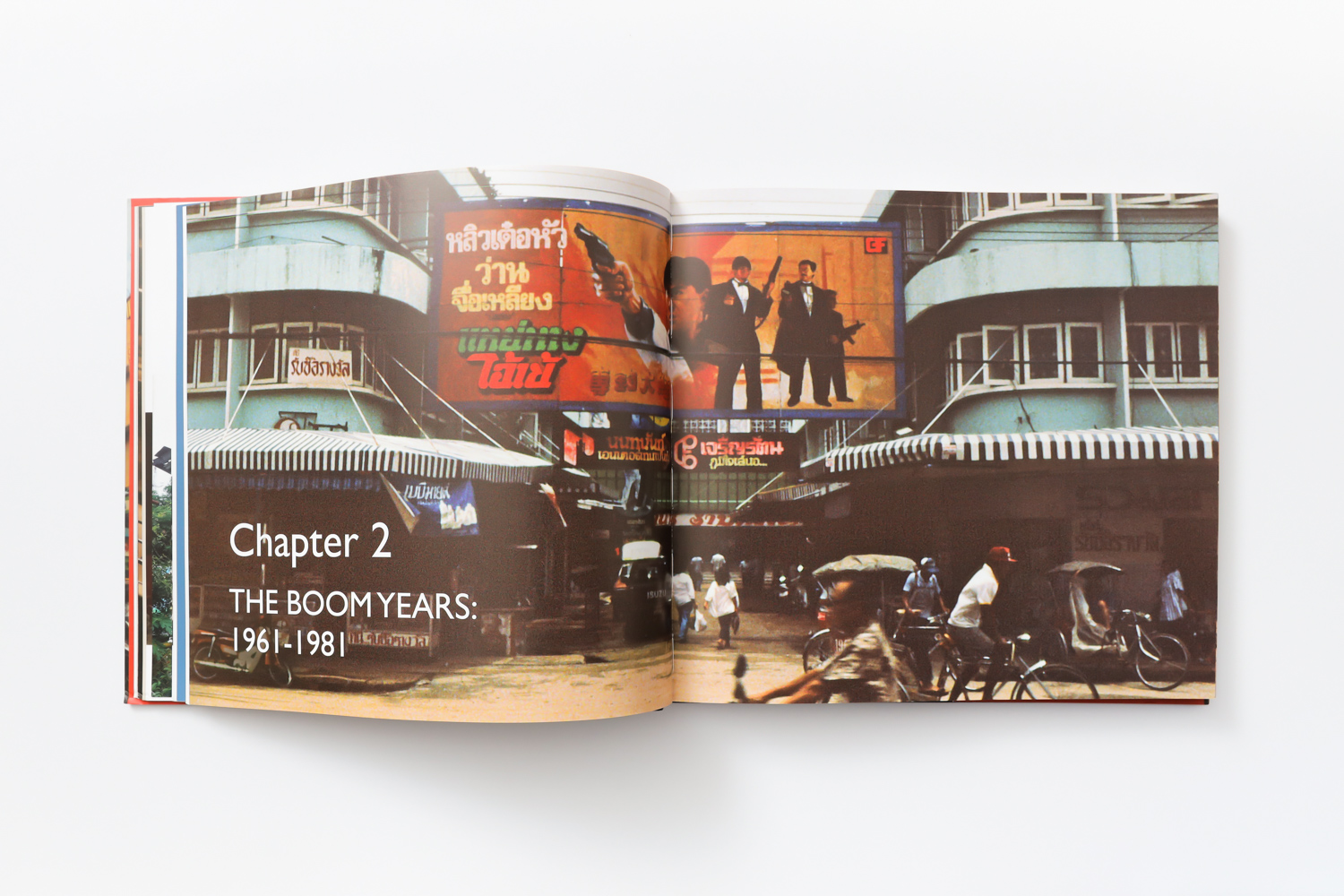

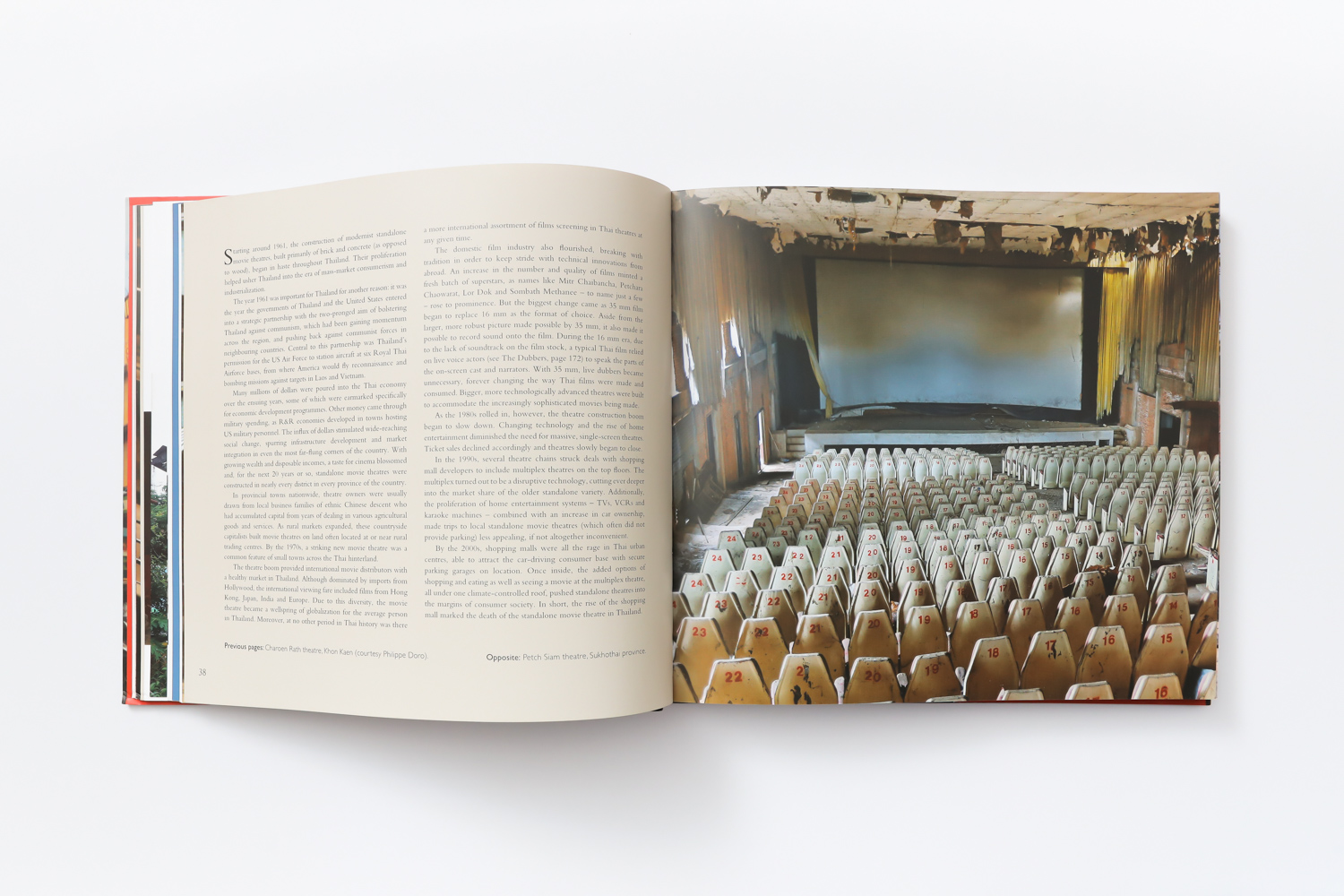

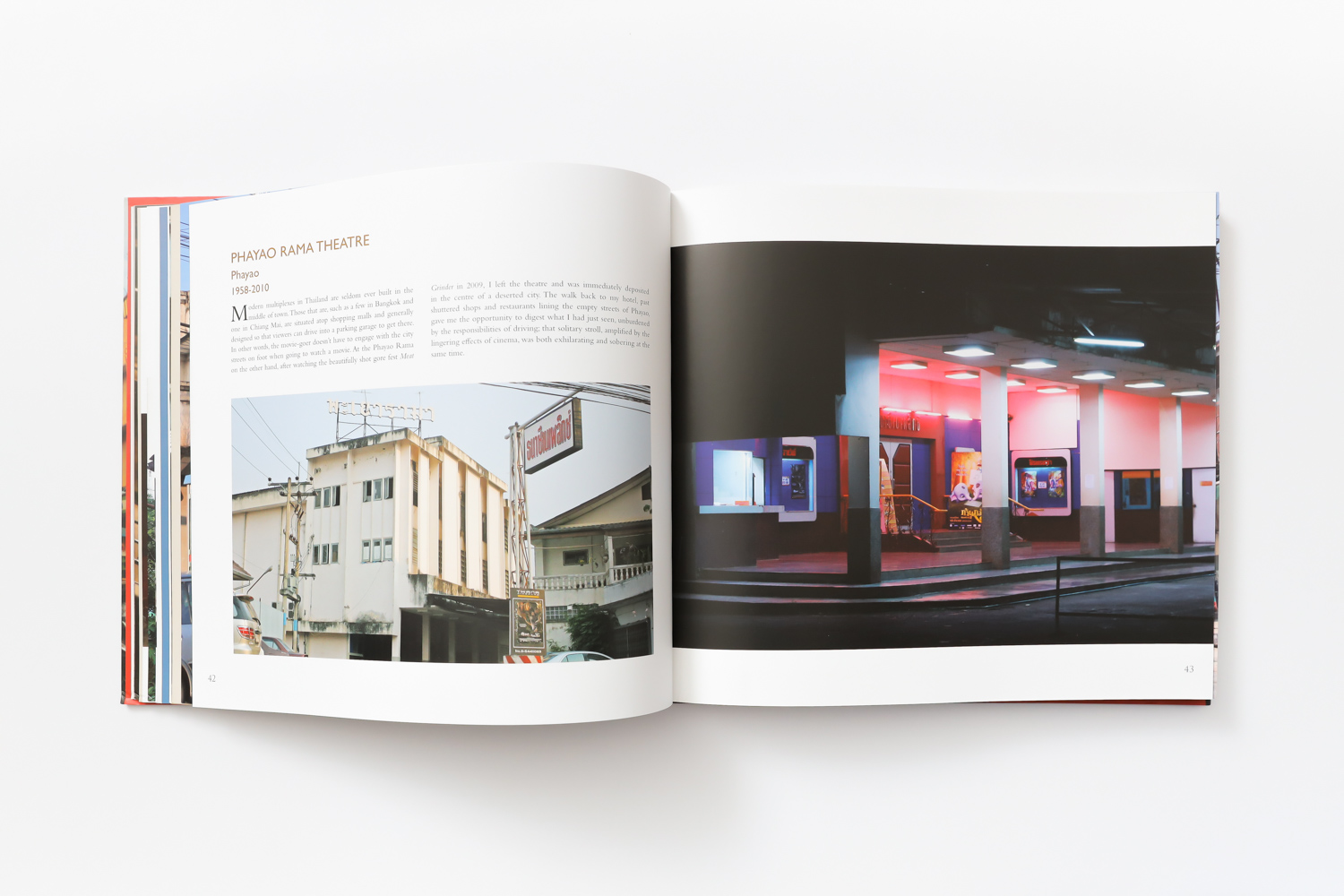

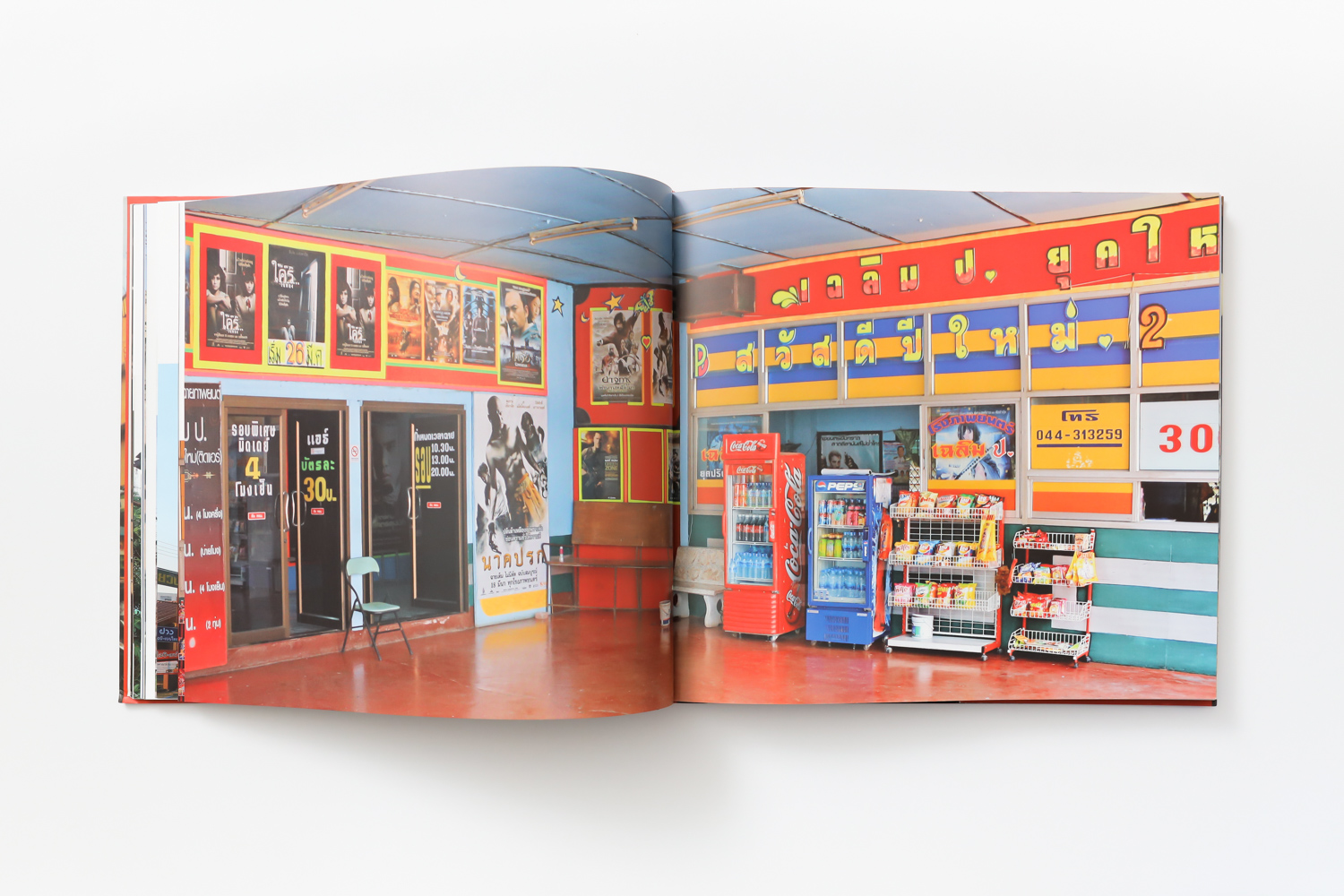

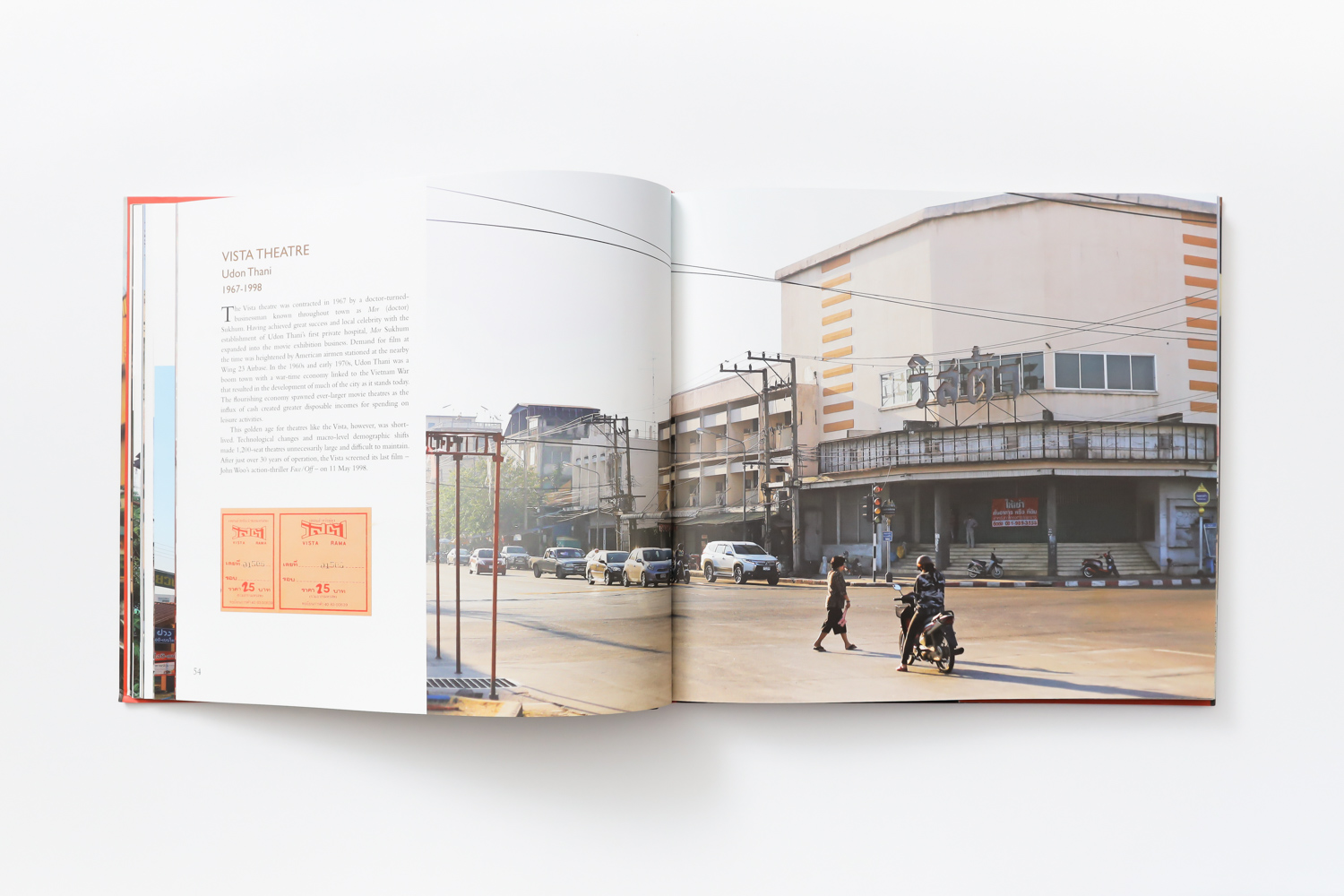

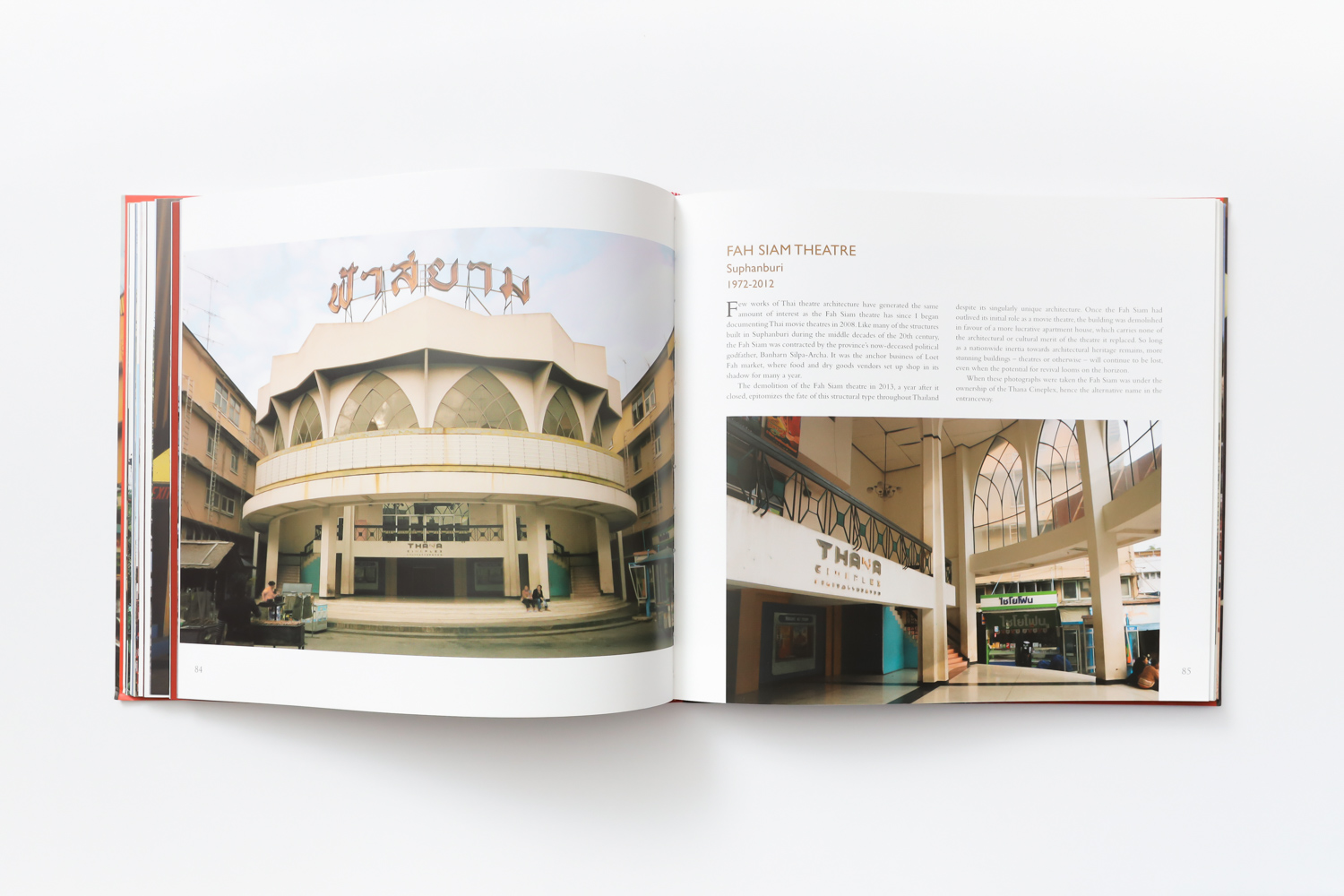

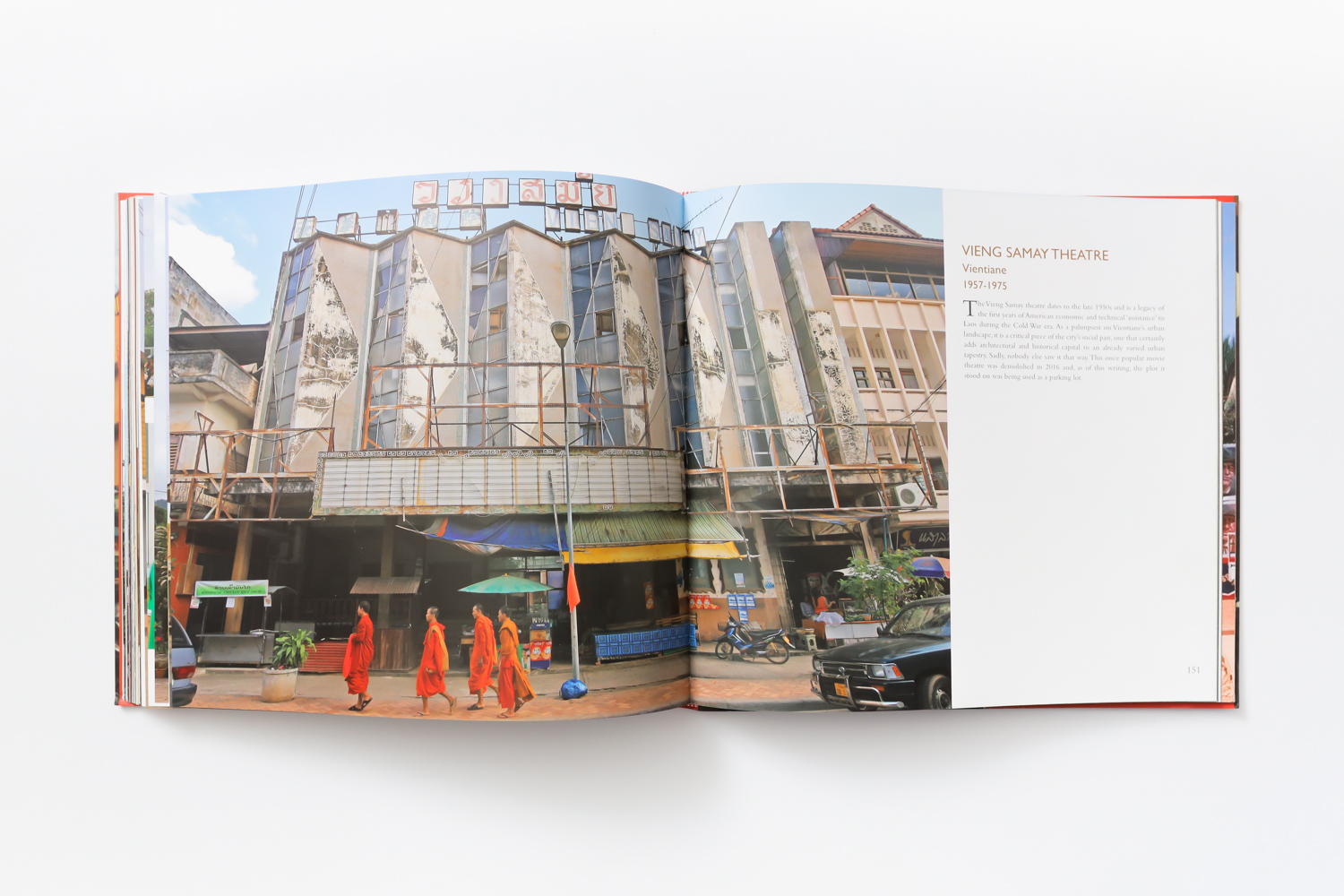

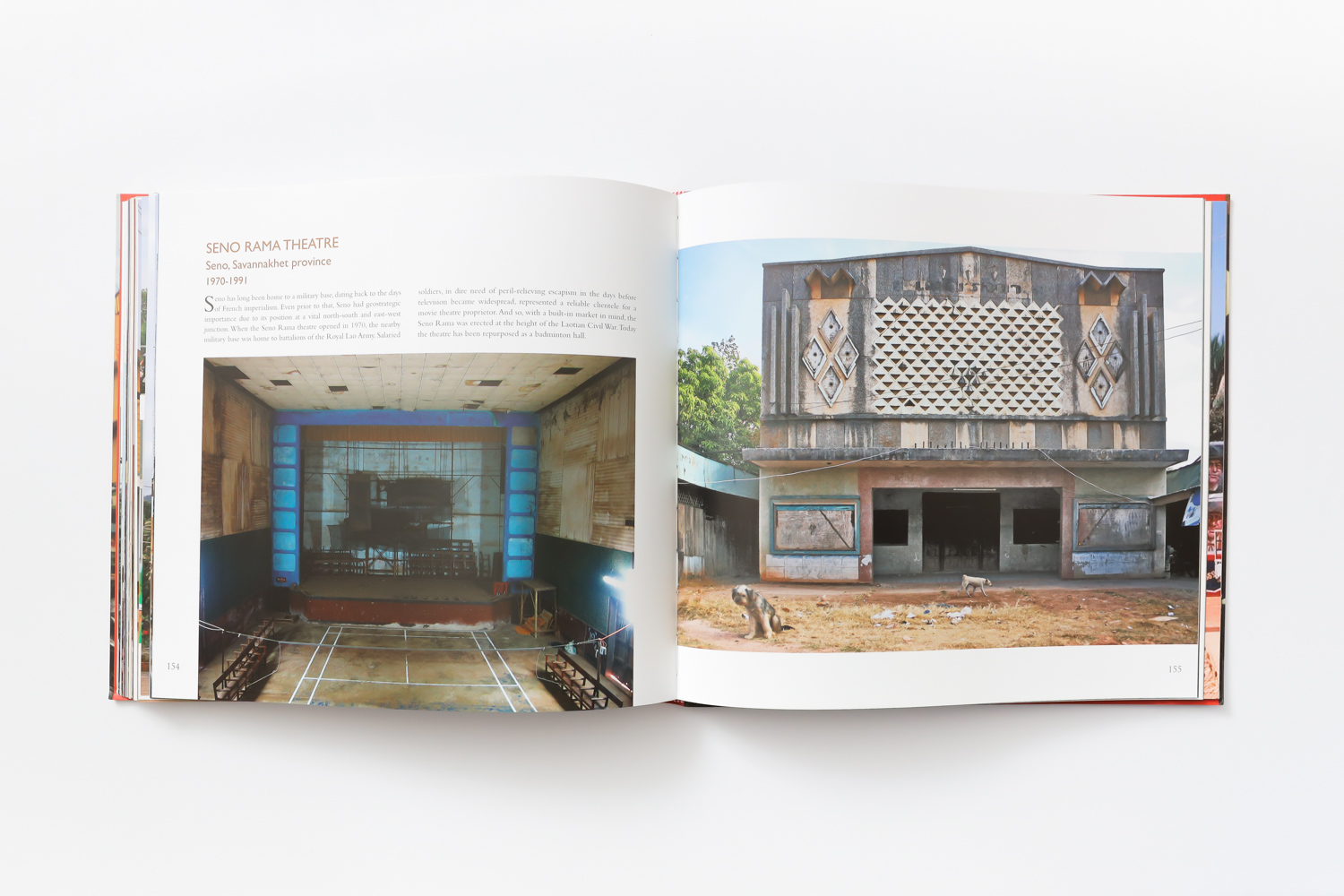

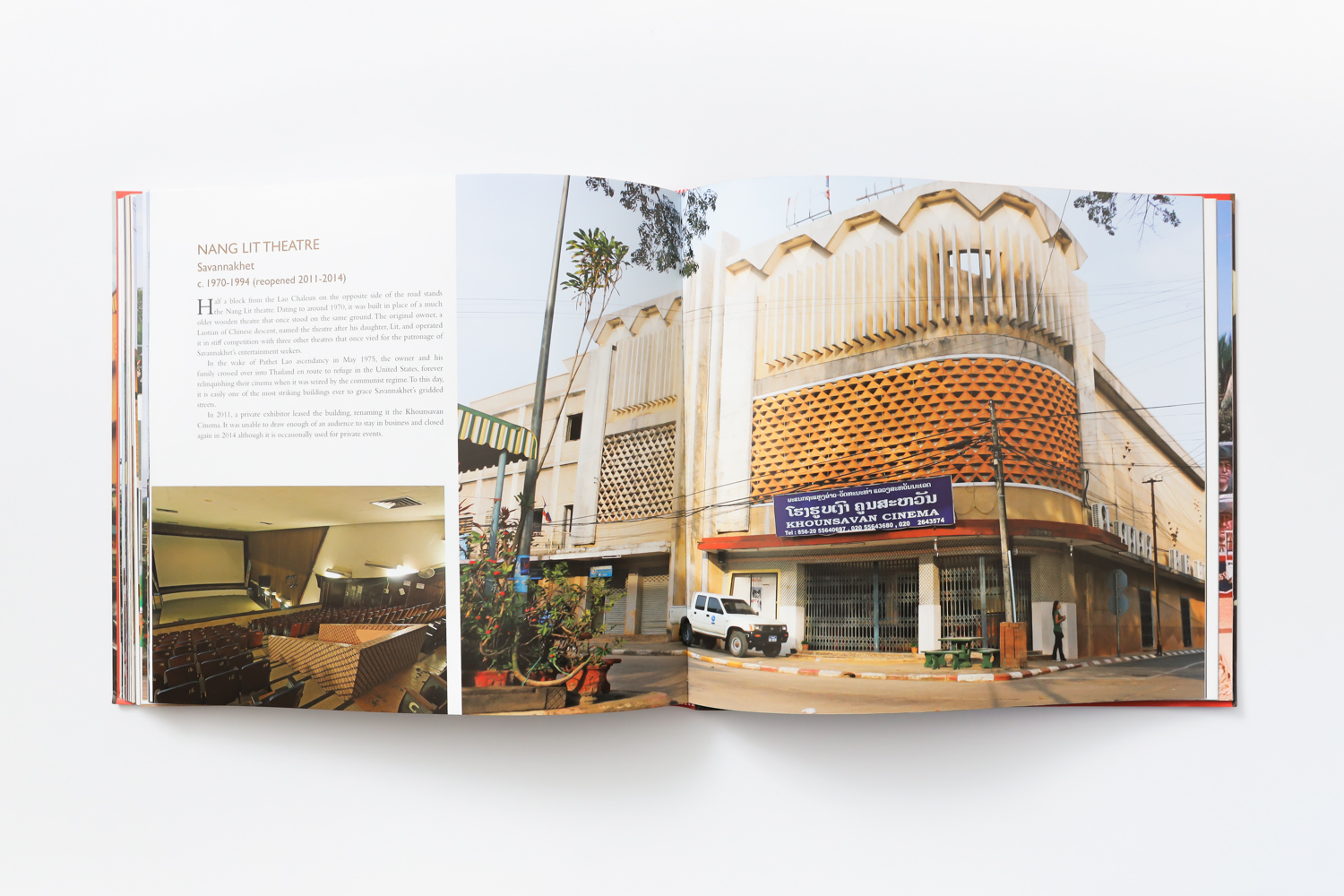

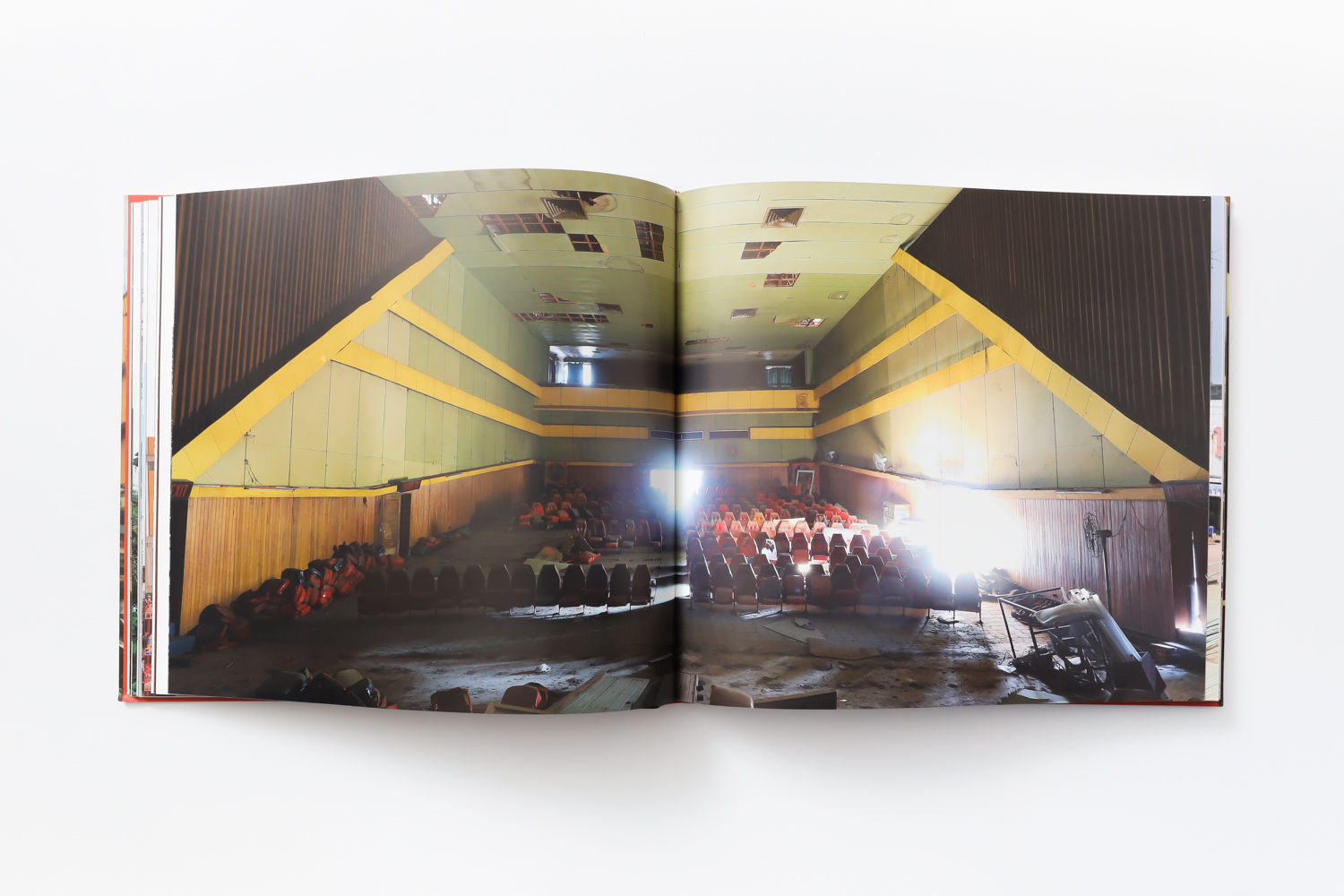

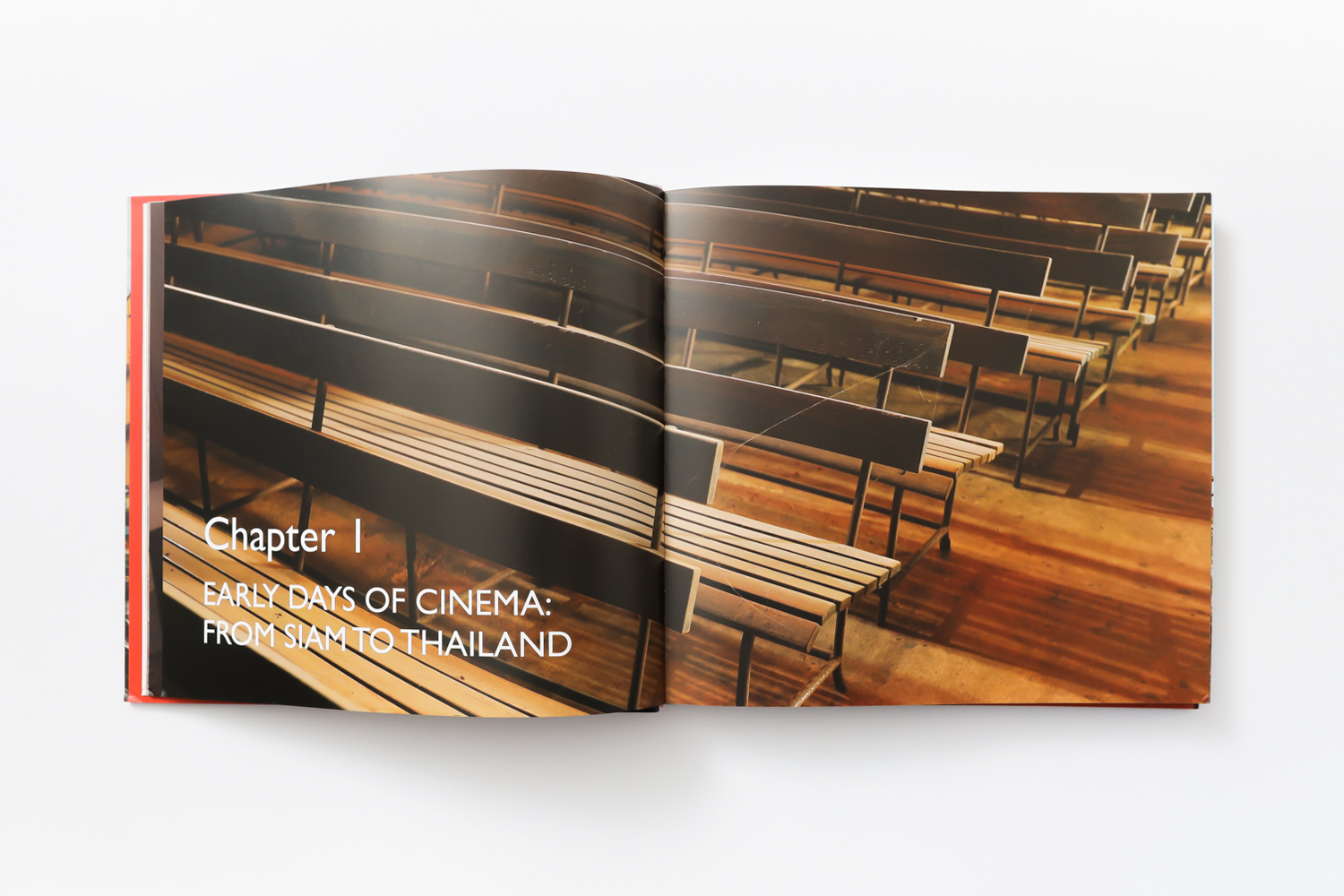

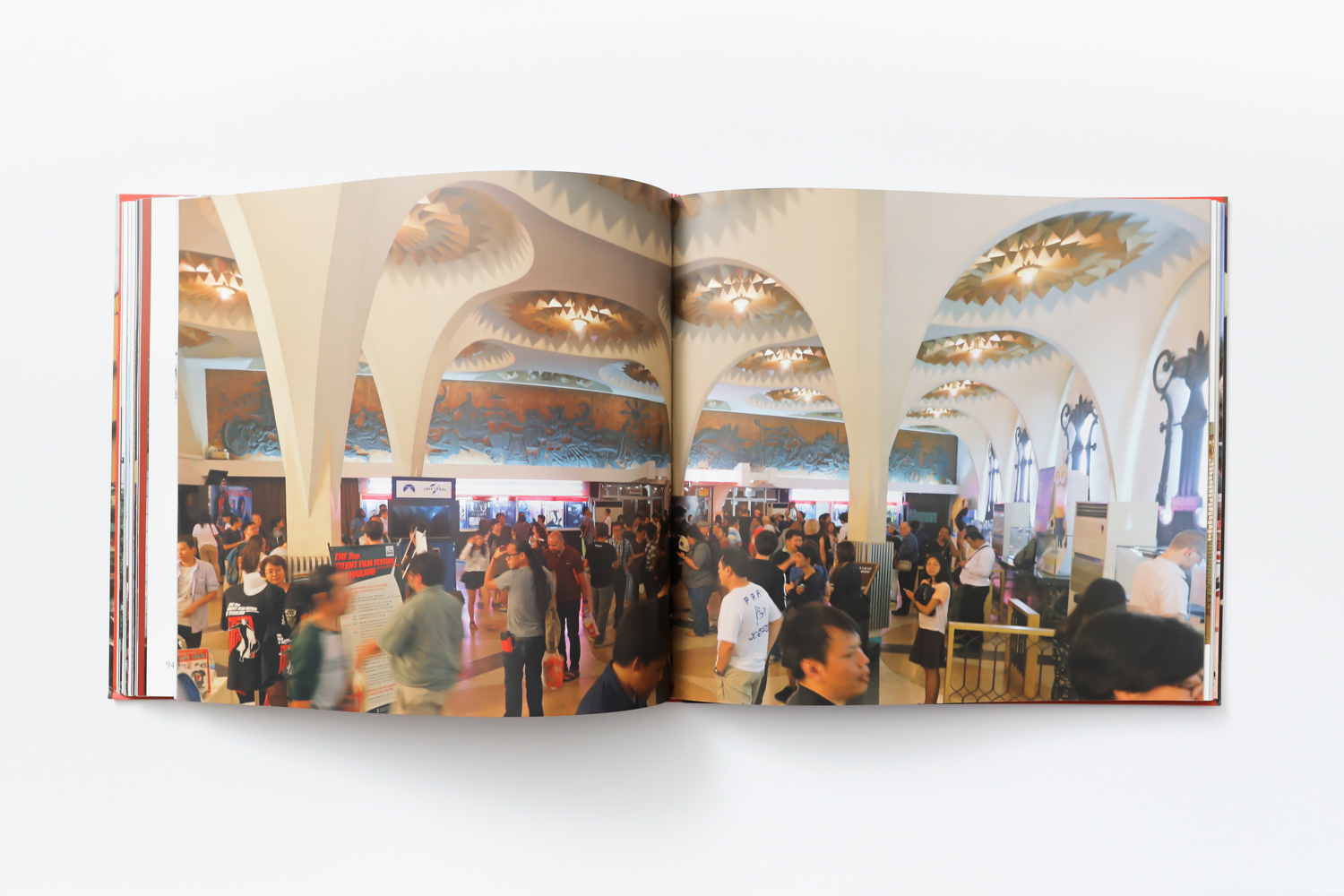

The book, Thailand’s Movie Theaters: Relics, Ruins and The Romance of Escape by Philip Jablon gives off a similar feeling with photographs of stand-alone cinemas built during the 1950s and 1960s across the country and some sited Lao PDR.

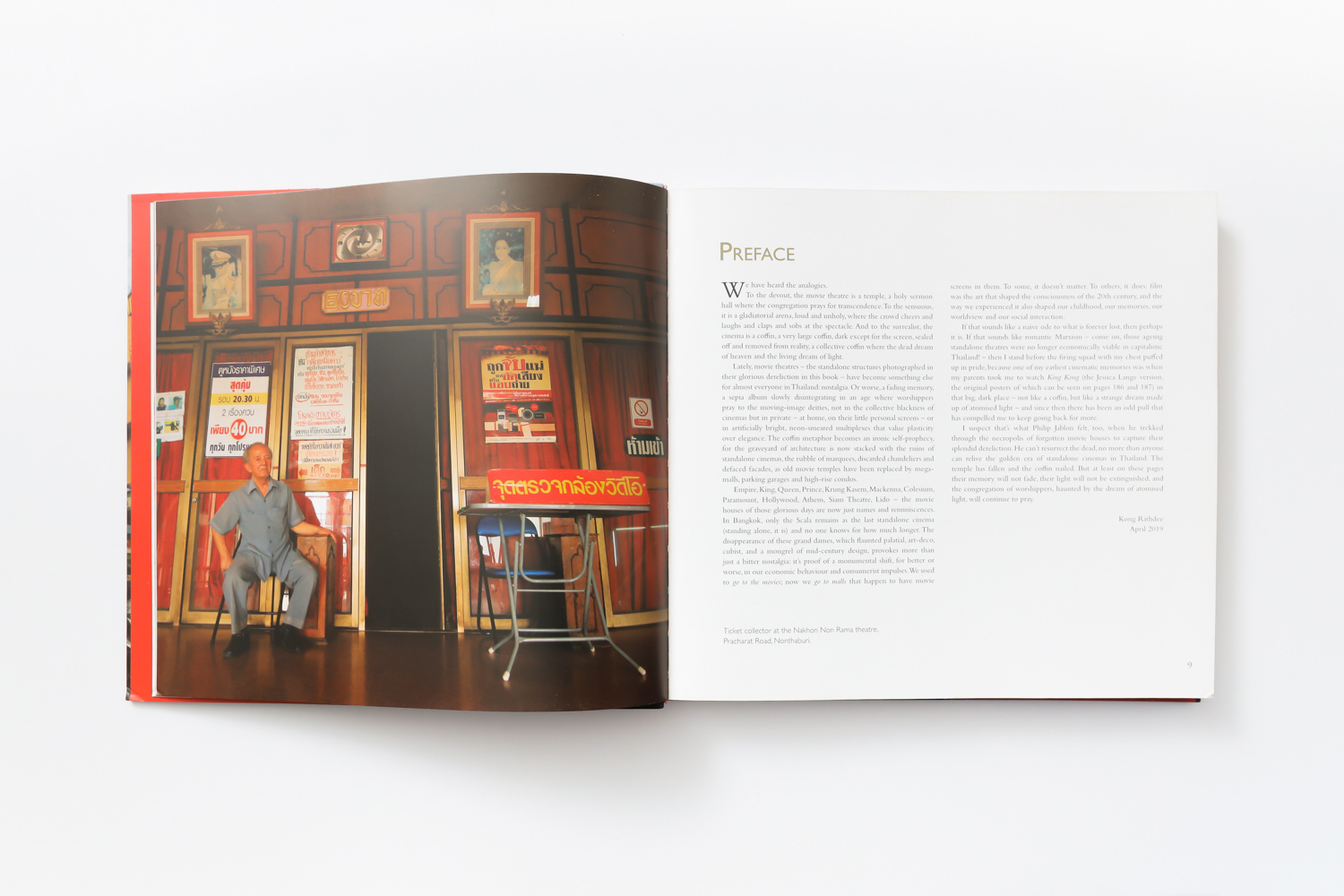

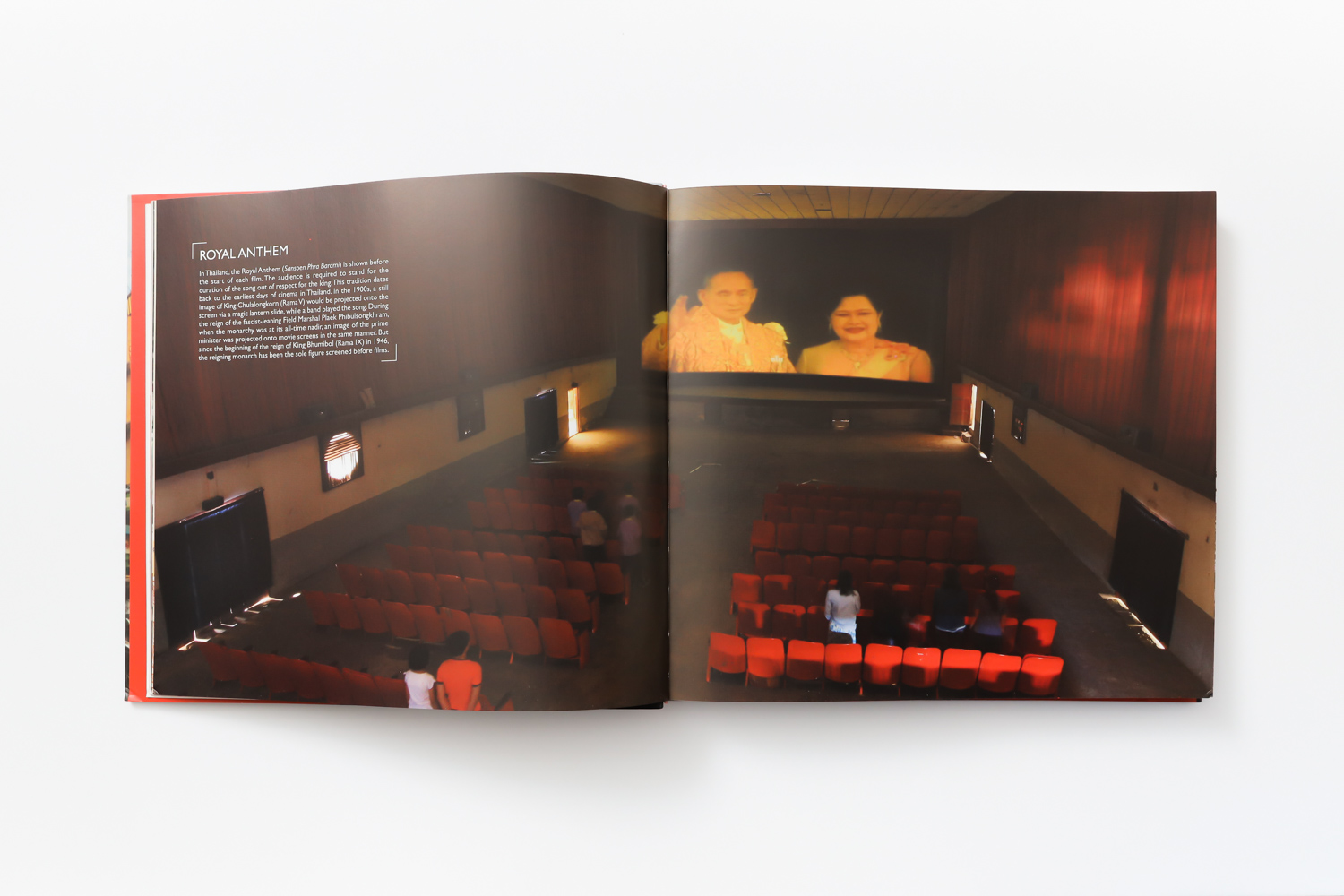

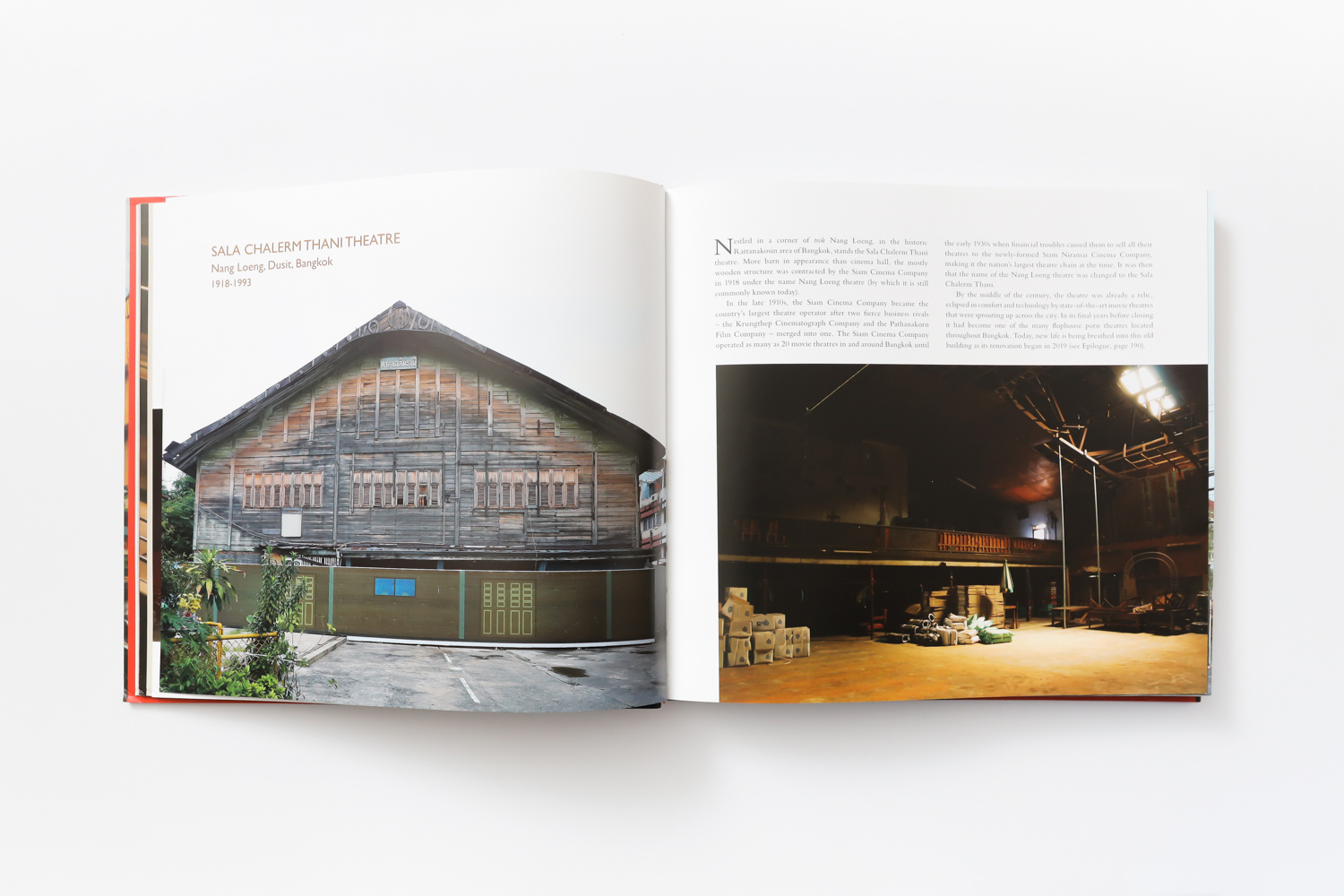

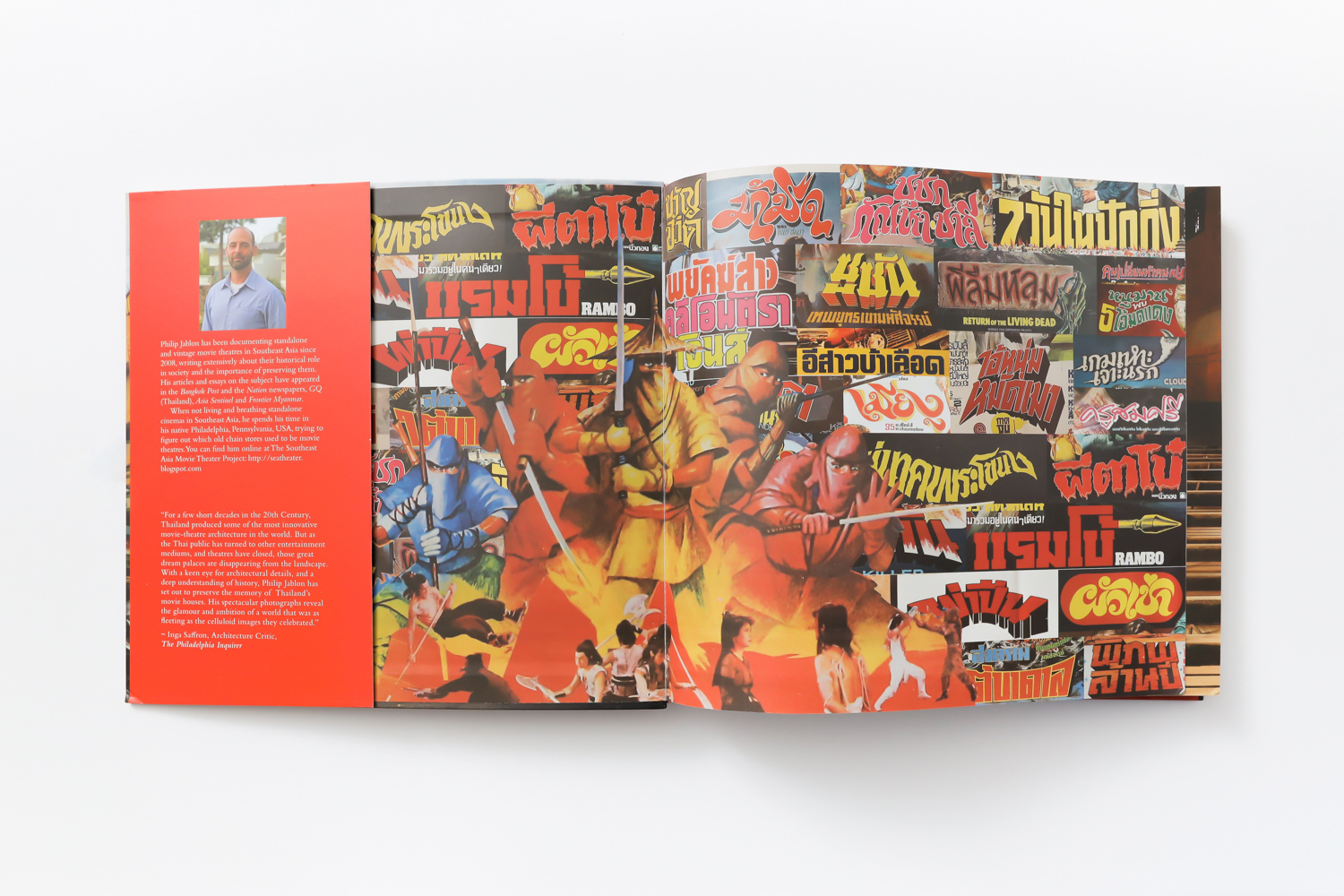

Sala Chalerm Thani, Vista, Somdet, Fah Siam are among many stand-alone cinemas that went out of business and were photographed in the book. The American photographer spent over a decade traveling across the country, taking pictures of these architectural structures. The book is a remembrance of the time when these establishments brought people of all ages, genders and statuses to share a collective experience that films would offer. For a moment in time, they were all within the same dark space with controlled lighting and a big screen. From a historical perspective, movie theaters also have their own place in Thailand’s social evolution as a memorable part of the country’s modernization.

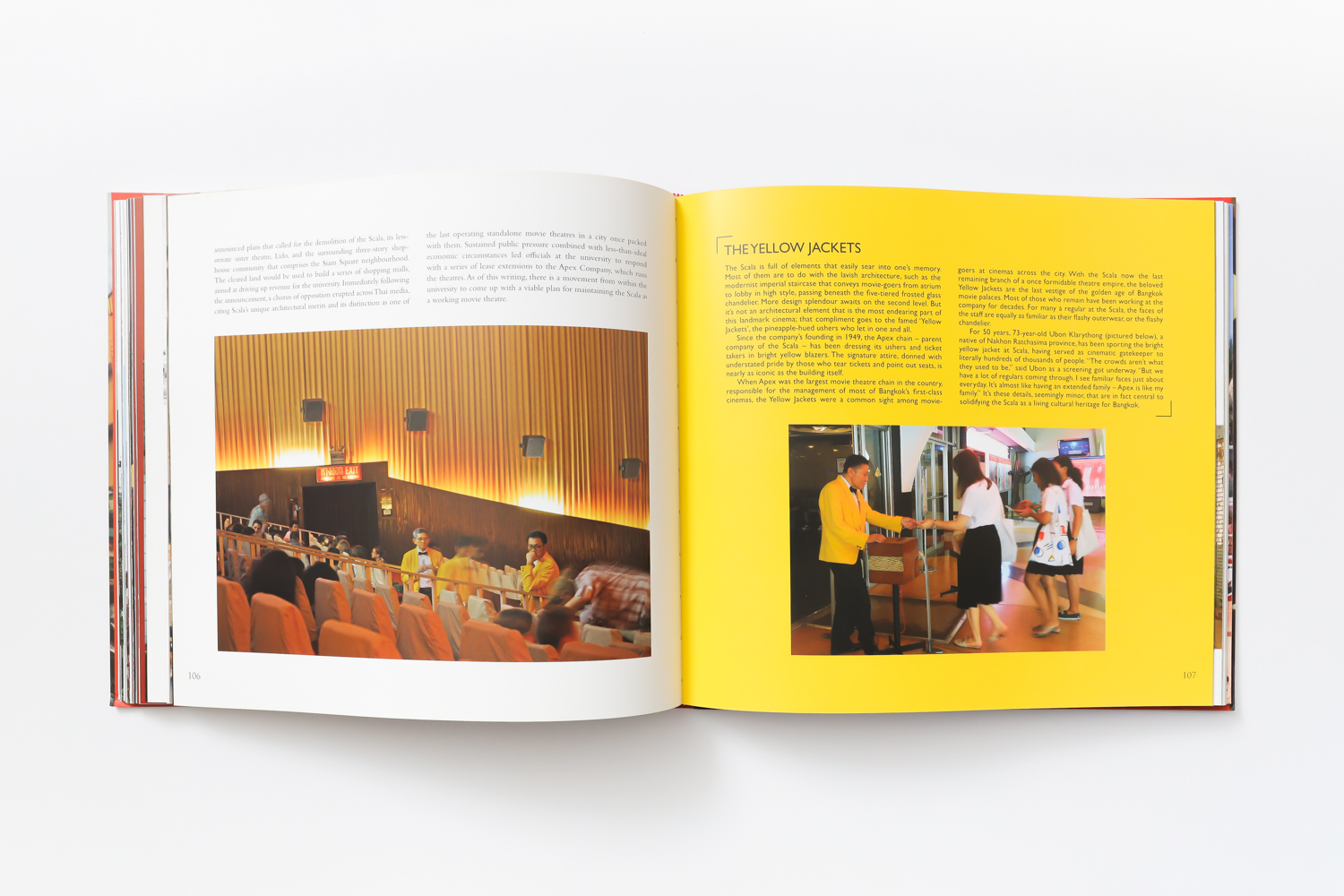

We are seeing multiplexes completely replacing standalone cinemas, despite the images of the last screening of SCALA theater still fresh in our memory, just like the lingering rumbling and feelings of dismay from cinema lovers across the country mourning the end of the iconic movie theater. Who would have thought that the movie theater business would see the day when most spots have been forced to shut down due to the pandemic. Nobody really knows what will happen with this type of entertainment establishment when the day comes where COVID-19 is finally conquered. Will we get to see the livelihood and spirit of movie theaters again in the post-pandemic world, especially with new entertainment platforms being developed to cater to modern-day consumers’ demands and tastes. The screen may be smaller but the streaming platforms offers a greater convenience to the viewing experience.

Having seen all the beautiful photographs featured in this book somehow makes me understand more about the uncertainties in the world. Deep down, I do hope to see at least some of these establishments come back to life, perhaps as a space where a new form of cultural activity can take place; a remembrance of how close Thai people and these local cinemas used to be.