THE BOOK BY JULIA WATSON GUIDES READERS THROUGH AN EXPLORATION OF THE MYTHOLOGIES OF INDIGENOUS TRIBES WITH A SYMBIOTIC RELATIONSHIP WITH NATURE, AND HOW THIS RELATIONSHIP REFLECTS THEIR EVERYDAY OBJECTS AND BUILDINGS DESIGN

TEXT: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUL

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Julia Watson

Taschen America Llc (2020)

Hardcover

10 x 0.98 x 6.89 inches

418 pages

ISBN 978-383-657-818-9

The narrative of the past has propelled humanity forward. Locally derived legends give rise to sets of ideas and beliefs that a civilization adopts and fosters as its culture. They shape norms, traditions, and practices, creating perspectives through which any nation perceives its environment. These stories resemble scattered waterways, sometimes converging harmoniously, while others dry up and disappear. Unfortunately, some narratives are intentionally discarded, perceived as too outdated to align with the contemporary world driven by scientific and informational advancements. Meanwhile, the mainstream narrative shifts towards a new storytelling concept known as the ‘Mythology of Technology,’ placing emphasis on inventions or innovations that surpass human or natural limitations. This coincides with the era of the ‘Anthropocene,’ signifying the period in which humans intentionally or unintentionally became the most influential life forms, significantly impacting nature. In the time of global warming, rising ocean temperatures, and the extinction of various species, humanity questions mainstream narratives and myths guiding its existence. This encourages the exploration of new narratives that allow both humanity and nature to coexist. The intriguing aspect is that the solutions offered by this new mythology may not be hidden too far back in the past that we’ve experienced.

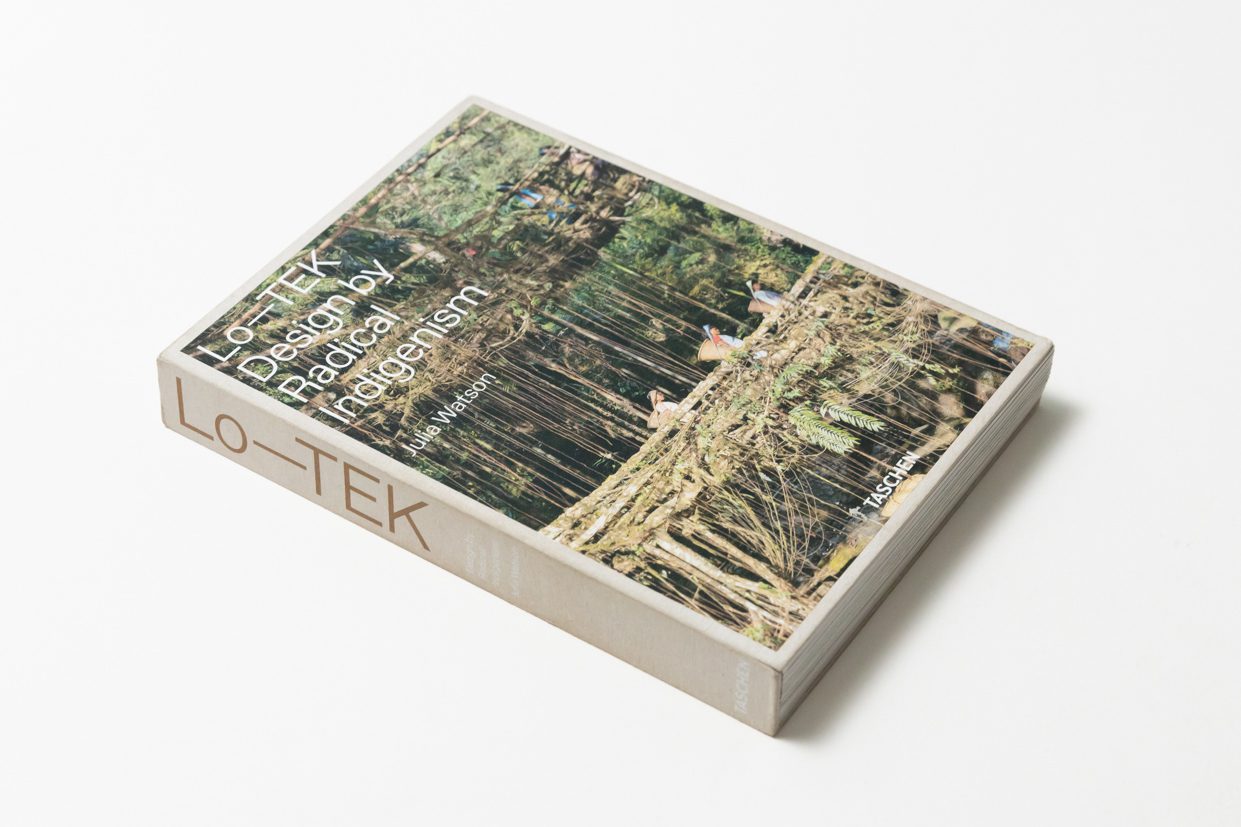

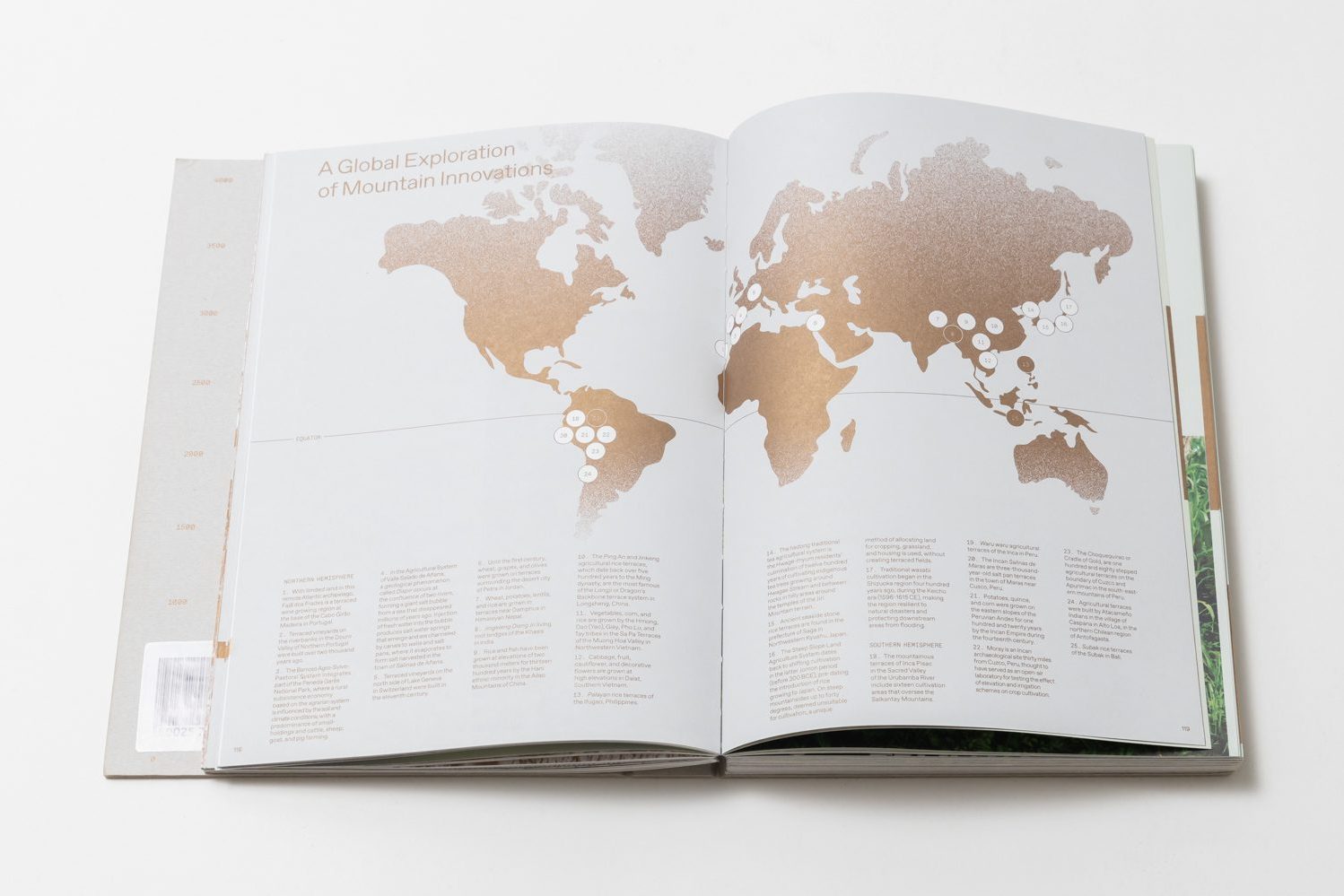

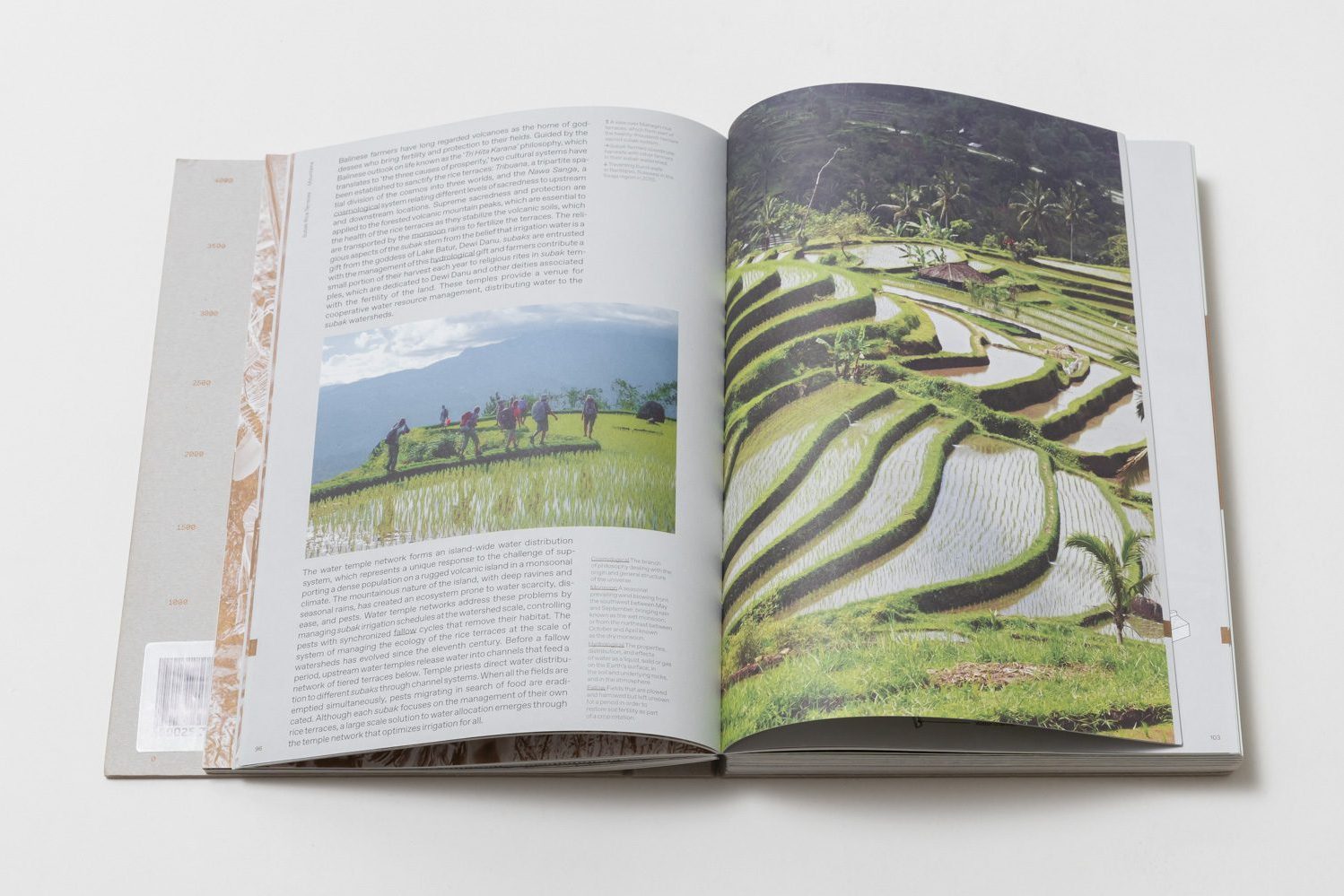

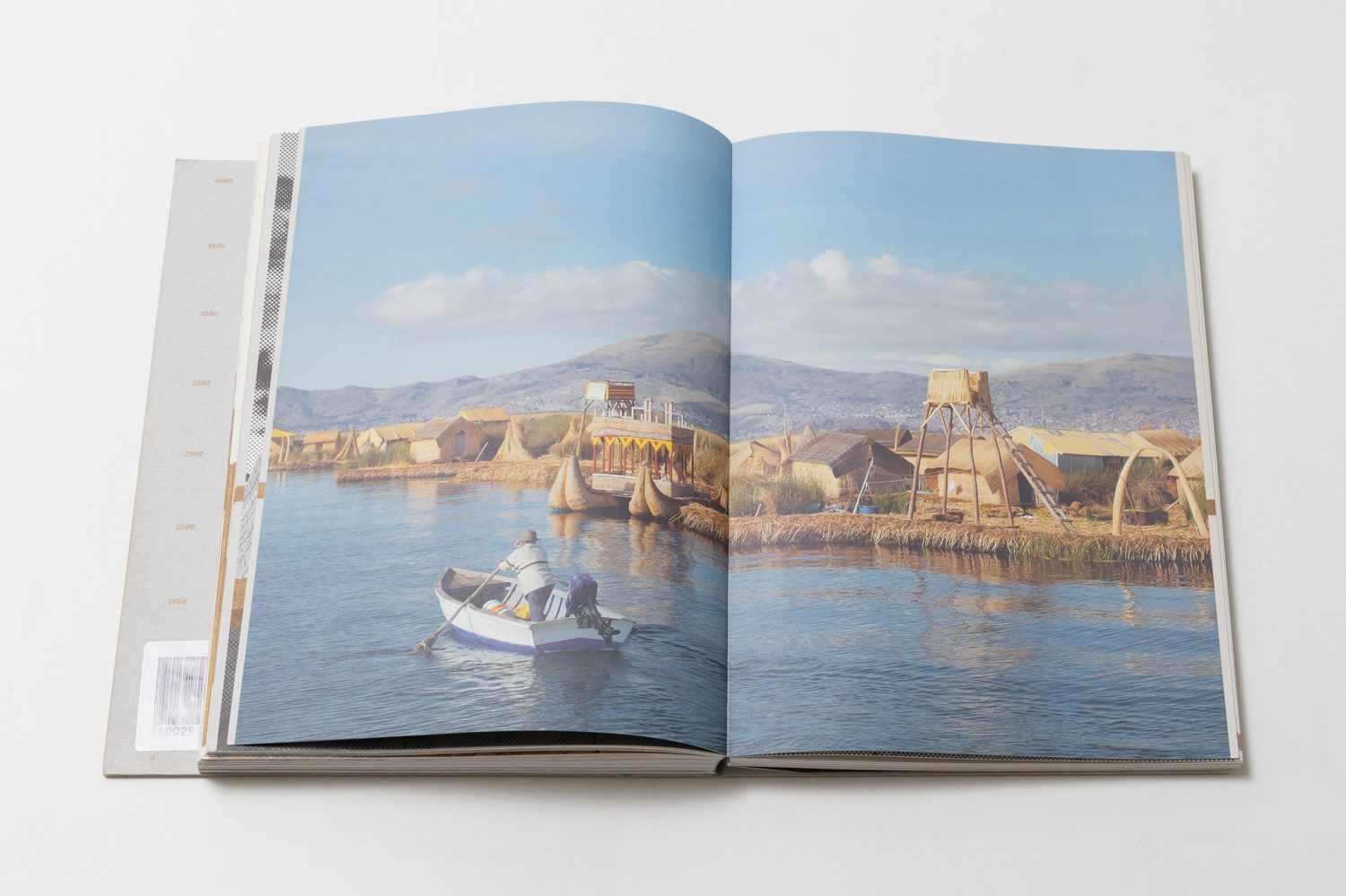

‘Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism’ is a book by Julia Watson, a writer, researcher, and landscape architect who established Julia Watson Studio in New York. The book guides readers through an exploration of the ‘mythologies’ of indigenous tribes and cultures, and how they have shaped these people’s relationships with the environment and influenced the development of spatial technologies and architecture. The book introduces the concept of ‘Lo—TEK,’ an abbreviation for (Lo)cal + (T)raditional (E)cological (K)nowledge – a thought process that advocates for incorporating indigenous local technologies into contemporary architecture and design to foster a symbiotic relationship between humans and nature. The content of the book delves into technologies and their origins, illustrating how they evolved from the legends and mythologies of 18 tribes scattered globally across four ecological systems: mountains, forests, deserts, and watershed areas. These systems possess unique physical contexts that contribute to the diverse landscapes of the regions they inhabit.

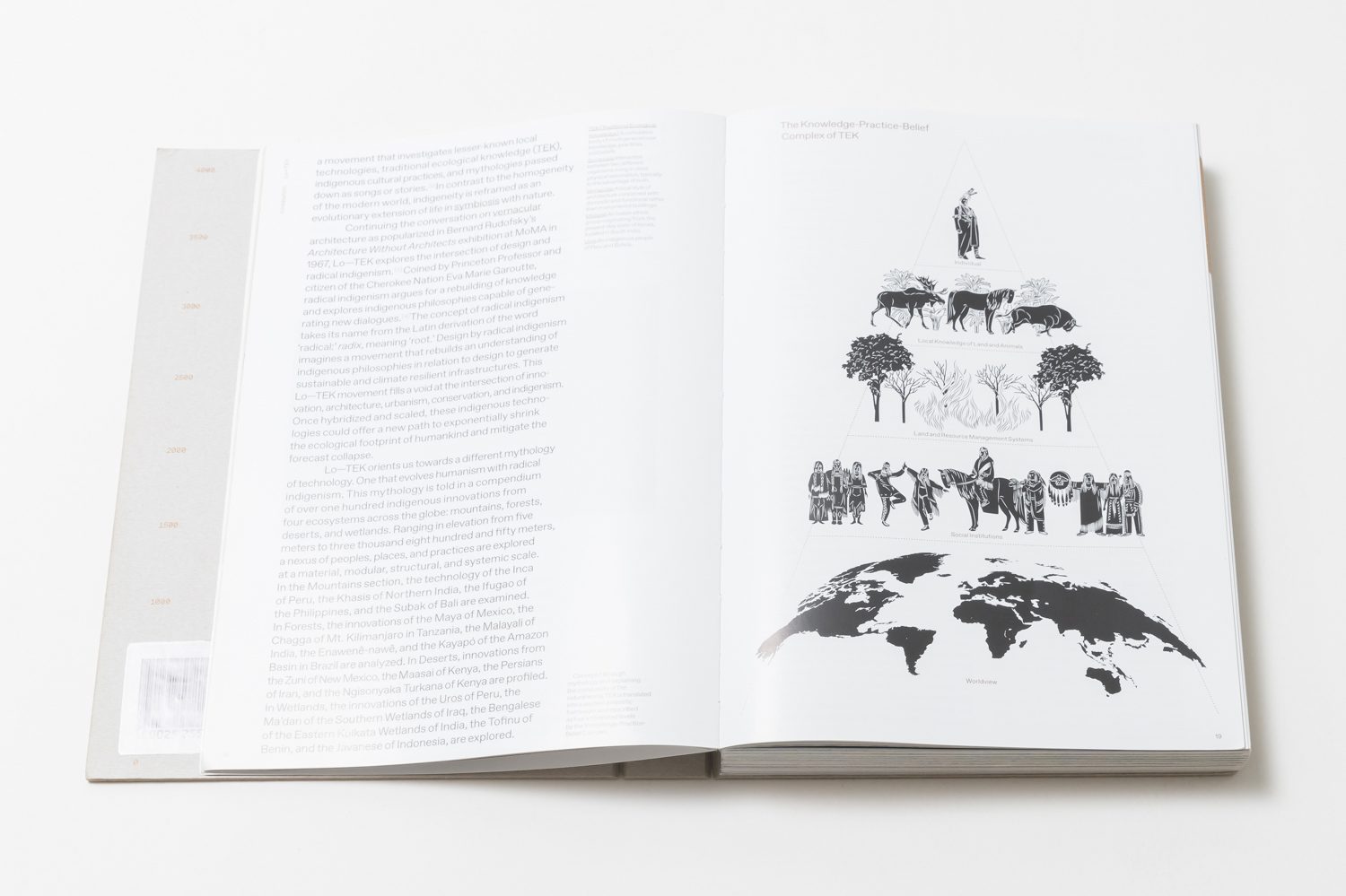

Julia starts off the book by pointing out how different bodies of knowledge of indigenous tribes have evolved through processes of trial and error, before they have been passed down through various forms of discourse such as rituals, folktales, and myths. These narratives become ingrained in the practices and ways of living within communities, giving rise to specific bodies of knowledge deeply rooted and profoundly attuned to the local environment and climate.

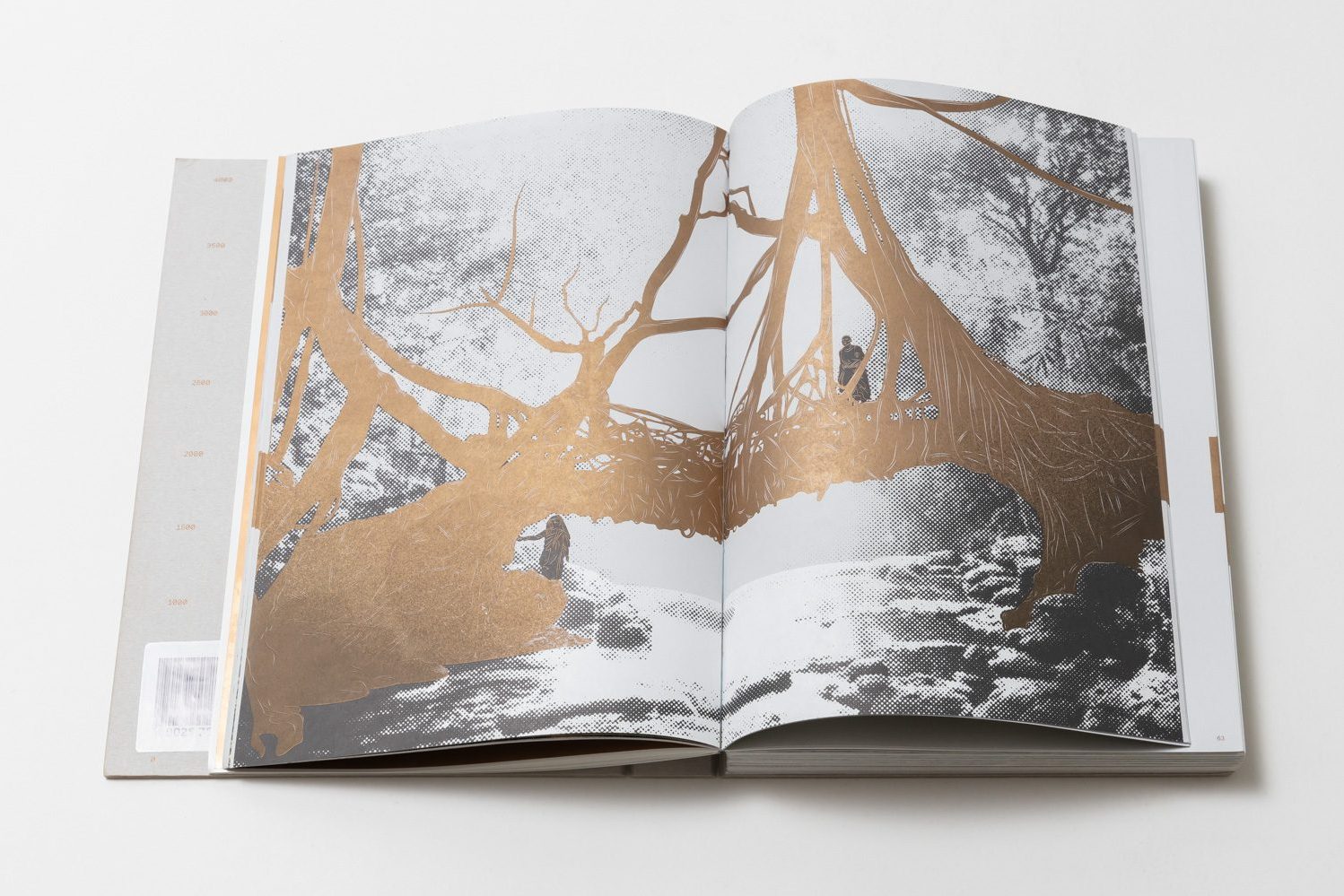

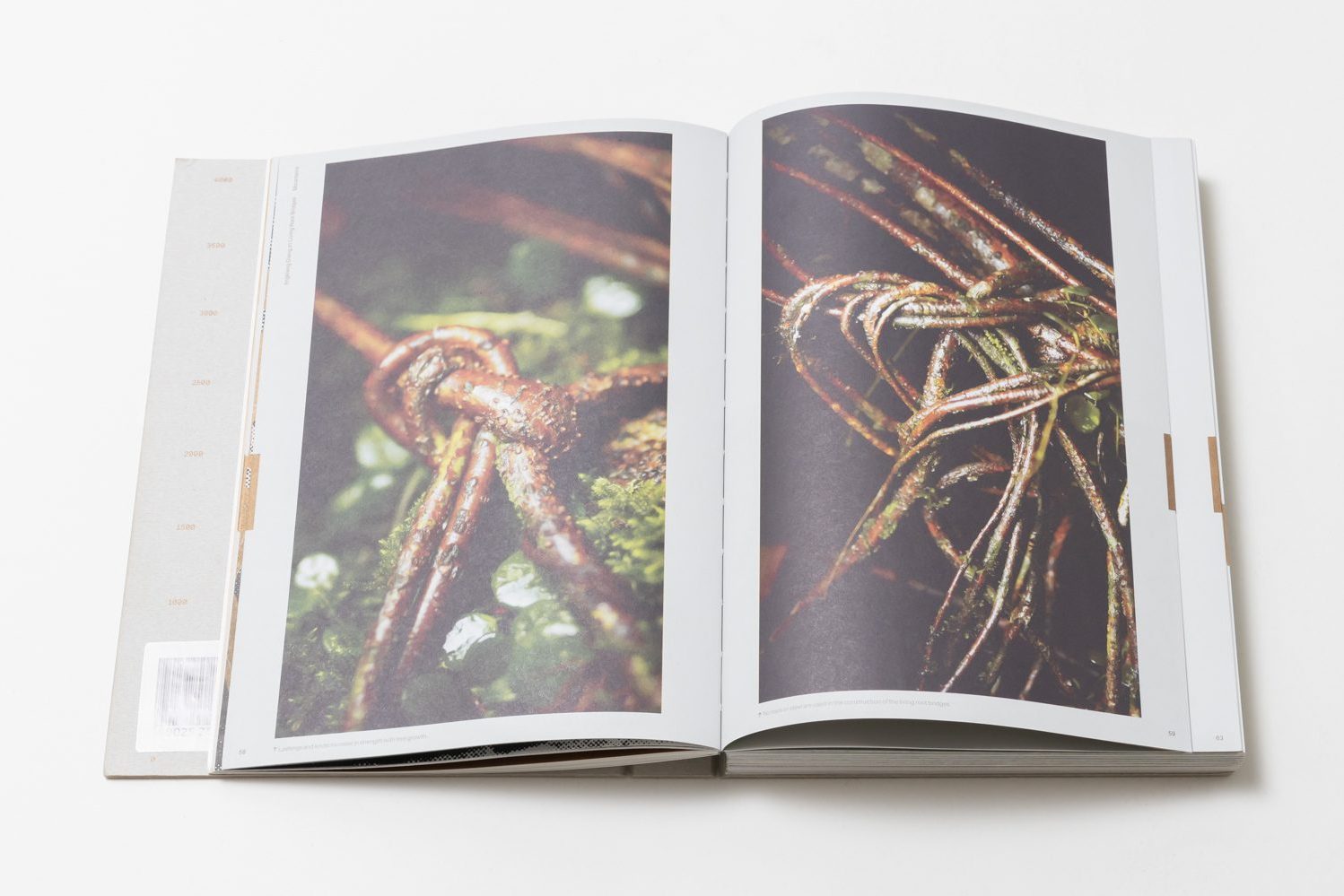

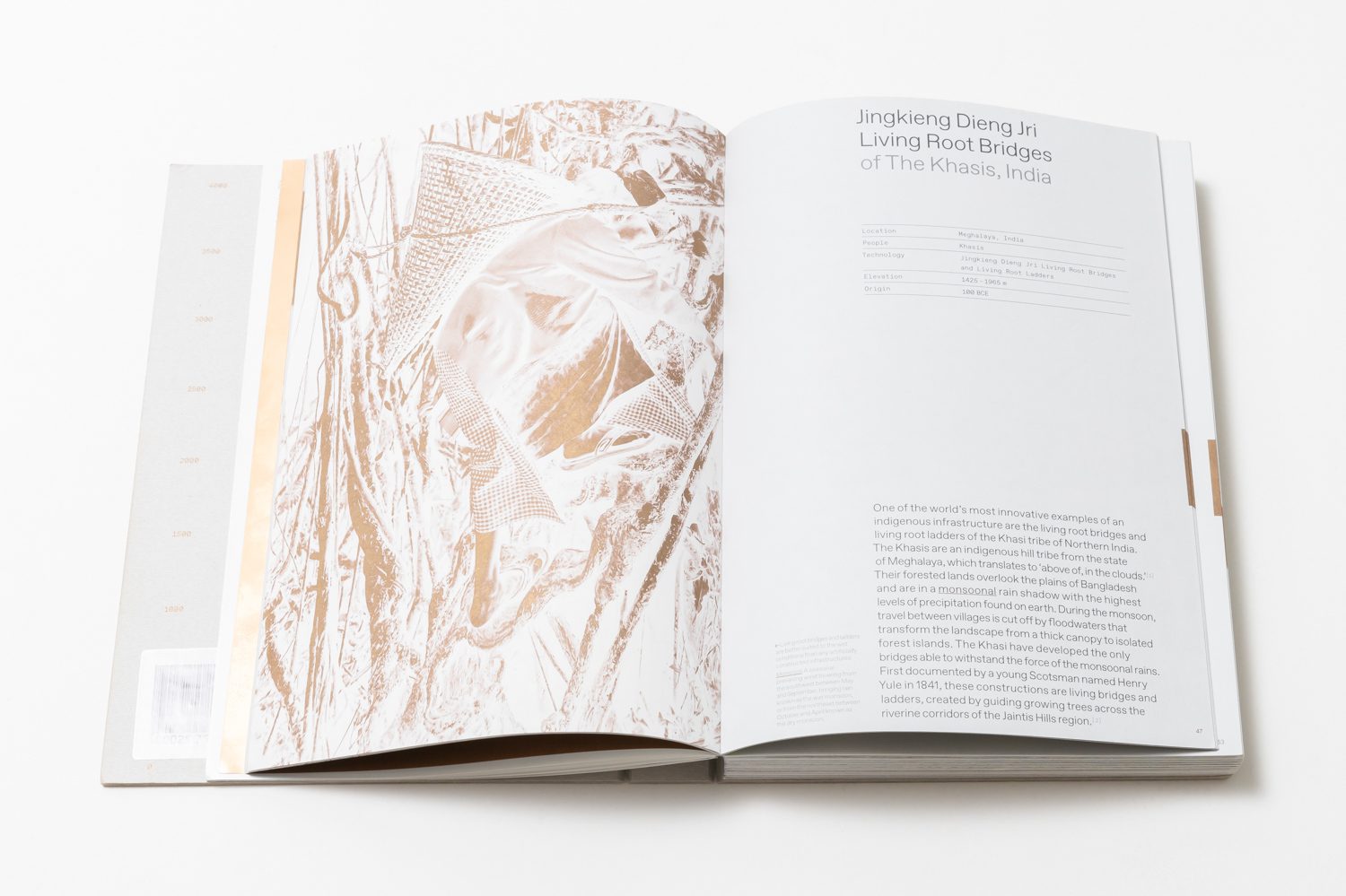

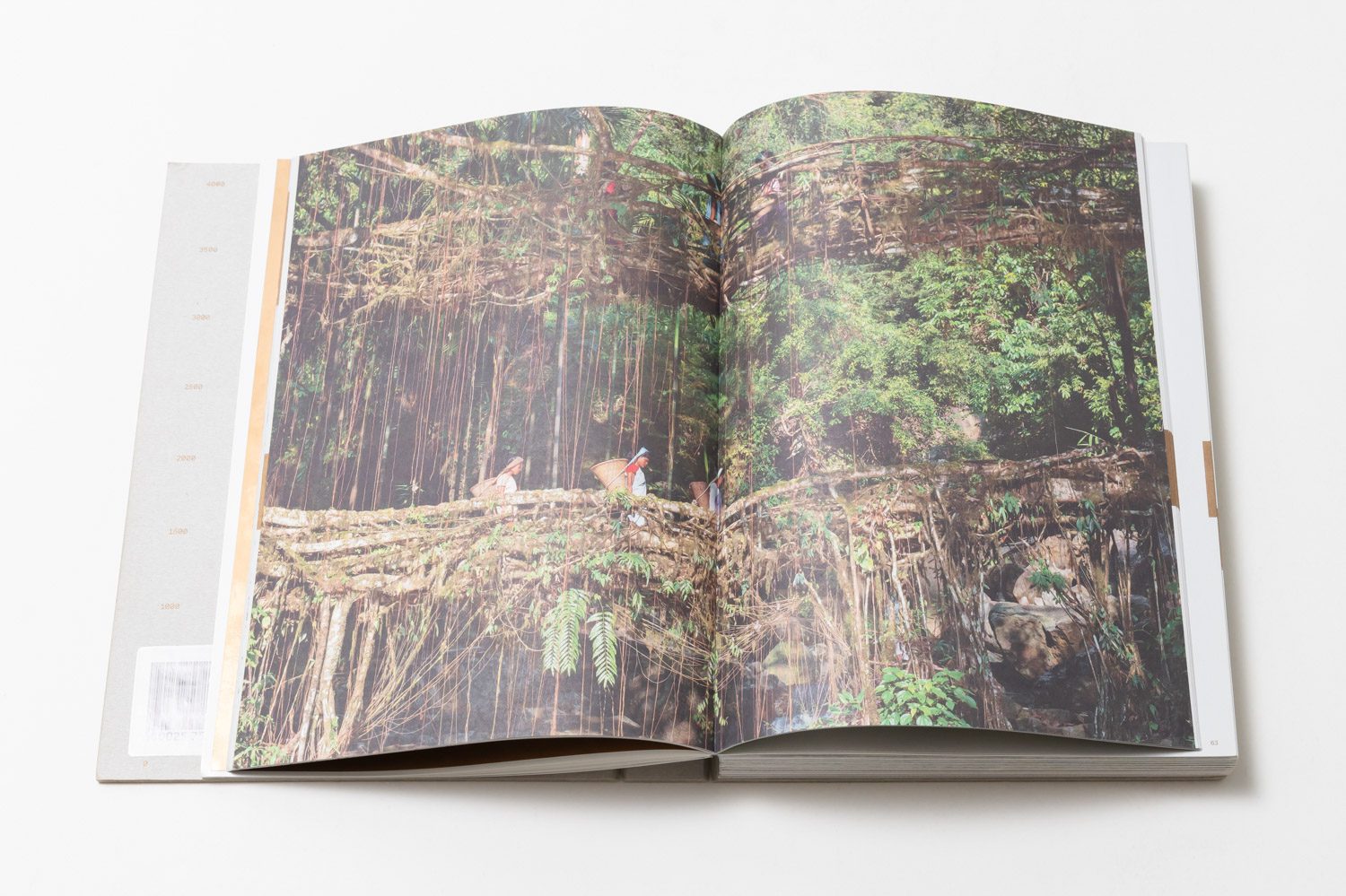

An illustrative example comes from the Khasis, a tribal community in the Meghalaya region of northern India. They have ingeniously constructed bridges across rivers using the Indian rubber fig tree. This construction can be traced back to an ancient legend about the journey of their ancestors who descended from heaven to this land, crossing a sacred tree-shaped bridge. During the monsoon season, the Khasis utilize the Indian rubber fig tree bridge to travel between both sides of the bank, often separated by the high-water level. The construction of the tree bridge begins with the planting of Indian rubber fig trees on both sides of the bank. Trunks are then placed between the two sides, allowing the roots of the rubber fig trees to gradually grow and securely hold the trunks together, forming a robust bridge.

This meticulous process, taking approximately 50 years, results in a bridge strengthened by intertwined roots, providing not only resilience against severe storms but also obtains continuous reinforcement over time. The bridge-building technique reflects the wisdom and commitment of the Khasis that aligns with sustainability. It is evident in their use of species that seamlessly integrate into the context of their land, as well as their thoughtful consideration for future generations, demonstrated through the enduring structures built to withstand the test of time.

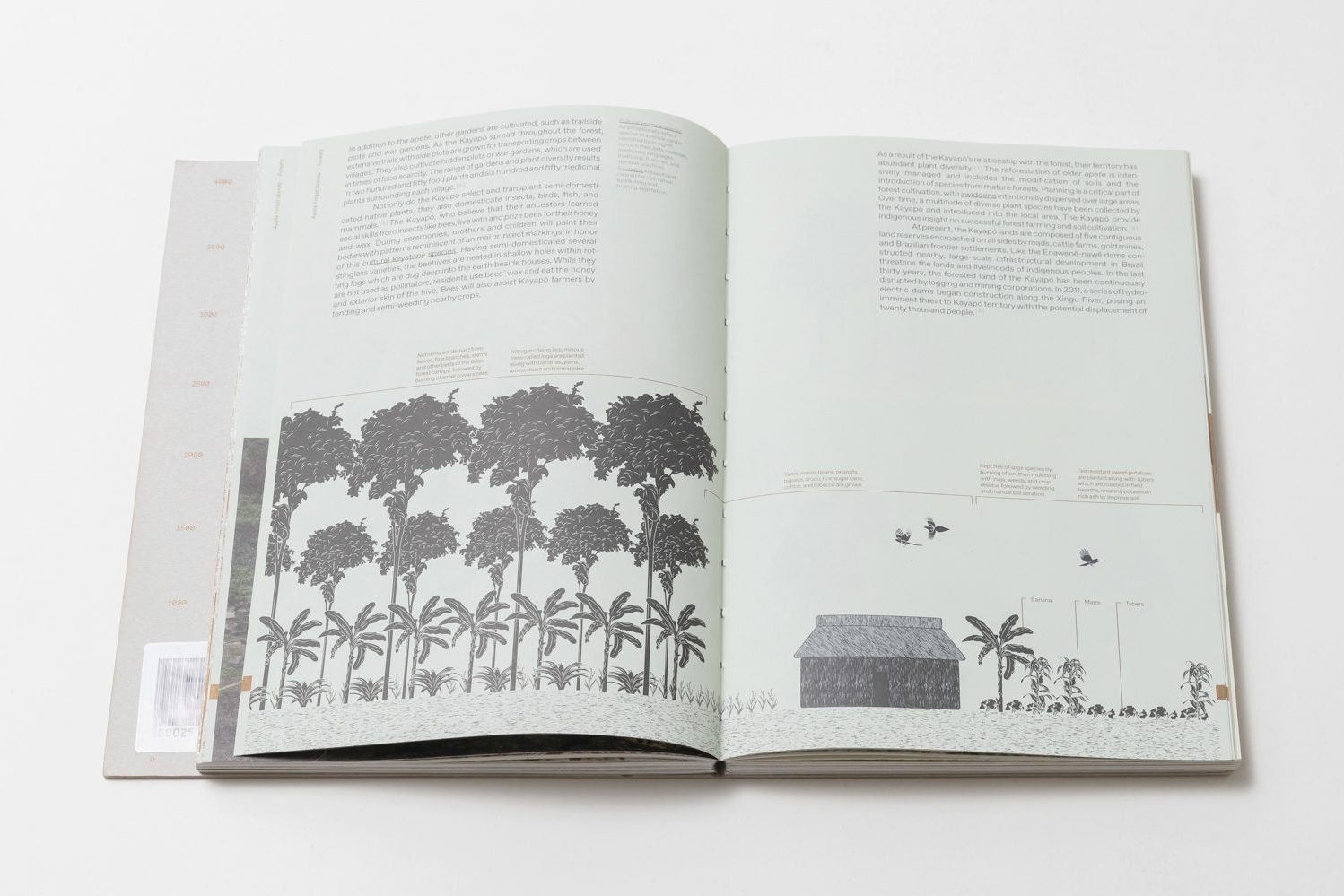

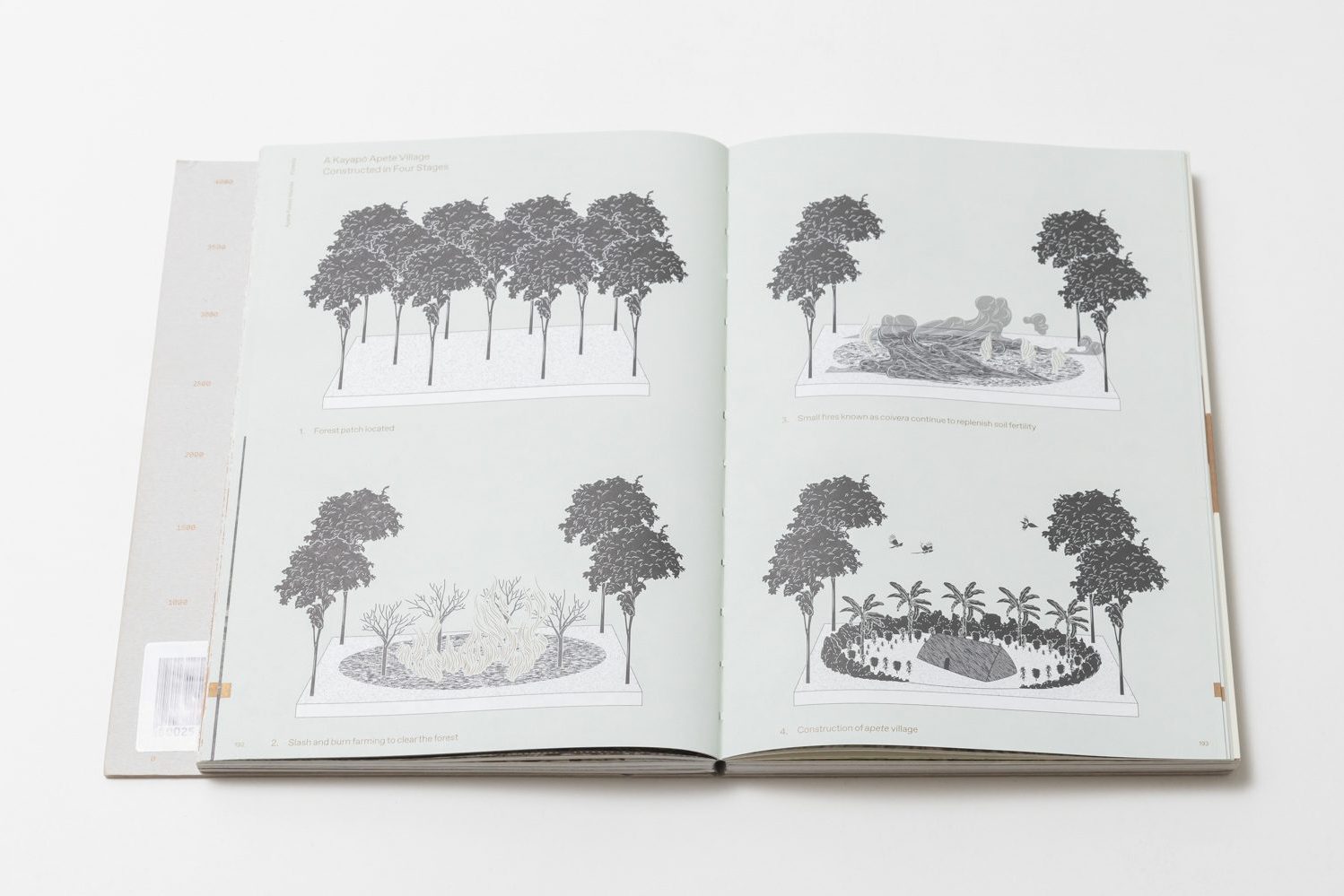

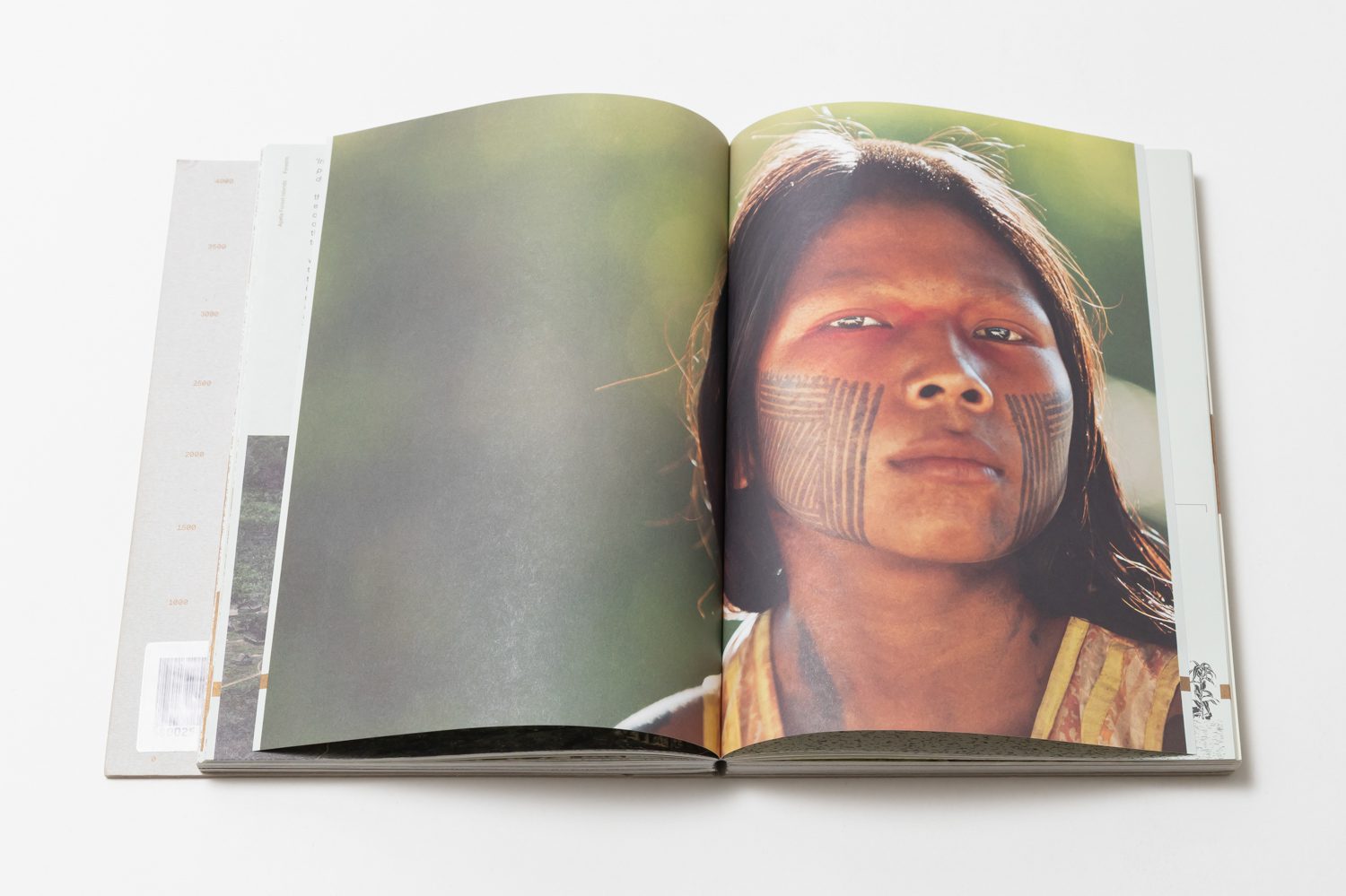

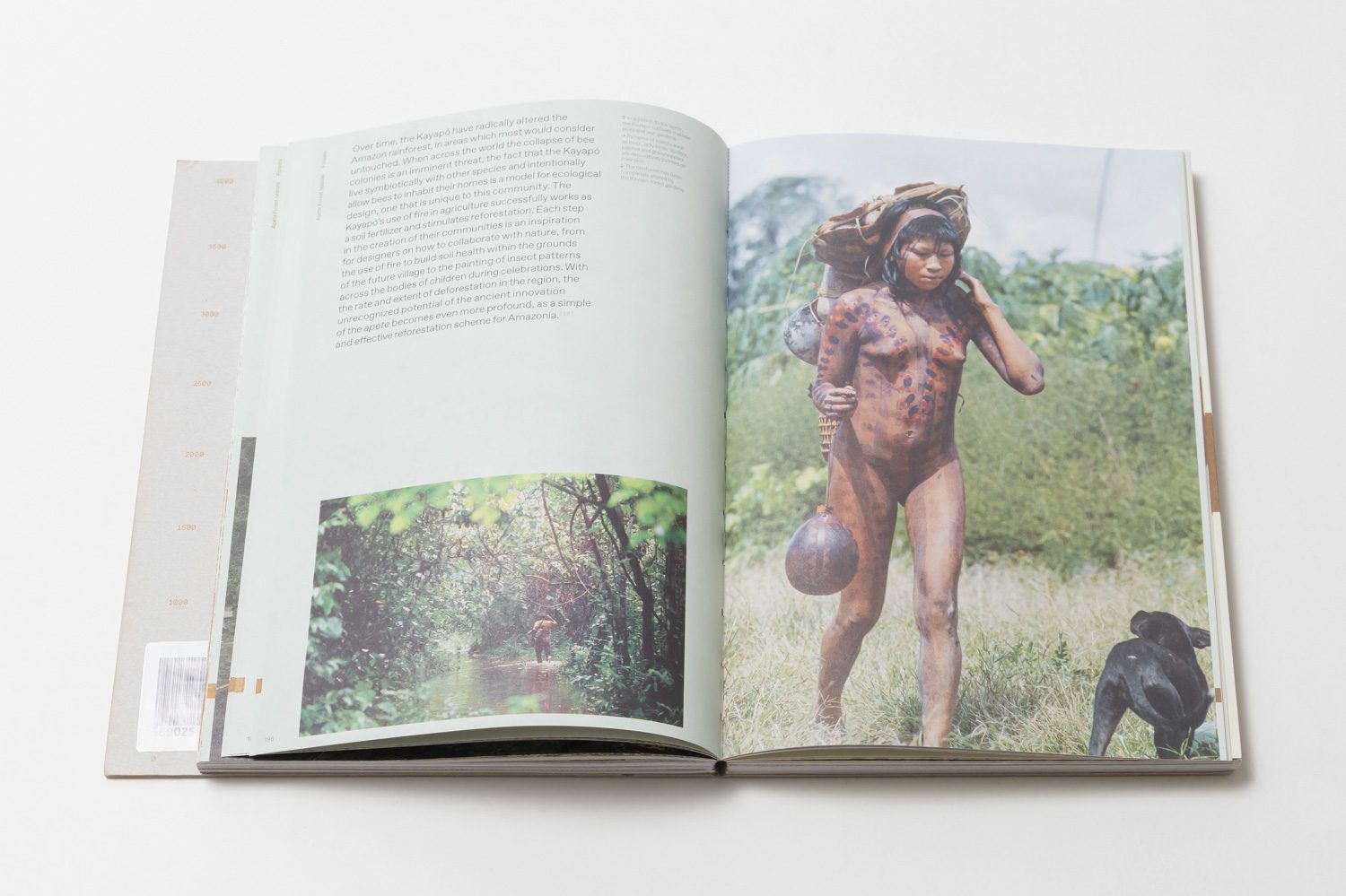

Beyond geography and climate, another intriguing aspect of studying technology and land use in a culture of this nature is the examination of ‘Cultural Keystone Species.’ These are living organisms, whether plants or animals, that share a profound relationship with any given subculture in every dimension of life. For instance, the Kayapo people in the Amazon rainforest exhibit a deep connection with insects, particularly bees, rooted in the belief that their ancestors acquired social skills from these little creatures. During important rituals and ceremonies, children and women of the Kayapo tribe paint their bodies with intricate black patterns resembling those of bees. This symbolic practice reinforces the Kayapo’s relationship with bees and is further reflected in the design of their villages, known as ‘Apete,’ whose circular layout is made up of strategically planted agricultural plots. The Kayapo people also deliberately bury hollow trunks near their homes to provide shelter for bees or stingless bees. This placement allows the bees to build their hives and produce honey, both of which are later collected and consumed as food. Simultaneously, the bees play a vital role in caretaking and propagating agricultural crops such as bananas and corn.

Julia underscores the impact of human activities on the environment, going beyond simple acts of creation or destruction. This encompasses the current paradigm of ecological preservation, wherein the demarcation of conservation zones frequently leads to the displacement of indigenous communities from their ancestral lands—many of which have been inhabited by these tribes for centuries (although the term ‘Anthropocene’ signifies the era where humans wield substantial influence over nature, it doesn’t necessarily connote that all human-nature relationships are inherently detrimental). Some of these relationships involve humans as integral components essential for the holistic functioning of the ecosystem.

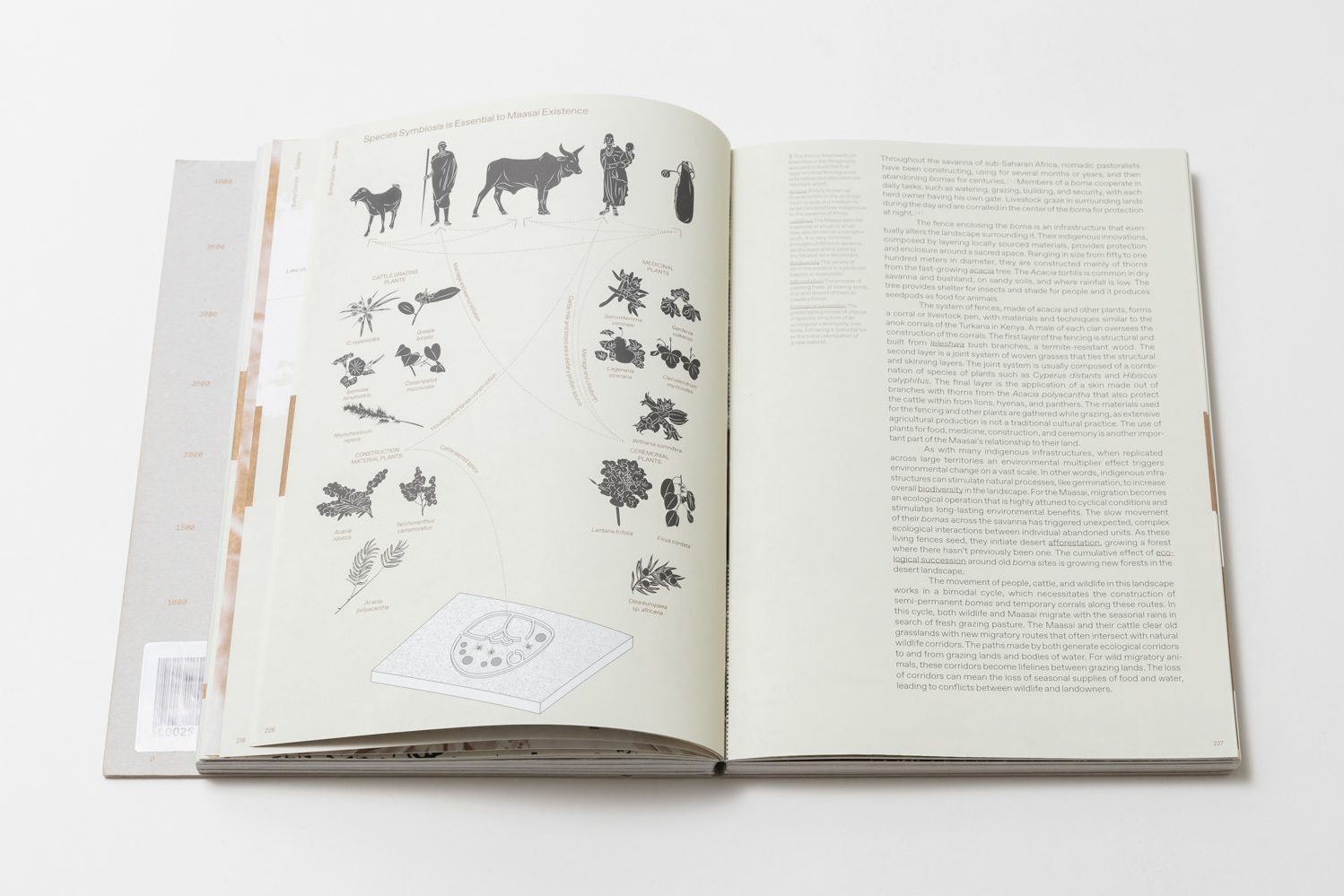

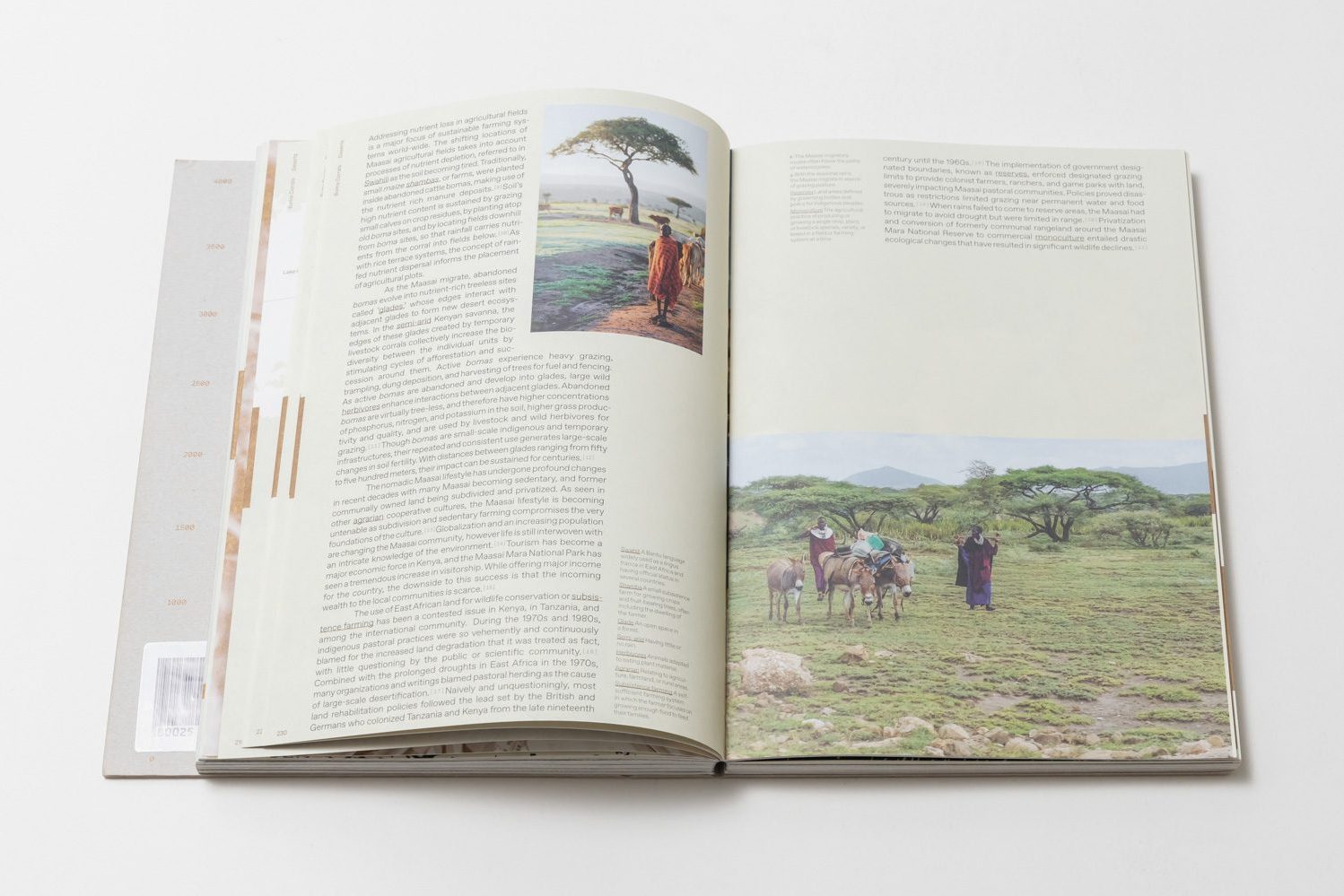

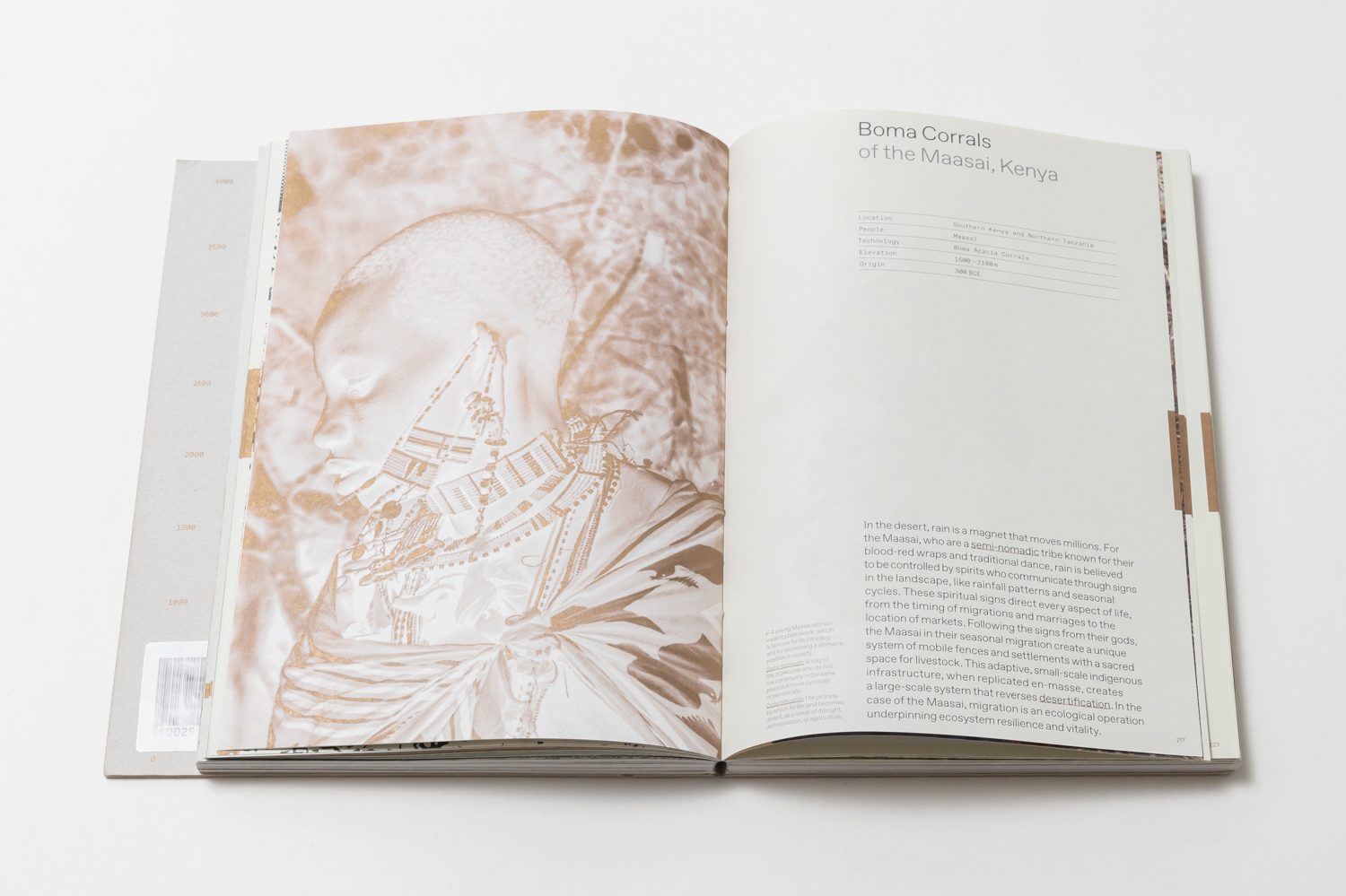

For instance, the Maasai people in the Kenyan plains around Mount Kilimanjaro annually relocate to establish semi-permanent shelters called ‘boma,’ constructed using thorny branches and rattan, serving as protective barriers for habitation. When the Maasai people move to new settlements during the dry season, the abandoned living areas transform into food sources for herbivores in the region. This, in turn, triggers a chain reaction leading to reforestation due to seeds animals disperse after their food consumption. The Maasai’s nomadic lifestyle, seeking more fertile lands during droughts, inadvertently contributes to the creation of wildlife corridors that connect different fertile regions. It turns out that separating humans from nature may eliminate significant possibilities for coexistence between humanity and the environment.

The book emphasizes the crucial role that designers play in shaping new cultures and narratives. Indigenous knowledge from the past can be a key for modern-day designers to use for crafting contemporary designs that do not resort to ‘greenwashing’ as a mere marketing tool. Furthermore, Julia advocates for a shift in the current design philosophy away from Charles Darwin’s ‘survival of the fittest’ and towards ‘survival of the most symbiotic.’

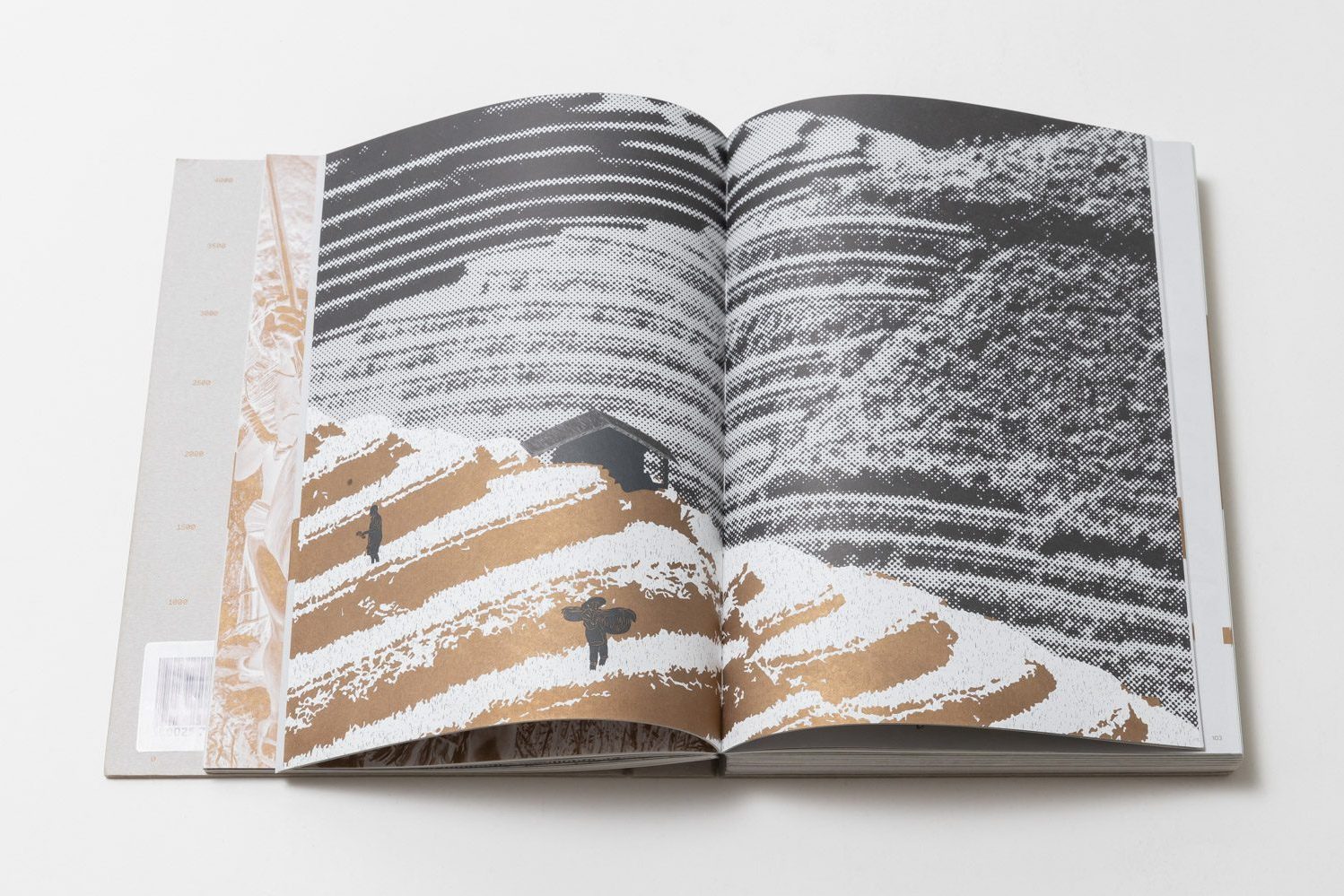

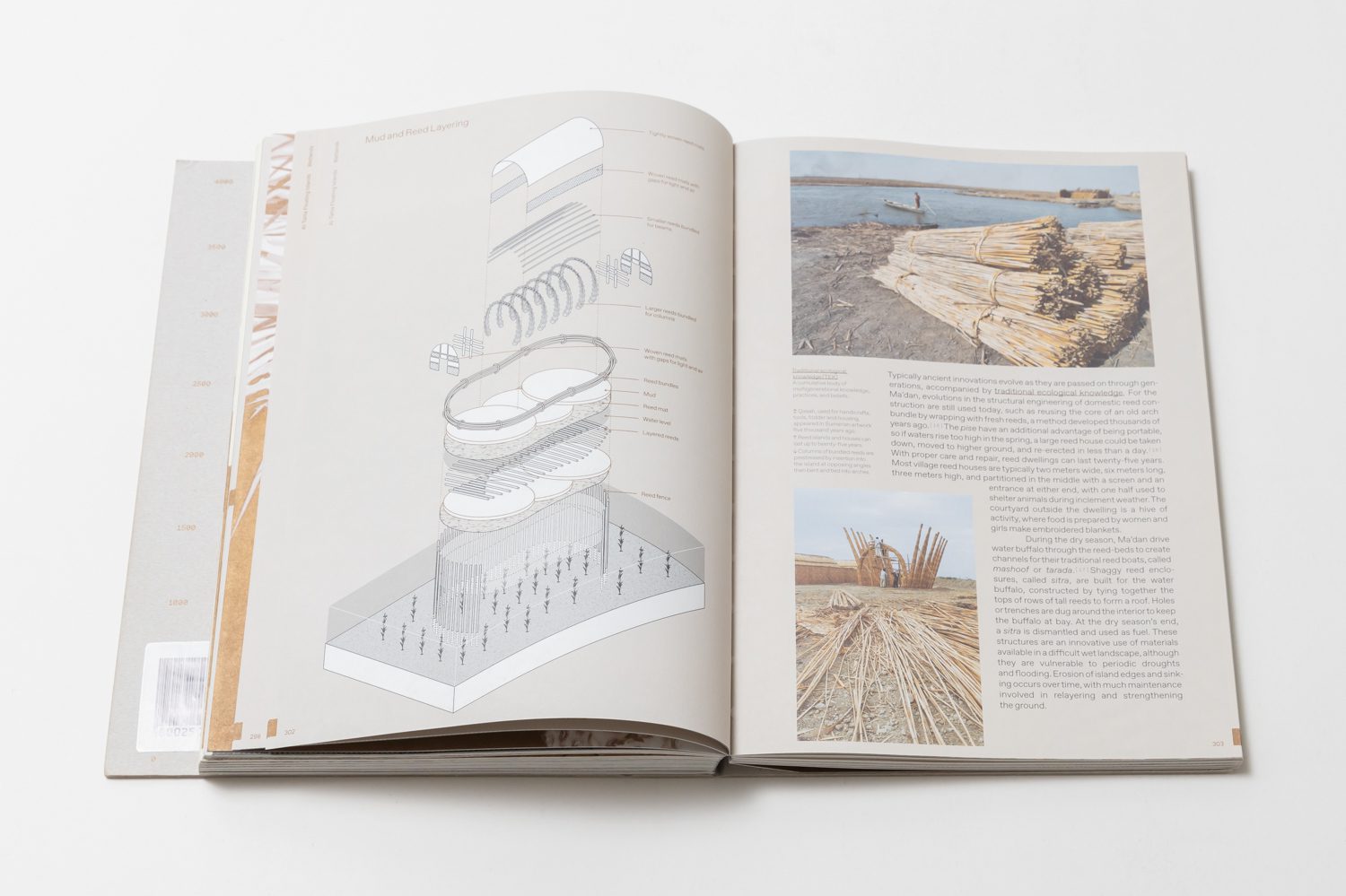

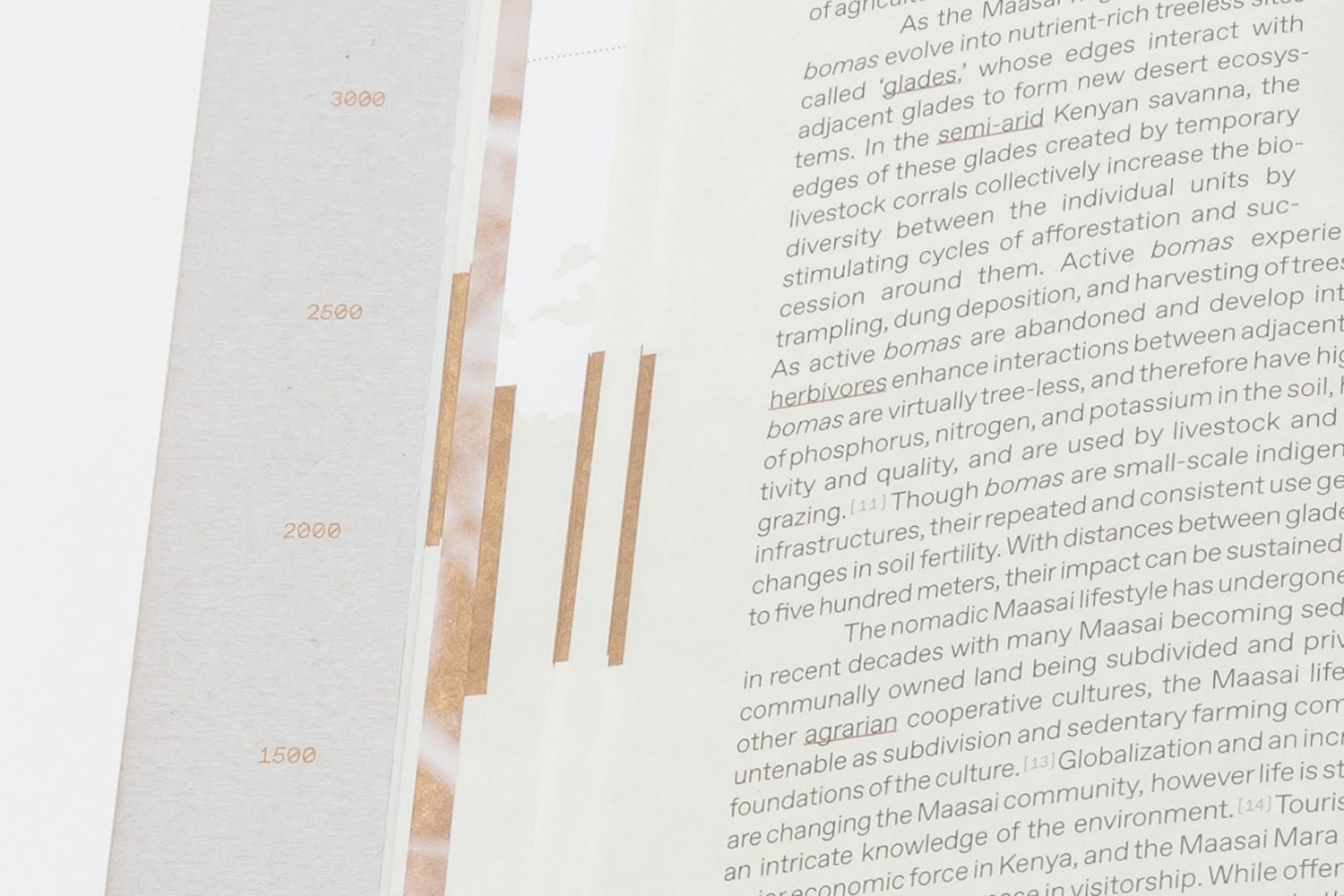

A noteworthy feature contributing to the book’s compelling storytelling is the physical design of the book itself, for which W-E Studio from New York is responsible for graphic design and art direction. Berke Yazicioglu, an illustrator from London, was enlisted to create all the illustrations in the book, ensuring that the content remains easily understandable despite its voluminous and complex nature, spanning over 400 pages. Various distinctive points, particularly in anthropology, geography, and biology, are conveyed to make the content more accessible to non-experts through simplified representations such as drawings, diagrams, isometrics, and illustrations that complement documentary-style photographs used as the primary narrative method in the book. Furthermore, small details, like the color strips on every page, can be utilized with the ruler on the inside cover to determine the sea level, which allows readers to get a better picture of the specific location of the tribe whose story is being read. These multifaceted characteristics elevate the book beyond its role as a textbook for academic references, due to its aesthetic qualities that are equivalent to an impressively well-crafted art book.

Before delving into the concluding section and summarizing the content of the book, let’s take a moment to contemplate and reflect on the human journey, observing how we have gradually distanced ourselves from nature throughout history. It began in the Age of Enlightenment, which prioritized scientific reasoning and individualism over traditional beliefs and practices. This trend continued with the Industrial Age where production was the priority, until reaching the current Digital Age. Despite the course of human history, what Julia suggests is not about completely discarding the mythologies that centralize technology, but rather revisiting and reconsidering the potential of indigenous innovations and knowledge from the past as usable technology. What is worrisome is not just the environmental impact currently unfolding but also the fact that we are gradually allowing the body of knowledge that humans have developed to deal with nature to slip away, relegating it to the realm of spirituality rather than practicality.

“Will we crumble or flourish?” The answer to our future lies in the paths we choose today. Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism by Julia Watson encourages us to reconsider sustainability, emphasizing that it has never been merely a contemporary issue but a timeless concern. The repercussions we face today are etched by the imprints of our past actions. The yet-to-unfold future teeters on how we reconnect with the forgotten wisdom and narratives of bygone eras. These reflections beckon us to ponder ‘humanity’ in its entirety—a term that transcends individualistic boundaries, encompassing not just one but various tribes and their collective legacies. While today’s environmental concerns act as a catalyst for corrective actions, the ensuing processes and results might unfold over a timespan beyond our present lifetimes.

Though seemingly regrettable, delving into the narratives of the past offers us a profound perspective. The Iroquois, Native Americans in the United States, adhered to the philosophy of judicious resource use, considering what would remain for their descendants for the next seven generations. It’s just like the living rubber fig tree bridges of the Khasi people in India where those who built them might not have had the chance to actually use them due to the building process lasting over half a century. While we cannot choose the kind of world we have to live in, we can create the world our descendants will inherit.

The opening words of this book serve as a declaration to the world we are passing on.

“This book is dedicated to the next seven generations.”