EVEN THOUGH FOLLY IN THE FOREST BY BANGKOK TOKYO ARCHITECTURE (BTA) SEEMS SIMPLE AND HARMONIOUS WITH LUSCIOUS SURROUNDINGS, THE DESIGN FILLS WITH AMBIGUOUS ARCHITECTURAL LANGUAGE AND FUNCTIONALITIES THAT PROMPT USERS TO INTERPRET ITS USE AND MEANING

TEXT: PRATCHAYAPOL LERTWICHA

PHOTO: RATTHEE PHAISANCHOTSIRI

(For Thai, press here)

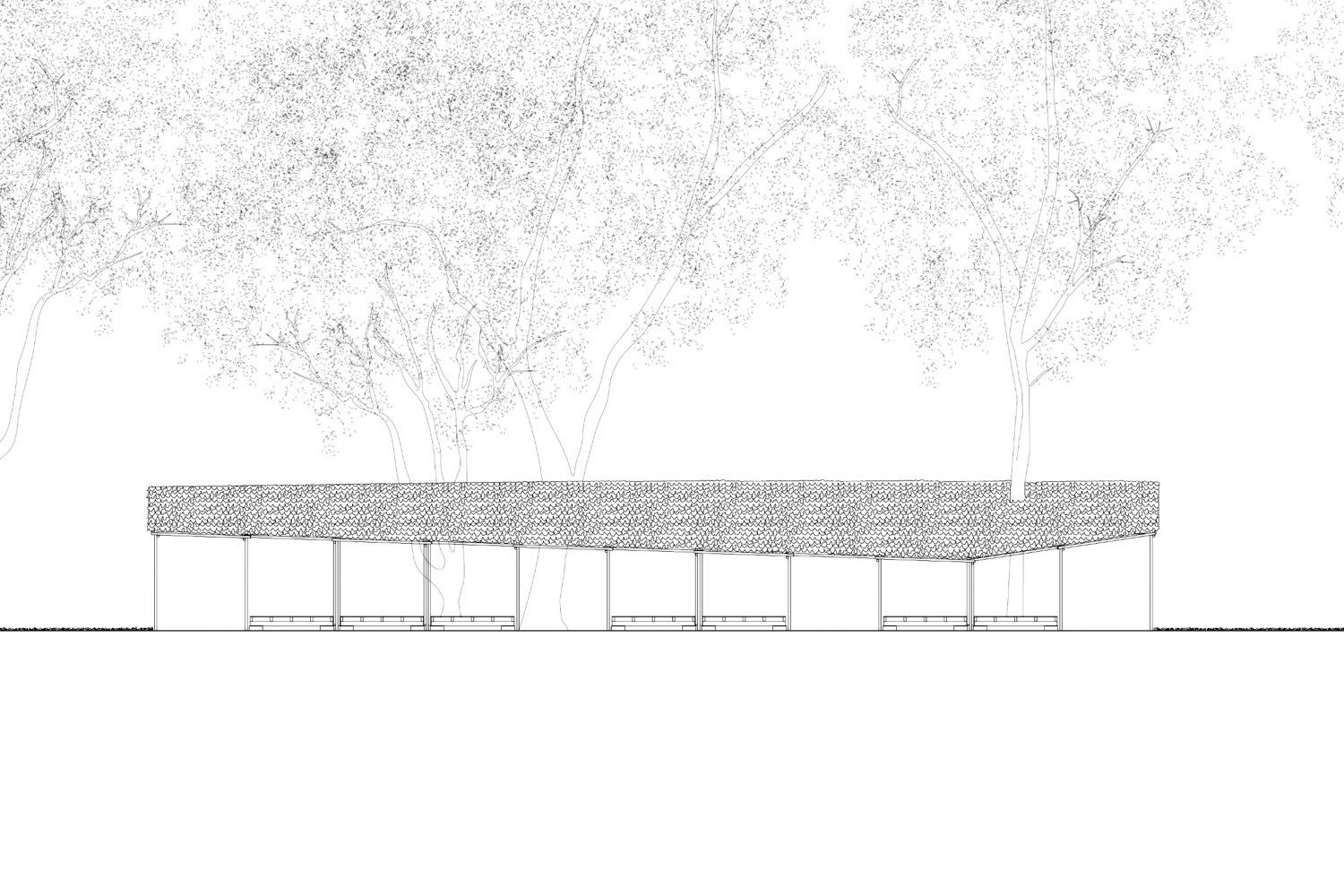

‘Folly’ is the term used to refer to a building with no special functions in a landscape, but is created solely to complete the aesthetic of the green space of which it is a part. ‘Folly in the forest’ by Bangkok Tokyo Architecture (BTA) is realized to bring an interesting addition to the landscape’s aesthetic with its minimalistic presence, which does not only integrate itself as a part of the surrounding forestland, but also brings a lively and upbeat dynamic to the space.

Folly in the forest is a multipurpose building situated in a small plantation forest in Sansai district, a residential neighborhood in Chiang mai, Thailand. The building is born out of an idea the landowner had to create a meeting place for people in the community after the land had been left deserted and unused. BTA is assigned to come up with a building that can accommodate different activities of the potential users, from the area’s residents to passerby and outside visitors.

“The client wants to turn this unused land into a useful area; a communal space with activities that people in the community can participate and enjoy. At the moment, the space is hosting a weekend market while on weekdays, the building serves as a pavilion for everyone to lounge around and relax. But since this project isn’t intended to function as a long-term structure, we have to design a building that is temporary in nature and has the functionalities that can be adapted in case there are changes to me made in the future,’ said Wtanya Chanvitan, an architect of BTA.

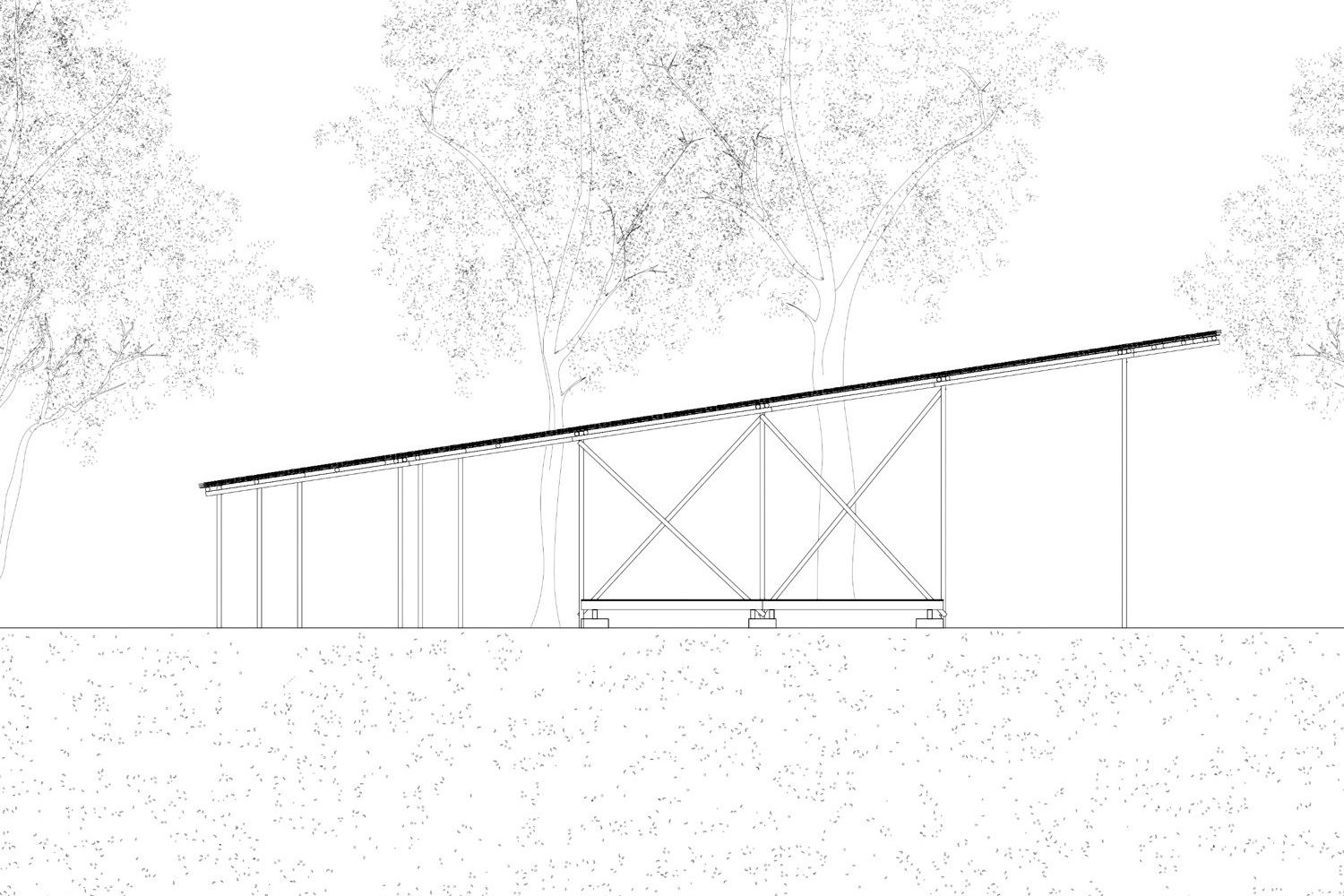

Folly in the forest looks like a moderate-sized shed with a humble appearance. The slant roof inclines from one side at the height of 3 meters to the other side at the height of only 1.7 meters, which automatically makes it necessary for taller people to lower their heads in order to go through. Inside, the building houses a series of round metal columns standing in an organized arrangement, along with metal pipes installed in cross pattern functioning as the partitions. Below, rectangular slabs are slightly elevated in the designed clusters. Wtanya explains the backstory of these components and how they are included to the program to encourage people to interpret and use the space in their own ways, corresponding with the building’s ‘multipurpose’ objective.

“We have installed the interior elements randomly so the building doesn’t have specific entries and egresses, which mean people can enter and exit in any direction. The elevated floor slabs are open to users’ different interpretations. They can be the lots where shops are set up during the weekends when the market is open or a lounging area on other occasions. The slope of the roof creates an interior space with varying heights. Everything is thought of as an attempt to create an environment that is diverse and interpretable through the minimal nature of the design. It’s like when there’s only one tree in a garden, people react to it differently. Some people sit underneath, some bring a chair to sit on, some lay out a mat. We approached the design with this being the main idea.”

The building blends in nicely with the nature with the slender metal poles that disappear into the presence of trees in the surroundings, and a roof that looks like it was completely covered with dried leaves. The roofing material is actually made of dried Tong Tueng leaves fallen from the trees of the same name. This particular species of tree can be found growing in the north and northeastern region of Thailand while its leaves have long been used as a roofing material by people in these parts of the country. BTA employs the local wisdom to the roofing of their ‘folly’ using a construction technique that is similar to a traditional method with the only differences being the use of leakage prevention material and the installation of bamboo stems in calculated ranges to help enhance the roof’s drainage system. BTA adds another detail to the local wisdom by placing stones found in the site on the leaves to seal the edges and prevent water leakage instead of using woven bamboo to cover the top, which is how the roof is traditionally made.

“If we used the bamboo with the roof, the structure would immediately be perceived as a building and we didn’t want that. We want the building to be just this scenery in the landscape,” explained Wtanya about the reason behind the decision to use of stone instead of bamboo.

The traces of the way the structure is simplified and made less noticeable can be found at the joineries of the round metal columns, in which BTA designs to be joined together using screws instead of pipe clamps. Wtanya explains that by using screws, the pipes appear to be separated from each other, consequently accentuating the sentiment that the building is made up of small miscellaneous components, not a large, systematically constructed structure. With these details, the building seems light and delicate, existing as a part of the shades and leaves of the trees.

What BTA creates is a structure with an ambiguous identity and language. Instead of using natural materials with the building’s structure for the entire piece to blend in with the leafy roof and green surroundings, the architect’s use of an industrial material such as galvanized columns end up turning ‘folly’ into a building with a mixture of vernacular and universal accents. The design gets people thinking about whether ‘folly’ is or isn’t a part of its natural surroundings.

From a desert piece of land, the arrival of Folly in the Forest, in Wtanya’s view, has brought new appeals and functionalities to the space. The obscured and unidentified identity of the structure originates dialogues and interpretations about what ‘folly’ really is and how it can be used. What ensue are the livelier spirit and fresher perception of the building and the plantation forest.

“Building a work of architecture inside the space is a better alternative to leaving the landscape deserted and unused because it brings people in to see and use the land,’ Wtanya remarks. “We believe that a good work of architecture should create new possibilities to a space and encourage and inspire people to develop new perceptions toward the space itself.”