INTRODUCING THANAVI CHOTPRADI – A WRITER, AN ART HISTORIAN, A PROFESSOR, AND A CURATOR WHOSE NAME IS CIRCULATING IN THE CONTEMPORARY ART SCENE FOR DECADES, AND TALK ABOUT HER ROLES ON TAKING THE ART VIEWERS TO EXPERIENCE OTHER ASPECTS OF ART, IN ADDITION TO THE INFLUENCE OF THE CREATOR

TEXT: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PHOTO CREDIT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Thanavi Chotpradit is one of names that has been circulating Thailand’s contemporary art scene for the past two decades. We’ve seen it popping up on newsfeeds, in articles published by The 101 World/Same Sky magazine, Arn journal, pamphlets of art exhibitions and talks. The one incident that caused quite a buzz was the open letter Thanavi wrote to the curator of ‘The Truth_ to Turn It Over’ exhibition in South Korea in 2016 regarding the inclusion of the piece ‘Thai Uprising’ by Sutee Kunavichayanont. Thanavi’s many roles include an art historian, writer, professor at the Department of Art History at Silpakorn University’s Faculty of Archaeology, a contributor of academic journal, Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, and her latest responsibility as the curator of Phantasmapolis 2021 Asian Art Biennial held in Taichung, Taiwan.

Thanavi graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the Department of Art History of the Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University. In the early 2000s, her main interest was geared towards Contemporary art, which compared to now, was a less accommodating time for one to learn about this particular genre of art. “I knew since I was a student that I liked Contemporary art, so I was trying really hard to write and get my works published.” The first pieces of writing she did were published in Art Record magazine. Thanavi told art4d that she started the job at the publication as a volunteer staff, doing proofreading before finally getting to write small news articles and interviews.

“I was very driven and determined to write. So at the time, I was submitting my articles to newspapers as well. I remember participating in a research project called ‘criticism as an intellectual force of a contemporary society.’ The workshop was facilitated by Dr. Chetana Nagavajara and the participants were students who wanted to write critical think pieces on art. It was 2003, Bangkok University was hosting the first Brand New exhibition so I wrote about two works, one was by Yuree Kensaku and the other was by Arin Rungjang and the pieces were published in Kwan Ruen magazine and in the ‘Jood Pra Kai’ (Inspire) column in Bangkok Biz newspaper. I was in my senior year at the time.”

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

After graduation, Thanavi spent almost five years searching for what she wanted to do. “The problem was I knew that I liked Contemporary art but I wasn’t sure what I would do with it.” Apart from writing articles, she worked with Klaomas Yipintsoi at a non-profit art organization, About Art Related Activities (AARA), which operated an art space called About Studio / About Café, as a part of the curatorial team. “My job was to write articles for the exhibitions that were featured at the space but I wasn’t the one choosing the artists or the works.”

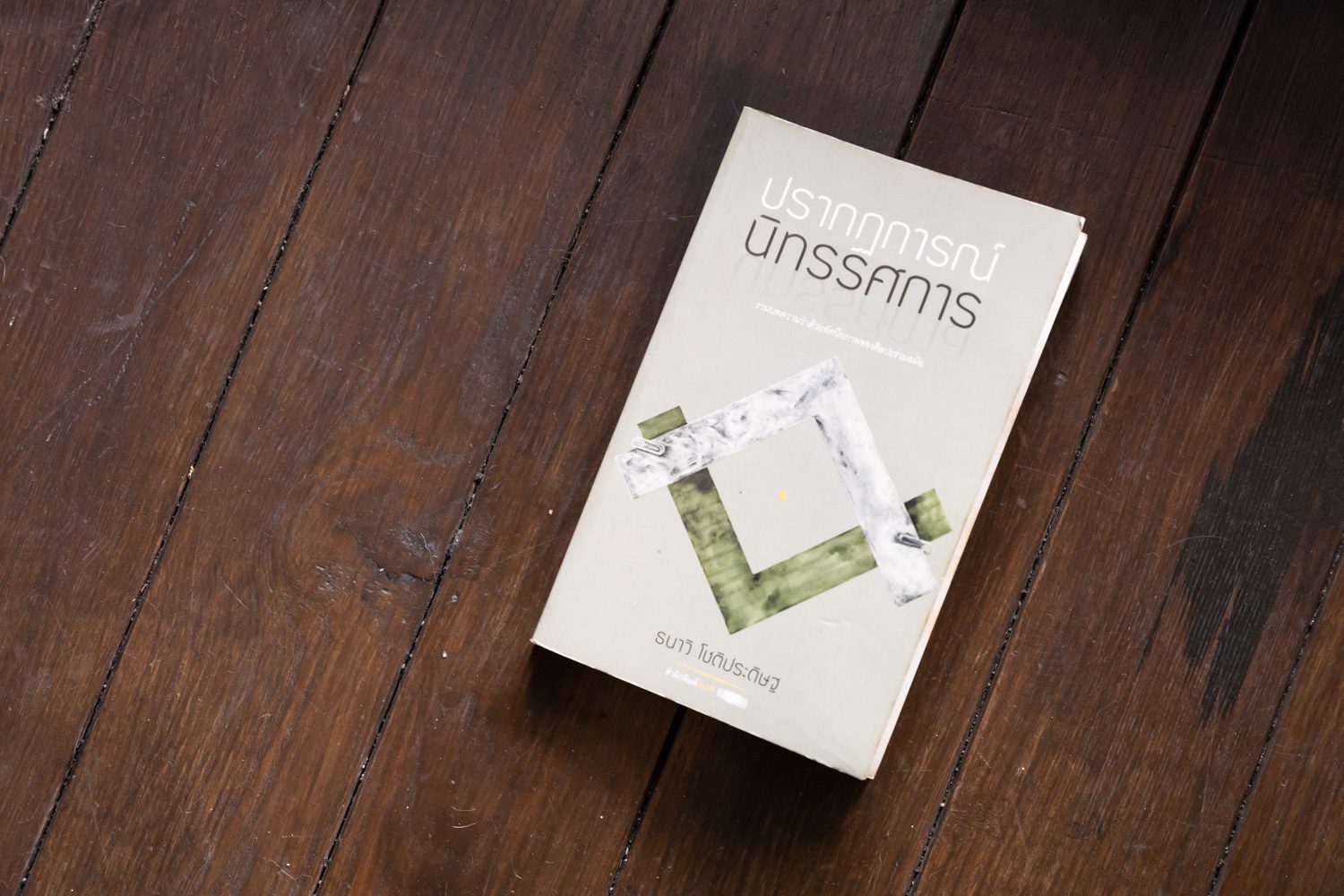

Ultimately, art management or curatorial practice were crossed off the list of her career choices (even though she has been given the role of a curator later in her career), Thanavi chose the academic path and pursued her master’s degree in art history at Leiden University, the Netherlands, and a PhD in the same field at Birkbeck, University of London. She graduated with the thesis titled ‘Revolution versus Counter-Revolution: The People’s Party and the Royalist(s) in Visual Dialogue,’ which involves the political power of art created during the rise of The People’s Party. After graduating, she came back home and took the position as a art history professor at the Department of Art History, Faculty of Archeology, Silpakorn University, the position that has now become her full time job until today.

Pratchaya Phinthong, Broken Hill, 2013. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery I Photo: Mark Blower

Pratchaya Phinthong, Broken Hill, 2013. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery I Photo: Mark Blower

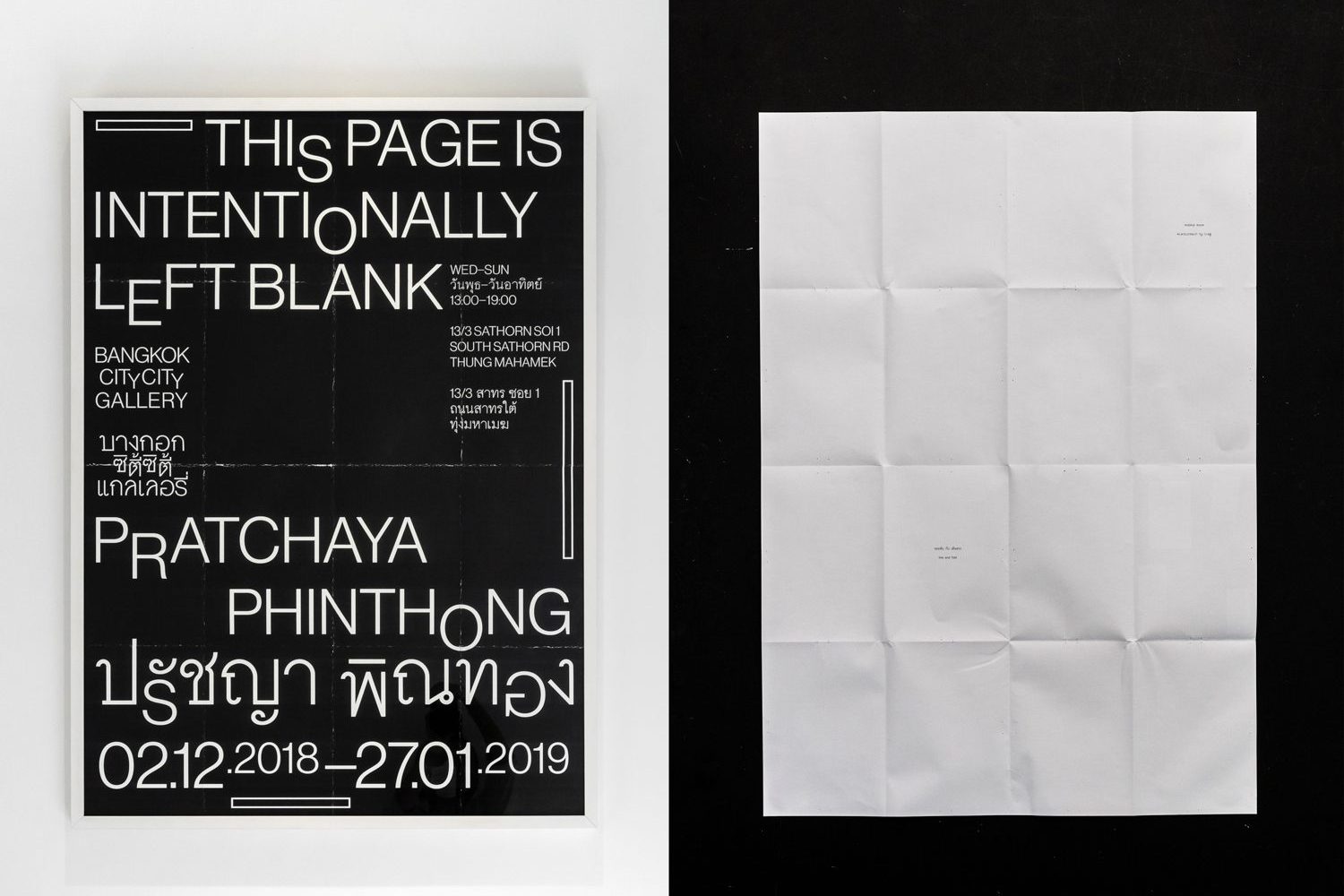

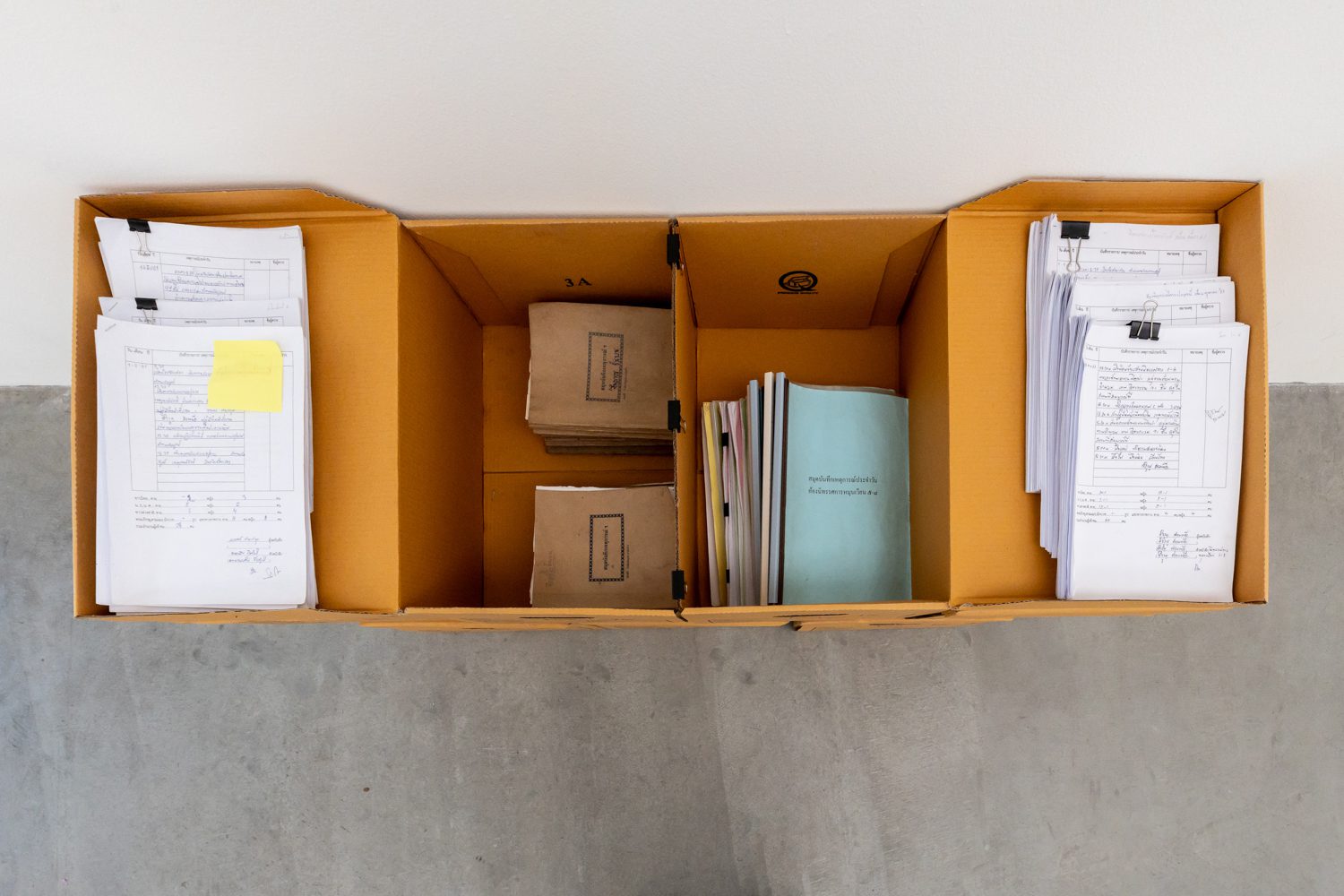

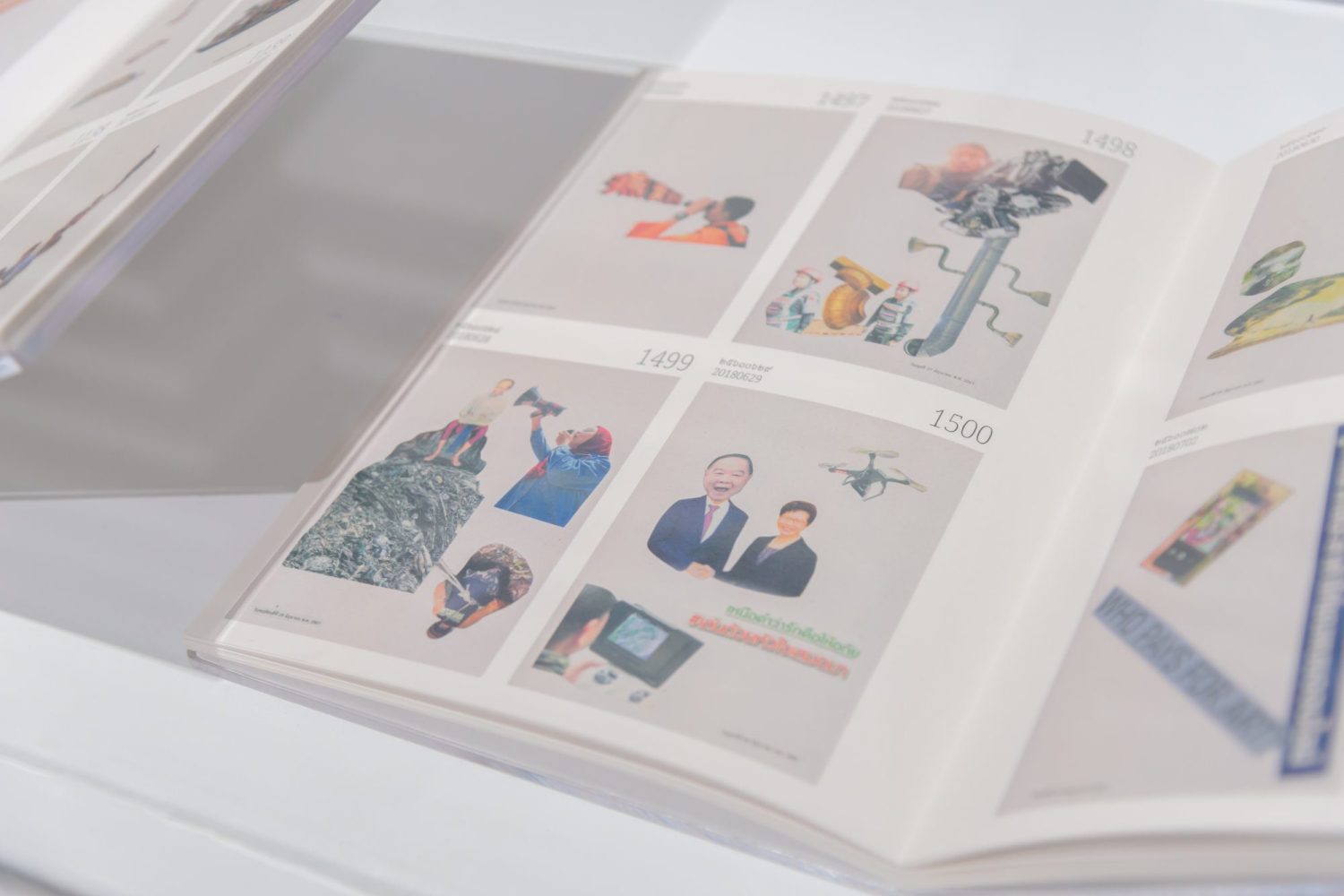

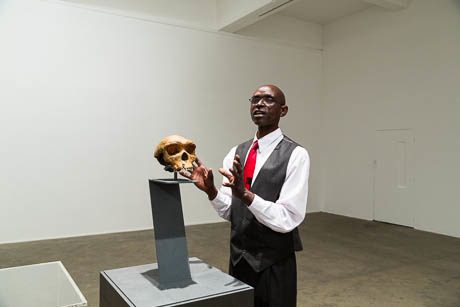

“It just so happened that Pratchaya Phinthong’s ‘Broken Hill’ exhibition (2013) at Chisenhale Gallery was taking place while I was doing my PhD in London. I had been following his work and had this urge to write a long article about it.” (‘Broken Hill: A Calling from Africa’ was published in Damrong Academic Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2014). Thanavi recalls that one of the subject matters she always notices in Pratchaya’s work is Institutional Critique. Regardless of medium and space, this trace is something that can be found in his work. The observation caused her to discuss the subject matter in ‘This page is intentionally left blank,’ the exhibition at BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY she curated in 2019. The curatorial program was materialized as a recreation of parts of National Museum and National Gallery’s exhibition spaces inside a commercial gallery with an additional role of an alternative art space.

This page is intentionally left blank I Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

With Phantasmapolis 2021 Asian Art Biennial, Thanavi brought ‘Gives Us A Little More Time’ (2020) by Chulayarnnon Siriphol to the Taiwanese audience for the idiosyncratic sci-fi flair the work possesses. “Chulayarnnon has this ability to make dark subjects like the vile and unforeseeable situations in Thai politics comedic without sugarcoating the violence of the reality that is happening.” Thanavi was also the curator of the non-exhibition portion of event, which comprises the curators’ forum ‘Songs from the Moon Rabbit – Forum of 2021 Asian Art Biennial and the book of essays, ‘Midnight Sun and the Owl,’ which is set to publish in 2022, around the time in between the previous and next biennial. “The way I think when I work, whether it be organizing a forum, writing or selecting artists for Phantasmapolis, is the same. I engage with the works and the artists and I use them as the foundation, which later leads me to build all these connections with the theme and keywords. I try to create this ‘balance’ in the relationships that will happen between everyone involved, from the artists, the curatorial team and the organizer, which is the museum’s team, all the way to lecturers who will be speaking at the forum and the writers I invite to write something.” The objective is for the dialogue to ramify beyond the exhibition and allow everyone to participate, one way or the other.

For Thanavi, being a critic, an academic and a curator are similar for the way all these roles center around researching. The difference, however, lies in the final result, which is rendered in various forms and formats. The most difficult aspect is finding the right balance. “With Pratchaya’s works, I may think Institutional Critique is one of the most distinctive characteristics of his body of work but perhaps that’s something the artist has never thought about.”

Phantasmapolis I Photo: Napat Charitbutra

Phantasmapolis I Photo: Napat Charitbutra

“I don’t need to know what an artist was thinking, at least not 100%, but I don’t neglect the fact that the person is the creator of this particular work so I must not destroy the work for the sake of my own creation. So, it’s important to find that balance, but the difficult thing is I can’t really pinpoint where that balance really stands.” Thanavi gives a simple example of the balance she’s talking about, which is basically the point where everyone involved reaches a mutual understanding and satisfaction. Nevertheless, what’s even harder than being a critic or a curator is having to deal with artists, viewers and society’s expectations, especially in Thailand, the country that is hyper sensitive when it comes to criticism. Writers (and at times, curators) are perceived as merely a messenger who reports on artists’ ideas and sentiments. “When I was a student, I used to ask this artist what curators do and his reply was they’re like our hands and feet. The answer kind of stunned me.”

Thanavi thinks that one of the major problems is the mainstream public opinion in Thai society, which has a mindset that those who critique need to know how to do the thing they are critiquing. It’s something along the line of ‘if you can criticize how this country is run, then why don’t you try running the country yourself.” This similar set of attitudes can be found in the way art is critiqued, causing the right to give criticism to fall only in the hands of the creators or the people who have the ability to create (such as artists who are also writers). art4d asked her, what if the ability to create serves as a ground that gives artists’ justification to criticize, then what ground do writers/art critics stand on when they write or express their opinions about art? Thanavi simply replies, ‘it’s the freedom to voice your criticism.”

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

The ground that art historians stand on is their thoughts and views on art, which can be expressed verbally or through a piece of writing. In this world, there are other aspects (history, social science, technology, etc.) in addition to brush strokes and visual elements that can be utilized to form and deliver critical and constructive criticism. “Even art history as a discipline has gone through its own changes and it picks up things that are outside of its realm to apply and accompany one’s thoughts and points of view.” Art historians do not have to try to search for the ‘truth’ in a work of art (which in reality is closely associated with the artist who creates the said work). We add more explanations to the work using other viewpoints, because otherwise, art will die, is what Thanavi said.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Similar to her role as a curator, Thanavi recalls the time when she was working as a museum guide for the Beyond Paradise: Nordic Artists Travel East exhibition at the National Gallery back in 2000. “It was the moment of enlightenment for me where I finally understood what a curator’s role really is. There was this work called Excerpt from Already Elsewhere, 2001 by Swedish artist, Maria Friberg, installed near a door of the exhibition room and the cold air from the air conditioning system was blowing right at the spot. When Dr. Apinan Poshyanada, who was the curator of the exhibition, walked in and the tour was about to start, he was hugging his chest and said, “I want the viewers to feel cold.” It shows how a curator is someone who works with art pieces and thinks about how a certain work should be perceived or experienced, how this particular work should be placed at this specific spot. It isn’t about waiting on someone’s hand or foot.”

Maria Friberg . Excerpt from Already Elsewhere, 2001 I Photo courtesy of the artist

Thanavi ended our conversation with her view on how curators or critics should stand their ground by saying to the society and the public that the space between artists and viewers is big enough for writers, critics or curators to exercise their ideas. This ‘space’ (which most people fail to see) is vital to the way viewers can be taken to experience other aspects that also have a great deal of impact on a work of art, in addition to the influence of the creator or artist who is behind the creation of the work. And most importantly, there’s plenty of room in that space for viewers as well.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan