A YELLOW SUBMARINE COFFEE TANK’S EXTENSION OFFERS NO SPECIFIC FUNCTION NOR EXPLICIT BOUNDARY, JUST THE SPACE BETWEEN THE CONCRETE PLANE AND GEOGRAPHICAL CONCEIVED FROM THE ATTEMPT TO EXPLORE THE PHENOMENON THAT COULD HAPPEN UNDER THE ROOF STRUCTURE BESIDES DRINKING COFFEE

TEXT: KORRAKOT LORDKAM

PHOTO: BEER SINGNOI

(For Thai, press here)

It has been years since Yellow Submarine Coffee Tank took over a piece of sloped terrain on a vast agricultural land in Pak Chong district of Thailand’s Nakhon Ratchasima province. The architecture of Yellow Submarine both surrounds and fits into the growing forest of mountain cedars, making it one of the most unique-looking cafes in the area when it first opened. The café’s extension, dubbed Yellow Mini, which was planned shortly after the project’s completion, has recently been unveiled. The architectural concept complements and interacts with the surrounding landscape, just like the first building did. The difference, though, lies in the utilization of architectural features and the user experience that the new addition seeks to deliver—something that is more open and possibly more ambiguous than its predecessor.

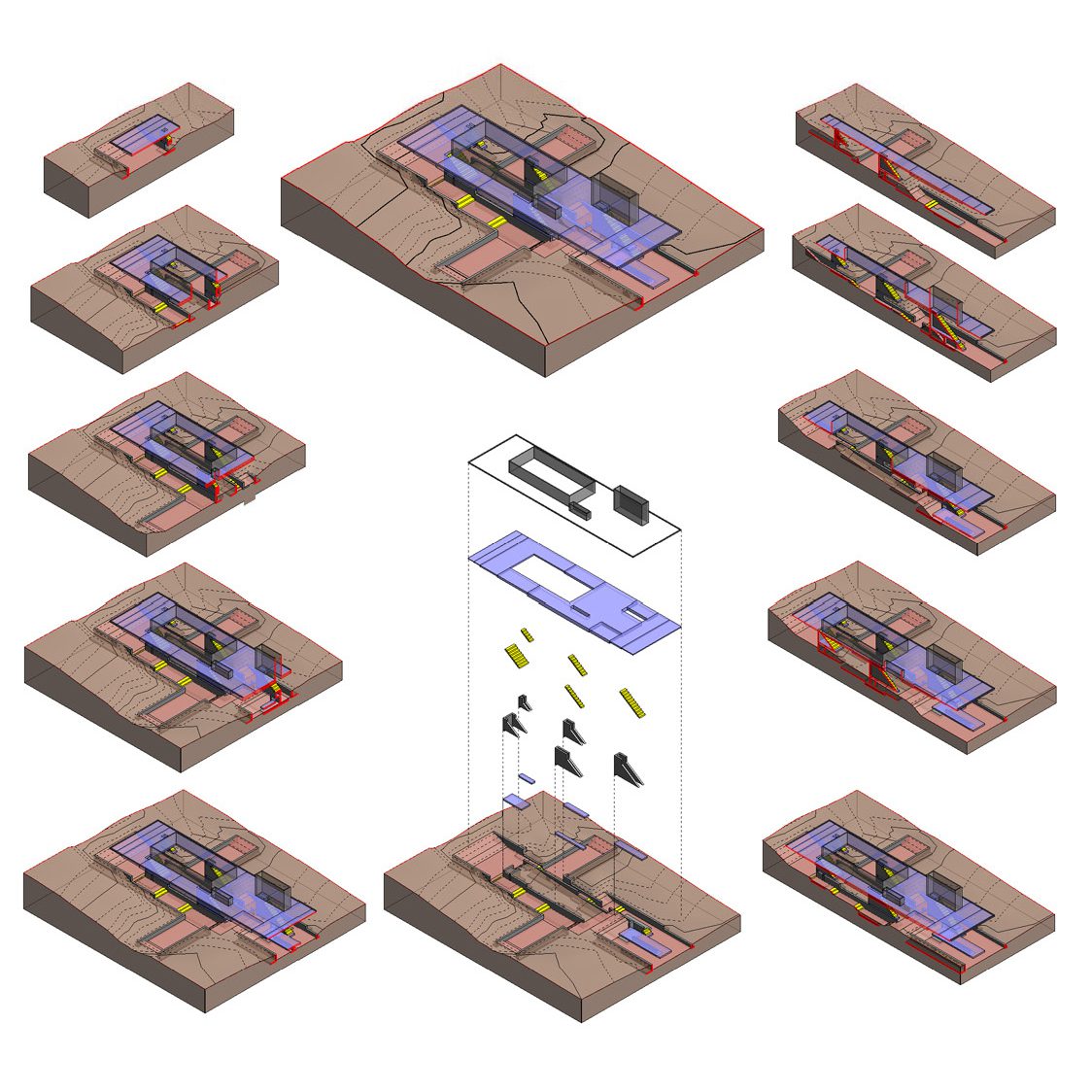

Suebsai Jittakasem, Prasert Ananthayanont, and Nutt La-iad-on of JOYS Architects, the design team behind Yellow Mini, were also the members of the architecture team who oversaw the design of Yellow Submarine Coffee Tank. They explained how Yellow Submarine planned to reach a new business goal by increasing the number of seats and functional area while remaining true to the previous concept and context. To attract both new and returning customers, the new addition would need to be fresh and appealing. And to achieve the desired result, the design plays with architectural components drawn from the site to create memorable user experiences that both projects share despite the differences in design elements.

“With Yellow Submarine, we added what would become the most prominent component of the architecture, which is the walls,” Suebsai recounted the starting point of the project’s design concept.

“You can think of them as two vertical planes that were buried into the ground and enable us to grasp the physical properties of the site – which is the slope. As a result, its presence is enhanced by the addition of the walls. We wanted to keep this approach with the new Yellow Submarine by essentially accentuating the site’s inclination.”

The first project’s attempt to highlight the location’s geographical characteristics is much more noticeable. The walls on the two sides of the first Yellow Submarine established a boundary between the interior and outdoors, producing a space with a strong sense of enclosure. Instead of looking out into the outside view, these walls end up generating architecture that entices users to pay attention to interior components such as the trees, the shades, the people and drinks that are being served, as well as the different ground levels they’re standing on.

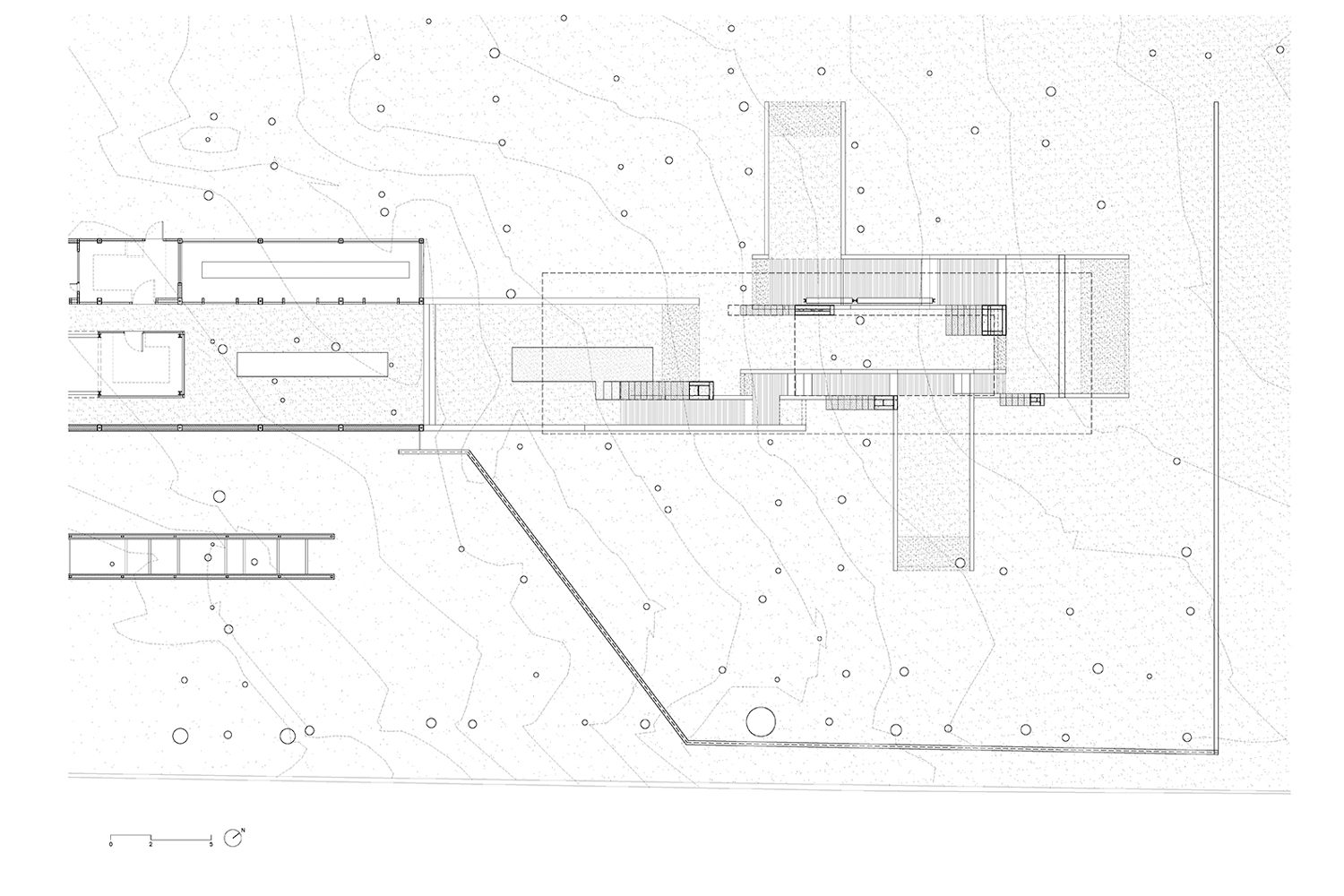

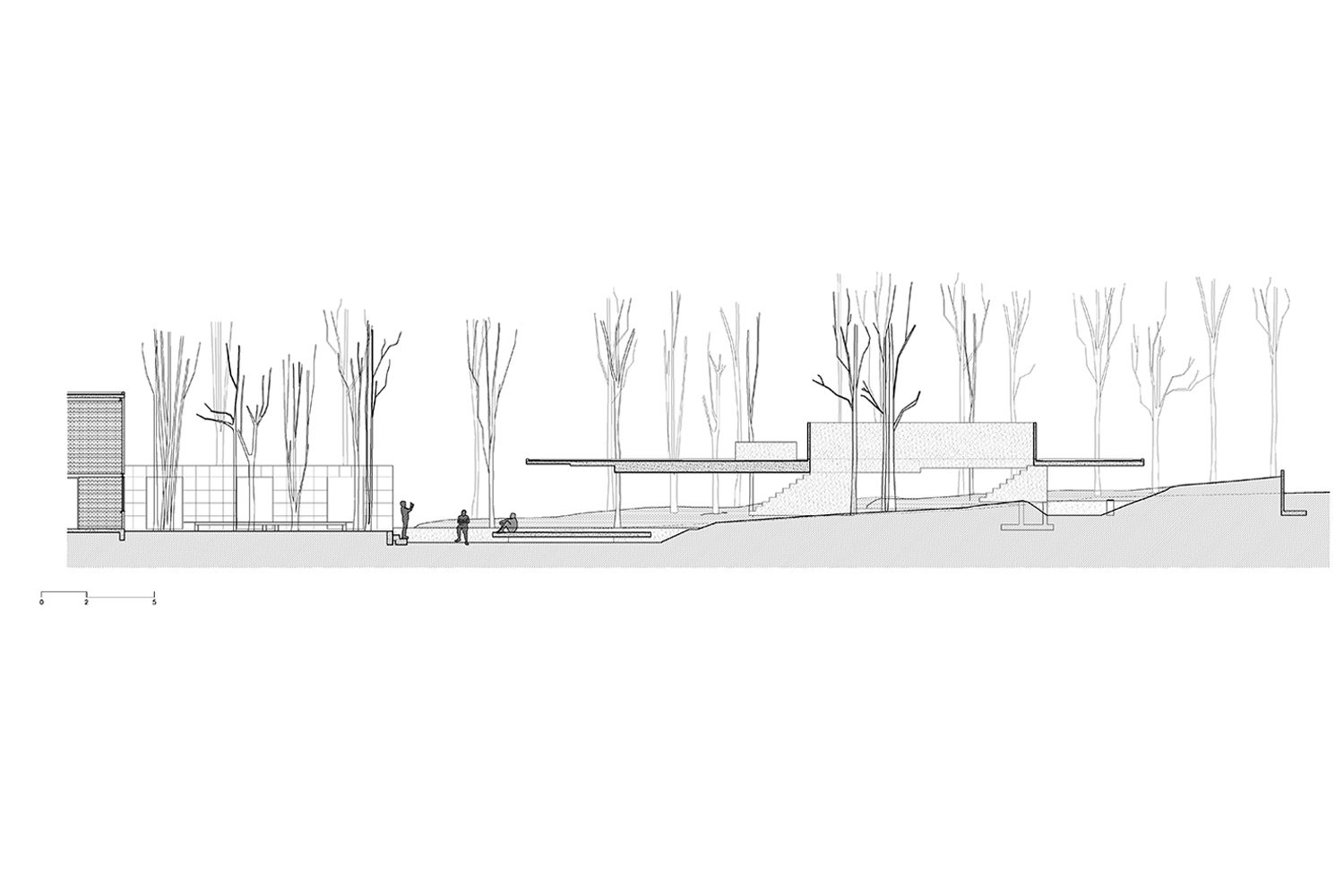

The architects detailed their objective for the new project, which was to adopt a similar approach to design but with a different focus on producing diverse experiences and focusing on ways things can be interpreted by referencing the variations of the ground’s sloping levels. The effective method devised for this purpose was to use a large overhead horizontal plane to define the boundaries of the site as well as the functional spaces, rather than using vertical planes to form the enclosure as they did in the first project.

The considerable mass of the roof is intentionally meant to be higher than the slope, which ascends from the preexisting building on the right. To establish a sense of connectivity, the roof is aligned to be the same height as the first building. The slope in this area creates a void beneath the roof with differing heights, with the highest point being as high as 3.5 meters, while the lowest position is so low that it doesn’t offer any functional space. The design then takes into account the structure that will support the weight of the horizontal plane. At this stage, engineering possibilities significantly contributed to how the architectural structure and space could be expressed. The building’s five designated weight-bearing points are in alternate locations that ascend to varying locations of the slope, allowing the 8 x 27-meter mass of the roof to showcase itself without being confined by any definite boundary. The structure is built to resemble a flight of stairs, which corresponds to the land’s inclining features. The collaboration between the design team and the engineers resulted in another distinguishing feature in which the thickness of the concrete roof gradually grows thinner, particularly at the roof’s farthest end, thereby lessening the weight that the structure has to bear due to the extended protrusion. The architecture team emphasized how well the structural integrity represents the reality of engineering possibilities.

Structural System

The architects went on to explain how the functional spaces are determined in relation to the different parts of the foundation, with each location planned to be particularly expansive in order to support the weight of the concrete roof, whose greatest projection range is almost 10 meters. The seating areas are determined by the perimeters of these foundation members, which were expanded and managed differently. There is a section where the ground is flattened and encircled by concrete members that can be used as seating areas, or where large concrete slabs are built to have the additional function of a massive table. These areas are manipulated in relation to the space below the roof, whose shifting heights are dictated by the varying heights of the sloping ground, particularly the section where the gap between the overhead plane and the floor become the closest. The roof has been gauged out into a void, allowing users to walk up the slope and continue to use the space. However, the functions stored within the addition are intended to be very loosely connected and undefined. “The most striking architectural expression of the project is the roof,” remarked Prasert, one of the project’s architects. The mass exhibits density and solidity, as well as its existence as substantial, tangible matter. But, because there is a functional requirement that there be space for people to sit down and enjoy their coffee, we agreed to avoid using tables or anything that would be too obvious. As we played around with the ideas we would use with the slope, we tried to imagine other activities that could happen in the spaces under the roof structure besides drinking coffee.”

Following the design team’s intention, all of the aforementioned architectural and structural components were presented with their concrete surfaces entirely exposed. While the decision was taken in part due to the limited budget, it was also made with the purpose of preserving the project’s architectural direction, which focuses on the most straightforward and natural design process, construction, and final appearance. In other words, the primary intent behind the overhead plane was for its mass to serve as the starting point for what would succeed, as the architects observed and directed the design to follow the natural evolving course of the project without having to give any specific or definite meaning to what or how things should be. The essence of this place has, therefore, evolved along the way as things progressed organically rather than as a result of a predetermined route and destination.

It resonates with what Nutt, another member of the design team, explained: “We had this incredibly good original structure, so when we were working out how the addition would come to be, we constantly had this fear about whether the new building would wind up damaging the old one. “As a result, there were constant discussions and questions within the team about where the true boundary lies between this place being a building and something that isn’t a building.

“We believe that is what keeps the structure from becoming static. Because there is no predefined boundary for the space to be inside or beneath a structure. The architectural spaces are constantly changing. They flow outdoors and sometimes return inside. It could be one of the things that gives this piece of architecture its metaphorical movement and continually shifting energy.”

The movement that the architecture team mentioned is one of the characteristics that uniquely differentiates the architecture of Yellow Mini from the original building. While the two projects were created from abstract vertical planes that formed a boundary, the enclosure of the first building created an obvious, well-defined boundary with a meticulously curated ambiance and components out of certain limitations and requirements, before presenting them as a memorable user experience. On the other hand, the new addition contains physical characteristics that are more open, while the functional purposes and spatial experiences are more indefinite and offer more freedom. The boundary that has been established is barely there and can be moved around by users’ varying presences and interactions. Meanwhile, the environment, functions, and people’s connections with the architecture exist beyond the definitive and immutable possession of any spatial boundaries or constraints.