IT SEEMS LIKE HUMANS ARE COVERTLY PROPELLED BY STORIES WE HAVE BEEN MADE UP OF: GOD, DEMOCRACY, OR CAPITALISM. ARIN RUNGJANG REVISITS FICTION AND POWERS THAT SHAPE HUMAN SOCIETY INTO WHAT IT IS WITH HIS ARTWORKS

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Scents and sounds were the first two things that all of your physical senses would experience as soon as the entrance to Gallery VER opened.

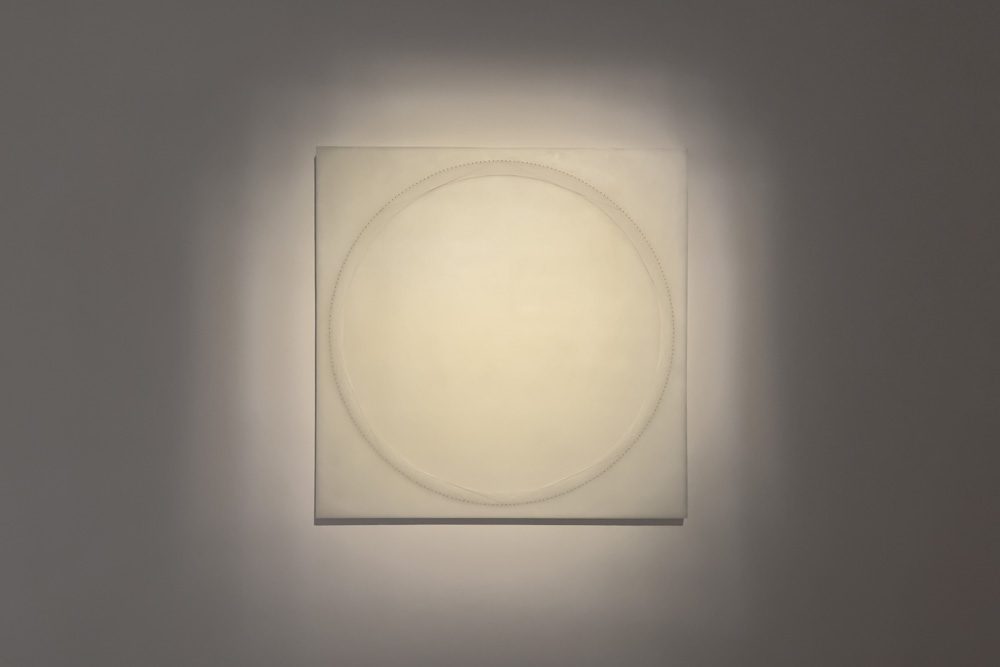

The lingering aroma in the air is reminiscent of the incense used in the worship of gods or Buddhist religious activities in a temple’s main hall or sacred chambers. The sound of a woman reciting lines in a monotonous and chilling tone was also heard. When you removed your shoes at the doorway (as directed by the sign) and entered the exhibition room, each of your steps would make contact with the soft carpet that covered the entire floor. Your feet would feel as if they had entered another realm, utterly detached from the roughness of the floor you had just walked on. Perhaps this was an entirely different world. The fluffiness and cream hue of the carpet would also entice you to take a seat and spend some time contemplating each work of art. The sound of the women from the recording could still be audible, with repeated words whose meanings were impossible to grasp or decipher…if there was any meaning at all. I sat and stared at the sculpture, which was made up of multiple rows of strips dangling from the ceiling. There was also a pure white abstract wax painting that appeared to be a circle from a distance. Details of Sai Sin (the white sacred thread used in religious rites) were revealed up close, with strings tied to the tiny brass pins into an octagonal configuration within the circle. At some point, a video of distorted moving images in a nearby darkroom would draw your attention. After a few moments of seeing those images move, you’d realize they were of the lotus mural painting by Khrua In Khong, the masterful and avant-garde painter prominent during King Rama 4’s reign.

Before delving further into “We will leave and never return,” let me take you back to Arin Rungjang’s previous solo exhibition, “Oblivion,” which took place at Nova Contemporary last year. In that exhibition, the artist incorporated objects containing remnants of the memories of kings, miners, and even the artist himself. Also included were recollections of his own sister, whom he saw as oppressed by society as a woman with a failing marriage, which led to her fight with stress and depression and eventually her death.

“We spend our lives without knowing what sorts of fictions are controlling us, and we leave traces of those memories in various objects,” Arin eloquently and beautifully summarized his thoughts with the latter statement that sounds particularly poetic. According to Arin, the ‘fictions’ that dictate our lives are all made up. In his view, everything is fiction.

“This entire world has been shaped to be propelled by the potential of all these different things.” Humans drive a society in which humans are the primary members. And one of the potentials that humans have is the ability to calculate and speculate on the possibilities of events based on the way we think about a certain story. Stories that have been made up, whether about angels, God, democracy, capitalism, or digital culture, are fiction that humans construct based on their capacity to predict what will happen next.”

Fictions based on human thoughts and feelings have been around since the time of animism. Humans venerated myths and spirits, using their imagination to relieve their fear and lack of knowledge, glorifying nature as representative images of gods. They worshipped stones, trees, weather conditions, and so on. Humans turn gods into natural forms and then into something more substantial as their knowledge began to grow. Complex figures such as gods, angels, and prophets from various religions were then created.

“It’s a shift in our spiritual collective consciousness,” Arin explained. “When we denied nature, we began to look to God; when we refused God, we developed a new consciousness. This time, we put ourselves in the center. These functions can be seen in paintings, writings, and so forth. One example is how mural paintings created before the 15th century do not contain anything relating to humanity. These paintings depict the might of these beings, such as the enormous, imposing-looking Godly figure. Less powerful characters are physically smaller. But it wasn’t until the 15th century, when mankind began to reject God and place greater value on themselves, that artists began to regard humans as individuals.”

In Thai history, Khrua In Khong was the first artist to use the linear perspective technique to produce mural paintings with three dimensions, equivalent to what human eyes could see. Aside from the techniques, Arin is interested in the stories included inside Khrua In Khong’s paintings and how they evolved from stories of the Buddha’s life or literature, such as Ramakien, whose storyline was based on India’s Ramayana epic. King Rama 1 commissioned painters to produce a mural painting from his literary rendition of Ramakien on the walls of the serpentine terrace around the Temple of the Emerald Buddha’s ordination hall, a tradition that King Rama 2 continued. Nevertheless, King Rama IV ordered Khrua In Khong to create pictures in which dharma teachings were disguised in symbolic puzzles, signifying a shift in emphasis from a person to the teachings. The paintings presented Buddha as a common man with exceptional intelligence, rather than the god-like character often depicted in artworks based on ancient tales about the Buddha’s life. Not only that, all of the characters and settings in Khrua In Khong’s paintings were western.

“We took the Ramayana epic from the Khmer and rewrote it during King Rama 1’s reign. Ramakien was thought to be the very cornerstone of the theorem that would later impact Thai society’s governing structure.” Arin’s viewpoint is similar to what Indian author Arundhati Roy suggests in one of her books, which discusses how the Ramayana is the justification for the Aryans’ invasion of the native Dravidians as well as the Indian class structure. “But King Rama 4 asked for Khrua In Khong to remove all pre-existing texts. His paintings did not depict the king or any individuals who would fight the Orcs. They were very scientific, with stories about the solar system and George Washington’s Mount Vernon, as well as symbolic portrayals of stories from Buddhist scripture, such as the use of the lotus to convey enlightenment or the sailing ship that carries one across the sea of suffering to the other side, or towards nirvana.”

These changes prompted Arin to adopt Khrua In Khong’s mural paintings as the inspiration for his most recent solo exhibition.

“I think it’s incredibly interesting how rulers have utilized languages and writings to brainwash and change people’s beliefs and move an entire society into a different shape and form.”

In “We will leave and never return,” Arin chose to exhibit works made entirely of earthy materials in the gallery’s first room. It was a return that permitted us to travel back in time to the period of animism, when people first began to create fiction. While all of the artworks in this area are made of earthen materials, they are arranged in various patterns. Each design represents a “journey of spiritual collective consciousness” that has evolved in the post-animist world.

Firstly, the white wax painting with an octagonal shape made of white threads fixed with brass pins inside a circular shape. The octagon is a symbol used by numerous cults and faiths, including Christianity, Judaism, and Taoism, to symbolize reincarnation. Similarly, in the Renaissance, the octagonal shape indicates a reexamination of the preexisting definitions of humans. Another abstract piece appears in the form of a big painting made of incense powder (the scent filling the room actually originated from this particular artwork). The painting is the same size as Khrua In Khong’s lotus painting. Arin simply removed all the figures and stories this time, leaving only the brass lines marking the perspective at the bottom of the picture. The lines depict the next stage of humanity’s spiritual collective consciousness journey, in which humans denied God and concentrated more on their own individuality.

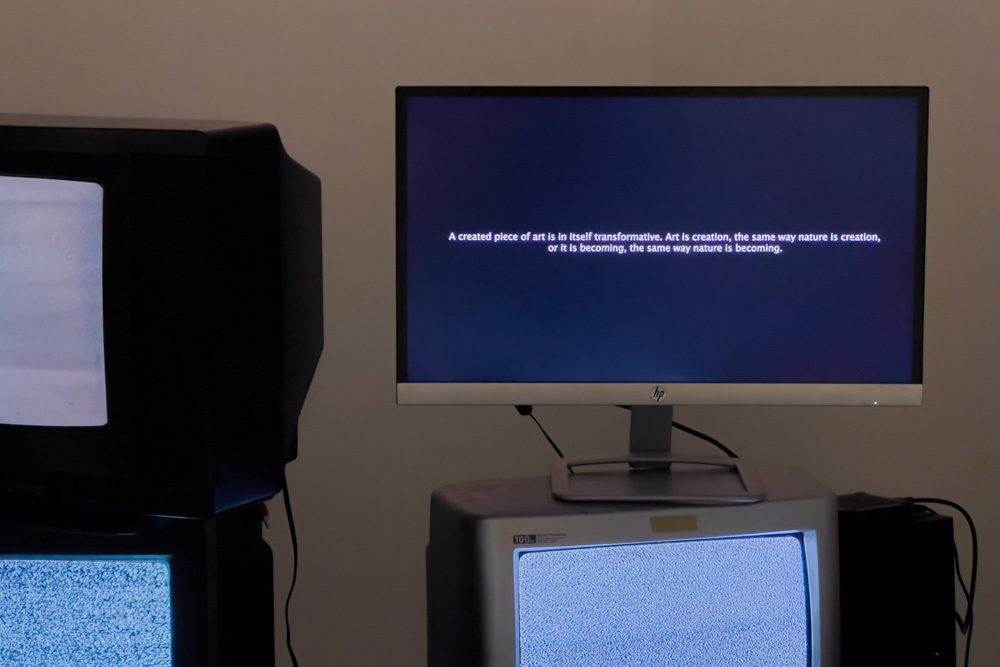

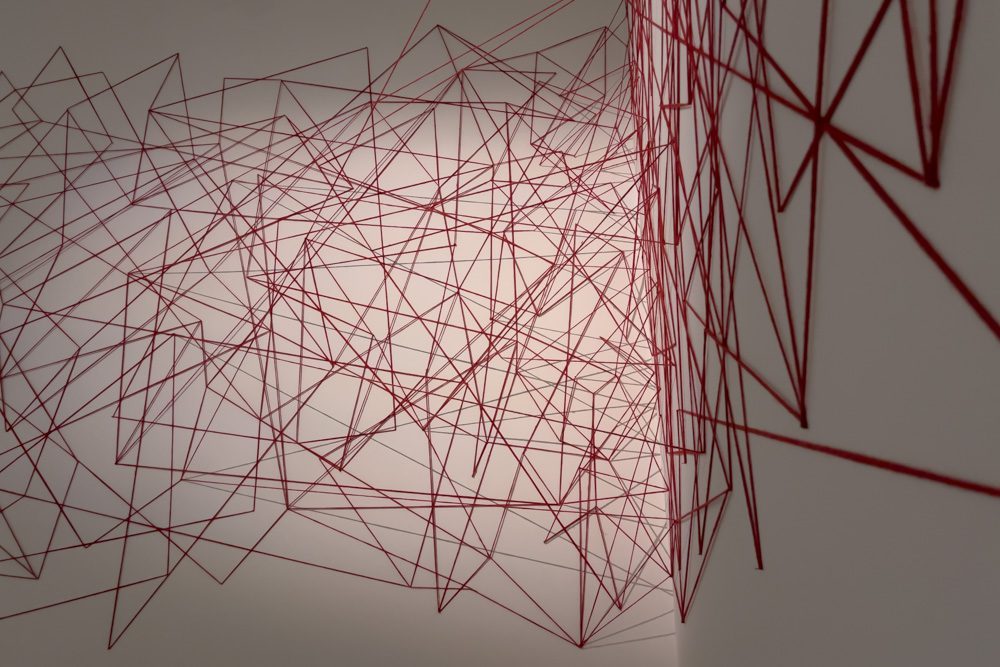

Such transformation was reflected in the installation piece, in which several television and computer screens displayed various moving images with the sound of a woman reading the artist’s message. Holy threads dyed in crimson were hung in an intertwined web in one of the room’s corners, forming a geometric pattern. Arin represents the Cartesian Coordinate System with these threads. “The Cartesian Coordinate System, or the X and Y axes, is another pattern that humans invented. It has been used to calculate the time and space of the entire planet, such as separating time zones, creating a world map, or calculating the position of a satellite, among other things. Axes are hypothetical. They don’t exist, but they were utilized to help justify the modern world. In this day and age, our collective consciousness is no longer contained in any earth material. It’s rather about seeing the truth that is moving as opposed to the truth that is depicted on a painting. All the contents on the screens have been turned into the truth; however, what we see on the screen isn’t the full truth. There are innumerable things that exist outside of the screen.

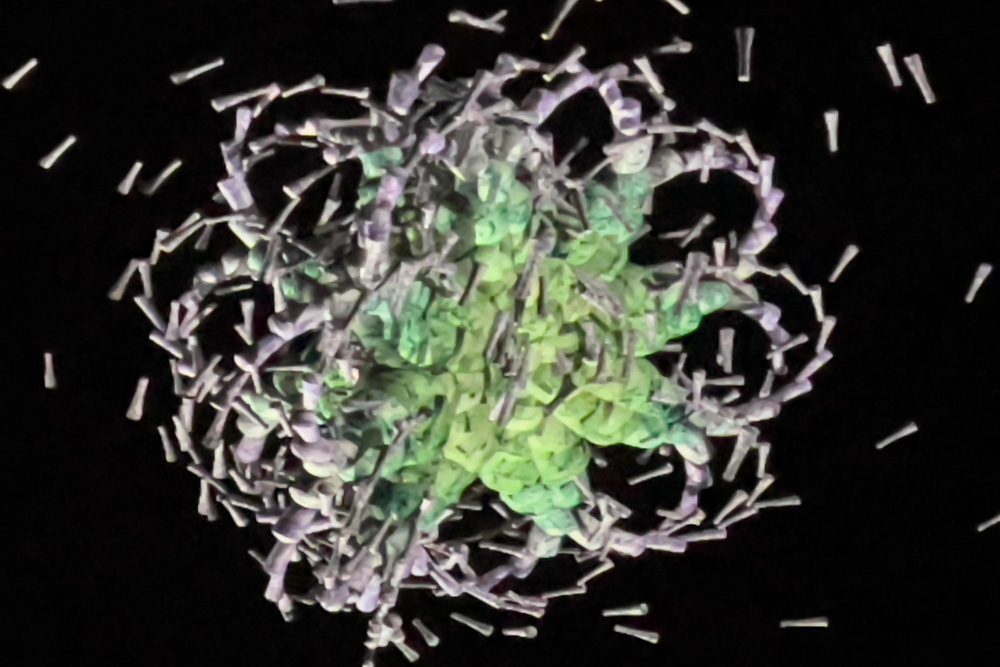

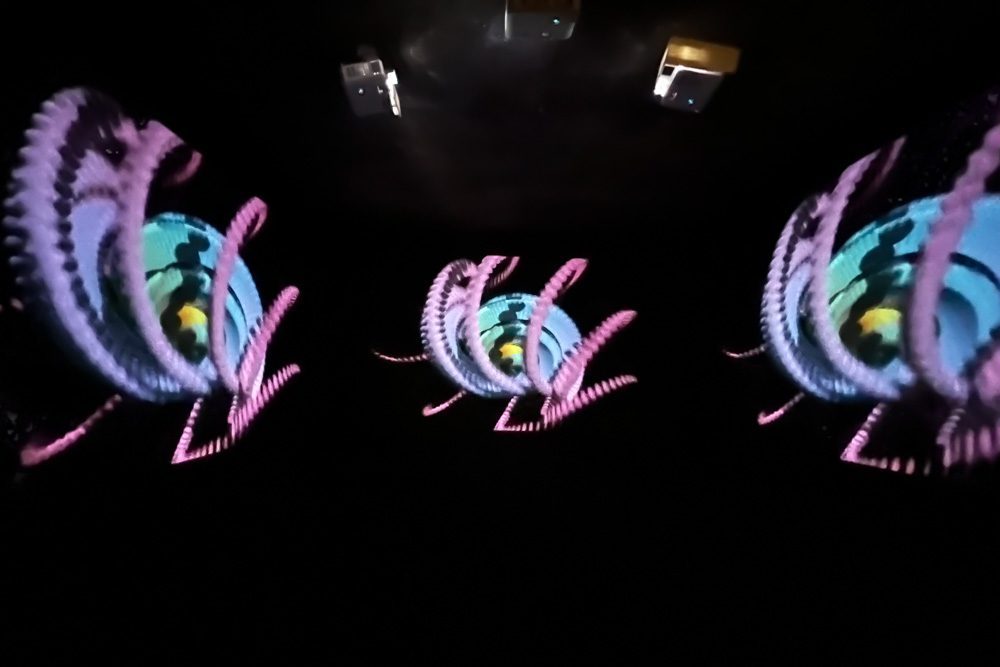

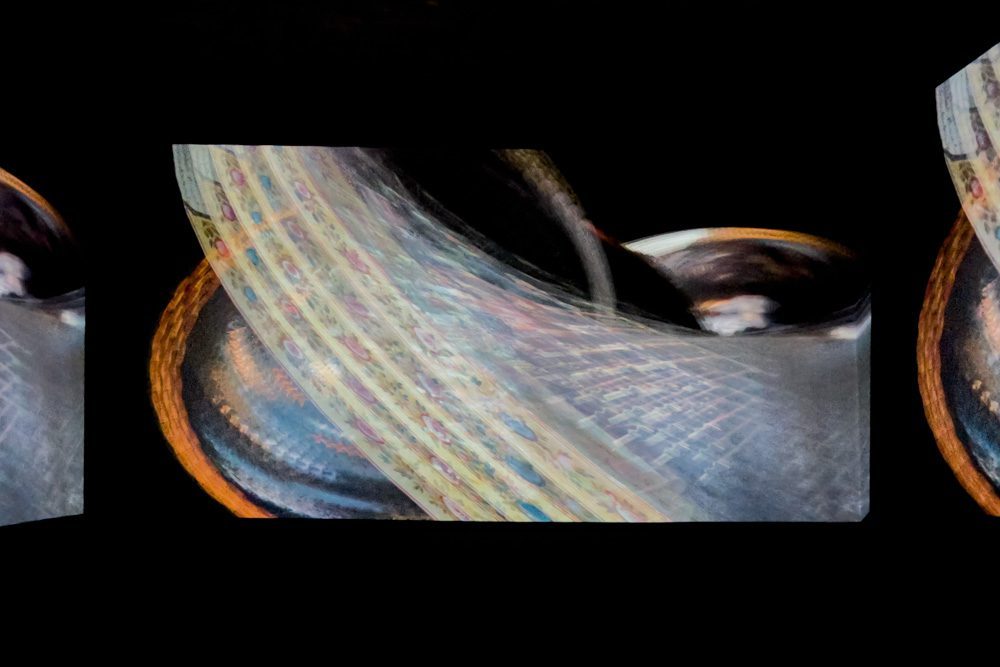

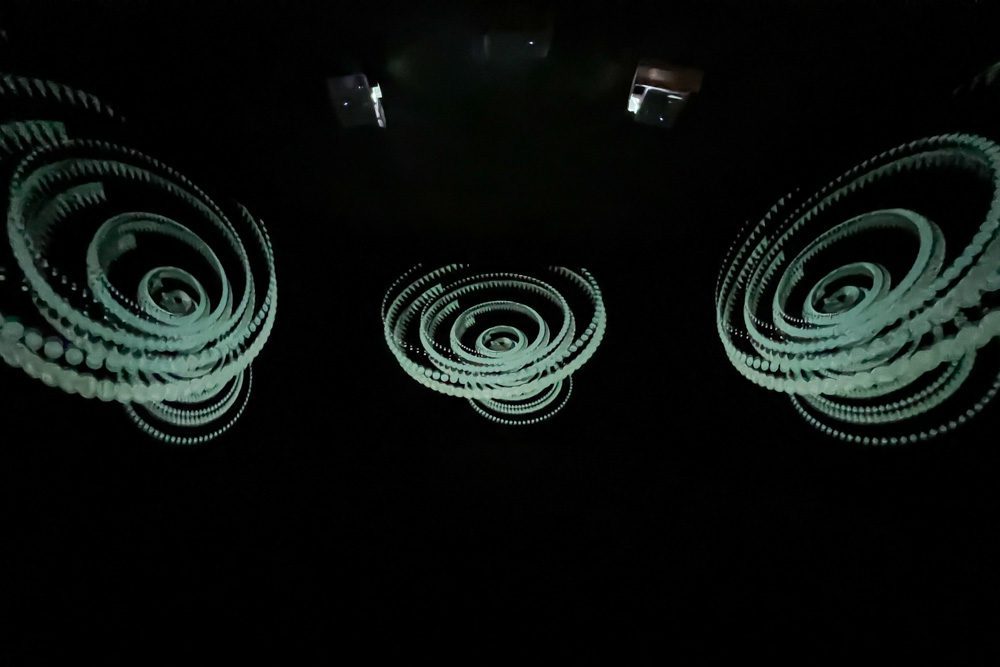

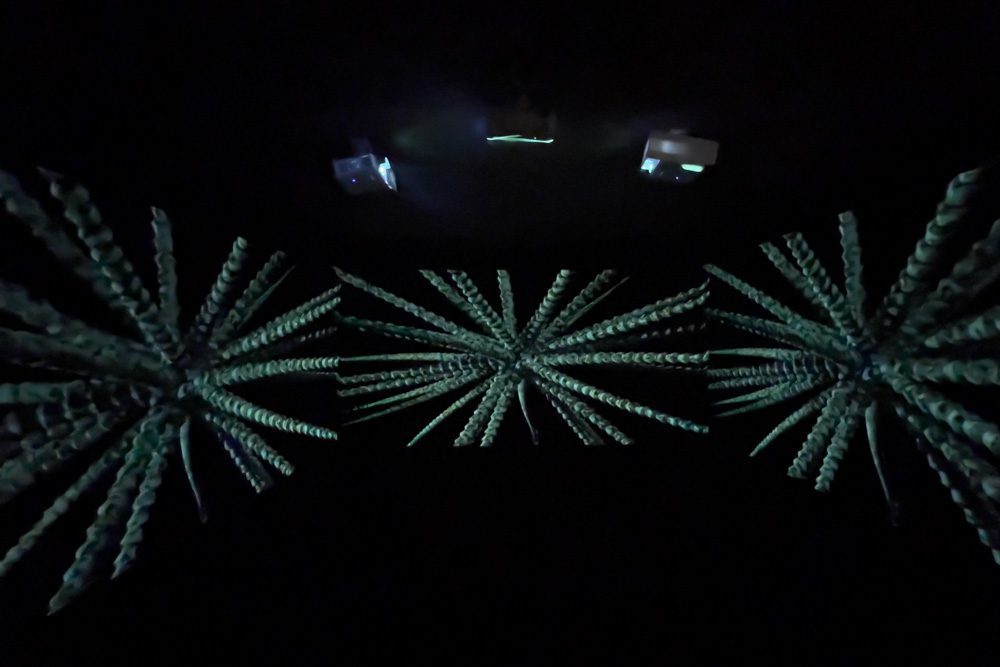

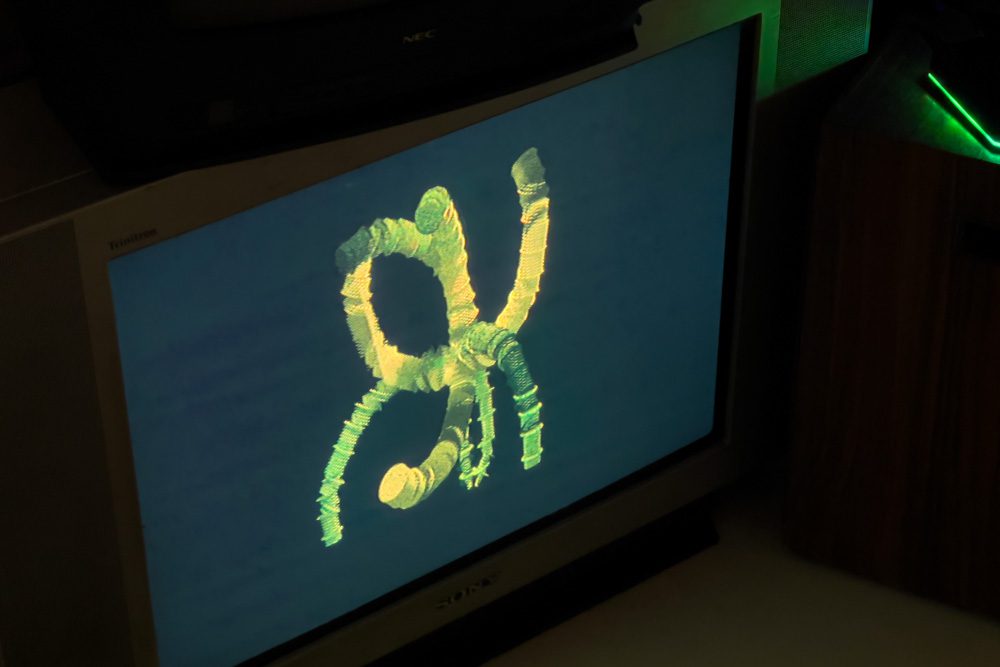

“You can see from all of this that power is in the text. Nevertheless, the text changes and varies depending on the time period. Text or fiction is now the property of large corporations that create this virtual space for individuals to tell their own stories.” Arin was discussing the animation in the dark room, where he digitalized Khrua In Khong’s painting. An algorithm is used to generate three-dimensional possibilities from Khrua In Khong’s painting. Arin collaborated on this piece with 3D artist Deenair Tantivejakul and sound artist Nuttapon Sawasdee. “I asked the sound artist to record the sound of water rushing beneath the main hall of Wat Boromniwat Ratworawihan Temple, where Khrua In Khong’s paintings are located, as well as the sounds of monks chanting and ambient sounds inside the main hall. Everything was mixed together to create this distinct sound. I then asked the 3D artist to employ two types of form, geometric and biological, as the base of the algorithm, in order to find alternative possibilities of transforming the forms in Khrua In Khong’s artwork into different shapes.”

The exhibition concludes with a sculpture consisting of many long strips hanging from the ceiling in the center of the exhibition room. These long strips, which have the same length as Khrua In Khong’s mural painting, were made of rubber, a product of a common economic crop growing in Southeast Asia that was produced solely to be shipped and used as a raw material in the industrial sector of western countries. Arin folded each rubber strip into a Mobius strip with a single-sided surface and edge. By removing the barrier between the interior and exterior of a Mobius strip, the shape conveys the continuity of spaces on the same plane. Arin could also intend to portray the connection between “fiction” that has been turned into “non-fiction” and how it has influenced the way we live to the point that fiction and reality have become indistinguishable.

“As an artist, I think it is important for me to comprehend the factors that have caused human society to transform into what it is now,” Arin said about the motivation for this solo exhibition. “These days, fictions are specific, yet they are linked to a larger society. The shape of the virtual world, which is simply an attempt to integrate the entire planet into one unified universe, is one of the notions that has become increasingly prominent. However, what I find troublesome in such an endeavor are the inherent conflicts of a society that is falling apart…there is an ongoing internal culture war that is escalating.”

When asked if it is possible for people to break free from the influences of fictions, Arin replied that it is probably impossible, but rather we should find the fiction that is the most fitting for today’s society. “We’ve advanced in various domains of knowledge, allowing us to better understand things. Going back in time and revisiting the stories of when we were still a part of nature could be a good thing. It was during this period that our consciousness and spirit became one with everything on this planet. Trying to understand them today isn’t an attempt to build yet another superhuman character, but rather to find a way to minimize our individuality and become more interconnected with other things than we have been.

“To truly be free of fictions, however, it would be entering the stage of nirvana,” Arin added, laughing, using a word whose meaning is very similar to the title of his exhibition.

“We will leave and never return” by Arin Rungjang will be showcased at Gallery VER until December 25th, 2022, 12.00–18.00. (Closed on Mondays and Tuesdays)